Introduction, Translation, and Notes by Jack Vaughan

Introduction

Pindar’s second Pythian Ode, as the poem has come down to us arranged in a book of “Pythians” is the second of three odes addressed to Hieron, who was the ruler of Syracuse after the death of his brother Gelon in 478 BCE and until his own death in 466. The poem is in four strophes (marked, as in Greek editions, Α’, Β’, Γ’, Δ’) in mostly Aeolic mixed with iambic meters.

While Hieron had won victories with his four-horsed chariot teams at the Olympic and Pythian games and doubtless other, less prestigious victories, Pythian 2 does not clearly identify a specific contest or site of the victory immortalized in Pindar’s magnificent poetry here, which may be intended as a portrait of Hieron winning chariot races as one of his numerous accomplishments celebrated in Pythian 2. Much like Pythian 3, which refers to Hieron’s victorious racehorse Pherenikos but is essentially a poem of consolation, counsel, and concern for an ailing friend, Pythian 2 is well placed in the book with Pythian 1, which celebrates a Pythian victory at Delphi in 470, but P.2 weaves into the canvas a wider range of Hieron’s virtues and accomplishments, and delivers deeply personal messages concerning issues of importance both to the poet and to the real addressee, the person Hieron. The messages are wrapped in myth and metaphor, which is frequently Pindar’s way of delivering messages on difficult subjects tactfully and with reverence. In so doing, the poet effaces himself, compliments others without sinking into fulsome praise, and criticizes without acrimony.

We may note, as others have noted, that the arrangement of Pindar’s Epinikia, displays a number of guiding principles the Ancient editors seem to have followed, including placing most ambitious and in some important respect or respects more distinguished poems toward the front of the books of Olympian, Pythian, Isthmian, and Nemean Odes. This is more apparent in the cases of the Olympian and Pythian collections which include some shorter, less ambitious poems interspersed with greater ones after the first several poems that are monumental. The book of Pythians opens with three major poems addressed to Hieron, followed by two poems addressed to Arkesilaos, king of Cyrene, the first of which is Pindar’s longest surviving poem, his (the earliest surviving) version of the Argonaut saga. After these first five fine poems addressed to kings, the magnificent P.6 addressed to Xenokrates of Akragas, followed by a short victory ode to Megakles of Athens sets up a pattern of interspersing less ambitious poems with the major poems.

Translation

Pindar, Pythian 2

For Hieron, victor in Chariot Race

A´ O great city of cities, sacred

precinct of profound war god Ares, Syracuse, divine nurturer of men and

horses that delight in steel, to you I travel from rich Thebes

carrying in herald’s song report of the finely crafted

earth-shaking four-horsed chariot in which

Hieron, defeating the competitors,

crowned Ortygia with victory garlands of far-reaching splendor,

Ortygia the seat of river-haunting Artemis, without whom

he would not have controlled those racing mares fitted with multicolored

reins in his firm gentle hands.

For the maiden goddess who lets fly showers of arrows grants with both hands

—together with Hermes, divine ruler of games,—

Hieron the supreme honor of victory

when for his well-crafted car he yokes together powerful horses to horse-governing chariot reins, while he invokes the widely powerful trident-wielding god.

One man accomplishes for some, another man for others a hymn sweet sounding to kings as a reward of excellence.

[15] Songs of the Cypriots often resound in praise about Kinyras,

Aphrodite’s cherished priest whom golden-haired Apollo loved as a friend.

Respectful gratitude for friends’ deeds leads from one thing to something else.

Oh son of Deinomenes, a maiden before her home in Epizephyrian Locris sings your praise, as she sees her city safe from attack of irresistible enemies, thanks to your power.

They say that by commands of gods Ixion says these things to mortals as he is rolled everywhere on a winged wheel: “Go see your benefactor and repay him with gentle recompense.”

B’ [25] He learned that clearly. For having seized a sweet life of luxury among the kindly disposed children of Kronos, he did not long endure blessed happiness, when with insane mind he fell in love with Hera, whom the happy beds of Zeus had won, but overweening pride propelled Ixion to arrogant folly and ruin.

