Water is best, and gold, like a blazing fire in the night, stands out supreme of all lordly wealth. But if, my heart, you wish to sing of contests, [5] look no further for any star warmer than the sun, shining by day through the lonely sky, and let us not proclaim any contest greater than Olympia.

Pindar, Olympian 1, 1–7, translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien[1]

The ancient Olympic Games of Greece provided the inspiration for the modern Olympics. I wondered what sort of things the ancient Greek authors said about the games and the athletes who competed in them, and whether that could tell us anything about their attitudes.

The individual winners of events were celebrated back in their home towns. Among the poems of Pindar and Bacchylides are epinikea (victory odes) celebrating those who won victories at the Olympic Games.

In the ‘Introductory Essays’ to his edition of Pindar’s poems, Gildersleeve says:

Herakles is hardly less vividly present to our mind at the Olympian games than Zeus himself. Indeed the Herakles of Pindar might well claim a separate chapter. And as the games are a part of the worship of the gods, so victory is a token of their favor, and the epinikion becomes a hymn of thanksgiving to the god, an exaltation of the deity or of some favorite hero. The god, the hero, is often the centre of some myth that occupies the bulk of the poem…. The myth is often a parallel, often a prototype. Then the scene of the victory is sacred. Its beauties and its fortunes are unfailing sources of song.[2]

In the odes, Pindar provides the names of the victors and the event. Pindar’s ode Olympian 1 celebrates Hieron of Syracuse who won in the horse race, and we also learn the name of his horse, Pherenikos (line 18): a name which appropriately means ‘Victory Bringer’ or ‘carrying off victory’.[3] Bacchylides celebrated the same event in his epinician Ode 5, and also names the horse, which he further describes as “chestnut” [xanthothrix] (line 37)/ [4]

As well as Pindar and Bacchylides, other authors mention Olympic victors, for example:

[The Athenians] marched out to Marathon, with ten generals leading them. The tenth was Miltiades, and it had befallen his father Cimon son of Stesagoras to be banished from Athens by Pisistratus son of Hippocrates. [2] While in exile he happened to take the Olympic prize in the four-horse chariot, and by taking this victory he won the same prize as his half-brother Miltiades. At the next Olympic games he won with the same horses but permitted Pisistratus to be proclaimed victor, and by resigning the victory to him he came back from exile to his own property under truce. [3] After taking yet another Olympic prize with the same horses, he happened to be murdered by Pisistratus’ sons, since Pisistratus was no longer living. They murdered him by placing men in ambush at night near the town-hall. Cimon was buried in front of the city, across the road called “Through the Hollow”, and buried opposite him are the mares who won the three Olympic prizes.

Herodotus The Histories 6.103.1–3, translated by Godley[5]

Unlike Pindar and Bacchylides, Herodotus does not mention the names of these horses, but such animals must have been revered to have received such a prominent burial place.

Pausanias mentions seeing a statue of a successful boxer, and a bronze head has been found which may be from that very statue:

Satyros of Elis, son of Lysianax, of the clan of the Iamidai, won five victories at Nemeā for boxing, two at Pythō, and two at Olympia. The artist who made the statue was Silanion, an Athenian.

Pausanias Description of Greece 6.4.5, translated by Jones/Nagy[6]

Victory was associated not only with the successful competitor, but also with his home city, as we saw with the odes of Pindar and Bacchylides. Herodotus gives another example:

Demaratus reached Asia through such chances, a man who had gained much renown in Lacedaemon by his many achievements and his wisdom, and by conferring on the state the victory in a chariot-race he had won at Olympia; he was the only king of Sparta who did this.

Herodotus The Histories 6.70.3, translated by Godley[7]

Given the mythological association of Sparta with Castor and Polydeukes, who were known as horsemen[8], it is surprising that in real life, at least during the time of the Olympics, only one king of Sparta was successful in the chariot racing!

The Wikipedia article on Pindar [9] lists the odes in chronological order with approximate dates of composition. These are the Olympic victories mentioned in the list:

- 488 (?) Olympian 14: Asopichus of Orchomenus in the Boys’ foot-race

- 476 Olympian 1: Hieron of Syracuse in the Horse-race

- 476 Olympians 2 & 3: Theron of Acragas in the Chariot-race

- 476 Olympian 11: Agesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris in the Boys’ Boxing Match

- 474 (?) Olympian 10: Agesidamus of Epizephyrian Locris in the Boys’ Boxing Match

- 468 Olympian 6: Agesias of Syracuse in the Chariot-race with mules

- 466 Olympian 9: Epharmus of Opous in the Wrestling-Match

- 466 Olympian 12: Ergoteles of Himera in the Long foot-race

- 464 Olympian 7: Diagoras of Rhodes in the Boxing-Match

- 464 Olympian 13: Xenophon of Corinth in the Short foot-race & pentathlon

- 460 Olympian 8: Alcimidas of Aegina in the Boys’ Wrestling-Match

- 460 or 456 (?) Olympian 4 & 5: Psaumis of Camarina in the Chariot-race with mules

From these dates it appears that the poems may not all have been composed at the time of the victories: the Wikipedia article on “Ancient Olympic Games” says the contests were held every four years.[10] The article also mentions that the Olympiad “became a unit of time in historical chronologies.”

