In this section we will consider the ships that are described as megakētēs [μεγακήτης], usually translated as huge, hollow, and gaping. The word is made up of two parts, mega [μέγα-, “great”], and an adjective form of kētos [κῆτος, “any sea-monster”]. A related word is kētōeis [κητώεις], which means “full of hollows”.

In a ship’s geometry the epithet describes the threatening form of the forefoot [steira] of the ancient Greek ship. The threat that is transmitted is the idea of being swallowed up by the gaping mouth of a giant fish. Being swallowed by a sea monster is the maritime version of being swallowed up by the earth.[1]

In mythical terms, however, Kētos was a giant fish who lived in the littoral waters off the coast of Jaffa, now part of modern Tel Aviv. There this monster awaits his chance to snatch his easy prey from the beach. By the end of this section you might agree that this yawning monster was not a fish, but a Greek ship raiding the Syro-Caaanite coast.

A traditional story[2] about Kētos (the fish) starts with how lovely queen Cassiopeia boasts that her daughter Andromeda is more beautiful than the Nereids. Of course, she herewith invokes the wrath of Poseidon, and to calm him down, she, Cassiopeia and her husband Cepheus, decide to sacrifice Andromeda and they chain her to a rock near the shore of the sea.

Perseus, incidentally strolling over that same beach that same day, finds the beautiful Andromeda chained to the rock exactly at that same moment when Kētos emerges from the ocean and takes a closer look at Andromeda. The great hero then drives his sword into the back of the monster and kills him. Perseus then marries Andromeda[3], but only after he used Medusa’s head to turn his rival, uncle Phineus, to stone. Their son, Perses, supplies the name of the Persians.[4]

- If, on the other hand, I swim further in search of some shelving beach or harbor, a hurricane may carry me out to sea again sorely against my will, or the gods may send some great monster [kētos] of the deep to attack me; for Amphitrite breeds many such, and I know that Poseidon, the renowned Earth-shaker, is very angry with me.”

Odyssey 5.417, adapted from Sourcebook[6] - And she (Scylla) sits deep within her shady cell thrusting out her heads and peering around the rock, fishing for dolphins [delphis, pl.] or dogfish [kuōn, ] or any larger monster [kētos] that she can catch, of the thousands with which Amphitrite teems.

Odyssey 12.97, adapted from Sourcebook - Arriving there, he (Poseidon) harnessed to his chariot his two bronze-hooved horses —swift they were, with golden manes streaming from their heads— and he put on his golden armor, which enveloped his skin, and he seized his whip, golden it was, beautifully made, and he stepped on the platform of his chariot, and off he went over the waves, and the sea creatures [kētos, pl.] were frolicking underneath as we went along. They came out from all their hiding places down below, recognizing their lord and master.

Iliad 13.23-28, adapted from Sourcebook

In Homeric poetry, there are some occasions where the word megakētēs is used in figurative speech:

- As when fish flee scared before a huge-gaping dolphin [megakētēs] and fill every nook and corner of some fair haven—for he is sure to eat all he can catch—even so did the Trojans cower under the banks of the mighty river.

Iliad 21.22-25, adapted from Sourcebook - The ships went well, for the gods had smoothed the great-mawed [megakētēs] sea.

Odyssey 3.158, adapted from Sourcebook - Our [= Menelaos and friends] ambuscade would have been intolerable, for the stench of the fishy seals was most distressing—who would go to bed with a sea monster [kētēs] if he could help it? —

Odyssey 4.443, adapted from Sourcebook - To this end he [= Agamemnon] went around the ships and tents carrying a great purple cloak and took his stand by the huge [megakētēs] black hull of Odysseus’ ship, which was middlemost of all.

Iliad 8.220–223, adapted from Sourcebook

In this last quote, the authority of Agamemnon is emphasized three times: he wears the purple cloak, he stands next to the threatening hull, and he stands in the central station [messatos] of the narrative, which is near the ships of Odysseus, Agamemnon, Diomedes and Nestor. The ships of Achilles are far to the right, and the ships of Ajax far to the left.[7]

This relative positioning of the ships is also narrated in the next example of the Greek word megakētēs describing a gaping sea monster, kētos [κῆτος].