[30] Soon suffering fittingly, he was severely punished. His two sins brought him pain: first that the hero for the first time brought domestic murder to mortals not without a devious invention, and that once in the god’s cavernous bedrooms he made an attempt on the god’s wife.

According to one’s own true self and ways, everyone must observe moderation.

[35] Illicit beds throw mortals into total wickedness. It caught up also with Ixion: after chasing a sweet deception the ignorant man lay with a cloud. For brilliantly conspicuous in form appeared the daughter of Kronos, the highest of the celestial goddesses, but it was a bait, set by the skillful hands of Zeus, fine contrivance of pain, the four-spoked wheel of bondage that the god made for Ixion’s ruin. After falling into inescapable fetters binding his limbs to the wheel, he accepted the universal message he proclaims.[1] Without the graces the cloud, alone, gave birth to a single male son who brought honor neither to men nor to the laws of the gods. Rearing him she called him Centaurus. He mated with mares of Magnesia in the foothills of Mount Pelion, whence the birth of an amazing herd, resembling in part both parents, down below the mother mare, above the father.

Γ´ A god accomplishes all goals on divine wishes,

[50] a god, who catches the winged eagle and outstrips the sea dolphin,

and humbles any arrogant mortal, but confers glory on others that does not age. As for me, there is need to avoid and escape the violent bite of abuse and belittlement. Although at a distance I often saw reproachful Archilochus unable to help himself, puffed up in hatred vented in bitter words. Wealth with fortune of the fate of wisdom is best.

But you are able to show him to a free mind, sovereign lord of many beautifully garlanded streets and a great people. And if someone says that in possessions and honor some other person [60] in Hellas previously was superior, he fights with a hollow mind vainly. But I will mount a well-decorated ship’s rostrum, singing for all to hear your excellence.

Boldness helps youth in the dangers of war. For that I say that you will find unbounded renown [65] both fighting and competing among horse-driving men, and in infantry battles. More age-seasoned counsels allow me, a word safe to say, to praise you on every account. Hail!

This song is shipped as Phoenician ware over the grey sea. View kindly the Castor’s song[2] for Aeolian strings as you meet the grace of the seven-tone lyre. Having learned and learning, become who you are.[3] Among children a monkey is fine, always

Δ´ fine. But Rhadamanthys did well because he acquired the irreproachable fruit of a wonderful mind and he did not in his take pleasure in deceptions [75] such as always follow a mortal who uses devices of slanderous whisperers, a formidable enemy for both sides made for unwinnable fights, suggestions of slanders in mettle very much like foxes.

“But what useful gain is served by this?” It is relevant for I am like a floating cork, [4]staying unsoaked above the net in the salt water and holding up the deep-sea work of [80] other gear. “But it is impossible for a devious citizen to hurl an authoritative bad word against good citizens.” Nevertheless, wagging his flattering tail he tightly weaves mischief against all. I do not share that person’s confidence: may I love a friend; at an enemy, to the extent I am an enemy I will run like a wolf, [85] but at other times walk winding paths. In every political tradition a straight-tongued person comes to the front, in a monarchy, whenever an unruly demos or army is in power, and whenever a group of the wise watch over the city. It is wrong to compete against a god,—who sometimes supports the causes of those people, at other times gives others great glory, but those things [90] do not cheer the mind of the envious. Some drawing lines too long or too encompassing, plant beforehand for their heart a painful wound they will suffer before they reach what they devised in their minds, but to bear lightly a yoke after taking it upon one’s neck, helps. To kick against the goad is a slippery path. But may I delight the good, and with them keep company.

Notes to the translation

1 The exhortation he proclaims universally, calling people to respectful gratitude.

2 Referring to the song as a Castor’s song, Pindar may be suggesting, among other things, that Hieron deserves comparison with the other of the Dioscuri twins, Castor’s greater, immortal brother Polydeukes. As it turned out, the poet through his sublime voice was granted a share in the fighter’s immortality.

