Having come across across references to trees and to wooden construction in the Iliad and Odyssey, my curiosity was piqued, and I decided to gather a few examples where wood and trees were mentioned, to try and better understand what these meant in Homeric and Hesiodic poetry. Are there any special associations with trees or using wood? What kinds of trees are mentioned?

There are a number of similes with trees, for example at the death of Sarpedon:

He fell like some oak [drûs] or silver poplar [akherōis] or tall pine [pitus] to which woodmen [tektōn] have felled [ektemnein] with their newly whetted [neēkēs] axes [pelekus] upon the mountains to be [timber] for a ship— [485] even so did he lie stretched at full length in front of his chariot and horses, moaning and clutching at the blood-stained dust.

Iliad 16.482–484, adapted from Sourcebook[1]

The verse is formulaic and also occurs at the death of Asios (13.389–391.)

We see wood actually being cut ready to be used as fuel for cremations in the Iliad, for example for Patroklos’ funeral:

Then King Agamemnon sent men and mules from all parts of the camp, to bring wood [hulē], and Meriones, attendant [therapōn] to Idomeneus, was in charge over them. They went out [115] with woodmen’s [hulotomos] axes [pelekus] and strong ropes in their hands, and before them went the mules. Up hill and down dale did they go, by straight ways and crooked, and when they reached the heights of many-fountained Ida, they laid their long-edged bronze to many a tall branching oak [drûs] [120] that came thundering down as they felled [tamnein] it. They split [diaplēssein] them [= trees] and bound them behind the mules, which then wended their way as they best could through the thick brushwood [rhōpēion] on to the plain. All who had been cutting wood [hulotomos] bore logs [phitros], for so Meriones attendant [therapōn] to Idomeneus had bidden them. [125] They [= the Achaeans] placed them [the logs] in a row on the promontory [aktē] where Achilles 126 had marked out the place of a great tomb [ērion] for Patroklos and for his own self.

Iliad 23.110–126 adapted from Sourcebook

Here, the word used for tree is drûs, which according to LSJ[2] originally meant simply “tree” but is often taken to be “oak”; if this is the favored wood, it is dense and heavy, so this would have been hard work.

However, for building, at least for a temporary structure, we read about Achilles’ enclosure, when Priam, Idaios, and Hermes:

… came to the lofty dwelling of the son of Peleus [450] for which the Myrmidons had cut [keirein] beams [doru] of pine [elatē] and which they had built for their king; when they had built it they thatched it with coarse tussock-grass which they had mown out on the plain, and all round it they made a large courtyard [aulē], which was fenced with stakes [stauros] set close together. The gate was barred with a single bolt of pine [elatinos] which it took three men to force into its place, [455] and three to draw back so as to open the gate, but Achilles could draw it by himself.

Iliad 24.448–456, adapted from Sourcebook

And the Cyclops Polyphemus has a similar, but more rustic, enclosure:

we saw a great cave overhung with laurels [daphnē]. It was a station for a great many sheep and goats, and outside there was a large yard [aulē], [185] with a high wall round it made of stones built into the ground and of trees both pine [pitus] and oak [drus].

Odyssey 9.182–186, adapted from Sourcebook[3]

These two contrasting trees oak and pine, are sometimes mentioned together, as here when Nestor gives advice about chariot-racing:

326 I [= Nestor] will tell you [= Antilokhos] a sign [sēma], a very clear one, which will not get lost in your thinking. 327 Standing over there is a stump [xulon] of deadwood [aûos], a good reach above ground level. 328 It had been either an oak [drûs] or a pine [peukē]. And it hasn’t rotted away from the rains.

Iliad 23.326–328, adapted from Sourcebook

So far we have seen three words that denote some sort of pine or fir: elátinos (from elátē), pitus, and peukē. It is possible that these were different species:

- LSJ suggests elátē may be the silver fir, Abies cephalonica although if it is used for Achilles’ enclosure it may be the related Nordmann fir (Abies nordmanniana) based on the habitats mentioned in the respective Wikipedia articles for these trees[4].

- For both pitus and peukē LSJ suggests the Corsican pine, Pinus Laricio, or the Aleppo pine, Pinus halepensis.

There do not seem to be any clues in the passages quoted about the why those particular trees, other than perhaps metrical or formulaic reasons.

