This post has been inspired by recent posts regarding the Olympic Games. It consists of some thoughts that occurred to me when reading the posts, and various other musings from reading a number of sources over the years. What struck me most was the relative absence of women in the written and pictorial record of ancient sports. This is reflected, too, in the absence of women in the early modern Olympics, as noted in Ϙ’s post.[1] The first modern Olympics were in 1896, but women did not compete until 1900, and it was not until this year, 2024, that the numbers of male and female athletes in the Games were equal.

Definitions of the parameters of this post are contested. Most sport is physical and competitive, but not all of it. I would not say darts and pool are physical, nor is breakdancing always formally competitive. In ancient times women engaged in hunting, warfare, and in dance and religious ritual, some of which are sometimes defined as sport. The contested definition of ‘woman’ has become an issue in the current games. But for the purposes of this post, I persist with loose definitions and partial readings, in the hope that some Kosmonauts may be prompted to add to what I write, and perhaps clarify some issues. I begin with myth, and continue with consideration of sporting women in Athens and other cultures.

The classical mythical sporting heroine was Atalanta, from Calydon in North West Greece. She was a huntress who took part successfully in the Calydonian boar hunt, but her prowess in wrestling and running is demonstrated in what happened next. The story is told by Apollodorus:[2]

Grown to womanhood, Atalanta kept herself a virgin, and hunting in the wilderness she remained always under arms. The centaurs Rhoecus and Hylaeus tried to force her, but were shot down and killed by her. She went moreover with the chiefs to hunt the Calydonian boar, and at the games held in honor of Pelias she wrestled with Peleus and won. Afterwards she discovered her parents, but when her father would have persuaded her to wed, she went away to a place that might serve as a racecourse, and, having planted a stake three cubits high in the middle of it, she caused her wooers to race before her from there, and ran herself in arms; and if the wooer was caught up, his due was death on the spot, and if he was not caught up, his due was marriage. When many had already perished, Melanion came to run for love of her, bringing golden apples from Aphrodite, and being pursued he threw them down, and she, picking up the dropped fruit, was beaten in the race. So Melanion married her.

Three major themes emerge from this story: first, Atalanta was a runner and a hunter. Second, she was not from Athens, and, third, she entered into a footrace, indeed, many footraces, to decide who was to be her husband. A further minor theme is the use of apples to determine the fate of a woman, a theme that recurs later.

A second mythical huntress and sportswoman was Cyrene, whose story is told by Pindar:[3]

She did not care for pacing back and forth at the loom, nor for the delights of luncheons with her stay-at-home companions; instead, fighting with bronze javelins and with a sword, she killed wild beasts, providing great restful peace for her father’s cattle; but as for her sweet bed-fellow, sleep, she spent only a little of it on her eyelids as it fell on them towards dawn. Once the god of the broad quiver, Apollo who works from afar, came upon her wrestling alone and without spears with a terrible lion. Immediately he called Cheiron from out of his halls and spoke to him: “Leave your sacred cave, son of Philyra, and marvel at the spirit and great strength of this woman; look at what a struggle she is engaged in, with a fearless head, this young girl with a heart more than equal to any toil; her mind is not shaken with the cold wind of fear. From what mortal was she born? From what stock has this cutting been taken, that she should be living in the hollows of the shady mountains and putting to the test her boundless valor? Is it lawful to lay my renowned hand on her? And to cut the honey-sweet grass of her bed?”

Cheiron approved the union and continued with a prophecy:

You came to this glen to be her husband, and you will bear her over the sea to the choicest garden of Zeus, where you will make her the ruler of a city, when you have gathered the island-people to the hill encircled by plains. And now queen Libya of the broad meadows will gladly welcome your glorious bride in her golden halls. There she will right away give her a portion of land to flourish with her as her lawful possession, not without tribute of all kinds of fruit, nor unfamiliar with wild animals.

Joel Christensen[4] commented on this story:

This story is really exceptional in Greek myth and history . . . here we have a female beast-slayer who follows the classic pattern of killing a monster and gaining a kingdom.