3 The Greek of v. 72 γένοι’ οἷος ἐσσὶ μαθών [genoi’ hoios essi mathōn] was appropriated, at least in part (μαθών —having learned and learning—is omitted in the instances I have noticed) by the 19th-century German classicist turned philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche rather early in his career as a “Motto.” When he quotes the first three words or translates “Werde der, der du bist” or “Werde der du bist” (or nonmaterially differently translated) (English, “Become who you are”) in his books, papers and surviving letters, variously annotating and giving context, he seems to advocate that people live and develop according to their conscience, true to their innermost self. One might say that he uses words of Pindar as a banner by which he anticipates 20th-century Existentialist Philosophy. (Of course, Existentialist Philosophy has other Ancient and Modern forerunners.) Nietzsche’s omission of Pindar’s μαθών fits with his immodest persona and uneven wisdom, not to mention his famously tragic adult life after his brilliant education and first years as a professor in Basel.

4 The cork on the water stays above the fray, but marks what is happening below the surface. With metaphors the poet quietly suggests a variety of ways of responding to ingrates, traitors, and slanders. That said, the positive messages of moderation, gratitude, honest straight talking, and other marks of excellence and greatness make the ode truly far-shining.

Related posts

Pindar Nemean 1, translation and notes by Jack Vaughan

Pindar Nemean 2, translation and notes by Jack Vaughan

Greek text

ΙΕΡΩΝΙ ΣΨΡΑΚΟΣΙΩι ΑΡΜΑΤΙ

μεγαλοπόλιες ὦ Συράκοσαι, βαθυπολέμου

τέμενος Ἄρεος, ἀνδρῶν ἵππων τε σιδαροχαρμᾶν δαιμόνιαι τροφοί,

ὔμμιν τόδε τᾶν λιπαρᾶν ἀπὸ Θηβᾶν φέρων

μέλος ἔρχομαι ἀγγελίαν τετραορίας ἐλελίχθονος,

5 εὐάρματος Ἱέρων ἐν ᾇ κρατέων

τηλαυγέσιν ἀνέδησεν Ὀρτυγίαν στεφάνοις,

ποταμίας ἕδος Ἀρτέμιδος, ἇς οὐκ ἄτερ

κείνας ἀγαναῖσιν ἐν χερσὶ ποικιλανίους ἐδάμασσε πώλους.

ἐπὶ γὰρ ἰοχέαιρα παρθένος χερὶ διδύμᾳ

10 ὅ τ᾽ ἐναγώνιος Ἑρμᾶς αἰγλᾶντα τίθησι κόσμον, ξεστὸν ὅταν δίφρον

ἔν θ᾽ ἅρματα πεισιχάλινα καταζευγνύῃ

σθένος ἵππιον, ὀρσοτρίαιναν εὐρυβίαν καλέων θεόν.

ἄλλοις δέ τις ἐτέλεσσεν ἄλλος ἀνὴρ

εὐαχέα βασιλεῦσιν ὕμνον, ἄποιν᾽ ἀρετᾶς.

15 κελαδέοντι μὲν ἀμφὶ Κινύραν πολλάκις

φᾶμαι Κυπρίων, τὸν ὁ χρυσοχαῖτα προφρόνως ἐφίλησ᾽ Ἀπόλλων,

ἱερέα κτίλον Ἀφροδίτας: ἄγει δὲ χάρις φίλων ποίνιμος ἀντὶ ἔργων ὀπιζομένα:

σὲ δ᾽, ὦ Δεινομένειε παῖ, Ζεφυρία πρὸ δόμων

Λοκρὶς παρθένος ἀπύει, πολεμίων καμάτων ἐξ ἀμαχάνων

20 διὰ τεὰν δύναμιν δρακεῖσ᾽ ἀσφαλές.

θεῶν δ᾽ ἐφετμαῖς Ἰξίονα φαντὶ ταῦτα βροτοῖς

λέγειν ἐν πτερόεντι τροχῷ

παντᾷ κυλινδόμενον:

τὸν εὐεργέταν ἀγαναῖς ἀμοιβαῖς ἐποιχομένους τίνεσθαι.

