Last time we looked at food and drink for health and well-being. This time we look at less salubrious examples of eating and drinking, many of which have disastrous consequences.

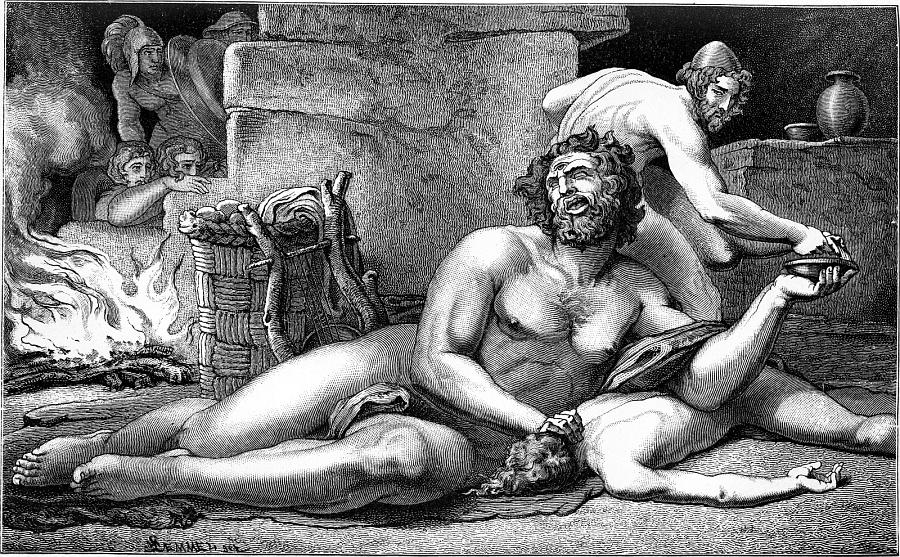

Kronos, having usurped his own father, did not want the same thing to happen to him.

Rhea too, embraced by Kronos, bore renowned children, Hestia, Demeter, and Hera of-the-golden-sandals, 455 and mighty Hādēs, who inhabits halls beneath the earth, having a ruthless heart; and loud-resounding Poseidon, and counseling Zeus, father of gods as well as men, by whose thunder also the broad earth quakes. And them indeed did huge Kronos devour [katapinein], 460 namely, every one who came to the mother’s knees from her holy womb [nēdus], with this intent, that none other of the illustrious sky-born might hold royal honor among the immortals.

Hesiod Theogony 453–462, adapted from Sourcebook[1]

But Rhea manages to hide the birth of Zeus, and fools Kronos:

485 But to the great prince, the son of Sky, former sovereign of the gods, she gave a huge stone, having wrapped it in swaddling clothes: which he then took in his hands, and stowed away into his belly [nēdus], wretch as he was, nor did he consider in his mind that against him for the future his own invincible and untroubled son was left instead of a stone, 490 who was shortly about to subdue him by strength of hand, and to drive him from his honors, and himself to reign among the immortals. Quickly then throve the spirit and beauteous limbs of the king, and, as years came round, having been beguiled by the wise counsels of Earth 495 huge Kronos, wily counselor, let loose again his offspring, having been conquered by the arts and strength of his son. And first he disgorged [exemeîn] the stone, since he swallowed [katapinein] it last.

Hesiod Theogony 485–497, adapted from Sourcebook

The myth which sets the pattern for messed-up eating for mortals was the one organized for gods and humans at a time when they were eating together. It was Prometheus who disrupted this pattern.