- And now as Dawn rose from her couch beside haughty Tithonos, harbinger of light alike to mortals and immortals, Zeus sent fierce Discord with the ensign of war in her hands to the fast ships of the Achaeans. She took her stand by the huge [megakētēs] black hull of Odysseus’ ship which was middlemost of all, so that her voice might carry farthest on either side, on the one hand towards the tents of Ajax son of Telamon, and on the other towards those of Achilles—for these two heroes, well-assured of their own strength, had valorously drawn up their ships at the two ends of the line.

Iliad 11.1-5, adapted from Sourcebook

A last example, now stressing the idea of volume and space that goes with megakētēs:

- He [= Nestor] was seen and noted by swift-footed radiant Achilles, who was standing on the spacious [megakētēs] stern [prumnos] of his ship, watching the sheer pain [ponos] and tearful struggle of the fight.

Iliad 11.600–601, adapted from Sourcebook

How can we envisage a ship with a sense of something large swallowing people up? Firstly, we will look at the work of two artists, the Kleimachos potter and the mysterious Aristonothos, who have left their art works for us to enjoy. Both works provide us with ideas on what Homer must have envisaged when he described the ships of Odysseus and Achilles as megakētēs.

On both ship representations, the prow somewhat resembles the gaping snout of a sea monster. The representation of the snout-shaped forefoot, however, occurs not only at these two vases, but also on many other depictions, such as on the François kratēr, as shown in the image below.

The Aristonothos kratēr from Caere

Firstly we will look at the beautiful late-Geometric style kratēr that was found in a tomb in Cerveteri[8], a city on the central west coast of Italy. Originally Cerveteri was the Etruscan city of Caere, a member of the Etruscan dodecapolis[9]. In Greek, Caere was known as Agylla. Based upon the type of clay that the vase is made of, it was concluded that she was manufactured locally in Etruria. The date of manufacture is second quarter of the seventh century; 675–650 BCE.

There are three parts that need to be looked at when trying to understand the story of the vase on the vase:

