In part 1 of this series on trees and wood, I found examples of their being used for practical purposes in Homer and Hesiod, and a more detailed analysis by Theophrastus and others in part 2.

I also found that Homer and Hesiod also include references to myths, rituals, and sacred spaces associated with trees and wood, including nymphs, so for part 3, this current post, I looked for further examples in other sources.

The pine or fir

The pine or fir tree is associated with violence in one of the myths about Theseus—in this case being torn asunder:

{2.1.4} At the beginning of the Isthmus is the place where the brigand Sinis used to take hold of pine trees [pitus] and draw them down. All those whom he overcame in fight he used to tie to the trees [dendron], and then allow them to swing up again. Thereupon each of the pines [pitus] used to drag to itself the bound man, and as the bond gave way in neither direction but was stretched equally in both, he was torn in two. This was the way in which Sinis himself was slain by Theseus.

Pausanias Description of Greece 2.1.4, adapted from translation by Jones

Before Pentheus was discovered his viewing point was a pine or fir tree according to Euripides. Perhaps coincidentally his fate at the hands of the Maenads was also being torn apart:

Pentheus, that unhappy man, said, not seeing the crowd of women: “xenos , 1060 from where we are standing I cannot see these false Maenads. But on the banks of the ravine, ascending a lofty pine [elatē], I might view properly the shameful acts of the Maenads.” And then I saw the xenos perform a marvel. Seizing hold of the lofty top-most branch [klados] of a pine tree [elatē], 1065 he drew it down, down, down to the black ground. It was bent just as a bow or a curved wheel, when it is marked out by a compass, describes a circular course; in this way the xenos drew the mountain bough [klōn] and bent it to the earth, doing what no mortal could. 1070 He sat Pentheus down on the pine [elatinos] branch [ozos], and released it gently from his hands, taking care not to shake him off. …. . 1095 When they [the Maenads] saw my master sitting in the pine [elatē], first they climbed a rock towering opposite the tree and began to hurl at him large rocks violently thrown. At the same time he was fired upon by branches [ozos] of fir [elatinos], and other women hurled their thyrsoi through the air 1100 at Pentheus, a sad target indeed. … … . 1105 When they did not succeed in their toils, Agaue said: “Come, standing round in a circle, seize each a branch [ptorthos], Maenads, so that we may catch this inaccessible beast, and so that he does not make public the secret khoroi of the god.” They applied countless hands 1110 to the pine [elatē] and dragged it up from the earth. Pentheus falls crashing to the ground from his lofty seat, wailing greatly; for he knew he was near doom.

Euripides Bacchae 1058–1073, 1095–1100, 1105–1113, adapted from Sourcebook

Because of this, the tree was then used to make images:

They say that Pentheus treated Dionysus despitefully, his crowning outrage being that he went to Kithairon, to spy upon the women, and climbing up a tree [dendron] beheld what was done. When the women detected Pentheus, they immediately dragged him down, and joined in tearing him, living as he was, limb from limb. Afterwards, as the Corinthians say, the Pythian priestess commanded them by an oracle to discover that tree [dendron] and to worship it equally with the god. For this reason they have made these images from the tree.

Pausanias Description of Greece 2.2.7, adapted from translation by Jones

The oak: Dodona and elsewhere

Herodotus tells us one version of how the oak became associated with Dodona and the oracle of Zeus:

… the prophetesses of Dodona say: that two black doves had come flying from Thebes in Egypt, one to Libya and one to Dodona; [2] the latter settled on an oak tree [phēgos], and there uttered human speech, declaring that a place of divination from Zeus must be made there; the people of Dodona understood that the message was divine, and therefore established the oracular shrine. [3] … Such was the story told by the Dodonaean priestesses…; and the rest of the servants of the temple at Dodona similarly held it true.

Herodotus The Histories 2.55, adapted from translation by Godley

That oak itself carries an association with sentience:

And the harbor of Pagasai cried out terribly, and Pelian Argo herself, urging them to set forth. For in her had been driven a divine beam [doru], which Athena had fitted in the middle of the cutwater, of Dodonian oak [phēgos].