Achilles carries an ash spear—the only part of his armor and gear that Patroklos does not take:

He grasped two redoubtable spears that suited his hands, [140] but he did not take the spear of noble Achilles, so stout and strong, for none other of the Achaeans could wield it, though Achilles could do so easily— 143 the Pelian ash-spear [melia], which Cheiron had given to his philos father, 144 from the heights of Mount Pelion, to be death for heroes.

Iliad 16.140–144, adapted from Sourcebook

When Odysseus prepares a craft in which to leave Kalypsō’s island, he makes use of local materials indicated by Kalypsō:

So she gave him a great bronze axe [pelekus] that suited his hands; [235] it was sharpened on both sides, and had a beautiful olive-wood [elainos] handle fitted firmly on to it. She also gave him a sharp adze [skeparnon], and then led the way to the far end of the island where the largest trees [dendron] grew—alder [klēthrē], poplar [aigeiros] and pine [elatē], that reached the sky— [240] very dry [aûos] and well seasoned [perikēlos], so as to sail light for him in the water. Then, when she had shown him where the best trees [dendron] grew, Kalypsō, shining among divinities, went home, leaving him to cut [tamnein] timbers [doru], which he soon finished doing. He felled [ekballein] twenty in all, hewed [pelekân] them with the bronze, and adzed them smooth [xeîn], [245] squaring them by rule in good workmanlike fashion. Meanwhile Kalypsō, the shining goddess, came back with some augers [teretron], so he bored holes [tetraínein] with them and fitted together [harmozein] [the timbers] with bolts [gomphos] and rivets [harmoniā]. He made the improvised-vessel [skhediē] as broad as a skilled shipwright [250] makes the beam of a large vessel, and he filed a deck on top of the ribs, and ran a gunwale all round it. He also made a mast with a yard arm, [255] and a rudder to steer with. He fenced the raft all round with wicker [oisuinos] hurdles as a protection against the waves, and then he threw on a quantity of wood [húlē].

Odyssey 5.234–257, adapted from Sourcebook

The properties of the different timbers would make them suited to building his improvised vessel.

The nymph Kalypsō lives in a wooded place: we have already seen a selection of trees growing at one end of the island, but there are others on Ogygia around her home:

There was a large fire burning on the hearth, and one could smell from far the fragrant reek of burning cedar [kedros] [60] and sandalwood [thuon]. … Round her cave there was a thick wood [hulē] of alder [klēthrē], poplar [aigeiros], and sweet smelling cypress trees [kuparissos], [65] wherein all kinds of great birds had built their nests …. A vine [hēmeris] loaded with grapes was trained and grew luxuriantly about the mouth of the cave…

Odyssey 5.59–60, 63–65, 68–69, adapted from Sourcebook

The handle of Kalypsō’s axe is made from olive so that must also grow there. It is the wood most closely associated with Athena, and hence with Odysseus himself: he shelters under an olive tree when he arrives on Scheria—actually a pair of trees growing together, an olive [elaia] and a wild olive or buckthorn [phulia] (5.477), —he uses an olive stake to put out Polyphemus’ eye (Odyssey 9.320, 378, 382, 394), there is a large olive tree at the head of the harbor where Odysseus is put ashore on Ithaka (Odyssey 13.102), and perhaps most famously, his marital bed which he recalls to Penelope how he had made it himself:

For it was wrought to be a great sign [sēma]; it is a marvelous curiosity which I made with my very own hands. [190] There was a long-leaved [tanuphullos] bush [thamnos] of olive [elaia] growing within the precincts of the house, in full vigor, and about as thick as a bearing-post. I built my room round this with strong walls of stone and a roof to cover them, and I made the doors strong and well-fitting. [195] Then I cut off [apokoptein] the foliage [komē] of the long-leaved [tanuphullos] olive tree [elaia] and left the stump [kormos] standing. This I cut upwards [proemnein] from the root [rhiza] and then worked it [xeîn] with bronze well and skillfully, straightening my work to the line, and making it into a bed-prop. I then bored [tetrainein] it with an auger [teretron], and made it the center-post of my bed, at which I worked till I had finished it, [200] inlaying it with gold and silver; after this I stretched a hide of crimson leather from one side of it to the other. So you see I know all about this sign [sēma], and I desire to learn whether it is still there, or whether any one has been removing it by cutting [tamnein] down the olive tree [elaia] at its root [puthmēn].”