There are many examples of this method of referring to the Olympic Games as a point in time for dating other events, such as:

Calliades was archon in Athens, and the Romans made Spurius Cassius and Proculus Verginius Tricostus consuls, and the Eleians celebrated the Seventy-fifth Olympiad, that in which Astylus of Syracuse won the “stadion.”

Diodorus Siculus 11.1.2, translated by Oldfather[11]

When Phaedon was archon in Athens, the Seventy-sixth Olympiad was celebrated, that in which Scamandrus of Mytilenê won the “stadion,” and in Rome the consuls were Caeso Fabius and Spurius Furius Menellaeus.

Diodorus Siculus 11.48.1, translated by Oldfather[12]

He [=Plato] was succeeded by Speusippus, an Athenian and son of Eurymedon, who belonged to the deme of Myrrhinus, and was the son of Plato’s sister Potone. He was head of the school for eight years beginning in the 108th Olympiad.

Diogenes Laertius Lives of Eminent Philosophers 4.1, translated by Hicks[13]

Hicks’ footnote to this passage says this was 348–344 BCE.

I shall now take up the history of Greece during the same period, ending at the same date, and commencing from the 140th Olympiad.

Polybius Histories 4.1, translated by Shuckburgh[14]

Shuckburgh’s edition shows this as 220–216 BCE.

With all the celebratory odes and kudos to the victors, it is tempting to think that everything was conducted in a fair, sportsman-like way. But even in Iliad 23 in the Funeral Games for Patroklos there were some underhanded tactics:

Presently Antilokhos saw a narrow place where the road had sunk. [420] The ground was broken, for the winter’s rain had gathered and had worn the road so that the whole place was deepened. Menelaos was making towards it so as to get there first, for fear of a foul, but Antilokhos turned his horses out of the way, and followed him a little on one side. [425] The son of Atreus was afraid and shouted out, “Antilokhos, you are driving recklessly; rein in your horses; the road is too narrow here, it will be wider soon, and you can pass me then; if you foul my chariot you may bring both of us to a mischief.”

But Antilokhos plied his whip, [430] and drove faster, as though he had not heard him. They went side by side for about as far as a young man can hurl a disc from his shoulder when he is trying his strength, and then Menelaos’ mares drew behind, for he left off driving [435] for fear the horses should foul one another and upset the chariots; thus, while pressing on in quest of victory, they might both come headlong to the ground. Menelaos then upbraided Antilokhos and said, “There is no greater trickster living than you are; go, and bad luck go with you; [440] the Achaeans say not well that you have understanding, and come what may you shall not bear away the prize [āthlon] without sworn protest on my part.”

Iliad 23.418–441, Sourcebook [15]

In the historical period, Pausanias reports on rule-breaking in the Olympic Games: in the Altis (Elis) he reports:

{5.21.2} As you go to the stadium along the road from the Mētrōon, there is on the left at the base of the mountain [oros] named Kronion a platform of stone, right by the very mountain [oros], with steps through it. By the platform have been set up bronze statues [agalmata] of Zeus. These have been made from the fines inflicted on athletes who have wantonly broken the rules of the contests, and they are called Zanes [figures of Zeus] by the natives.

Pausanias Description of Greece 5.21.1–2, translated by Jones/Nagy[16]

Pausanias goes on to describe why fines were elicited, mainly due to athletes bribing fellow competitors. Here is an example:

{5.21.3}…The first, six in number, were set up in the ninety-eighth Olympiad. For Eupolos of Thessaly bribed the boxers who entered the competition, Agenor the Arcadian and Prytanis of Kyzikos, and with them also Phormion of Halicarnassus, who had won at the preceding Festival. This is said to have been the first time that an athlete violated the rules of the Games, and the first to be fined by the Eleians were Eupolos and those who accepted bribes from Eupolos.

{5.21.4}Except for the third and the fourth, these images have elegiac inscriptions on them. The first of the inscriptions is intended to make plain that an Olympic victory is to be won, not by money, but by swiftness of foot and strength of body. The inscription on the second image declares that the image stands to the glory of the deity, through the piety of the Eleians, and to be a terror to law-breaking athletes. The purport of the inscription on the fifth image is praise of the Eleians, especially for their fining the boxers; that of the sixth and last is that the images are a warning to all the Greeks not to give bribes to obtain an Olympic victory.

