As a complement to the post on the two shorter Homeric Hymns to Aphrodite, this time I wanted to look at the two short Homeric Hymns to Artemis, #9 and #27. Unlike those for Aphrodite, there is not a longer Hymn to Artemis.

As before, I want to think about what kind of narrative or myth might have accompanied either of these Hymns, if we take them as prooemia, and to see what key words stand out. Do they have much in common, or do they concentrate on different aspects of Artemis?

And recalling the different and opposing characteristics of Aphrodite and Artemis seen, for example, in Euripides’ Hippolytus, is there evidence of this in these texts?

First, here is the text, based on the translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White[1], incorporating translations and wording from Gregory Nagy, and further adapted by myself.

Homeric Hymn (9) to Artemis

[1] Muse, sing of Artemis, sister of the Far-shooter, the maiden [parthenos] pourer-of-arrows [io-khéira], who was fostered with Apollo. She waters her horses from Meles deep in reeds, and swiftly drives her all-golden chariot through Smyrna [5] to vine-clad Klaros where Apollo, god of the silver bow [argurotoxos], sits waiting for the far-shooting [hekatēbolos] goddess pourer-of-arrows [io-khéaira].

So, with all this said, I say to you [= Artemis] now: hail and take pleasure [khaire], and along with you may all the other goddesses [take pleasure] from my song. As for me, I sing you first of all and from you do I start off [arkhesthai] to sing. And, having started off from you, I will move ahead and shift forward [metabainein] to the rest of the humnos.[2]

The epithet io-khéaira is repeated, verses 2 and 5, so this is clearly an important concept in connection with Artemis in this hymn. The word is related to iós ‘arrow’ and the verb kheîn ‘pour, shed’ although some translations take it as if from khairein ‘rejoice in’, and translate as “delighting in arrows”.[3]

Having a silver bow [argurotoxos] is a frequent epithet of Apollo in the Iliad (eleven times) and Odyssey (three times); it is also used twice in the Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo, twice in Homeric Hymn (4) to Hermes, and once in Homeric Hymn (7) to Dionysus.

But the epithet hekatēbolos is usually applied to Apollo, both in the Homeric Hymns (seven times in Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo and once in Homeric Hymn (4) to Hermes), and in epic (five times in the Iliad and twice in the Odyssey), to the extent that the epithet on its own would be understood to refer to Apollo. So, along with the fact that she was reared with her brother, and the reference to his bow, may indicate a close connection between them in this hymn, and in particular in connection with their ability to shoot and hit people and bring about a sudden death, as described by Domenico Giuseppe Muscianisi in his essay on The Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo:

Artemis is presented as archer (199 ἰοχέαιρα) and twin of Apollo (ὁμότροφος Ἀπόλλωνι) [homótrophos Apóllōni]; Leto’s twins are generally responsible for sudden deaths of women and men respectively. Myth uses the image of the shooting of invisible arrows of disease; compare the myth of Niobe and the mirror-image repetition with which Odysseus asks his mother Antikleia if she died of sickness or after Artemis iokheaira smote her (Odyssey 11.171–173)..[4]

But Artemis, at least, is associated with the hunt, so we cannot ignore this aspect of her abilities with arrows and shooting. And Allen & Sikes[5] also note that she is referred to as hekēbolos in fragment 357 of Sappho and “on a Naxian inscription at Delos.”

Meles “deep in reeds” reminded me of the location of the nymph Salmacis, who, in Ovid’s account[6] was unwilling to go hunting, and lived where there were no reeds, by a spring made people lustful. So perhaps this detail is drawing on a traditional association, such that in this Hymn that Artemis’ chosen spot, where there are plenty of reeds, has the opposite effect, in keeping with Artemis’ chastity and predilection for the hunt.

As for the three place-names mentioned, Meles, Smyrna, and Klaros, the notes by Allen and Sikes suggest:

The marks of locality … are not of sufficiently PanHellenic importance to be merely “literary,” as would be, for example, the mention of Cyprus and Cythera in connexion with Aphrodite…. Nor is it impossible that the prelude was recited at a common festival of Apollo and Artemis; but we have no proof that such a festival existed, although there are Colophonian coins of Apollo “Klarios” and Artemis “Klaria”, dating from imperial times. The two deities, however, are not represented together on this coinage…; and the reference to the Clarian Apollo may have a mythological rather than a ritualistic significance.[7]

What kind of story might have followed this if it is a prooemium? Perhaps a story that emphasized the qualities of a mythological figure that contrasted those associated with Artemis and those associated with “all goddesses as well.”