25 ἔμαθε δὲ σαφές. εὐμενέσσι γὰρ παρὰ Κρονίδαις

γλυκὺν ἑλὼν βίοτον, μακρὸν οὐχ ὑπέμεινεν ὄλβον, μαινομέναις φρασὶν

Ἥρας ὅτ᾽ ἐράσσατο, τὰν Διὸς εὐναὶ λάχον

πολυγαθέες: ἀλλά νιν ὕβρις εἰς ἀυάταν ὑπεράφανον

ὦρσεν: τάχα δὲ παθὼν ἐοικότ᾽ ἀνὴρ

30 ἐξαίρετον ἕλε μόχθον. αἱ δύο δ᾽ ἀμπλακίαι

φερέπονοι τελέθοντι: τὸ μὲν ἥρως ὅτι

ἐμφύλιον αἷμα πρώτιστος οὐκ ἄτερ τέχνας ἐπέμιξε θνατοῖς,

ὅτι τε μεγαλοκευθέεσσιν ἔν ποτε θαλάμοις

Διὸς ἄκοιτιν ἐπειρᾶτο. χρὴ δὲ κατ᾽ αὐτὸν αἰεὶ παντὸς ὁρᾶν μέτρον.

35 εὐναὶ δὲ παράτροποι ἐς κακότατ᾽ ἀθρόαν

ἔβαλον: ποτὶ καὶ τὸν ἵκοντ᾽: ἐπεὶ νεφέλᾳ παρελέξατο,

ψεῦδος γλυκὺ μεθέπων, ἄϊδρις ἀνήρ:

εἶδος γὰρ ὑπεροχωτάτᾳ πρέπεν οὐρανιᾶν

θυγατέρι Κρόνου: ἅντε δόλον αὐτῷ θέσαν

40 Ζηνὸς παλάμαι, καλὸν πῆμα. τὸν δὲ τετράκναμον ἔπραξε δεσμόν,

ἑὸν ὄλεθρον ὅγ᾽: ἐν δ᾽ ἀφύκτοισι γυιοπέδαις πεσὼν τὰν πολύκοινον ἀνδέξατ᾽ ἀγγελίαν.

ἄνευ οἱ Χαρίτων τέκεν γόνον ὑπερφίαλον,

μόνα καὶ μόνον, οὔτ᾽ ἐν ἀνδράσι γερασφόρον οὔτ᾽ ἐν θεῶν νόμοις:

τὸν ὀνύμαξε τράφοισα Κένταυρον, ὃς

45 ἵπποισι Μαγνητίδεσσι ἐμίγνυτ᾽ ἐν Παλίου

σφυροῖς, ἐκ δ᾽ ἐγένοντο στρατὸς

θαυμαστός, ἀμφοτέροις

ὁμοῖοι τοκεῦσι, τὰ ματρόθεν μὲν κάτω, τὰ δ᾽ ὕπερθε πατρός.

θεὸς ἅπαν ἐπὶ ἐλπίδεσσι τέκμαρ ἀνύεται,

50 θεός, ὃ καὶ πτερόεντ᾽ αἰετὸν κίχε, καὶ θαλασσαῖον παραμείβεται

δελφῖνα, καὶ ὑψιφρόνων τιν᾽ ἔκαμψε βροτῶν,

ἑτέροισι δὲ κῦδος ἀγήραον παρέδωκ᾽. ἐμὲ δὲ χρεὼν

φεύγειν δάκος ἀδινὸν κακαγοριᾶν.

εἶδον γὰρ ἑκὰς ἐὼν τὰ πόλλ᾽ ἐν ἀμαχανίᾳ

55 ψογερὸν Ἀρχίλοχον βαρυλόγοις ἔχθεσιν

πιαινόμενον: τὸ πλουτεῖν δὲ σὺν τύχᾳ πότμου σοφίας ἄριστον.