Callimachus also said that Cyrene, who was Hypseus’ daughter, took part in Pelias’ funeral games at Iolcos, and won a hunting contest. Challimachus’s writing was in a hymn to Artemis, who was often depicted with animals and was the goddess of hunting. Challimachus described (in one translation) Cyrene as a comrade to Artemis:

Yea and Cyrene thou madest thy comrade, to whom on a time thyself didst give two hunting dogs, with whom the maiden daughter of Hypseus beside the Iolcian tomb won the prize.[5]

Atalanta and Cyrene, then, were hunters and athletes. The Iliad tells of another role for women in games, in this case, as prizes in Patroclus’ funeral games. Homer describes Achilles as preparing prizes for the games:

from his ships brought forth prizes; cauldrons and tripods and horses and mules and strong oxen and fair-girdled women and grey iron.[6]

And, later:

Then the son of Peleus forthwith ordained in the sight of the Danaans other prizes for a third contest, even for toilsome wrestling — for him that should win, a great tripod to stand upon the fire, that the Achaeans prized amongst them at the worth of twelve oxen; and for him that should be worsted he set in the midst a woman of manifold skill in handiwork, and they prized her at the worth of four oxen.[7]

Notwithstanding exemplars and role models of hunters and sportswomen from myth and the pantheon, women’s actual sporting activity was rarely reported in ancient times. A further Olympics post[8] reminds us of the games that took place in Minoan Crete. Surviving frescoes show young men boxing and young men and women leaping over bulls.[9] If anything more can be inferred from the frescoes about women, it is that they were spectators. Other physical activity may have included dancing, and one of my favourite images from Crete is the woman apparently dancing holding snakes, and with a cat on her head. There is, however, no suggestion that this was a competitive sport.

So, in myth women were hunters and athletes and prizes in men’s sports, one of them even worth four oxen. In ancient Crete they were spectators, but they were not even that in the ancient Olympic Games. In her post[10] Sarah explored Pindar’s <Olympian Odes, which made no mention of women competitors or spectators. Goddesses, muses and various female supernatural beings are invoked. Mothers are occasionally mentioned. Cities where athletes originated are cast as female. But there is no mention of women engaged in physical activity.

Pausanias wrote extensive descriptions of Olympia and its environs,[11]detailing buildings and statues and incorporating stories and anecdotes of the Games. He was, though, slightly ambiguous about women’s participation. He starts by being unequivocal:

As you go from Scillus along the road to Olympia, before you cross the Alpheius, there is a mountain with high, precipitous cliffs. It is called Mount Typaeum. It is a law of Elis to cast down it any women who are caught present at the Olympic games, or even on the other side of the Alpheius, on the days prohibited to women.[12]

Nevertheless, he continues by telling the story of Callipateira (or perhaps Pherenice) who gained admission by cross-dressing:[13]

However, they say that no woman has been caught, except Callipateira only; some, however, give the lady the name of Pherenice and not Callipateira. She, being a widow, disguised herself exactly like a gymnastic trainer, and brought her son to compete at Olympia. Peisirodus, for so her son was called, was victorious, and Callipateira, as she was jumping over the enclosure in which they keep the trainers shut up, bared her person. So her sex was discovered, but they let her go unpunished out of respect for her father, her brothers and her son, all of whom had been victorious at Olympia. But a law was passed that for the future trainers should strip before entering the arena.

We cannot know whether other women also gained admission by cross-dressing in order to watch their sons compete. Women, however, could compete as chariot owners and horse trainers. In his history of the Games Pausanias tells of Belistiche:[14]

Afterwards they added races for chariots and pairs of foals, and for single foals with rider. It is said that the victors proclaimed were: for the chariot and pair, Belistiche, a woman from the seaboard of Macedonia; for the ridden race, Tlepolemus of Lycia.

The most famous competitor, though, was the Spartan Cynisca, already mentioned in H and Gorgo’s Blogpost.[15] Pausanias described her victory:[16]

Archidamus had also a daughter, whose name was Cynisca; she was exceedingly ambitious to succeed at the Olympic games, and was the first woman to breed horses and the first to win an Olympic victory. After Cynisca other women, especially women of Lacedaemon, have won Olympic victories, but none of them was more distinguished for their victories than she.

In her time Cynisca must have been famous, for Pausanias described statues of her in Olympia, next to the temple of Hera, and in her native Sparta.[17]

Nevertheless, in spite of owning her chariot, Cynisca was not allowed to watch the Games. We do know, however, that at least one woman could watch legitimately:

Now the stadium is an embankment of earth, and on it is a seat for the presidents of the games. Opposite the umpires is an altar of white marble; seated on this altar a woman looks on at the Olympic games, the priestess of Demeter Chamyne, which office the Eleans bestow from time to time on different women.[18]

Pausanias immediately goes on to say:

Maidens are not debarred from looking on at the games.[19]

This is an ambiguous statement, contradicting Pausanias’ previous assertion that women watched the Games on pain of death. Whatever the truth of the matter, and perhaps inspired by Cynisca and the mythical sporting women described earlier, Athenian women established their own games, known as the Heraean Games, and described, again, by Pausanias.[20]This is a long extract, but it is a basis for a wider analysis of the meaning of the Heraean games.