Odyssey 23.188–204, adapted from Sourcebook

The bed is well-constructed, and everything is made straight and orderly; it is a sign that identifies Odysseus at the very heart of his marriage, his home, and his community.

Hesiod provides references to trees, which should apply to an ideal ruler. At this stage it is open to debate whether or not this is applicable to Odysseus, who has, after all, just killed many young men; but once Athena has enforced a peace—and apart from the little matter of having to make another journey—it could fit in with the good rule that everyone mentions, and the “prosperous old age” promised by Teiresias:

Men who have straight dikē are never visited by Hunger

or by atē. Instead, at feasts, they reap the rewards of the works that they industriously cared about.

For them the earth bears much life-sustenance. On the mountains, the oak tree [drûs]

bears acorns [balanos] at the top and bees in the middle.Hesiodic Works and Days 230–233, adapted from Sourcebook[5]

The Works and Days also provides advice about how to use appropriate wood and how to work it properly:

When the power of the searing sun abates,

415 with its burning heat that makes men sweat, and when the autumn rains

of mighty Zeus arrive, as the human complexion turns

much lighter, and as the constellation Sirius

starts to travel much less over the heads of death-bound mortals

and starts to take much more enjoyment from the night,

420 then it is that wood [hulē] is most worm-free [adēktos] when it is cut [tamnein],

as the leaves [phullon] fall to the earth from the branches [ptorthos].

Then it is that you should be mindful [memnēmenos] to cut wood [hulotomeîn], which is now the seasonal task.

Then you can cut [tamnein] out a three-foot length for a mortar and a three-cubit length for a pestle,

and a seven-foot length for an axle. That is the way that is fitting.

425 And if you make it eight feet, then you can cut [tamnein] out of it the head of a mallet.

Cut [tamnein] out a three-span length for the segment of an oxcart the length of ten quarter-feet.

There are also many kinds of wood [kâla] used for bent shapes. When you find a tree with the shape of a plow-base [guēs],

take it right home, whether you find it on a mountainside or in the field,

especially if it is holm-oak [prînos], for it is the most sturdy for oxen to plow with,

430 when the servant of Athena [a carpenter] fixes it to the stock of the plow

with pegs [gamphos] and fastens it to the yoke-pole.

And take the trouble to have two plows in the household,

one with a natural curve and another jointed into a curve. It is better this way.

This way, if you break the one, you have the other to hitch up to your oxen.

435 Yoke-poles made of laurel [daphnē] or elm-wood [ptelea] are the most worm-free [akios].

The same goes for stocks made of oak [drûs] and for plow-bases made of holm-oak [prînos].Hesiodic Works and Days 414–436, adapted from Sourcebook

This is practical advice, based on the properties of wood and the best season to cut it.

- prînos, holm-oak (429), is given in LSJ as Quercus ilex, which, according to Wikipedia, “the wood is hard and tough, and has been used since ancient times for general construction purposes as pillars, tools, wagons (as mentioned in Hesiod, Works and Days …), vessels and wine casks. It is also used as firewood and in charcoal manufacture.”[6]

- daphnē laurel or sweet bay (435), is given in LSJ as Laurus nobilis. One myth is that the nymph, Daphne, was transformed into the tree to escape the pursuit of Apollo; and henceforth the leaves were used for the prize-winners’ garlands at the Pythian Games.[7]

The association between nymphs and trees—seen with Kalypsō and with Daphne—is also evident in the Homeric Hymn (5) to Aphrodite. The goddess decides to have her child reared by nymphs:

They mate with Seilēnoi or with the sharp-sighted Argos-killer,

making love [philotēs] in the recesses of lovely caves.

When they are born, firs [elatē] and oaks [drûs] with lofty boughs

265 spring out of the earth, that nurturer of men.

Beautiful trees, flourishing on high mountains,

they stand there pointing to the sky, and people call them the sacred places [temenos]

of the immortal ones. Mortals may not cut them down [keirein] with iron.