Apollonius of Rhodes Argonautica 1.524–527, adapted from translation by Seaton

Oaks elsewhere apparently had other properties, such as that noted by Pausanias in the district of Megalopolis where there is a spring on Mount Lykaios:

Should a drought persist for a long time, and the seeds in the earth and the trees wither, then the priest of Zeus Lykaios, after praying towards the water and making the usual sacrifices, lowers an oak [drûs] branch [kládos] to the surface of the spring, not letting it sink deep. When the water has been stirred up there rises a vapor, like mist; after a time the mist becomes cloud, gathers to itself other clouds, and makes rain fall on the land of the Arcadians.

Pausanias Description of Greece 8.38.4, adapted from translation by Jones

Pausanias says that the oak at Dodona was one of the oldest in Greece, and mentions other ancient trees at sacred sites:

If I am to base my calculations on the accounts of the Greeks in fixing the relative ages of such trees [dendron] as are still preserved and flourish, the oldest of them is the withy [lugos] growing in the Samian sanctuary of Hērā, after which come the oak [drûs] in Dodona, the olive [elaia] on the Acropolis and [the olive] in Delos. The third place in respect of age the Syrians would assign to the bay tree [daphnē] they have in their country. Of the others this plane tree [platanos] is the oldest.

Pausanias Description of Greece 8.23.5, adapted from translation by Jones

Delos: the palm and the olive

I was surprised to see Pausanias mention an olive in Delos, because I had otherwise associated the palm tree with that site, because of Leto’s giving birth to Apollo and Artemis there. The story is told in the Homeric Hymns, and also in Callimachus (where the focus is mainly on Apollo):

And she loosed her girdle and leaned back her shoulders against the trunk of a palm-tree [phoînix], oppressed by the grievous distress, and the sweat poured over her flesh like rain. And she spoke in her weakness: “Why, child, do you weigh down your mother? There, dear child, is your island floating on the sea. Be born, be born, my child, and gently issue from the womb.”

Callimachus Hymn IV to Delos208–214,adapted from translation by Mair

However, Callimachus also provides a reference to the olive tree:

In that hour, O Delos, all your foundations became of gold: with gold your round lake flowed all day, and your natal olive-tree [elaía] put forth a golden shoot [ernos], and with gold flowed coiled Inopus in deep flood.

Callimachus Hymn IV to Delos 260–264, adapted from translation by Mair)

In the footnote to his translation of this section, Mair provides information from the scholia:

“In Delos it was the custom to run round the altar of Apollo and to beat the altar and, their hands tied behind their backs, to take a bite from the olive-tree.” (schol.).”

So this suggests the olive was important in Delos, but quite what that particular custom signified is not clear!

Olive trees of all kinds

Olive trees are sacred in other places, most famously in Athens; Apollodorus provides an account of how this came about during the reign of the first king, Kekrops:

In his time, they say, the gods resolved to take possession of cities in which each of them should receive his own peculiar worship. So Poseidon was the first that came to Attica, and with a blow of his trident on the middle of the acropolis, he produced a sea which they now call Erekhtheis. After him came Athena, and, having called on Kekrops to witness her act of taking possession, she planted [phuteúein] an olive tree [elaia], which is still shown in the Pandrosium. But when the two strove for possession of the country, Zeus parted them and appointed arbiters, not, as some have affirmed, Kekrops and Kranaos, nor yet Erysikhthon, but the twelve gods. And in accordance with their verdict the country was adjudged to Athena, because Kekrops bore witness that she had been the first to plant [phuteúein] the olive [elaia]. Athena, therefore, called the city Athens after herself, and Poseidon in hot anger flooded the Thriasian plain and laid Attica under the sea.

Apollodorus Library 3.14.1, adapted from translation by Frazer

But olive trees also associated with other myths, for example in these stories about Herakles and Hippolytus:

As you go up to Mount Coryphum you see by the road an olive [elaia] tree [phuton] called Twisted. It was Herakles who gave it this shape by bending it round with his hand, but I cannot say whether he set it to be a boundary mark against the Asinaeans in Argolis, since in no land, which has been depopulated, is it easy to discover the truth about the boundaries. (2.28.2)

Here [= Troizen] there is also a Hermes called Polygius. Against this statue, they say, Herakles leaned his club. Now this club, which was of wild olive [kotinos], taking root [emphuein] in the earth (if anyone cares to believe the story), grew up [anablastanein] again and is still alive; Hēraklēs, they say, discovering the wild olive [kotinos] by the Saronic Sea, cut [temeîn] a club from it. (2.31.10)