Every fourth year there is woven for Hera a robe by the Sixteen women, and the same also hold games called Heraea. The games consist of foot-races for maidens. These are not all of the same age. The first to run are the youngest; after them come the next in age, and the last to run are the oldest of the maidens. They run in the following way: their hair hangs down, a tunic reaches to a little above the knee, and they bare the right shoulder as far as the breast. These too have the Olympic stadium reserved for their games, but the course of the stadium is shortened for them by about one-sixth of its length. To the winning maidens they give crowns of olive and a portion of the cow sacrificed to Hera. They may also dedicate statues with their names inscribed upon them. Those who administer to the Sixteen are, like the presidents of the games, married women. The games of the maidens too are traced back to ancient times; they say that, out of gratitude to Hera for her marriage with Pelops, Hippodameia assembled the Sixteen Women, and with them inaugurated the Heraea. They relate too that a victory was won by Chloris, the only surviving daughter of the house of Amphion, though with her they say survived one of her brothers. As to the children of Niobe, what I myself chanced to learn about them I have set forth in my account of Argos. Besides the account already given they tell another story about the Sixteen Women as follows. Damophon, it is said, when tyrant of Pisa did much grievous harm to the Eleans. But when he died, since the people of Pisa refused to participate as a people in their tyrant’s sins, and the Eleans too became quite ready to lay aside their grievances, they chose a woman from each of the sixteen cities of Elis still inhabited at that time to settle their differences, this woman to be the oldest, the most noble, and the most esteemed of all the women. The cities from which they chose the women were Elis, … The women from these cities made peace between Pisa and Elis. Later on they were entrusted with the management of the Heraean games, and with the weaving of the robe for Hera. The Sixteen Women also arrange two choral dances, one called that of Physcoa and the other that of Hippodameia. This Physcoa they say came from Elis in the Hollow, and the name of the parish where she lived was Orthia. She mated they say with Dionysus, and bore him a son called Narcaeus. When he grew up he made war against the neighboring folk, and rose to great power, setting up moreover a sanctuary of Athena surnamed Narcaea. They say too that Narcaeus and Physcoa were the first to pay worship to Dionysus. So various honors are paid to Physcoa, especially that of the choral dance, named after her and managed by the Sixteen Women. The Eleans still adhere to the other ancient customs, even though some of the cities have been destroyed. For they are now divided into eight tribes, and they choose two women from each. Whatever ritual it is the duty of either the Sixteen Women or the Elean umpires to perform, they do not perform before they have purified themselves with a pig meet for purification and with water. Their purification takes place at the spring Piera. You reach this spring as you go along the flat road from Olympia to Elis.

A number of themes emerge from this extract. First, of course, there are the Heraean Games themselves: if women were excluded from the men’s games, they established their own.

Second, Pausanias seems to be very aware of the sexual status of the women. Maidens are clearly distinguished from married women, perhaps echoed by the latter competing with loose hair, and the two groups had different roles. This echoes Pausanias’ comment quoted earlier that maidens could watch the games. The significance of this escapes me, but it is a theme worth noting.

Third, the women who organised these Games were chosen for diplomatic initiatives. Elis and Pisa were both in western Peloponnese, near Olympia. Perhaps these women were chosen because their management skills were evident in the organisation of the Games. Or perhaps this echoes the famed Olympic Truce that operated during the men’s games, and games in general were seen as opportunities to work for peace.

Finally, the Pausanias extract illustrates how the Games connected with dance and religious ritual, in this case in celebration of the god Bacchus, who was a god associated with groups of women celebrants, perhaps most notoriously in Euripides’ The Bacchae. Here, though, women’s religious activities were seen as positive.

It is also noticeable that none of the women we have studied were from Athens. They were mostly from Sparta or what is now western Greece. When we think of athletic women in ancient times, though, we often think first of Amazons. Adrienne Mayor’s book about them returns us to the theme of a contest to decide a husband. She writes of Atalanta:[21]

Atalanta’s wedding challenge was shocking in a Greek context, but vigorous young women setting athletic contests for potential suitors is a ubiquitous theme in Caucasian, Persian and steppe nomad traditions.

Mayor went on to give examples, first from Aelian quoting Diodorus:[22]

The natural historian Aelian described courtship and marriage among the Saka (Massagetae) as a mock battle for dominance. “If a man wants to marry a maiden, he must fight a duel with her. They fight to win but not to the death. If the girl wins, she carries him off as captive and has power and control over him, but if she is defeated then she is under his control.”