τὺ δὲ σάφα νιν ἔχεις, ἐλευθέρᾳ φρενὶ πεπαρεῖν,

πρύτανι κύριε πολλᾶν μὲν εὐστεφάνων ἀγυιᾶν καὶ στρατοῦ. εἰ δέ τις

ἤδη κτεάτεσσί τε καὶ περὶ τιμᾷ λέγει

60 ἕτερόν τιν᾽ ἀν᾽ Ἑλλάδα τῶν πάροιθε γενέσθαι ὑπέρτερον,

χαύνα πραπίδι παλαιμονεῖ κενεά.

εὐανθέα δ᾽ ἀναβάσομαι στόλον ἀμφ᾽ ἀρετᾷ

κελαδέων. νεότατι μὲν ἀρήγει θράσος

δεινῶν πολέμων: ὅθεν φαμὶ καὶ σὲ τὰν ἀπείρονα δόξαν εὑρεῖν,

65 τὰ μὲν ἐν ἱπποσόαισιν ἄνδρεσσι μαρνάμενον, τὰ δ᾽ ἐν πεζομάχαισι: βουλαὶ δὲ πρεσβύτεραι

ἀκίνδυνον ἐμοὶ ἔπος σὲ ποτὶ πάντα λόγον

ἐπαινεῖν παρέχοντι. χαῖρε. τόδε μὲν κατὰ Φοίνισσαν ἐμπολὰν

μέλος ὑπὲρ πολιᾶς ἁλὸς πέμπεται:

τὸ Καστόρειον δ᾽ ἐν Αἰολίδεσσι χορδαῖς ἑκὼν

70 ἄθρησον χάριν ἑπτακτύπου

φόρμιγγος ἀντόμενος.

γένοι᾽ οἷος ἐσσὶ μαθών: καλός τοι πίθων παρὰ παισίν, αἰεὶ

καλός. ὁ δὲ Ῥαδάμανθυς εὖ πέπραγεν, ὅτι φρενῶν

ἔλαχε καρπὸν ἀμώμητον, οὐδ᾽ ἀπάταισι θυμὸν τέρπεται ἔνδοθεν:

75 οἷα ψιθύρων παλάμαις ἕπετ᾽ αἰεὶ βροτῷ.

ἄμαχον κακὸν ἀμφοτέροις διαβολιᾶν ὑποφάτιες,

ὀργαῖς ἀτενὲς ἀλωπέκων ἴκελοι.

κερδοῖ δὲ τί μάλα τοῦτο κερδαλέον τελέθει;

ἅτε γὰρ εἰνάλιον πόνον ἐχοίσας βαθὺν

80 σκευᾶς ἑτέρας, ἀβάπτιστός εἰμι, φελλὸς ὣς ὑπὲρ ἕρκος ἅλμας.

ἀδύνατα δ᾽ ἔπος ἐκβαλεῖν κραταιὸν ἐν ἀγαθοῖς

δόλιον ἀστόν: ὅμως μὰν σαίνων ποτὶ πάντας, ἄταν πάγχυ διαπλέκει.

οὔ οἱ μετέχω θράσεος: φίλον εἴη φιλεῖν:

ποτὶ δ᾽ ἐχθρὸν ἅτ᾽ ἐχθρὸς ἐὼν λύκοιο δίκαν ὑποθεύσομαι,

85 ἄλλ᾽ ἄλλοτε πατέων ὁδοῖς σκολιαῖς.

ἐν πάντα δὲ νόμον εὐθύγλωσσος ἀνὴρ προφέρει,

παρὰ τυραννίδι, χὠπόταν ὁ λάβρος στρατός,

χὤταν πόλιν οἱ σοφοὶ τηρέωντι. χρὴ δὲ πρὸς θεὸν οὐκ ἐρίζειν,

ὃς ἀνέχει τοτὲ μὲν τὰ κείνων, τότ᾽ αὖθ᾽ ἑτέροις ἔδωκεν μέγα κῦδος. ἀλλ᾽ οὐδὲ ταῦτα νόον

90 ἰαίνει φθονερῶν: στάθμας δέ τινος ἑλκόμενοι

περισσᾶς ἐνέπαξαν ἕλκος ὀδυναρὸν ἑᾷ πρόσθε καρδίᾳ,

πρὶν ὅσα φροντίδι μητίονται τυχεῖν.