Hēraklēs, being the eldest, matched his brothers, as a game, in a running race, and garlanded the winner with a branch of wild olive, of which they had such a copious supply that they slept on heaps of its leaves while still green. It is said to have been introduced into Greece by Hēraklēs from the land of the Hyperboreans, men living beyond the home of the North Wind. (5.7.7)

As you make your way to the Psiphaean Sea you see a wild olive growing, which they call the Bent Rhakhos. The Troizenians call rhakhos every kind of barren [akarpos] olive [elaia]—kotinos, phulia, or elaios—and this tree they call Bent because it was when the reins caught in it that the chariot of Hippolytus was upset. (2.32.10)

Pausanias Description of Greece 2.28.2, 2.31.10, 5.7.7, 2.32.10, adapted from translation by Jones

Hera and the withy

The oldest tree that Pausanias mentioned in 8.23.5 (quoted above) was the withy, which he also mentions in his account of the sanctuary:

Some say that the sanctuary of Hērā in Samos was established by those who sailed in the Argo, and that these brought the image from Argos. But the Samians themselves hold that the goddess was born in the island by the side of the river Imbrasos under the withy [lugos] that even in my time grew in the Heraion.

Pausanias Description of Greece 7.4.4, adapted from translation by Jones

So again, as in Delos, a tree is associated with the birth of a god.

Another story associating Samos, Hera, and the withy is told in the Deipnosophists where the author has Demokritos quoting Menodotos of Samos:

Admete, the wife of Eurystheus, after she had fled from Argos, came to Samos, and there, when a vision of Hera had appeared to her, she wishing to give the goddess a reward because she had arrived in Samos from her own home in safety, undertook the care of the temple…. But the Argives hearing of this, and being indignant at it, persuaded the Tyrrhenians by a promise of money, to employ piratical force and to carry off the statue,—the Argives believing that if this were done Admete would be treated with every possible severity by the inhabitants of Samos. Accordingly the Tyrrhenians came to the port of Hera, and having disembarked, immediately applied themselves to the performance of their undertaking. And as the temple was at that time without any doors, they quickly carried off the statue, and bore it down to the seaside, and put it on board their vessel. And when they had loosed their cables and weighed anchor, they rowed as fast as they could, but were unable to make any progress. And then, thinking that this was owing to divine interposition, they took the statue out of the ship again and put it on the shore; and having made some sacrificial cakes, and offered them to it, they departed in great fear. But when, the first thing in the morning, Admete gave notice that the statue had disappeared, and a search was made for it, those who were seeking it found it on the shore. And they, like Carian barbarians, as they were, thinking that the statue had run away of its own accord, bound it to a fence made of osiers [lugos], and took all the longest branches [klados] on each side and twined them round the body of the statue, so as to envelop it all round. But Admete released the statue from these bonds, and purified it, and placed it again on its pedestal, as it had stood before. And on this account once every year, since that time, the statue is carried down to the shore and hidden, and cakes are offered to it: and the festival is called τονεὺς [toneus], because it happened that the statue was bound tightly (συντόνως [suntonōs]) by those who made the first search for it.

Athenaeus The Deipnosophists 15.12, adapted from translation by Yonge

Apollo and Daphne: the laurel

The laurel [daphnē] is connected with Apollo and the story of Daphne, which is recounted in various ancient sources:

I pass over the story current among the Syrians who live on the river Orontes, and give the account of the Arcadians and Eleians. Oinomaos, prince of Pisa, had a son Leukippos. Leukippos fell in love with Daphne, but despaired of winning her to be his wife by an open courtship, as she avoided all the male sex. The following trick occurred to him by which to get her. Leukippos was growing his hair long for the river Alpheios.

Braiding his hair as though he were a maiden, and putting on woman’s clothes, he came to Daphne and said that he was a daughter of Oinomaos, and would like to share her hunting. As he was thought to be a maiden, surpassed the other girls in nobility of birth and skill in hunting, and was besides most assiduous in his attentions, he drew Daphne into a deep friendship.

The poets who sing of Apollo’s love for Daphne make an addition to the tale; that Apollo became jealous of Leukippos because of his success in his love. Forthwith Daphne and the other girl conceived a longing to swim in the Ladon, and stripped Leukippos in spite of his reluctance. Then, seeing that he was not a girl, they killed him with their javelins and daggers.Pausanias Description of Greece 8.20.2–4, adapted from translation by Jones

I wonder what the Syrian version was!