But when the fate [moira] of death is at hand for them,

270 these beautiful trees [dendron] become dry, to start with,

and then their bark [phloios] wastes away, and then the branches [ozos] drop off,

and, at the same time, the psūkhē goes out of them, as it leaves the light of the sun.Homeric Hymn (5) to Aphrodite, 262–272, adapted from Sourcebook[8]

Yet again, we see fir and oak mentioned together. And many of the names for different species of tree are feminine in grammatical gender, so perhaps that relates to why, personified, they are female nymphs.

The tree-nymphs are also mentioned as growing in a sacred space or precinct [temenos]. Here are a few more examples:

So he [= Achilles] killed Eëtion, 417 but he did not strip him of his armor—at least he had that much decency in his heart [thūmos]— 418 and he honored him with the ritual of cremation, burning him together with his armor. 419 Then he heaped up a tomb [sēma] for him, and elm trees [ptelea] were generated [phuteuein] around it [420] by mountain nymphs who are daughters of Zeus, holder of the aegis.

Iliad 6.416–420, adapted from Sourcebook

There is a similar passage in Philostratus On Heroes; while this is not Homeric, the words given to the Vinedresser must have been inspired by the Iliad:

9.1 … Protesilaos lies buried not at Troy but here on the Chersonesus. This large tumulus [kolōnos] over here on the left no doubt contains him. The nymphs generated [phuein] these elms [ptelea] [that you see here] around the tumulus [kolōnos], and they wrote, so to speak, the following decree concerning these trees [dendron]: 9.2 “Those branches [ozos] that turn toward Ilion [= Troy] will blossom [antheîn] early and will then immediately shed their leaves [phullon] and perish before their season [hōrā]—for this was also the life experience [pathos] of Protesilaos—but a tree [dendron] on its other side will live and prosper.” 9.3 All the trees [dendron] that do not stand around the tomb [sēma], such as these trees [dendron] [that you see right over here] in the grove [kēpos], have strength in all their branches [ozos] and flourish according to their particular nature.

Hērōikos 9.1–3, adapted from translation by Gregory Nagy[9]

Such groves of trees could also be sacred to the gods, although a temenos could also be a precinct marked off as the domain for a ruler. Nausicaa instructs Odysseus to follow her later into the town; she says:

you will see a beautiful grove [alsos] of black-poplars [aigeiros] by the roadside dedicated to Athena; it has a well in it and a meadow all round it. Here my father has a precinct [temenos] of rich garden ground, about as far from the town as a man’s voice will carry. [295] Sit down there and wait for a while…

Odyssey 6.291–295, adapted from Sourcebook

Other trees are mentioned in connection with other gods. For example, in Odyssey 14.327–8 there is reference to the oak tree [drûs] of Zeus at Dodona, and Dionysus we know is connected with the grape-vine, but also with ivy—and, perhaps unexpectedly, with laurel:

The rich-haired Nymphs received him in their bosoms from the lord his father and fostered and nurtured him carefully in the dells of Nysa, where by the will of his father he grew up in a sweet-smelling cave, being reckoned among the immortals. But when the goddesses had brought him up, a god oft hymned, then began he to wander continually through the woody [hulēeis] coombes, thickly wreathed with ivy [kissos] and laurel [daphnē].

Homeric Hymn (26) to Dionysus, adapted from translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White[10]

What other trees are mentioned as associated with sacred spaces? How consistent are the associations between particular trees with particular gods? What other varieties of tree are there, and are they put to practical use?

Join me in the Forum to share more examples of wood and trees in Homer and Hesiod.

Look out for part 2, coming soon.

Related posts

For further analysis of the passage from Odyssey 5, and the craft of shipbuilding, see

“The improvised craft”

For vocabulary relating to a selection of fruit trees, see

“Food and drink | Part 1: Homer and Hesiod”

Selected vocabulary

Based on definitions at LSJ and Autenrieth[11].