Mayor also tells of a late, thirteenth century CE, woman Aijaruc, a descendant of Ghengis Khan,[23] who wrestled a suitor and defeated him. She was ‘[a] tall, powerfully muscled young woman [who] excelled in horse riding, archery and combat.’

Herodotus quotes Amazons describing their own physical activities, one of the rare occasions where women are presented as speaking for themselves. In this account they are trying to establish diplomatic and sexual relationships with Scythians:[24]

[T]he men said to the Amazons, “We have parents and possessions; therefore, let us no longer live as we do, but return to our people and be with them; and we will still have you, and no others, for our wives.” To this the women replied: “We could not live with your women; for we and they do not have the same customs. We shoot the bow and throw the javelin and ride, but have never learned women’s work; and your women do none of the things of which we speak, but stay in their wagons and do women’s work, and do not go out hunting or anywhere else.”

Spartan women, too, were expected to carry out physical activity. Plutarch wrote of some of the laws that were established by Sparta’s ancient law giver, Lycurgis:[25]

He made the maidens exercise their bodies in running, wrestling, casting the discus, and hurling the javelin, in order that the fruit of their wombs might have vigorous root in vigorous bodies and come to better maturity, and that they themselves might come with vigour to the fulness of their times, and struggle successfully and easily with the pangs of child-birth. He freed them from softness and delicacy and all effeminacy by accustoming the maidens no less than the youths to wear tunics only in processions, and at certain festivals to dance and sing when the young men were present as spectators.

In classical times, though, this physical freedom was seen as shameful and associated with sexual autonomy. In Andromache, Euripides has Peleus say to Menelaus:[26]

You lost your wife to a Phrygian by leaving your house unguarded, believing you had a chaste wife in your house, when in fact she was an utter whore. Not even if she wanted to could a Spartan woman be chaste. They leave their houses in the company of young men, thighs showing bare through their revealing garments, and in a manner I cannot endure they share the same running-tracks and wrestling-places.

We cannot know whose attitude this represented. It may have been that Euripides saw this as associated only with his dramatic reconstruction of Peleus, or it may have reflected Euripides’ own attitude to women or Spartans, or an attitude that was common at the time.

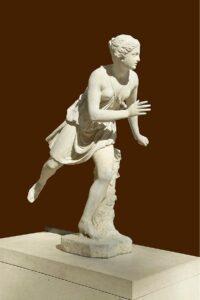

Perhaps the most famous Spartan woman athlete was this one:

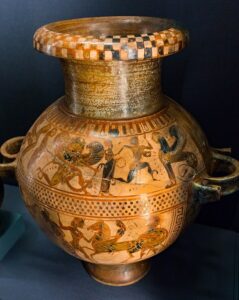

This woman is dressed in the way Pausanias described sportswomen as dressing, and she is in what I have come to call the bent leg pose. Whenever men are in this pose they are described as running.[27] However, doubt is cast on this woman, and some writers suggest she is dancing. Other pictures of women in the bent leg pose include Polyxena, who was killed by Achilles, and, my favourites, because they look so mischievous, the Gorgon from the Museum in Corfu and the Goddess Eris, who threw the apple that initiated the Judgement of Paris and eventually the Trojan War. Mischief indeed.

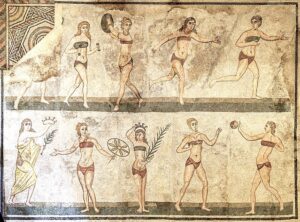

After classical times, and moving into Hellenistic times, women’s physical activity became more evident, as depicted in this wall painting from Sicily.

Pomeroy commented:[28]

[W]omen in Greece did not personally participate in athletic competitions until the first century A.D., when their names begin to appear in inscriptions. An inscription erected at Delphi honouring three female athletes from Tralles proclaims that one of them, Hedea, won prizes for singing and accompanying herself on the cithara at Athens, for footracing at Nelea and for driving a war chariot at Isthmia.

It is easy to dismiss women’s sporting activity in ancient times, because it is often said that they did not participate in the Olympic Games. This is partly true, although, as we have seen, ambiguous. And there were other games. In mythical times, women were hunters and athletes, as well as being prizes for men’s athletic competitions. Mythical women like Atalanta and Cyrene may have provided role models for real women who found creative, and sometimes illicit, ways to engage in sporting activity, and who can be found in a close reading of the sources, and in visual sources too. The pattern was varied, with women’s physical activity in classical Athens being little recorded. However, study reveals some activity both in classical society and elsewhere, particularly in Sparta and the areas where Amazon women lived. As time went on, evidence of activity increased in the Hellenistic period. It is easy to believe that women did little when men did so much, but a little research leads us to question this conclusion, and perhaps to look again.