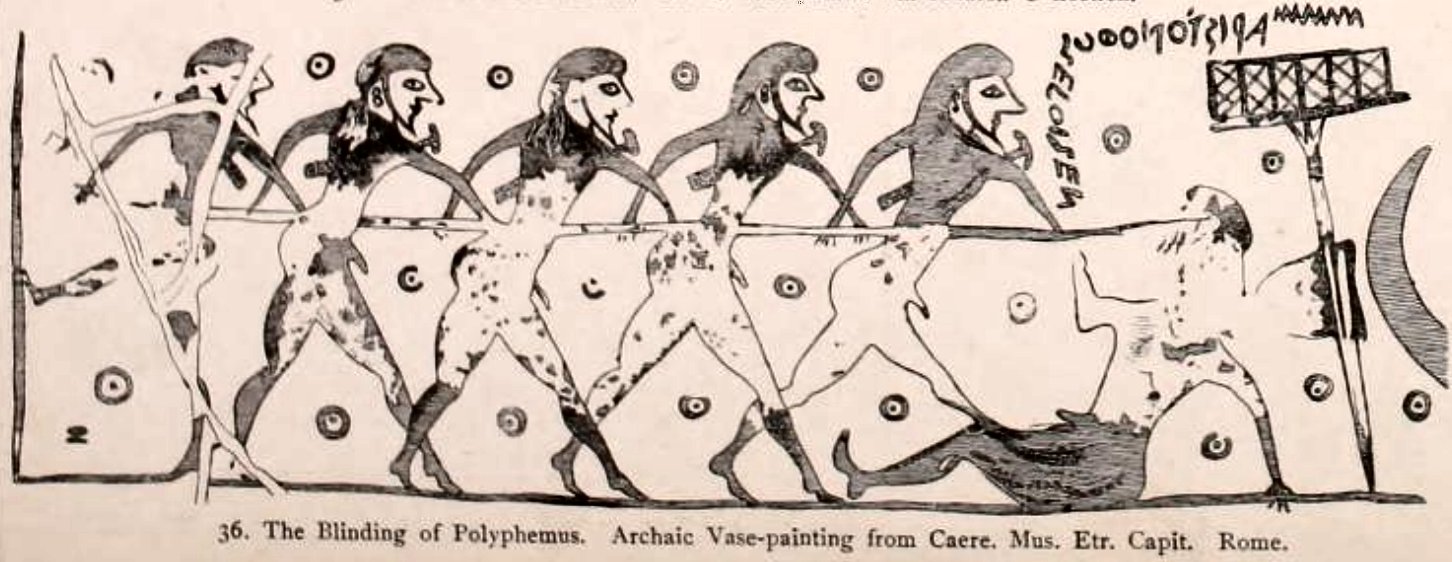

- The front side of the vase, which depicts the story of the blinding of Polyphemus by Odysseusand his four companions.

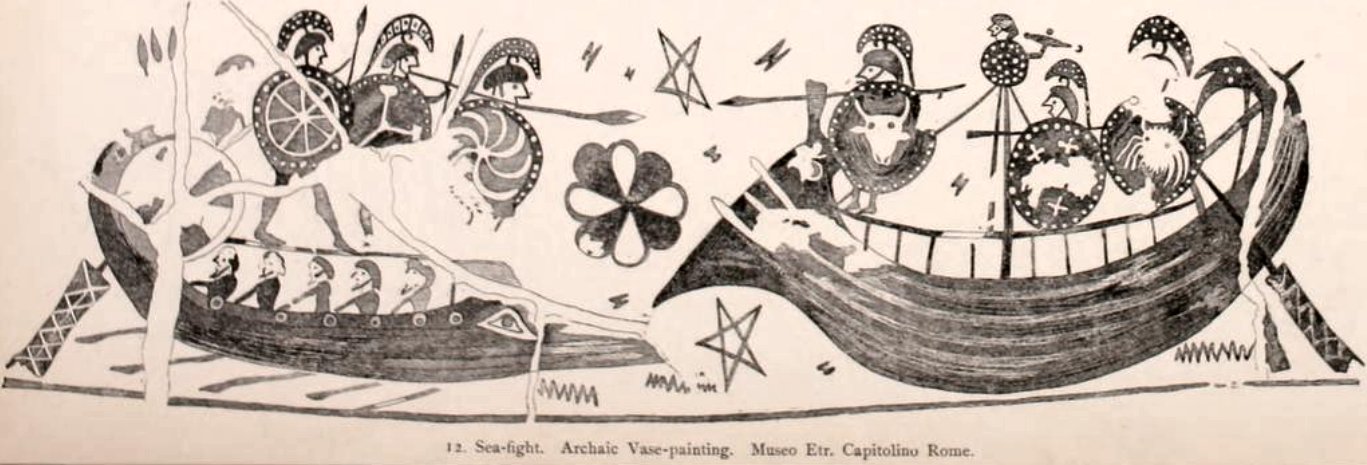

- The back side, which displays a sea raid, in which a threatening hull prepares for the attack on a merchant ship.

- The text on the image, Aristonothos epoisen (“Aristonothos made me”), which at first sight identifies Aristonothos as the maker of this vase.

Both the images are part of one and the same narrative. The first part of the narrative is land-based; the second part is sea-based. Traditionally the narrative is interpreted as that of the early Greek colonist, who must deal both with dangerous natives and with battle at sea.

Not shown on the images is the crab that is depicted under the handles of the crater: symbol of the right use of skill and intelligence [mētis] of which Odysseus is the metaphor. The decoration of the band below the narrative consists of a checkerboard pattern, supported by a band of arrows and sharply pointed triangles.

The context is that in the 7th century Greek colonization was thriving business. Euboean Greeks from Eretria and Chalcis had firstly settled on the island of Ischia, an island at the northern end of the Gulf of Naples. The island was preferred because of its fine harbor and its easy defense against raids from the sea. The island gave home to a mixed population of Greeks, Etruscans, and Phoenicians. The main settlement of the island, named Pithecusae, became the Greek center for trade in iron with the mainland of central Italy. In 700 BCE, the time period that we look at in this discussion, the place gave home to 5,000–10,000 people. By then the colonization of the south of Italy was so intensive that the area was called “Magna Graecia”.[10]

Firstly, we will look at the part of the text that gives us the name of the painter; Aristonothos. A fascinating analysis by Mel Copeland[11], makes it plausible that the name Aristonothos may be decomposed into two parts, which then read: “the best [aristo-] Odysseus [outis]”. In this interpretation Odysseus [outis] is the best [aristos] and becomes the protagonist of the story.