535 When the gods and mortal men were contending at Mekone, then did he [Prometheus] set before him [Zeus] a huge ox [boûs], having divided it with ready mind, studying to deceive the wisdom [noos] of Zeus. For here, on the one hand, he deposited the flesh [sarx] and entrails [enkata] with rich [piōn] fat [dēmós] on the hide, having covered it with the belly [gastēr] of the ox [boeios]; and there, on the other hand, he laid down, 540 having well disposed them with subtle craft, the white bones [osteon] of the ox [boûs], covering them with white fat [dēmós]. Then it was that the father of gods and men addressed him, “Son of Iapetos, far-famed among all kings, how unfairly, good friend, you have divided the portions [moîra].” 545 Thus spoke rebukingly Zeus, skilled in imperishable counsels. And him in his turn wily Prometheus addressed, laughing low, but he was not forgetful of subtle craft: “Most glorious Zeus, greatest of ever-living gods, choose which of these your inclination within your breast bids you.” He spoke in subtlety: 550 but Zeus knowing imperishable counsels was aware, in fact, and not ignorant of his guile; and was boding in his heart evils to mortal men, which also were about to find accomplishment. Then with both hands he lifted up the white fat [aleiphar]. But he was incensed in mind, and wrath came around him in spirit, 555 when he saw the white bones [osteon] of the ox [boûs] arranged with guileful art. And thenceforth the tribes of men on the earth burn to the immortals white bones [osteon] on fragrant [thuēeis] altars. Then cloud-compelling Zeus addressed him, greatly displeased: “Son of Iapetos, skilled in wise plans beyond all, 560 you do not, good sir, yet forget subtle craft.” Thus spoke in his wrath Zeus knowing imperishable counsels: from that time forward, ever mindful of the fraud, he did not give the strength of untiring fire to wretched mortal men, who dwell upon the earth. 565 But the good son of Iapetos cheated him, and stole the far-seen splendor of untiring fire in a hollow fennel-stalk; but it stung High-thundering Zeus to his heart’s core, and incensed his spirit, when he saw the radiance of fire conspicuous among men.

Hesiod Theogony 535–570, adapted from Sourcebook

Jan-Mathieu Carbon analyzes this example as follows:

Such myths have also been taken as a vision of paradise lost: they are principally seen to outline the hierarchical distinctions between divine beings and mortals. Though they had formerly feasted together, gods now only received the sublimated fatty smoke (κνῖσα, created by the action of θύω, θυσία) from essentially inedible portions of fat and bone, while humans ate meat; gods were immortal and ate separately and differently, while humans, except perhaps for a few blessed heroes, could not dine at their table. Only in a limited number of myths or rituals is it admitted that “the divide” between gods and humans could be “bridged” or “negotiated” by specific or more substantial offerings.[2]

In part 1, we looked at some examples of correctly conducted sacrifices where the offerings were made to the gods.

But if this practice is not carried out properly there are dire consequences. One disturbing example occurs in the Odyssey, when Odysseus’ men are stuck on Thrinacia, and decide to eat some of the cattle on the island—despite having been warned not to because they belong to the Sun god, Helios.

As long as wheat [sîtos] and wine [oinos] held out the men did not touch the cattle [boûs] when they were hungry; when, however, they had eaten all there was in the ship, [330] they were forced to go further afield, with hook and line, catching fish [ikhthus] and birds [ornis], and taking whatever they could lay their hands on; for hunger [limos] distressed their bellies [gastēr]. … Meanwhile Eurylokhos had been giving evil counsel to the men, [340] ‘Listen to me,’ said he, ‘my poor comrades. All deaths are bad enough but there is none so bad as famine [limos]. Why should not we drive in the best of these cows [boûs] and offer them in sacrifice to the immortal gods? [345] If we ever get back to Ithaca, we can build a fine temple to the sun-god and enrich it with every kind of ornament; if, however, he is determined to sink our ship out of revenge for these horned cattle [boûs], and the other gods are of the same mind, [350] I for one would rather drink [khaskein] the waves once for all and have done with it, than be starved to death by inches [streugesthai] in such a desert island as this is.’