Image Credits

Atalanta: Pierre Lapautre. Atalanta. Roman copy after Hellenistic original. Louvre Museum. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Atalante_1_Lepautre_Louvre_MR_1804.jpg. License: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/en:Creative_Commons

Cyrene: Cyrene. Museum of Lambaesis, Algeria. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mosaic_of_Apollo_and_the_nymph_Cyrene,_from_Lambaesis,_2nd_or_3rd_century_AD,_Museum_of_Lambaesis,_Algeria_-_52565980629.jpg. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic

Snake Goddess: Snake goddess from the palace at Knossos. https://commons.m.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Snake_Goddess

Temple of Hera: Author’s own.

Bronze figure of Spartan running girl 520-500 BCE: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Spartan_running_girl.jpg. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Achilles pursuing Polyxena: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Archippe_Painter_-_ABV_106_-_Gorgo_pursuing_Perseus_-_Achilles_ambushing_Polyxena_and_Troilos_-_Wien_KHM_AS_IV_3614_-_06.jpg. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Gorgon from west pediment from the temple of Artemis, Corfu: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=gorgon+corfu+museum&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

Eris: commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eris_Antikensammlung_Berlin_F1775.jpg. This work is in the public domain in its country of origin and other countries and areas where the copyright term is the author’s life plus 100 years or fewer

Wall painting. https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?search=villa+romana+del+casale+women+&title=Special:MediaSearch&go=Go&type=image. License: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0

Related Topics

H. and Gorgo, Olympic Games in Ancient Greece. kosmossociety.org/olympic-games-in-ancient-greece/

Q. Olympic games. kosmossociety.org/olympic-games/

Scott, S. Gallery: athletes in action. kosmossociety.org/gallery-athletes-in-action/

Scott, S. Olympic fame. kosmossociety.org/olympic-fame/

Notes

[1] Ϙ. Olympic games. kosmossociety.org/olympic-games/

[2] Apollodorus, Library of Greek Mythology 3,9,2. Available at Perseus.

[3] Pindar, Pythian Odes ix.5. Available at Perseus.

[4] Christensen, J. 2023. The Kind of Monster Story We Need: Cyrene the Lion-Slayer. https://sententiaeantiquae.com/2023/10/24/the-kind-of-monster-story-we-need-cyrene-the-lion-slayer-4/

[5] Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams. Lycophron. Aratus. Translated by Mair, A. W. & G. R. Loeb Classical Library Volume 129. London: William Heinemann, 1921. https://www.theoi.com/Text/CallimachusHymns1.html .

[6] Homer. The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. 23. 259. Available at Perseus.

[7] Homer. Iliad. 23. 700. Available at Perseus.

[8] H. and Gorgo, Olympic Games in Ancient Greece. kosmossociety.org/olympic-games-in-ancient-greece/

[9] https://www.grunge.com/1180844/the-bull-leaping-women-of-ancient-minoan-greece/.

[10] Scott, S. Olympic Fame. kosmossociety.org/olympic-fame/

[11] Pausanias. Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. Available at Perseus.

[12] Pausanias op. cit. 5.6.7.

[13] Pausanias op. cit. 5.6.7.

[14] Pausanias op. cit. 5 8 11.

[15] H and Gorgo op. cit.

[16] Pausanias op. cit. 3 8 1.

[17] Pausanias op. cit. 5 12 5, 6 1 6 and 3 15 1.

[18] Pausanias op. cit. 6 20 9.

[19] Pausanias op. cit. 6 20 9.

[20] Pausanias op. cit. 5 16.

[21] Mayor, A. 2014. The Amazons: lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton University press, Princeton, New Jersey. P. 9.

[22] Mayor op.cit. P. 132.

[23] Mayor op.cit. 402.

[24] Herodotus, The Histories. 4 114 2,3 with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge, Mass. 1922 & reprints. Available at Perseus.

[25] Plutarch, Lycurgus, with an English translation by Bernadotte Perrin, Cambridge, Mass, 1914 and reprints 14 2 Available at Perseus.

[26] Euripides, Andromache. David Kovacs, Ed. 591. Available at Perseus.

[27] See Scott, S. Gallery: athletes in action. kosmossociety.org/gallery-athletes-in-action/

[28] Pomeroy, S.B. 1975. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: women in classical antiquity. London. Bodley Head. 137.

Harlemswife is a member of Kosmos Society