Homeric Hymn (27) to Artemis

[1] I sing of Artemis, with golden spindle [khrusēlakatos], loud-calling,

the pure maiden [parthenos], shooter of stags, pourer-of-arrows [io-khéaira] ,

own sister of Apollo with the golden sword.

Over the shadowy hills and windy peaks

[5] she draws her all-golden [pan-khruseon] bow [tóxon], rejoicing in the chase,

and sends out grievous shafts [bélos]. The tops tremble

of the high mountains, and the tangled wood echoes

terrifically [deinon] with the outcry of beasts: the earth shudders,

and the sea [pontos] full of fish. But she [=Artemis] with a bold heart

[10] turns every way destroying the stock of wild beasts:

but when the pourer-of-arrows [io-khéaira] has taken her fill of looking out for wild beasts

and has cheered her mind [noos], she slackens her well-bent bow

and goes to the great house of her dear [philos] brother

Phoebus Apollo, to the rich dēmos of Delphi,

[15] there to order the lovely song-and-dance [khoros] of the Muses and Graces.

There she hangs up her curved bow and her arrows,

and, being gracefully [adv. from kharis] arrayed [kosmos] about her skin,

heads and leads the dances [khoroi], while all they utter their divine [ambrosia] voice,

singing of neat-ankled [kallisphuros] Leto, how she bore children

[20] supreme [aristoi] among the immortals both in determination [boulē] and in deed.Hail-and-take-pleasure [khairete], children of Zeus and of lovely-haired Leto:

but as for me, I will keep you in mind [memnēmai] along with the rest of the song [aoidē].Translation Hugh G. Evelyn-White, incorporating translations and wording from Gregory Nagy, and further adapted by Sarah Scott.[8]

In Hymn 9, Apollo has a silver bow; in this Hymn, the artifacts of both gods are of gold. Apollo is referred to as having a golden sword [khrusaoros], and this epithet is used also of Apollo twice in the Iliad, and once in Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo, but it is also used once of Demeter in Homeric Hymn (2) to Demeter. In Hymn 27 Artemis has a golden spindle [khrusēlakatos]: ēlakatē means spindle, although according to LSJ[9] and Brill[10] the scholia want to explain this compound word as “golden arrow.” Perhaps the scholia want to tie this word in to the hunting which features more frequently with Artemis. Allen and Sikes, in their commentary on Homeric Hymn (5) to Aphrodite, verse 16—where the epithet is again used of Artemis—say:

The sense “of golden distaff” is quite unsuited to the character of Artemis. The addition of “κελαδεινή” [keladeinē] in several passages is a further argument. The epithet refers to the goddess as a hunter who “calls on the hounds”[11]

However, there may be a clue in a passage from Herodotus, although a different term is used:

The Delian girls and boys cut their hair in honor of these Hyperborean maidens, who died at Delos; the girls before their marriage cut off a tress and lay it on the tomb, wound around a spindle [átraktos] (this tomb is at the foot of an olive-tree, on the left hand of the entrance of the temple of Artemis); the Delian boys twine some of their hair around a green stalk, and lay it on the tomb likewise.

Herodotus Histories 4.34.1–4.34.2[12]

The term used here, átraktos, means spindle, but, like ēlakatē, is also used elsewhere to refer to an arrow[13]. The spindle or distaff may be a reference to the girls’ unmarried status. In the English language, a “spinster” is an unmarried woman, literally one who spins. And in Hymn (5) to Aphrodite, the epithet khrusēlakatos is used in a context where it says that Aphrodite could not subdue Artemis in lovemaking:

The second is the renowned Artemis, she of the golden shafts [khrusēlakatos]: never

has she been subdued in lovemaking [philotēs] by Aphrodite, lover of smiles [to whom smiles are phila].

For she takes pleasure in the bow and arrows, and the killing of wild beasts in the mountains,

as well as lyres, groups of singing dancers, and high-pitched shouts of celebration.

20 Also shaded groves and the city of dikaioi men.Homeric Hymn (5) to Aphrodite 16–20, adapted from Sourcebook[14]

Less controversial in Hymn 27 is the reference in verse 5 to the “all-golden bow” [pankhrusea toxa]. Both silver and gold are often used for artifacts belonging to the gods.