Thus spoke Eurylokhos, and the men approved his words. Now the cattle [boûs], so fair and goodly, [355] were feeding not far from the ship; the men, therefore drove in the best of the cattle [boûs], and they all stood round them saying their prayers, and using young oak-shoots, for there was no white barley [krî] left on the ship. When they had done praying they killed [sphazein] the cows and dressed [derein] their carcasses; [360] they cut out the thigh bones [mēros], wrapped them round in two layers of fat [knîsa], and set some pieces of raw meat [hōmotheteîn] on top of them. They had no wine [methu] with which to make drink-offerings [leibein] over the sacrifice while it was cooking, so they kept pouring on [spendein] a little water [hudōr] from time to time while the innards [enkata] were being grilled [epotân]; then, when the thigh bones [mēros] were burned [kaiein] and they had tasted [patesthai] the innards [splankhnon], [365] they cut the rest up small and put the pieces upon the spits [obelos]. …

As soon as I got down to my ship and to the sea shore I rebuked each one of the men separately, but we could see no way out of it, for the cows [boûs] were dead already. And indeed the gods began at once to show signs and wonders among us, [395] for the hides [rhinos] of the cattle crawled about, and the joints [kreas] upon the spits began to low like cows, and the meat, whether cooked [optaleos] or raw [ōmos], kept on making a noise just as cows do.

Odyssey 12.328–332, 339–365, 391–396, adapted from Sourcebook[3]

As a result of their actions and Helios’ anger, Zeus promises to “shiver their ship into little pieces with a bolt of white lightning as soon as they get out to sea.” (12.388), and indeed all the men die, except for Odysseus, who had not taken part in this activity.

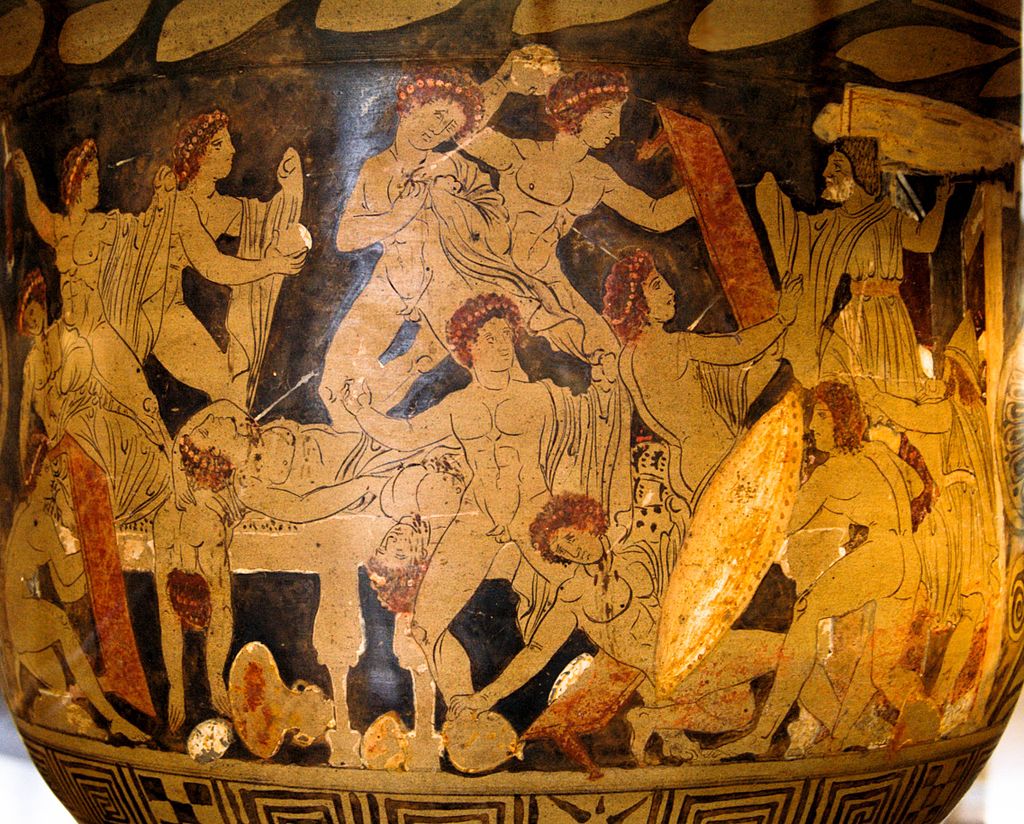

There are other disastrous meals in the Odyssey: when some of the men eat the Lotus they forget about going home (Odyssey 9.91–102), and when Odysseus takes some of his men to investigate the cave of the Cyclops Polyphemus, they make free with his provisions, and this breach of xeniā results in Polyphemus himself eating some of the men!