Copeland observes that the place of the text on the vase corresponds with the moment in time of the narrative on which Odysseus, depicted as the most forward in the line of five, replies that he is called “outis”: “No-one,” or “No-name”[12]. Therefore, the name Aristonothos can be read as Nobody [outis] is the best [aristo] (of the Greeks). To add to the confusion, however, Aristonothos, can also be broken down in the usual way [aristo nothos], which means “best bastard”; a contradiction in terms. Can it be that we have run into an Etrurian wordplay?

Next, looking at the image that is land-based, we see the representation of five men, organized in an almost geometrical pattern. Odysseus and his four companions are caught in the act of blinding Polyphemus, who, remarkably, is not larger than his attacker. The men carry a sword over their shoulder.

The Greek companion that is most to the left, pushes his leg against the wall, which is also the frame of the image, to add to the force with which the eye of the skinny shepherd [poimēn] is penetrated. Behind Polyphemus, on a stick, is his cheese-rack loaded with cheeses.[13]

Lastly, we look at the back-side image, of which the narrative is sea-based, the approach to a sea raid. To the left we see an open ship [áphraktos; unfenced, undefended], long and narrow in appearance. The forefoot [steira] of this long-ship [nḗus makra] has the threatening shape of a sea monster [megakētēs]. Three marine combatants [epibates] stand on a deck of which the artist has taken the aspectal liberty to draw it above the heads of the five oarsmen, their spears ready for throwing. A helmsman [kubernētēs] operates the stern quarter rudder [pēdalion].

The ship to the right is a sail driven merchantman, probably Etruscan[14]. The voluminous contour of the stem of the ship curves forward. Does it end in the shape of an umbel? The stern post curves inward and has a forward bending decoration. The three marines on deck are ready to defend the ship. Two of them, however, remain tactically on the aft ship and another has taken position in the top of the mast. The mast is stayed with single stays towards fore and aft.

This Etrurian vase holds a fascinating story—told by two paratactic images and a play with words—told in many merry drinking party [sumposion][15] —but for us just to guess. I could subscribe to the opinion that Etruscan thalassocrats of Caere flagged that it takes five Greek colonists to kill a harmless native Etrurian shepherd. In any case, Odysseus remains the metonym for the early Greek colonist, for the better and the worse.

The Athenian vase by the Kleimachos potter

Another example of this fascinating ship, idealized with the snout of a sea monster, is shown graphically on the shoulder of an Athenian Hydria[16] that is attributed to the Kleimachos potter (575–525 BCE). The inscription of the vase says “Kleimachos made me and I am his” [eimὶ keίnou], which we take note of.

The represented ship is manned by oarsmen which are arranged in two rows [stoikhoi], their sides protected by shields. The oars, ten each side, double the number of heads and shields: five each side. The prow is detailed enough to give some idea about the construction: the oars stick out of the hull just below the highest row of planks. The red-eye is winking wickedly. The prow resembles the shape of a gaping sea monster. Is this what Homeric poetry describes when it talks about the ships that are huge, hollow and swallowing [megakētēs]?

A steersman [kubernētēs, steersman] and a navigator [prōratēs, or prōreus, fore-looker] are depicted respectively at the stern and the prow of the ship. The sitting steersman operates a double-oar [pēdalion] for steering the ship. Behind the steersman, the stern-ornament [decorated aphlaston]: a swan’s head and two flowers. The navigator holds a pole and is ready to sound the water depth when the ship closes in to the shore. The drummer [keleustēs, orderer] stands in the middle of the boat, beating the drum to support the rhythm of the rowers.

The decoration on the body of the vase is disturbing: two warriors kicking a defeated opponent, their spears ready to kill him, he is lying on the ground. Youths with spears, draped in long robes, are bystanders in this stylized, silenced, moment of violence.

