Listening to or reading a Greek tragedy is not an easy exercise. When the chorus appears, often people pass the text, if they are reading, and start daydreaming if they are part of an audience. It was like that for me for a long period, then I discovered the beauty of the text. I began to find interest in the place given to the chorus in a drama.

We know little about the chorus. We have only a few written texts describing it, and even less iconography showing a chorus in action in a tragedy.

Claude Calame gives us some useful information on the number of participants.[1] He indicates that the chorus regrouped in a rectangle, which surprised me. I had always thought that the circular form was the arrangement favored by tragedy, like in lyric chorus.

As for the number of participants, Calame writes:

In tragedy and comedy, choruses were made up of a fixed number of participants, men and women. The note in the Suda, mentioned above in connection with the definition of the term χορός, gives fifteen members for the tragic chorus and twenty-four for the comic, a number that corresponds both to information from other sources and to what can be gleaned from the plays themselves. Philological opinion agrees with the number twelve for the choruses of Aeschylus, fifteen for those of Sophocles and Euripides.[2]

So what does the chorus do in a tragic play? It performs vocally in a group.

According to Aristotle it should be considered as one of the actors.

The chorus too must be regarded as one of the actors. It must be part of the whole and share in the action, not as in Euripides but as in Sophocles.

(Aristotle Poetics 1456a, translated by W.H. Fyfe)[3]

The chorus describes, comments, sings, dances, intervenes, recites, reacts, represents the past, and builds links with the audience.

At Kosmos Society, khoros [χορός], chorus, is one of the Core Vocab words studied by Sarah Scott[4]: ”a Core Vocab word is khoros [χορός] which Professor Nagy defines as “‘chorus’ = ‘group of singers/dancers’. This is clear when we come to drama: in the tragedies the role of the Chorus is defined in The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours,” and she quotes this passage:

The chorus represents a “go-between” or “twilight zone” between the heroes of the there-and-then and the audience of the here-and-now, which happens to be, in the case of the dramas, Athens in the 5th century. The chorus reacts both as if it were the audience itself and as if they were contemporaries of the heroes. The members of the chorus, who sang and danced the roles of groups such as old men or young girls who are “on the scene” in the mythical world of heroes, were non-professionals, whereas the actors (the first, second, and third actor), who spoke the parts of the main characters, were professionals. For Athenian society, the ritual emphasis is on the experience of the pre-adult chorus and, through them, of the adult audience

H24H ‘Introduction to tragedy’, III§4[5]

Jack Vaughan in a very precise article[6] gives the place of entrance and of exit for the chorus:

“The Parodos (the Chorus’ “way on/way to”) is the name of this first song (or song sequence) of the Chorus which is delivered presumably sung or chanted as the Chorus makes its entrance into the “orchestra” (the pit in front of the proscenium, or stage from which the individual actors hold forth).

Exodos (“way out”—the Greek word from which we get the modern word “exodus”) is the matching term for exit of the chorus, all that is said, sung, or done by the Chorus and the characters left on stage after the Chorus’ last stasimon.”

Vaughan also evokes that in some cases of “late Euripidean lyrics voiced before a silent Chorus, one may hear a “sound of silence” from the Chorus.”

When did I change my mind and stopped skipping the chorus part? When I finally realized the power of the words as I read the “Ode to Man” in Sophocles’ Antigone:

Chorus

strophe 1

Wonders / terrors [deina, pl.] are many, and none is more wonderful / terrible [deinon] than man. |335 This spans the sea [pontos], even when it surges white before the gales of the south wind, and makes a path under swells that threaten to engulf him. Earth [Gaiā], too, the eldest of the gods, the unwilting [aphthitos], the unwearied [a-kamatos], |340 he wears away to his own ends, turning the soil with the offspring [genos] of horses as the plows weave to and fro year after year.antistrophe 1

The feather-brained [lacking noos] tribe of birds |345 and the clans of wild beasts and the sea-brood of the sea [pontos] he snares in the meshes of his twisted nets, and he leads them captive, very-skilled man. He masters by his arts |350 the beast who dwells in the wilds and roams the hills. He tames the shaggy-maned horse, putting the yoke upon its neck, and tames the tireless mountain bull.strophe 2

Speech and thought [phronēma, from phrēn] fast as the wind |355 and the moods that give order to a city he has taught himself, and how to flee the arrows of the inhospitable frost under clear skies and the arrows of the storming rain. |360 He has resource for everything. Lacking resource in nothing he strides towards what must come. From Hādēs alone he shall procure no escape, but from hopeless diseases he has devised flights.antistrophe 2

|365 Possessing resourceful skill [sophon], a subtlety beyond expectation, he moves now to evil [kakon], now to good [esthlon]. When he honors the laws [nomoi] of the land and the justice [dikē] of the gods to which he is bound by oath, |370 he stands high in his polis. But banned from his polis is he who, thanks to [kharis] his rashness, couples with disgrace. Never may he share my home, |375 never think my thoughts [phrēn, vb.part], who does these things!Sophocles Antigone 334–375, Sourcebook[7]

The poetical words transport us into an imaginary world, but at the same time they evoke real deeds and arts. They make us dream of what is, or what could be, of all the possibilities surrounding us, and also the frailty of humankind. People die, indeed. The text is ambiguous from the start with the choice of wonderful / terrible [deinon].

It could as well concern Creon or Antigone or her brothers or the citizens of Thebes, or the audience or the entire humanity. The Ode is blessed with a universal resonance.

The other passage which played also a key role in my change of opinion concerning the chorus was in Euripides’ Electra. It shows the potential use of dancing by the chorus. The chorus is inviting Electra to dance with them, and everyone may feel the urge to dance, even if it is rather a danse macabre, after Aegisthus’murder.