ádēktos [ἄδηκτος] adj. not gnawed or worm-eaten

aígeiros [αἴγειρος, αἰγείρου, ἡ] black poplar

akhrōís [ἀχερωίς, ἡ] white poplar

ákios [ἄκιος] adj. not worm-eaten

antheîn [ἀνθεῖν] to bloom, blossom

álsos [ἄλσος, ἄλσεος, τό] grove, hallowed precinct

apokóptein [ἀποκόπτειν] to chop off, cut off

aûos [αὖος] adj. dry

bálanos [βάλανος, βαλάνου, ἡ] acorn

dáphnē [δάφνη] laurel, bay

déndron [δένδρον, δένδρου, τό] tree

diaplēssein [διαπλήσσειν] to break in pieces, cleave, split

dóru [δόρυ, δόρατος/δουρός, τό] stem, tree; shaft of a spear

drûs [δρῦς] tree, oak

gúēs [γύης, γύου, ὁ,] curved piece of wood used in a plow

ekbállein [ἐκβάλλειν] to fell, cut out

ektémnein [ἐκτέμνειν] to cut out, cut down, hew

elaía [ἐλαία, ἐλαίας, ἡ] olive-tree

eláinos [ἐλάινος] adj. of olive-wood

elátē [ἐλάτη, ἡ] pine, fir

elátinos [ἐλάτινος] adj. of fir or pine-wood

gómphos [γόμφος] wooden nail, peg, bolt, dowel

harmózein [ἁρμόζειν] to fit together, join

harmoníā [ἁρμονία] joint, fastening

hēmerís [ἡμερίς, ἡμερίδος, ἡ] cultivated vine

húlē [ὕλη] wood, forest; cut wood, firewood

hulēeis [ὑλήεις] adj. woody, wooded

hulotomeîn [ὑλοτομεῖν] to cut or fell wood

hulotómos [ὑλοτόμος] noun: wood-cutter, woodman; adj.: wood-cutting

kâlon [κᾶλον, καλοῦ, τό] pl. kâla logs (for burning), timber

kédros [κέδρος, κέδρου, ἡ] cedar-tree, cedar-wood

keírein [κείρειν] shear off, cut down

kēpos [κῆπος, κήπου, ὁ] garden, orchard, plantation

kissós [κισσός, κισσοῦ, ὁ] ivy

klēthrē [κλήθρη, ἡ] alder

kormós [κορμός, κορμοῦ, ὁ] trunk, log

kupárissos [κυπάρισσος, κυπαρίσσου, ἡ,] cypress

melía [μελία, μελίης, ἡ] ash

neēkēs [νεηκής] newly whetted

oisúinos [οἰσύινος] adj. of willow, osier

ózos [ὄζος, ὄζου, ὁ] branch, twig, shoot

pelekân [πελεκᾶν] to hew, shape with an ax

pélekus [πέλεκυς. πέλεκεος/πέλεκεως, ἡ] ax, hatchet

períkēlos [περίκηλος] adj. very dry, well-seasoned

peúkē [πεύκη, πεύκης, ἡ] pine, fir

phitrós [φιτρός, φιτροῦ, ὁ] trunk, block, log

phloiós [φλοιός, φλοιοῦ, ὁ] bark

phulia [φυλία, φυλίης ἡ] wild olive, or buckthorn

phúllon [φύλλον, φύλλου, τό] leaf

pítus [πίτυς, πίτυος, ἡ] pine

príninos [πρίνινος] adj. made from the prînos

prînos [πρῖνος, ἡ, ὁ] holm-oak

protémnein [προτέμνειν] cut off in front, cut short, prune

pteléa [πτελέα, πτελέης, ἡ] elm

ptórthos [πτόρθος, πτόρθου, ὁ] young branch, shoot, sapling

puthmēn [πυθμήν, πυθμένος, ὁ] bottom, foundation, root

rhíza [ῥίζα, ῥίζης, ἡ] root

rhōpēion [ῥωπήϊον, ῥωπήϊου, τό] undergrowth, brushwood

skhedíē [σχεδίη, σχεδίης, ἡ] raft, float, such as was made off-hand

sképarnon [σκέπαρνον, σκεπάρνου, τό] adze

staurós [σταυρός] stake, pale, pile

támnein [τάμνειν] to cut, cut down, fell

tanúphullos [τανύφυλλος] adj. with long or slender leaves

téktōn [τέκτων, τέκτονος, ὁ] worker in wood, carpenter, joiner

témenos [τέμενος, τεμένεος, τό] sacred precinct

téretron [τέρετρον, τέρετρου, τό] auger, borer, gimlet

tetraínein [τετραίνειν] to pierce with holes, perforate, bore

thámnos [θάμνος, θάμνου, ὁ] thicket, bush, shrub

thúon [θύον, θύου, τό] a fragrant wood; thyine-wood, citron-wood

xeîn [ξεῖν] to scrape, hew smooth, polish

xúlon [ξύλον, ξύλου, τό] singular: piece of wood, log, beam, post; plural, wood cut and ready for use, firewood, timber