We lit a fire, offered some of the cheeses [turos] in sacrifice, ate [esthein] others of them, and then sat waiting till the Cyclops should come in with his sheep. …

The cruel wretch granted me not one word of answer, but with a sudden clutch he gripped up two of my men at once and dashed them down upon the ground as though they had been puppies. [290] Their brains [enkephalos] were shed upon the ground, and the earth was wet with their blood. Then he tore them limb from limb and prepared his meal [dorpon]. He gobbled [esthein] them up like a lion in the wilderness, entrails [enkata], flesh [sarx], and bones [osteon] full of marrow [mueloeis], without leaving anything.

Odyssey 9.231–233, 287–293), adapted from Sourcebook

As part of his plan to effect their escape, Odysseus offers Polyphemus some exquisite, but very strong, wine which he drinks unmixed: another aberration since wine was usually mixed with water.

…he reeled, and fell sprawling face upwards on the ground. His great neck hung heavily backwards and a deep sleep took hold upon him. Presently he threw up from his throat [pharunx] both wine [oinos] and the gobbets [psōmos] of human flesh on which he had been gorging, and vomited [ereugesthai] for he was very drunk [oinobareiōn].

Odyssey 9.371–374, adapted from Sourcebook

The fact that Kronos ate his children may be because he was a Titan, one of the original deities, unlike those Olympian gods who—eventually—only consumed ambrosia and nectar. And that Polyphemus ate humans is perhaps understandable since he is a giant, a type of monster. But for humans to eat human flesh is completely taboo. However, there are myths in which this does occur.

One example is the shocking behavior of Tydeus during the war against Thebes:

Melanippus, the remaining one of the sons of Astacus, wounded Tydeus in the belly [gastēr]. As he lay half dead, Athena brought a medicine [pharmakon] which she had begged of Zeus, and by which she intended to make him immortal. But Amphiaraus hated Tydeus for thwarting him by persuading the Argives to march to Thebes; so when he perceived the intention of the goddess he cut off the head of Melanippus and gave it to Tydeus, who, wounded though he was, had killed him. And Tydeus split open the head and gulped up [ekropheîn] the brains [enkephalon]. But when Athena saw that, in disgust she grudged and withheld the intended benefit.

Apollodorus Library 3.6.8, adapted from translation by Sir James George Frazer[4]

Another example is where the meal was taken unwittingly. The two sons of Pelops, Thyestes and Atreus, who were already in contention over who should rule Mycenae, when Atreus discovered that his wife Aerope had been in an adulterous relationship with his brother.

…he sent a herald to Thyestes with a proposal of accommodation; and when he had lured Thyestes by a pretence of friendship, he slaughtered the sons, Aglaus, Callileon, and Orchomenus, whom Thyestes had by a Naiad nymph, though they had sat down as suppliants on the altar of Zeus. And having cut them limb from limb and boiled [kathepsein] them, he served them up to Thyestes without the extremities; and when Thyestes had eaten heartily of them, he showed him the extremities, and cast him out of the country.

Apollodorus Epitome E.2.13, adapted from translation by Sir James George Frazer.[5]

In a later generation, Atreus’ son Agamemnon encounters Thyestes’ son Aegisthus at a feast, and although no humans are consumed, there is a disastrous outcome for Agamemnon, as his shade tells Odysseus in Hades:

Aegisthus [410] and my wicked wife were the death of me between them. He asked me to his house, feasted [deipnizein] me, and then butchered [katakteinein] me most miserably as though I were an ox [boûs] at the manger [phatnē], while all around me my comrades were slain like pigs [sûs] [415] for the wedding breakfast [gamos], or dinner-party [eranos], or gourmet feast [eilapinē] of some great nobleman. You must have seen numbers of men killed either in a general engagement, or in single combat, but you never saw anything so truly pitiable as the way in which we fell in that hall, with the mixing-bowl [kratēr] and the loaded [420] tables [trapeza] lying all about, and the ground reeking with our blood. I heard Priam’s daughter Kassandra scream as treacherous Clytemnestra killed her close beside me.