Χορός

θὲς ἐς χορόν, ὦ φίλα, ἴχνος,

860 ὡς νεβρὸς οὐράνιον

πήδημα κουφίζουσα σὺν ἀγλαΐᾳ.

νικᾷ στεφαναφορίαν

† κρείσσω τοῖς † παρ᾽ Ἀλφειοῦ ῥεέθροισι τελέσσας

κασίγνητος σέθεν: ἀλλ᾽ ἐπάειδε

865 καλλίνικον ᾠδὰν ἐμῷ χορῷ.Chorus

Set your step to the dance, my dear, [860] like a fawn leaping high up to heaven with joy. Your brother is victorious and has accomplished the wearing of a crown . . . beside the streams of Alpheus. Come sing [865] a glorious victory ode, to my dance.

Euripides Electra 859–865[8]

However, we have to be careful with our interpretation of the way a chorus would dance in a tragedy at that time.

As Armand D’Angour writes:

The indications of dance are scant, but suggest that the motions of the chorus itself will have been slow and solemn, with upper-body movements and hand gestures playing a more important role than those of feet or legs, which in any case would have been swathed in the sombre long robes of city elders.

Armand D’Angour, The Music of Sophocles’ Ode to Man[9]

Join the conversation at the forums to share your thoughts and favorite chorus passage.

Notes

[1] Calame, Claude. 2001. Choruses of Young Women in Ancient Greece: Their Morphology, Religious Roles, and Social Functions.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Calame.Choruses_of_Young_Women_in_Ancient_Greece.2001

[2] Calame 2001, Chapter 2: “Morphology of the Lyric Chorus,” 2.1.1

[3] Aristotle Poetics 1456a. Aristotle. Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vol. 23, translated by W.H. Fyfe. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1932. Online at Perseus

[5] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[6] The Structure of Greek Tragedy: An Overview, by Jack Vaughan.

[7] Sophocles Antigone Translated by Richard Jebb, revised by Pierre Habel, further revised by Gregory Nagy. Newly revised by members of Kosmos Society (then Hour 25). Published under a Creative Commons License 3.0.

[8] Greek text: Euripides. Euripidis Fabulae, vol 2. Gilbert Murray. Oxford. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1913.

Online at Perseus

English text: Euripides. The Complete Greek Drama, edited by Whitney J. Oates and Eugene O’Neill, Jr. in two volumes. 2. Electra, translated by E. P. Coleridge. New York. Random House. 1938.

Online at Perseus

[9] Armand D’Angour, “The Music of Sophocles’ Ode to Man,” in Antigone

Online publication: antigonejournal.com

Image credits

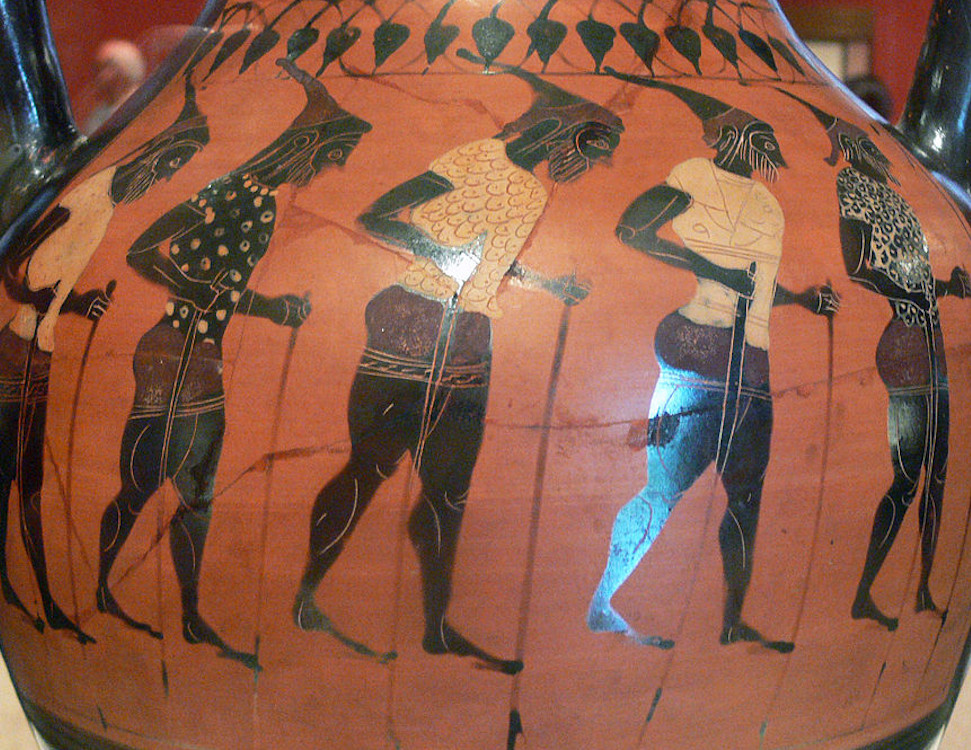

Storage jar with a chorus of stilt walkers, 550–525 BCE, Athens. Getty Villa.

Photo: Remi Mathis. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Stills from student performances of the “Ode to Man” from Antigone.

Videos available via Kosmos Society.

___

Hélène Emeriaud is a Team member at HeroesX, a MOOC on edX. She studied ancient Greek at school in France and for several years at the University of Minnesota. She holds a degree in Education from Montreal University, and a Master of Education from McGill University. She is an active participant and member of the Editorial Team in the Kosmos Society with a particular interest in ancient Greek and Latin language learning.