Notes

[1] Compare: “For as Jonah was three days and three nights in the belly of a huge fish [κήτους], so the Son of Man will be three days and three nights in the heart of the earth.” Gospel of Matthew 12:40

[2] For example, as recounted in Apollodorus Bibliotheca 2.43–44

[3] Within Greek myth it is fully acceptable that Perseus, the great-grandfather of Heracles, marries the granddaughter of Belus, who is Heracles’ grandson.

[4] “When Perseus son of Danae and Zeus had come to Cepheus son of Belus and married his daughter Andromeda, a son was born to him whom he called Perses, and he left him there; for Cepheus had no male offspring; it was from this Perses that the Persians took their name.” Herodotus. Histories, 7.61

[5] Antike korinthische Vase mit Darstellung von Perseus, Andromeda und Ketos. Antikensammlung, Altes Museum (Berlin).

[6] Sourcebook The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2018.12.12. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

[7] Homeric Iliad 24.27–36.

[8] The vase is kept in Rome, Musei Capitolini, Collection Castellani 172.

[9] Dodecapolis: the twelve cities of the Etruscan civilization.

[10] Derived from Jonathan M. Hall, A History of the Archaic Greek World, ca. 1200-479 BCE

[11] Mel Copeland, 2015. The Fascinating Etruscan Kratēr of Aristonothos

[12] Remember that, as recounted in Odyssey 9, when the drunk Polyphemus asks Odysseus to tell his name, Odysseus tells him “outis,” which means “nobody.” When Polyphemus, after he is blinded, calls for help, saying that “Nobody” has hurt him, his fellow giants recommend prayer as the answer.

[13] “We soon reached his cave, but he was out shepherding, so we went inside and took stock of all that we could see. His cheese-racks were loaded with cheeses, and he had more lambs and kids than his pens could hold.” Homeric Odyssey 9.216-219

[14] Compare the Etruscan merchantman on a 6th-century vase from Vulci, British Museum, BM H 230.

[15] The kratēr was used for mixing wine.

[16] Athenian black-figure vase by the Kleimachos potter, vase number 300789, Paris, Musée du Louvre, E735.

Bibliography

Casson Lionel. 2014. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. Available online at Project MUSE, Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore.

Copeland, Mel. 2015 The Fascinating Etruscan Kratēr of Aristonothos.

https://www.academia.edu/12476293/The_Fascinating_Etruscan_Aristonothos_Krater

Delivorrias, A. ea. 1987. Griekenland en de zee. Ministry of Culture of Greece

Homeric Iliad. Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray. Published under a Creative Commons License 3.0.

Homeric Odyssey. Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray. Published under a Creative Commons License 3.0.

Morrison, J. S.; Coates, J. F. ; Rankov, N. B. 1986. The Athenian Trireme: The History and Reconstruction of an Ancient Greek Warship. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

Kirk, G. S. 1949. “Ships on Geometric Vases.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 44: 93–153. doi:10.1017/S0068245400017196.

Wachsmann, Shelly. 2008. Seagoing Ships and Seamanship in the Bronze Age Levant. Ed Rachal Foundation Nautical Archaeology Series. Texas A&M University Press. College Station, Texas.

Image credits

Figure 1: Amphora depicting Perseus rescuing Andromeda from Ketos, Antikensammlung, Altes Museum (Berlin). Montrealais (photo).

Creative Commons CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 2: Detail from Ship representation on the François kratēr, with snout-shaped forefoot. National Archaeological Museum of Florence. Sailko (photo), Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: Der sogenannte Aristonothos-Krater aus Caere. Angefertigt im 7. Jahrhundert v. Chr. Author Rabax63. licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Front: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AristonothusKrater1.jpg

Back: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:AristonothusKrater2.jpg

Figure 4: from “Odyssey Plate VI.” Engelmann, R; Anderson, W.C.F. 1892. Pictorial Atlas to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, London, H. Grevel & Co. via archive.org

Figure 5: from “Odyssey Plate III” Engelmann, R; Anderson, W.C.F. 1892. Pictorial Atlas to Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, London, H. Grevel & Co. via archive.org

Figure 6: Egisto Sani ‘Traveling by sea – III’ Attic black-figure hydria, attributed to the Kleimachos Potter, c 575–525 BCE, Louvre. Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, via Flickr

___

Rien is a participant of the Kosmos Society.

First Published February 28. 2019