Another version is told by Parthenius:

This is how the story of Daphne, the daughter of Amyklas, is related. She used never to come down into the town, nor consort with the other maidens; but she got together a large pack of hounds and used to hunt, either in Laconia, or sometimes going into the further mountains of the Peloponnese. For this reason she was very dear to Artemis, who gave her the gift of shooting straight. On one occasion she was traversing the country of Elis, and there Leukippos , the son of Oinomaos, fell in love with her; he resolved not to woo her in any common way, but assumed women’s clothes, and, in the guise of a maiden, joined her hunt. And it so happened that she very soon became extremely fond of him, nor would she let him quit her side, embracing him and clinging to him at all times. But Apollo was also fired with love for the girl, and it was with feelings of anger and jealousy that he saw Leukippos always with her; he therefore put it into her mind to visit a stream with her attendant maidens, and there to bathe. On their arrival there, they all began to strip; and when they saw that Leukippos was unwilling to follow their example, they tore his clothes from him: but when they thus became aware of the deceit he had practiced and the plot he had devised against them, they all plunged their spears into his body. He, by the will of the gods, disappeared; but Daphne, seeing Apollon advancing upon her, took vigorously to flight; then, as he pursued her, she implored Zeus that she might be translated away from mortal sight, and she is supposed to have become the tree [dendron] which is called bay [daphnē] after her.

Parthenius Love Romances 15: The Story of Daphne, adapted from translation by Gaselee

Garlands and crowns

Pausanias tells us:

The reason why a crown of laurel [daphnē] is the prize for a Pythian victory is in my opinion simply and solely because the prevailing tradition has it that Apollon fell in love with the daughter of Ladon [i.e. Daphne].

Pausanias Description of Greece 10.7.8, adapted from translation by Jones

The wild olive was associated with a prize garland for athletic contests in Elis. Once again we see a connection between Herakles and this tree:

Herakles, being the eldest, matched his brothers, as a game, in a running race, and garlanded the winner with a branch [klados] of wild olive [kotinos]: they had such a copious supply of wild-olive [kotinos] that they slept on heaps of its leaves [phullon] while still green [khlōros]. It is said to have been introduced into Greece by Hēraklēs from the land of the Hyperboreans, men living beyond the home of the North Wind.

Pausanias Description of Greece 5.7.7, adapted from translation by Jones

Pausanias also mentions that different garlands are used in other places:

The reason why at Olympia the victor receives a garland of wild-olive [kotinos] I have already explained in my account of Elis; [= Pausanias 5.7.7] … At the Isthmus the pine [pitus], and at Nemea celery [selinon] became the prize to commemorate the sufferings of Palaimon and Arkhemoros. At most games, however, is given a garland of palm [phoînix], and at all a palm [phoînix] is placed in the right hand of the victor.

The origin of the custom is said to be that Theseus, on his return from Crete, held games in Delos in honor of Apollo, and garlanded the victors with palm [phoînix]. Such, it is said, was the origin of the custom.

Pausanias Description of Greece 8.48.2–3, adapted from translation by Jones

Plutarch, in Moralia: Quaestiones Conviviales recounts a discussion about the palm as an honor in the games.

Herodes … added that he could not tell the reason why, since each of the games gave a particular garland, yet all of them bestowed the palm [phoînix].

Plutarch Quaestiones Conviviales 8.4, adapted from translation by Goodwin

Here are some of the reasons suggested during the conversation:

“Therefore,” said Sospis, “let every one carefully give his sentiments of the matter in hand. I begin, and think that, as far as possible, the honor of the victor should remain fresh and immortal. Now a palm-tree [phoînix] is the longest lived of any … And this almost alone enjoys the privilege (though it is said to belong to many beside) of having always fresh and the same leaves [phullon]. For neither the laurel [daphnē] nor the olive [elaia] nor the myrtle [mursinē], nor any other of those trees called non-leaf-shedding [phullorroeîn], is always seen with the very same leaves [phullon]; but as the old fall, new ones grow. …. But the palm [phoînix], never shedding leaves it has put forth [phúein], is continually evergreen [aeiphullos]. And this power of this [tree], I believe, men think agreeable to, and fit to represent, the strength of victory.”