φέρειν δ᾽ ἐλαφρῶς ἐπαυχένιον λαβόντα ζυγὸν

ἀρήγει: ποτὶ κέντρον δέ τοι

95 λακτιζέμεν τελέθει

ὀλισθηρὸς οἶμος: ἁδόντα δ᾽ εἴη με τοῖς ἀγαθοῖς ὁμιλεῖν.

(Greek text copied from Perseus: Sir John Sandys, Litt.D., FBA. Pindar. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1937)

References

Works consulted, besides the Greek-English Lexicon of Liddell-Scott-Jones (Clarendon Press Oxford 1943 with New Supplement 1996) and the English-language version of Franco Montinari, Madeleine Goh, and Chad Schroeder,The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (Leiden/Boston 2015):

Cookesley, G.G. 1851. Pindarus: Carmina ad fidem textus Böckhiani, cum fragmentis et indice: notas quasdam anglice scriptas adjecit G.G. Cookesley · Volume 1 (Eton 1851) (most valuable for English-language notes on Pindar’s Olympian and Pythian Odes) (recently accessed as a GoogleBook)

The Teubner Pindar: Pindari Carmina cum Fragmentis edidit Bruno Snell. (Bibl. Scr. Graec. et Rom. Teubneriana.) Leipzig: Teubner, 1953. 2d ed. 1955.

Farnell, Lewis Richard. 1932. Critical Commentary to the Works of Pindar (London 1932, reprint Hakkert Amsterdam 1965) pp. 118-34 (makes the suggestion,followed in my translation, of enclosing dialogue-like language that seems to come from a different voice in quotation marks)

Scholia: Drachmann, A.B. 1910. Scholia Vetera in Pindari Carmina recensuit A.B. Drachmann volume II. Scholia in Pythionicas. (originally published by B.G. Teubner Verlag, Leipzig 1910, reprinted with original publisher’s permission, under license, Amsterdam [Verlag Adolf M. Hakkert] 1964)

Other: Simon Hornblower, Thucydides and Pindar: Historical Narrative and the World of Epinikian Poetry (Oxford UP 2004) (brilliant book with a copious bibliography that includes citation of a 1985 monograph by Glenn Most on Pythian 2 and Nemean 7 that was not available to me)

Friedrich Nietzsche, Kritische Studienausgabe (KSA), Sämtliche Werke in 15 Bänden, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (Berlin 1980, KSA Paperback released Munich [DTV-de Gruyter] 1999) and Friedrich Nietzsche, Sämtliche Briefe in 8 Bänden, ed. Giorgio Colli and Mazzino Montinari (1975-84, KSA Paperback Munich [DTV-de Gruyter] 1986, 2d ed. 2003) (the indices of both multivolume editions give volume and page numbers for references and allusions to Pindar generally and to specific poems of which the noted line in Pythian 2 is most often quoted and alluded to)

Image credits

Relief with the punishment of Ixion (2nd century) in the Side Archaeological Museum

Photo: © Ad Meskens, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license via Wikimedia Commons

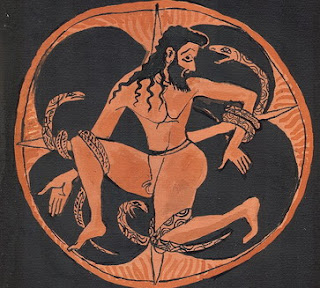

Ixion, Item in Geneva Museum of Arts.

No details provided on Wikimedia Commons.

Perhaps Beazley 8713: “Red-figure, Cup C shape, 500–540 BCE”

Photo: Gakoz. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

__

Jack Vaughan is a Texas attorney; he was educated in the US and Europe, and has been an active member of the Kosmos Society since the conclusion of HeroesX v2 (January 2014).