Odyssey 11.409–423, adapted from Sourcebook

Another scene of slaughter after a meal occurs later in the Odyssey: this time it is Odysseus who initiates the killing of the suitors:

Then he aimed a deadly arrow at Antinoos, who was about to take up a two-handled [10] gold cup to drink [pinein] his wine [oinos] and already had it in his hands. … [15] The arrow struck Antinoos in the throat, and the point went clean through his neck, so that he fell over and the cup dropped from his hand, while a thick stream of blood gushed from his nostrils. He kicked [20] the table [trapeza] from him and upset the food [eîdar] on it, so that the bread [sîtos] and roasted [optân] meats [kreas] were all soiled as they fell over on to the ground.

Odyssey 22.8–11, 15–21, adapted from Sourcebook

In part 2 we shared a passage where Hekamede prepared a restorative concoction. Circe prepares a similar version for Odysseus’ men—but with a twist:

When she had got them into her house, she set them upon benches and seats and mixed them a drink with cheese [turos], meal [alphiton], honey [meli], [235] and Pramnian wine [oinos] but she drugged the food [sîtos] with wicked poisons [pharmakon] to make them forget their homes, and when they had drunk [ekpinein] she turned them into pigs by a stroke of her wand, and shut them up in her pigsties.

Odyssey 10.233–238, adapted from Sourcebook

Fortunately, with Hermes’ help, when Odysseus arrives he is able to resist the potion, overcome Circe, and have her restore his men to their original forms. Her drug had an effect on the men, but it was not a deadly poison. However, more toxic drugs could be used. Pausanias gives an account of Philip, son of Demetrios, who used poison ruthlessly:

{7.7.5} When Philip, the son of Demetrios, reached man’s estate, and Antigonos without reluctance handed over the sovereignty of the Macedonians, he struck fear into the hearts of all the Greeks. He copied Philip, the son of Amyntas, who was not his ancestor but really his master, especially by flattering those who were willing to betray their country for their private advantage. At banquets [sumposion] he would give the right hand of friendship offering [propinein] cups [kulix] filled not with wine [oinos] but with deadly poison [pharmakon], a thing which I believe never entered the head of Philip the son of Amyntas, but poisoning [pharmakon] sat very lightly on the conscience of Philip the son of Demetrios.

Pausanias Description of Greece 7.7.5[6]

Not all poisonous substances are administered deliberately, and it pays to be careful when foraging for food:

According to Eparchides, the poet Euripides was once staying in the isle of Icaros, when a certain woman and her children, two grown-up sons and one unmarried daughter, all died of poisonous [thanasimos] mushrooms [mukēs] which they ate [esthiein] in the fields, whereupon he composed the following inscription:

O Sun whose path lies through the unaging vault of heaven, did thy eye ever behold so sad a thing as a mother and a maiden daughter and two sons perishing on the same destined day?

CURFRAG.tlg-0006.2

Athenaeus Doctors at Dinner [on mushrooms] in Elegy and Iambus 1.26.2, adapted from translation by J.M. Edmonds[7]

Pausanias refers to another poisonous plant that can easily be mistaken for a harmless one, which grows on Sardinia:

Except for one plant [botanē], the island is free from poisons [pharmakon]. This deadly herb [poa] is like celery [selinon], and they say that those who eat [esthiein] it die laughing. That is why Homer, and men after him, call unwholesome [not hugiēs] laughter sardonic. The herb [poa] grows mostly around springs, but does not impart any of its poison [ios] to the water [hudōr].