When Sospis had done, Protogenes the grammarian, calling Praxiteles the commentator by his name, said: “….Lately, I remember, reading in the Attic annals, I found that Theseus first instituted games in Delos, and tore off a branch[klados] from the sacred palm-tree [phoînix]… “

And Praxiteles said: “This is uncertain; but perhaps some will demand of Theseus himself, upon what account, when he instituted the game, he broke off a branch [klados] of palm [phoînix] rather than of laurel [daphnē] or of olive [elaia]. But consider whether this be not a prize proper to the Pythian games, as belonging to Amphictyon. For there they first, in honor of the god, crowned the victors with laurel [daphnē] and palm [phoînix], as consecrating to the god, not the laurel [daphnē] or olive [elaia], but the palm [phoînix]. So Nikias did, who defrayed the charges of the solemnity in the name of the Athenians at Delos; the Athenians themselves at Delphi; and before these, Kupselos the Corinthian. For this god is a lover of games, and delights in contending for the prize at harping, singing, and throwing the bar, and, as some say, at cuffing; and assists men when contending…”

Plutarch Quaestiones Conviviales 8.4, adapted from translation by Goodwin

Whatever they might say about the symbolic properties of the tree, there could also be, as with Pausanias’ examples, a mythological aetiology!

Tree nymphs: hamadryads

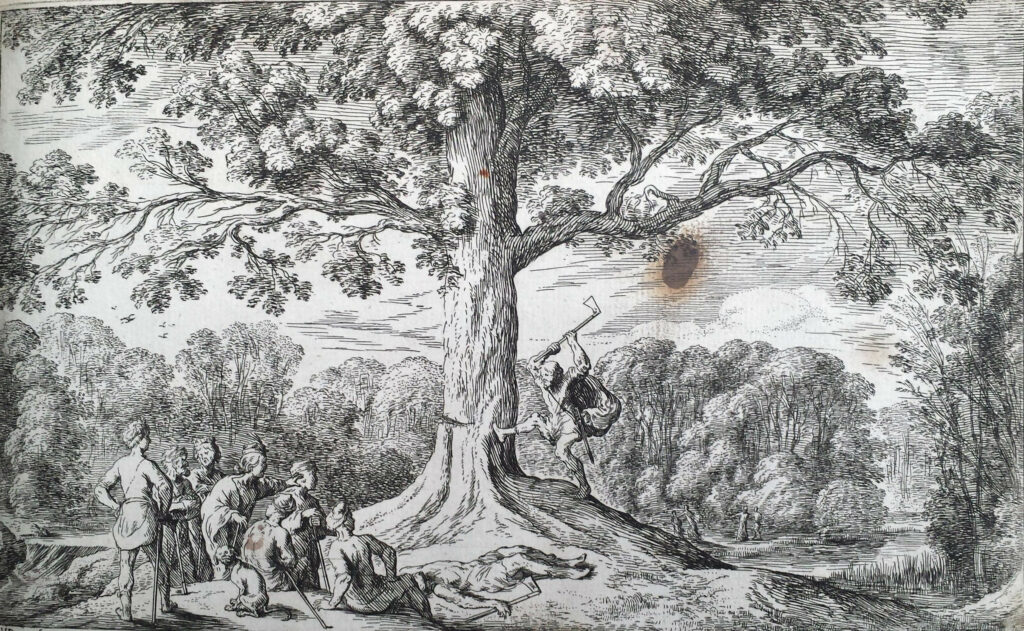

© The Trustees of the British Museum

If Daphne was a young woman who was turned into a tree, there are nymphs who live in or are trees: we met some of them in part 1. The Meliai were ash-nymphs and there were others, including those known as Dryads and Hamadryads.

We read a story about one in last month’s Book Club in Callimachus:

[24] Not yet in the land of Cnidus, but still in holy Dotion dwelt the Pelasgians and they made for themselves a fair grove [alsos] abounding in trees [dendron]; hardly would an arrow have passed through them. Therein was pine [pitus], and therein were mighty elms [ptelea], and therein were pear-trees [okhnē], and therein were fair sweet-apples [gluku-malon]; and from the ditches gushes up water as it were of amber. And the goddess loved the place to madness, even as Eleusis, as Triopum, as Enna.