Notes

1 Sourcebook: Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook: Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English. Gregory Nagy. 2013.

https://chs.harvard.edu/book/the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours-sourcebook/

Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://chs.harvard.edu/primary-source/homeric-iliad-sb/

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

2 LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones, with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus

3 Sourcebook: Odyssey Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://chs.harvard.edu/primary-source/homeric-odyssey-sb/

Greek text Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919.

Online at Perseus

4 Wikipedia article on Abies cephalonica

Wikipedia article on Abies nordmanniana

5 Sourcebook: Hesiodic Works and Days Translated by Gregory Nagy

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://chs.harvard.edu/primary-source/hesiod-works-and-days-sb/

Greek text: Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Works and Days. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Available on Perseus

6 Wikipedia article on Quercus ilex

7 Versions of the myth of Daphne are available on theoi.com

8 Sourcebook: Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite translated by Gregory Nagy

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://chs.harvard.edu/primary-source/homeric-hymn-to-aphrodite-sb/

Greek text: Anonymous. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

9 Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours 14§23, Hour 14 Text G.

and Greek text in footnote 21.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

10 English and Greek texts: Anonymous. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

11 Autenrieth: Georg Autenrieth. 1891. A Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges. New York. Harper and Brothers.

Online at Perseus

Texts accessed June 2022.

Image credits

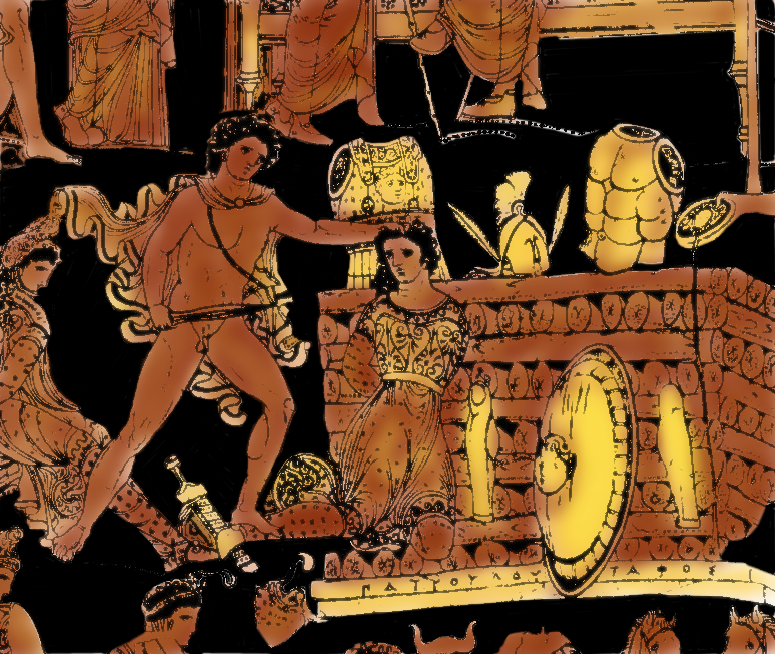

Funeral of Patroklos, showing the logs on the pyre. Detail from 1884 engraving taken from a Greek Apulian Red-figure Volute Krater, attributed to the Darius Painter, c. 330 BCE.

Cropped and colorized by Kathleen Vail, user AishaAbdel, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Trees in Athens National Gardens

Photo: Georgios Liakopoulos, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Cave with trees

Photo: τέλιος Δ , Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 2.0, via Flickr

Bronze Age ax from Crete

Photo: Chris 73, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Traditional wooden plough, Folklore Museum, Petrokerass, Central Macedonia, Greece

Macedonian Heritage, Prof. Vlasis Vlasidis, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Cephalonian fir and Corsican pine on Mount Parnitha

Photo: Chavakismanolis, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

Ferdinand Georg Waldmüller: Elms, Prater-landscape 1831

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Grove of black poplar

Photo: Christian Fischer, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Oak tree at Dodona

Photo: Zde, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images accessed June 2022.

__

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Executive Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.