Artemis’ hunting in this Hymn is imagined in the hills, mountains, and woods, but the effect is felt on land and sea. So it may be imagined that she hunts all types of creatures.

In the visual arts Artemis is usually depicted with her bow, and either a quiver on her back or arrow in her hand, which fit with her epithets. Sometimes she is shown associated with a deer, and there are other stories where this animal is incorporated into the myth, for example Agamemnon’s sacrifice (or substituted sacrifice) of his daughter Iphigenia, for example, as told in the Cypria:

17 They [=the Achaeans] summon her [=Iphigeneia] as if for a marriage to Achilles and

18 are about to sacrifice her. But Artemis snatches her away and

19 carries her to Tauris and makes her immortal, meanwhile placing a deer instead of the girl

20 on the altar.Proclus’ Summary of the Cypria, attributed to Stasinus of Cyprus{p104} 17–20, Sourcebook [15]

As in Hymn 9, in Hymn 27 Artemis joins her brother Apollo, but this time in another location, Delphi, which is perhaps most closely associated with him, and would be pan-Hellenic. However, Sikes and Allen sound a cautionary note:

The lines do not prove that the writer had any idea of a common cult of Apollo and Artemis at Delphi. The goddess simply visits her brother to take part in the chorus of Muses and Graces … . Artemis, however, has some connexion with Delphi, although she is not mentioned in the earliest myths of the oracle and temple. This connexion gave her the cult-names “Δελφινία” [Delphinía] (Attica, Thessaly) and, in imperial times, “Πυθίη” [Pythíē] (Miletus). At Delphi itself, as Farnell (Cults ii. p. 467) remarks, we have few traces of her cult; an inscr. (379 B.C.) records an Amphictyonic oath to Apollo, Leto, and Artemis…, and slaves (? female) were sometimes emancipated in the name of Apollo and Artemis …. The eastern pediment of the Delphian temple represented Apollo, Artemis, Leto, and the Muses, but no trace of this sculpture has been discovered.[16]

In this Hymn, both Artemis and Apollo are being linked to their mother, Leto, and perhaps to the story of their birth, which is given in the Homeric Hymn (3) to Apollo. Further, the epithet applied here to Leto, “neat-ankled,” [kallisphuros] is discussed in Danielle Winkler’s Ankle and Ankle Epithets where she says:

Leto only appears as καλλίσφυρος in immediate connection with her giving birth; and it seems that the epithet usually appears in connection with sexual union or procreation.[17]

So Leto is perhaps being contrasted with Artemis, who is not usually connected with these activities.

Artemis does, however, later take over the role previously associated with Eileithyia in relation to assisting others in childbirth. Roger D. Woodard in his post on Linear B po-re-na po-re-si and po-re-no mentions a couple of examples where the goddesses Eileithyia and Artemis receive the same epithet, lusizōnos, and are both mentioned in similar textile dedications[18]

So perhaps this Hymn could connect to a myth with a theme of birth, either by way of association with Leto, or with Artemis herself.

In verse 20 of Hymn 27, both Apollo and Artemis are described as “supreme [aristoi] among the immortals both in determination [boulē] and in deed.” Might that suggest an occasion where they worked together in some way?

One example might be the story of Niobe, as mentioned by Muscianisi in the passage quoted above ; here is part of a version of the myth which is told in the Iliad by Achilles, talking to Priam:

602 Even Niobe, the one with the beautiful hair, thought of eating grain, 603 the one who had twelve children, and all of them were killed in the palace, 604 six daughters and six sons in the bloom of youth. [605] Apollo killed the sons, shooting from his silver [argúreos] bow [biós]. 606 He was angry at Niobe—and the daughters were killed by Artemis, pourer of arrows [io-khéaira]— 607 angry because she [= Niobe] tried to make herself equal to Leto, the one with the beautiful cheeks. 608 She [= Niobe] said that she [= Leto] gave birth to two, while she herself produced many. 609 So the two of them [= Apollo and Artemis], only two though they were, destroyed the many.

Homeric Iliad 24.602–609, adapted from Sourcebook[19]

Or are there episodes in one myth featuring Apollo that bears similarities to a myth featuring Artemis, where their determination and deeds are highlighted, and / or where the god and goddess are described as aristos?