[31] But when their favoring divinity became wroth with the Triopidai, then the worse counsel took hold of Erysikhthon. He hastened with twenty attendants, all in their prime, all men-giants able to lift a whole city, arming them both with double axes [pelekus] and with hatchets [axinē], and they rushed shameless into the grove [alsos] of Demeter. Now there was a poplar [aigeiros], a great tree [dendreon] reaching to the sky, and thereby the nymphs were wont to sport at noontide. This [poplar] was smitten first and cried a woeful cry to the others. Demeter marked that her holy tree [xulon] was in pain, and she as angered and said: “Who cuts down [koptein] my fair tree [dendreon]?” Straightway she likened her to Nikippe, whom the city had appointed to be her public priestess, and in her hand she grasped her fillets and her poppy [mēkōn], and from her shoulder hung her key. And she spake to soothe the wicked and shameless man and said: “My child, you who cut down [koptein] the trees [dendreon] which are dedicated to the gods, stay, my child, child of thy parents’ many prayers, cease and turn back your attendants, lest the lady Demeter be angered, whose holy place you are plundering.”

[50] But … he said: “Give way, lest I fix my great ax [pelekus] in your flesh! These [trees] shall make my tight dwelling in which evermore I shall hold pleasing banquets enough for my companions.” So spoke the youth, and Nemesis recorded his evil speech. And Demeter was angered beyond telling and put on her goddess shape. Her steps touched the earth, but her head reached up to Olympus. And they, half-dead when they beheld the lady goddess, rushed suddenly away, leaving the bronze [axes] in the trees [drûs]. And she left the others alone – for they followed by constraint beneath their master’s hand – but she answered their angry king: “Yea, yea, build your house, dog, dog, that you are, in which you will hold festival; for frequent banquets shall be yours hereafter.” So much she said and devised evil things for Eryhthon.

[66] Straightway she sent on him a cruel and evil hunger – a hunger burning and strong – and he was tormented by a grievous disease. Wretched man, as much as he ate, so much did he desire again.

Callimachus Hymn VI to Demeter, adapted from translation by Mair

A similar story is told in Apollonius’ Argonautica, when Phineus recounts an incident concerning Paraibios’ father. A note by George W. Mooney to this passage in his 1912 Greek edition of Apollonius Rhodius Argonautica explains: “ἁμαδρυάδος: Hamadryades (ἅμα, δρῦς) were nymphs whose life was bound up in that of the tree with which they had come into being, and which was their home.”

For he when alone in the mountains, felling [temnein] trees [dendron], indeed at one time made light of the appeals of a hamadryad [Hamadruas] nymph, who, weeping, was imploring him with a vehement speech, not to cut down the stump [premnon] of the oak tree [drûs] of the same age as herself, in which for a long time she had been living continuously: but he in the arrogance of youth recklessly felled [tmēgein] it. Then the nymph made her death a curse, to him and to his children.

Apollonius of Rhodes Argonautica 2.476–483, adapted from translation by Seaton

These are just a few of the mythological stories and sacred associations of trees. I hope you will join me in the Forum to share others.

Selected vocabulary

Based on definitions in LSJ:

aeíphullos [ἀείφυλλος, ἀείφυλλον] adj. not deciduous, evergreen

aígeiros [αἴγειρος, αἰγείρου, ἡ] black poplar

akarpos [ἄκαρπος, ἄκαρπον] adj. without fruit, barren

álsos [ἄλσος, ἄλσεος, τό] grove, precinct

anablastánein [ἀναβλαστάνειν] to shoot up, put forth

áxinē [ἀξινη, ἀξίνης, ἡ] ax, ax-head

daphnē [δάφνη, δάφνης, ἡ] laurel, bay

déndron / déndreon [δένδρον/δένδρεον, δένδρου/δενδρέου, τό] tree

dóru [δόρυ, δόρατος, τό] stem, tree, plank

druás [δρυάς, δρυάδος, ἡ] dryad,

drûs [δρῦς, δρυός, ἡ ] tree, oak

elaía [ἐλαία, ἐλαίας, ἡ] olive-tree

elátē [ἐλάτη, ἐλάτης ἡ] silver fir, pine

elátinos [ἐλάτινος, -η, ον] adj. of fir, of pine

emphúein [ἐμφύειν] to implant, be rooted in

érnos [ἔρνος, ἔρνεος, τό] young sprout, shoot

glukúmalon [γλυκύμαλον, γλυκυμάλου, τό] sweet-apple

hamadruás [ἁμαδρυάς, ἁμαδρυάδος, ἡ] hamadryad,

khlōrós [χλωρός, χλωρά, χλωρόν] adj. greenish-yellow, pale green, fresh

kládos [κλάδος, κλάδου, ὁ] branch, shoot, plank

klōn [κλών, κλωνός, ὁ] twig

kóptein [κόπτειν] to cut, strike, fell

kótinos [κότινος, κοτίνου, ὁ, ἡ] wild olive-tree

lúgos [λύγος, λύγου, ἡ] withy, a willow-like tree, osier

mēkōn [μήκων, μήκωνος, ἡ ] poppy

mursínē [μυρσίνη, μυρσίνης, ἡ] myrtle

ókhnē [ὄχνη, ὄχνης, ἡ / ὄγχνη ] wild pear, pear-tree

ózos [ὄζος, ὄζου, ὁ] bough, branch, twig

pélekus [πέλεκυς. πέλεκεος/πέλεκεως, ἡ] ax, hatchet

phēgós [φηγός, φηγοῦ, ἡ] Valonia oak, Quercus Aegilops

phúein [φύειν] to bring forth, put forth leaves etc.

phulía [φυλία, ἡ] wild olive, but distinguished from kótinos

phúllon [φύλλον, φύλλου, τό] leaf, foliage

phullorroeîn [φυλλορροεῖν] to shed leaves

phuteúein [φυτεύειν] to plant

phutón [φυτόν, φυτοῦ, τό] plant, tree

pítus [πίτυς, πίτυος, ἡ] pine

plátanos [πλάτανος, πλατάνου, ἡ] plane-tree

phoînix [φοῖνιξ, φοίνικος, ὁ, ἡ,] date-palm, palm

prémnon [πρέμνον, πρέμνου, τό] bottom of the trunk of a tree, stump, stem, trunk

pteléa [πτελέα, πτελέας, ἡ] elm

ptórthos [πτόρθος, πτόρθου, ὁ] young branch, shoot, sucker, sapling

rhakhós [ῥαχός, ῥαχοῦ, ἡ] thorn-hedge, twig, branch; wild olive

sélinon [σέλινον, σελίνου, τό,] celery

témnein, temeîn [τέμνειν, τεμεῖν ] to cut

tmēgein [τμήγω] to cut, cleave

xúlon [ξύλον, ξύλου, τό] singular: piece of wood, log, beam, post; plural, wood cut and ready for use, firewood, timber

Related posts

Trees and wood | Part 1: Homer and Hesiod

Trees and wood | Part 2: Theophrastus on the uses of timber

Bibliography

Pausanias Description of Greece

English text: Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918.

Online at Perseus

Greek text: Pausaniae Graeciae Descriptio, 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903.

Online at Perseus

Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook: Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English. Gregory Nagy. 2013.

https://chs.harvard.edu/book/the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours-sourcebook/

Euripides Bacchae

English text: Translated by T. A. Buckley. Revised by Alex Sens. Further Revised by Gregory Nagy

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Euripides. Euripidis Fabulae, vol. 3. Gilbert Murray. Oxford. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1913.

Online at Perseus

Herodotus Histories

English and Greek text: Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

Apollonius of Rhodes Argonautica

English text: Apollonius Rhodius. Argonautica. Translated by Seaton, R. C. Loeb Classical Library Volume 001. London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1912.

Online at theoi.com

Greek text: Argonautica. Apollonius Rhodius. George W. Mooney. London. Longmans, Green. 1912.

Online at Perseus

Callimachus Hymns

English text: Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams. Lycophron. Aratus. Translated by Mair, A. W. & G. R. Loeb Classical Library Volume 129. London: William Heinemann, 1921.

Online at theoi.com

Greek text: Callimachus. Works. A.W. Mair. London: William Heinemann; New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons. 1921.

Online at Perseus

Apollodorus Library

English and Greek texts: Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer’s notes.

Online at Perseus

Athenaeus The Deipnosophists

English text: C.D. Yonge. Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists. Or Banquet Of The Learned Of Athenaeus. London. Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden. 1854.

Online at Perseus

Greek text: Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists. with an English Translation by. Charles Burton Gulick. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1927. 1.

Online at Perseus

Parthenius Love Romances

Longus, Daphnis and Chloe. Parthenius, Love Romances. Translated by Edmonds, J M and Gaselee, S. Loeb Classical Library Volume 69. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1916.

Online at theoi.com

Greek text: Parthenius. Erotici Scriptores Graeci, Vol 1. Rudolf Hercher. in aedibus B. G. Teubneri. Leipzig. 1858.