Pausanias, Description of Greece 5.21.3–4[17]

In another example, an athlete was found guilty of not bribery, but of not following the rules:

{5.21.12} Afterwards, others were fined by the Eleians, among whom was an Alexandrian boxer at the two hundred and eighteenth Festival. The name of the man fined was Apollonios, with the surname of Rhantes—it is a sort of national characteristic for Alexandrians to have a surname. This man was the first Egyptian to be convicted by the Eleians of a misdemeanor.

{5.21.13} It was not for giving or taking a bribe that he was condemned, but for the following outrageous conduct in connection with the Games. He did not arrive by the prescribed time, and the Eleians, if they followed their rule, had no option but to exclude him from the Games. For his excuse, that he had been kept back among the Cyclades islands by contrary winds, was proved to be an untruth by Hērakleidēs, himself an Alexandrian by birth. He showed that Apollonios was late because he had been picking up some money at the Ionian Games.

Pausanias, Description of Greece 5.21.12–13[18]

Pausanias describes how many of these images carried hortatory inscriptions warning against bribery, but he also describes some victories that were won fairly, where he refers to the Eleian record of Olympic victories:

{5.21.9} … In this record, it is stated that Straton of Alexandria at the hundred and seventy-eighth Festival won on the same day the victory in the pankration and the victory at wrestling. Alexandria on the Canopic mouth of the Nile was founded by Alexander the son of Philip, but it is said that previously there was on the site a small Egyptian town called Rakotis.

{5.21.10} Three competitors before the time of this Straton, and three others after him, are known to have received the wild-olive for winning the pankration and the wrestling: Kapros from Elis itself, and of the Greeks on the other side of the Aegean, Aristomenes of Rhodes and Protophanes of Magnesia on the Lethaios, were earlier than Straton; after him came Marion his compatriot, Aristeas of Stratonikia (anciently both land and city were called Khrysaoris), and the seventh was Nikostratos, from Cilicia on the coast …

Pausanias Description of Greece 5.21.9–10[19]