Nausicaa, playing with her handmaidens after washing clothes at the shore, is compared to Artemis, and the epithet io-khéaira is used:

[100] they threw off the veils that covered their heads and began to play at ball, while Nausicaa of the white arms sang for them. As the huntress Artemis, pourer-of-arrows [io-khéaira], goes forth upon the mountains of Taygetos or Erymanthos to hunt wild boars or deer, [105] and the wood-nymphs, daughters of Aegis-bearing Zeus, take their sport along with her (then is Leto proud at seeing her daughter stand a full head taller than the others, and eclipse the loveliest amid a whole bevy of beauties), even so did the untamed maiden [parthenos] outshine her handmaids.

Odyssey 6.100–109, adapted from Sourcebook[20]

In Hymn 27, we see Artemis hunting, then joining a song-and-dance about Leto. In the Odyssey Nausicaa and her servants have been washing clothes, not hunting in the hills, but the washing of clothes has been connected with the prospect of marriage. In a dream Athena suggested that Nausicaa should do this:

“…so that you may have everything ready as soon as possible, for all the best young men [35] throughout your own dēmos are courting you, and you are not going to remain a young girl much longer”

Odyssey 6.34–35, Sourcebook

so perhaps there is a hint that they are “hunting” for husbands. Then the game that Nausicaa and her maids play is like a form of song and dance, and although they do not sing of Leto, she is still invoked in the simile.

And maybe a story like this one could be associated with the Hymn.

All my suggestions are only conjectures, as the starting point for discussion.

Which myths do you think might fit with these Hymns?

Notes

1 English translation and Greek text from The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Available online at Perseus or at Scaife

2 Gregory Nagy has formulated this for khaire/khairete which occurs in many of the Homeric Hymns: “Now, at this precise moment, with all this said, I greet you, god (or gods) presiding over the festive occasion, calling on you to show favor [kharis] in return for the beauty and the pleasure of this, my performance.” but in translation also uses a more manageable “Hail-and-take-pleasure” I have incorporated his translation of this and of the final line, taken from Nagy, Gregory. 2011. “The earliest phases in the reception of the Homeric Hymns.” p328. Included in Nagy, Gregory. Short Writings III. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-the-earliest-phases-in-the-reception-of-the-homeric-hymns/

3 LSJ. LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus: entry for io-khéaira

4 Domenico Giuseppe Muscianisi 2020/06.11. “The Circle of Fame: Apollo, the Corps de Ballet, and the Song of the Muses at Delphi” §3.0.2.(a). Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-circle-of-fame-apollo-the-corps-de-ballet-and-the-song-of-the-muses-at-delphi/

5 Thomas W. Allen and E.E. Sikes. 1904. Commentary on the Homeric Hymns. London.

Commentary to Hymn 9 to Artemis,

Online at Perseus

6 Ovid Metamorphoses 4.285–398,

Translation by Arthur Golding Online at Perseus or

Translation by A.S. Kline at Poetry in Translation

The episode was discussed by Jan-Mathieu Carbon in the Online Open House “A Middle Ground in the Middle Sea: the “Marriage” of Salmakis and Halikarnassos.” .

7 Thomas W. Allen and E.E. Sikes. 1904. Commentary on the Homeric Hymns. London.

Commentary to Hymn 9 to Artemis,

Online at Perseus

8 English translation and Greek text from the edition of Hugh G. Evelyn-White,

Online at Perseus

Online at Scaife

Lines translated by Gregory Nagy from “The earliest phases in the reception of the Homeric Hymns.” p328.

9 LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus: entry for χρυσηλάκατος [khrusēlákatos]

10 Brill: Montanari, Franco. 2015. The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek. English edition edited by Madeleine Goh & Chad Schhroeder. Brill, Leiden and Boston.

11 Thomas W. Allen and E.E. Sikes. 1904. Commentary on the Homeric Hymns. London.

Commentary to Hymn 5 to Aphrodite, 16.

Online at Perseus

12 Herodotus Histories Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

Online at Scaife

13 LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus: entry for ἄτρακτος [átraktos]

14 Sourcebook: Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite Translated by Gregory Nagy.

Online at Kosmos Society Text Library

15 Sourcebook: Epic Cycle, Proclus’ Summary of the Cypria, attributed to Stasinus of Cyprus, translated by Gregory Nagy, revised by Eugenia Lao.