Online at Perseus

Plutarch Questiones Conviviales

English text: Plutarch’s Morals. Translated from the Greek by several hands. Corrected and revised by. William W. Goodwin, PH. D. Boston. Little, Brown, and Company. Cambridge. Press Of John Wilson and son. 1874. 3

Online at Perseus

Greek text: Plutarch. Moralia. Gregorius N. Bernardakis. Leipzig. Teubner. 1892. 4

Online at Perseus

LSJ: Liddell, Henry George, and Scott, Robert. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones, with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. 1940. Oxford. Clarendon Press.

Online at Perseus

Texts accessed September 2022

Image credits

Elpinikos Painter: Theseus and Sinis. Tondo of an Attic red-figure kylix, 490–480 BCE

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theseus_Sinis_Staatliche_Antikensammlungen_8771.jpg

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The building of the Argo: Athena on the left. Terracotta relief, Roman, c 1st century CE.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Building_Argo_BM_TerrD603.jpg

Photo: Jastrow. Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license, via Wikimedia Commons

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en

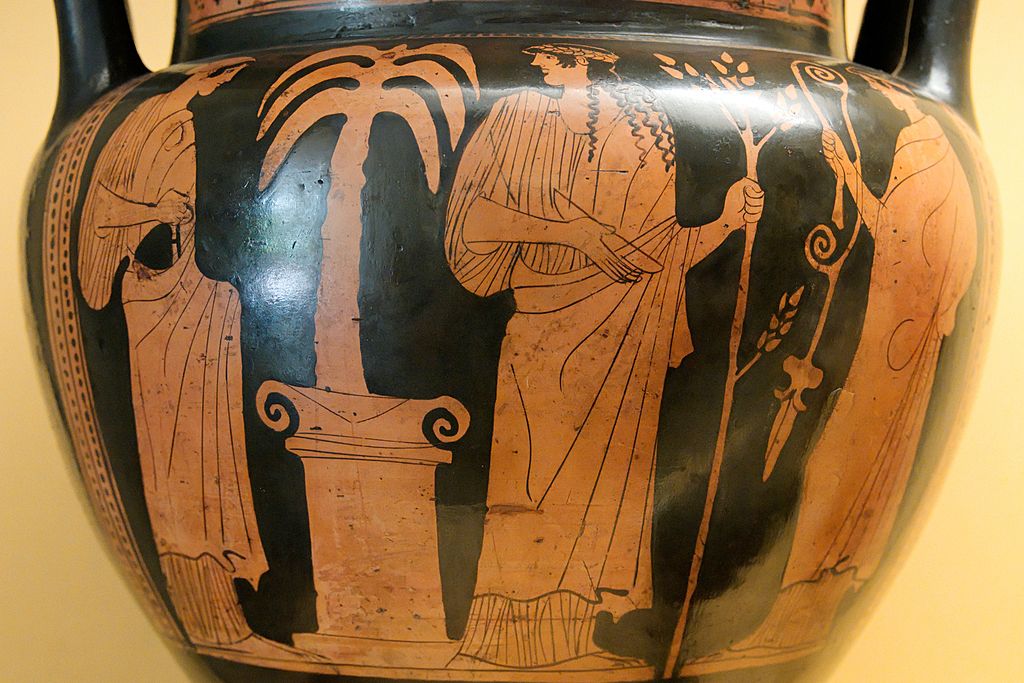

Comacchio Painter: Artemis and Apollo with palm tree. Attic red-figure column-krater, c 450 BCE.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Apollo_Artemis_Delos_MAN.jpg

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen (Jastrow), Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license, via Wikimedia Commons

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en

Olive tree on the Acropolis

Photo: Kosmos Society

Heraion of Samos

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heraion_of_Samos#/media/File:Heraion_of_Samos_2.jpg

Photo: Tomisti. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

Bernini: Apollo and Daphne

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Apollo_and_Daphne_(Bernini).jpg

Photo: Architas, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en

Acrobat Painter: youth handing over a victor’s wreath, late 4th century BCE

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hydria_athlete_Lucania,_Acrobat_Painter,_late_4th_c_BC,_Prague_Kinsky,_NM-HM10_1892,_142030.jpg

Photo: Zde. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en

Johann Wilhelm Baur: Erysichthon. 1641.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_2AA-a-31-79

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/terms-use/copyright-and-permissions

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images accessed September 2022

___

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Executive Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.