Pausanias 10.17.13, adapted from Pausanias Reader[8]

But there can be ill effects even from normal food. Hippocrates warns of the consequences of taking meals at unaccustomed times:

That the discomforts a man feels after unseasonable [akairos] abstinence [kenōsis] are no less than those of unseasonable repletion [plērōsis], it were well to learn by a reference to men in health [hugiainein]. For some of them benefit by taking one meal only each day [monositeîn], and because of this benefit they make a rule of arranging it so; others again, because of the same reason, that they are benefited thereby, take lunch [aristân] also. …. Some, who lunch [aristân] although it does not suit them, forthwith become heavy [barus] and sluggish [nōthros] in body and in mind, a prey to yawning, drowsiness and thirst [dipsa]; while, if they go on to eat dinner [epideipneîn] as well, flatulence [phûsa] follows with colic [strophos] and violent diarrhœa [from koilia]. Many have found such action to result in a serious illness [nosos], even if the quantity of food [sition] they take twice a day be no greater than that which they have grown accustomed to digest once a day. On the other hand, if a man who has grown accustomed, and has found it beneficial, to take lunch [aristân], should miss taking it, he suffers, as soon as the lunch-hour is passed, from prostrating weakness [adunamiā], trembling [tromos] and faintness [a-psukhiā]. … Besides all this, when he attempts to dine [deipnein], he has the following troubles: his food is less pleasant [a-ēdēs], and he cannot digest what formerly he used to dine [deipneîn] on when he had lunch [aristân]. The mere food, descending into the bowels [koilia] with colic [strophos] and noise, burns them, and disturbed sleep follows, accompanied by wild and troubled dreams.

Hippocrates Ancient Medicine 10, adapted from translation by W.H.S. Jones[9]

We have shared just a few passages, mythological and otherwise, accidental and deliberate, in which people suffer disastrous consequences as a result of inappropriate eating and drinking. We invite you to share in the Forum any other examples you come across.

Selected vocabulary

Based on definitions in LSJ[10]:

adunamiā want of strength, debility

aēdēs adj. distasteful, nauseous, unpleasant

akairos ill-tied, unseasonable

aleiphar oil, fat

alphiton barley

apsukhiā swooning, syncope, faint-heartedness

aristân to take a midday meal

barus adj. heavy

boeios adj. of an ox

botanē pasture, fodder, herb

boûs bullock, bull, ox, or cow

deipneîn to make a meal, dine

deipnizein to entertain at dinner

dēmós fat (not to be confused with dêmos, district)

derein to skin, flay

dipsa thirst

dorpon evening meal

eîdar food

eilapinē solemn feast or banquet

ekpinein to drink out or off, quaff

ekropheîn to drink out, gulp down, swill

enkata innards, entrails

enkephalos brain

epideipneîn to east a second meal

epotân to roast besides or after

eranos meal to which each contributed his share, picnic

ereugesthai to belch out, disgorge

esthein, esthiein to eat

exemeîn to vomit forth, disgorge

gamos wedding

gastēr paunch, belly

hōmotheteîn to place the raw pieces

hudōr water

hugiainein to be sound, healthy, or in health

hugiēs adj. healthy, sound

ikhthus fish

ios poison, venom

kaiein to kindle, burn

katakteinein to kill, slay

katapinein to gulp, swallow down, swallow, consume

kathepsein to boil down

kenōsis an emptying, depletion

khaskein to yawn, gape, to swallow

knîsa I steam and odour of fat which exhales from roasting meat, smell or savour of a burnt sacrifice; II that which causes this smell, fat caul

koilia abdomen, stomach, intestines, bowels

kratēr mixing-bowl

kreas meat, flesh

krî barley

kulix cup, wine-cup

leibein to pour, pour forth, make a libation

limos hunger, famine

meli honey

mēros thigh

methu wine

moîra part, portion

monositeîn to eat but one meal in the day

mukēs mushroom

mueloeis adj. full of marrow

nēdus belly, stomach; womb

nōthros adj. sluggish, slothful, torpid

nosos sickness, disease, plague

obelos spit

oinobareiōn heavy or drunk with wine

oinos wine

ōmos adj. raw, uncooked

optaleos adj. roasted, broiled

optân to roast, broil

ornis bird

osteon bone

patesthai to eat, taste

pharmakon drug

pharunx throat

phatnē manger, crib

phûsa wind, flatus, breaking of wind

pinein to drink

piōn fat

plērōsis a filling up, filling; sensual gratification

poa grass, herb, plant

propinein to drink first, to drink up; to drink a pledge; make a drinking-present