Online at Kosmos Society Text Library

16 Thomas W. Allen and E.E. Sikes. 1904. Commentary on the Homeric Hymns. London.

Commentary to Hymn 27 to Artemis, 13

Online at Perseus

17 Daniela Winkler. 2017. Ankle and Ankle Epithets in Archaic Greek Verse. Cambridge, MA., chapter 4 “καλλίσφυρος and τανίσφυρος in the Homeric Hymns”

Second, online edition 2017. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_WinklerD.Ankle_and_Ankle_Epithets_in_Archaic_Greek_Verse.1977

18 Roger D. Woodard. 2018.02.04. “Linear B po-re-na, po-re-si, and po-re-no-” §18. Classical Inquiries.

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/linear-b-po-re-na-po-re-si-and-po-re-no/

19 Sourcebook, Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power

Online at Kosmos Society Text Library

20 Sourcebook, Homeric Odyssey, Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power

Online at Kosmos Society Text Library

Texts accessed November 2021.

Image credits

Attributed to The Klügmann Painter. Artemis, with arrow and bow. Attica, c 440 BCE

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Attributed to the Pan Painter. Artemis pouring wine for Apollo: red-figured lekythos. Attica, 480 – 460 BCE.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

“Diana of Versailles“. Roman copy of Greek sculpture by Leochares.

Photo: Commonists. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

Silver coin from Ephesus showing Artemis on one side, and a deer on the other. c 258 – 202 CE.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

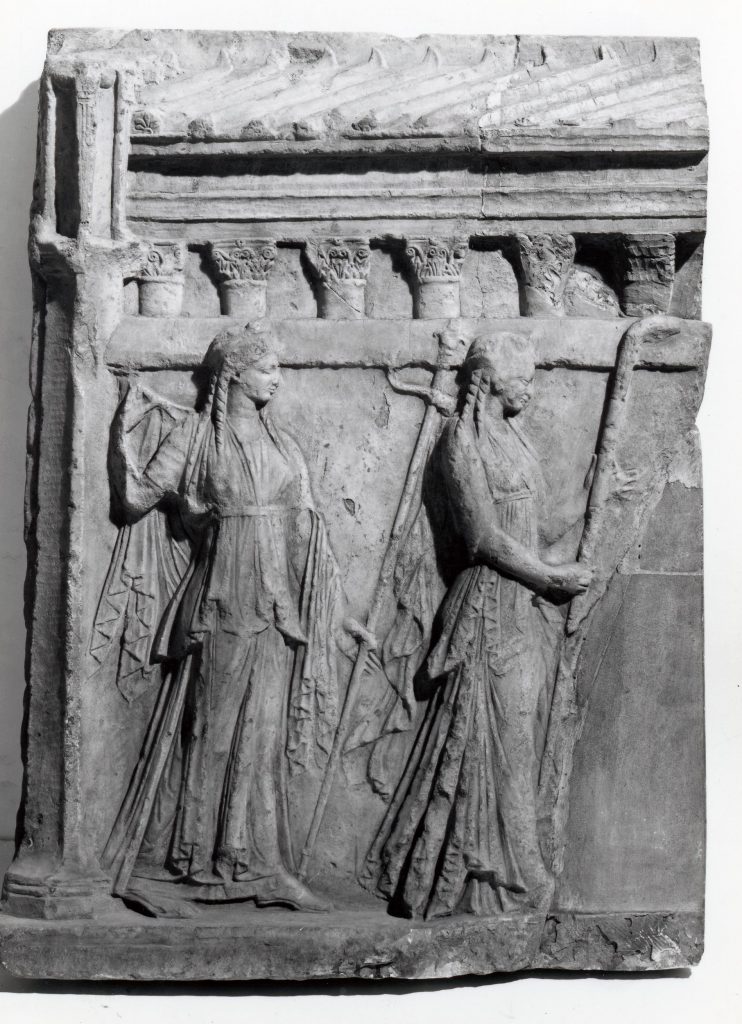

Artemis and Leto: relief c 100 BCE – 1 BCE.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Apollo and Artemis. Donto of Attic red-figure cup. c 470 BCE.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attributed to The Berlin Painter. Artemis, detail from trefoil-mouth oinochoe. Attic c 490 BCE – c 460 BCE.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images accessed November 2021

___

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Executive Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.