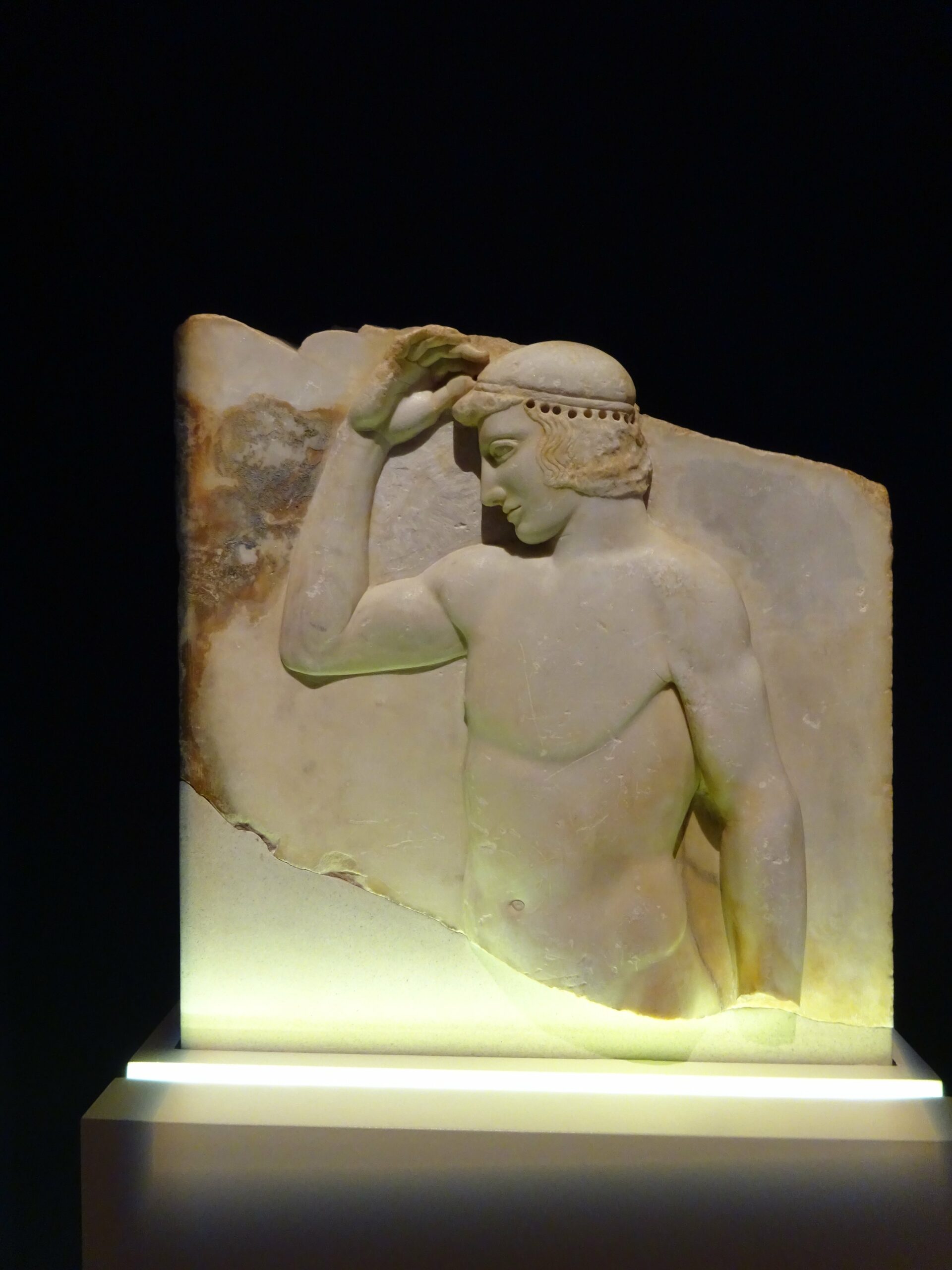

These days Olympic victors are awarded medals, but Pausanias’ mention of “wild-olive” refers to the victory garland that was awarded at Olympia, and there are images of athletes wearing garlands to indicate success.

As I explored these passages and images, I started to ponder on how, after all the training and the contest itself, the moment of victory was fleeting, and the olive leaves would have started to wilt, but the pride in victory must have persisted, and the memorials to the athletes’ success—in songs, prose and artworks—have lasted to this day.

Have you come across examples of how ancient Greek authors referred to the Olympic Games? I invite members to share other passages from ancient Greek authors that refer to athletes, and how they were celebrated by others in poetry, prose, or visual arts.

Related topics

Olympic Games in Ancient Greece

Notes

Texts retrieved May 2024

[1] Odes. Pindar. Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

Online at Perseus.

[2] Gildersleeve: Introductory Essay: ‘Victory odes’ in Pindar: The Olympian and Pythian Odes. Basil L. Gildersleeve. Anne Mahoney. edited for Perseus. New York. Harper and Brothers. 1885.

Online at Perseus.

[3] Entry for φερέ-νικος in Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by. Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus.

[4] Bacchylides. Diane Arnson Svarlien. Odes. 1991.

Online at Perseus.

[5] Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920. Online at Perseus

[6] Pausanias Reader in Progress: Description of Greece, Scrolls 1–10. An ongoing retranslation based on an original translation by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes added by Jones. The retranslation, to date, is by Gregory Nagy.

[7] Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920. Online at Perseus .

[8] Described as such, for example, in the article “Dioscuri” at theoi.com.

[11] Diodorus Siculus. Diodorus of Sicily in Twelve Volumes with an English Translation by C. H. Oldfather. Vol. 4–8. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989.

Online at Perseus.

[13] Diogenes Laertius. Lives of Eminent Philosophers. R.D. Hicks. Cambridge, Mass.. Harvard University Press. 1972 (First published 1925).

Online at Perseus.

[14] Histories. Polybius. Evelyn S. Shuckburgh. translator. London, New York. Macmillan. 1889. Reprint Bloomington 1962.

Online at Perseus

[15] Homeric Iliad, Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at Kosmos Society.

[16] Pausanias Reader in Progress: Description of Greece, Scrolls 1–10 . An ongoing retranslation based on an original translation by W. H. S. Jones, 191 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes added by Jones. The retranslation, to date, is by Gregory Nagy.

Texts retrieved May 2024

Image credits

Hermonax painter: Victory in a chariot, 450–400 BCE .

Photo: Yair-haklai. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license , via Wikimedia Commons.

Head of a boxer, probably of Satyros of Elis by bronze-sculptor Silaniōn, c. 330-320 BCE. From the Sanctuary of Zeus at Olympia.

Photo: Tilemahos Efthimiadis. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license , via Wikimedia Commons.

Relief sculpture Victorious youth dedicating prize to Athena, c. 460 BCE. Archaeological Museum of Athens Photo: Kosmos Society.

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by galleries or museums, or on Wikimedia Commons or Flickr at the time of publication on this website.

Images retrieved May 2024.

___

Sarah Scott is a member of Kosmos Society