psōmos morsel, bit, gobbet

rhinos skin, hide

sarx flesh

selinon celery

sition grain, corn; bread,; victuals, provisions

sîtos grain; bread; food

spendein to make a drink-offering, to pour

sphazein to slay, slaughter

splankhnon innards

streugesthai to be squeezed out in drops: metaph. to be drained of one’s strength, exhausted

strophos twisting of the bowels, colic

sumposion drinking-party, symposium

sûs pig

thanasimos adj. deadly, fatal

thuēeis adj. smoking or smelling with incense, fragrant

trapeza table, dining-table

tromos a trembling, quaking, quivering

turos cheese

See also

Food and drink | Part 1: Homer and Hesiod

Food and drink | Part 2: Health and nutrition

Notes

1 Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook: Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English. Gregory Nagy. 2013.

https://chs.harvard.edu/book/the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours-sourcebook

Hesiodic Theogony: 1–115 Translated by Gregory Nagy, 116–1022 Translated by J. Banks and adapted by Gregory Nagy.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Theogony. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

2 Carbon, Jan-Mathieu (Mat). “At the Table of the Gods? Divine Appetites and Animal Sacrifice.” CHS Research Bulletin 5, no. 2 (2017).

https://research-bulletin.chs.harvard.edu/2017/09/11/divine-appetites-animal-sacrifice/

3 Homeric Odyssey: Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919.

Online at Perseus

4 Apollodorus. English and Greek texts: Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer’s notes.

Online at Perseus

5 The Epitome is in the same edition as The Library, as above.

Online at Perseus

6 Description of Greece: A Pausanias Reader. Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy

Online at https://chs.harvard.edu/description-of-greece-a-pausanias-reader/

Greek text: Pausanias. Pausaniae Graeciae Descriptio, 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903.

Online at Perseus

7 English and Greek texts: Elegy and Iambus. with an English Translation by. J. M. Edmonds. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. 1.

Online at Perseus

8 Description of Greece: A Pausanias Reader. Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy.

Online at https://chs.harvard.edu/description-of-greece-a-pausanias-reader/

Greek text: Pausanias. Pausaniae Graeciae Descriptio, 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903.

Online at Perseus

9 English and Greek texts: Hippocrates Collected Works I. Hippocrates. W. H. S. Jones. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1868.

Online at Perseus

10 LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones, with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus

Texts accessed March 2022

Image credits

Peter Paul Rubens: Saturn, Jupiter’s father, devours one of his sons. 1636–1638.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Heinrich Füger: Prometheus Brings Fire to Mankind. 1790 or 1817.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Pellegrino Tibaldi: The companions of Odysseus rob the cattle of Helios. 1554–1556

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Illustration: Odysseus and Polyphemus. From Schwab, Gustav: “Sagen des Klassischen Altertums” (1882).

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Tydeus eating Melanippus’ brains. Detail from Etruscan terracotta high relief on the central columen plaque of Temple A, Pyrgi, the port of Caere. c 470-460 BCE

Photo: Dan Diffendale, Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0), via Flickr

Atreus making Thyestes eat his three sons. Miniature from ‘Des cas des nobles hommes et femmes’ c 1410.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ixion Painter: Mnêstêrophonía: slaughter of the suitors, Side A from a Campanian (Capouan?) red-figure bell-krater, ca. 330 BCE. Louvre.

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Christoffel Pierson: Circe and Odysseus’ Company, c 1610. Slovenská národná galéria, SNG

Public domain, via webumenia.sk

Franciszek Kostrzewski: Mushroom picking, c 1860

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Attributed to Dokimasia P by Beazley: Interior of Athenian red-figure cup, c 500–450 BCE (Beazley)

Photo: Sailko, Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images accessed February/March 2022

___

Hélène Emeriaud, Janet Ozsolak, and Sarah Scott are members of Kosmos Society