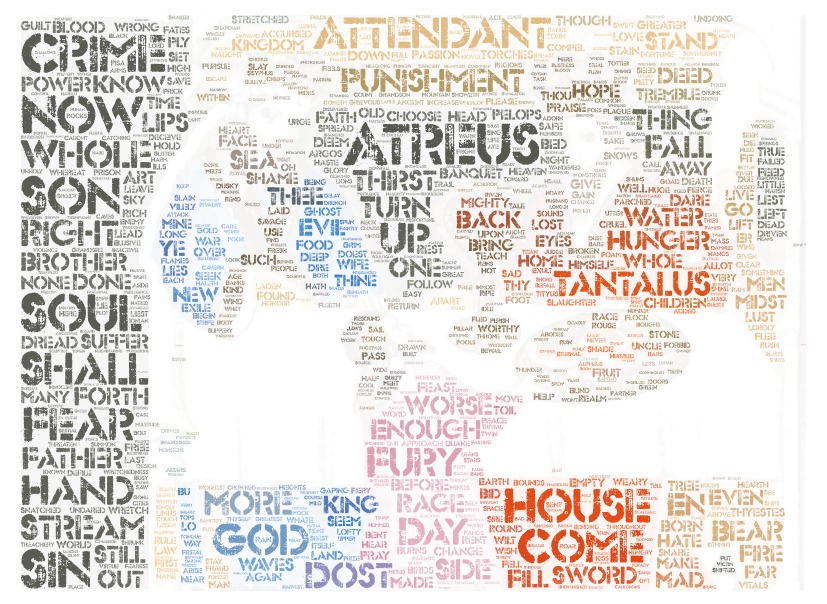

Atreus

… I must dare some crime, atrocious, bloody, such as my brother would more wish were his. Crimes thou dost not avenge, save as thou dost surpass them. And what crime can be so dire as to overtop his sin? Does he lie downcast? Does he in prosperity endure control, rest in defeat? I know the untamable spirit of the man; bent it cannot be – but it can be broken.

from the translation by Frank Justus Miller.

To start the new year we will be reading Seneca’s tragedy Thyestes.

Lucius Annaeus Seneca, or Seneca the Younger, (c 4 BCE–65 CE) was, according to Encyclopedia Britannica[1], not only a writer of tragedy, but also a “Roman philosopher, statesman [and] orator”. Born in Spain, he went to Rome as a boy where he received his education, and after a spell in Egypt for his health, he returned to Rome where he was active in law and politics. However, the emperor Claudius banished him to Corsica where he studied philosophy. He later returned to Rome and was favored by Nero. Britannica continues, “Seneca and Burrus, although provincials from Spain and Gaul, understood the problems of the Roman world. They introduced fiscal and judicial reforms and fostered a more humane attitude toward slaves.” However, after the murder of Agrippina Seneca returned to philosophy, and, implicated in a plot to kill Nero, was finally forced to commit suicide.

Since our Book Club selection is a play, in addition to our usual Forum and Zoom discussion, we will also have a read-through. We have found previously that this activity helps our understanding of plays in terms of performance. In the case of Seneca’s plays, Britannica says that they are “[i]ntended for play readings rather than public presentation, the pitch is a high monotone, emphasizing the lurid and the supernatural.”

As with many Roman authors, Seneca drew on Greek mythology; there was a Thyestes by Euripides, now lost, so Seneca may have been familiar with that version. The action deals with the rivalry between Atreus (father of Agamemnon and Menelaos), and his brother Thyestes. They are part of a cursed family: Murgatroyd’s introductory notes[2] provide a context for this play with the mythological background of Tantalos and Pelops, and the next generations, Agamemnon, Aegisthus, and Orestes.

Here are links to some free online translations:

- Paul Murgatroyd, at Poetry in Translation, to read online or download

- Frank Justus Miller, 1917, at theoi.com to read online

or at archive.org to read online or download - Watson Bradshaw, 1902, at archive.org to read online or download

The Latin text is available at Perseus.

Discussion starts and continues in the Forum.

The play read-through will be via Zoom on on Tuesday January 17 at 11 a.m. EST, and the Zoom discussion will be on Tuesday January 31, also at 11 a.m. EST. Links will be posted in the Forum on the days in question.

See also

Reading Greek Tragedy Online: A reading and discussion of Seneca’s Thyestes, hosted by Joel Christensen (Brandeis University) with special guest Helen Slaney (La Trobe University). The cast includes Tim Delap, Evelyn Miller, Paul O’Mahony, David Rubin, Sara Valentine.

on the Center for Hellenic Studies YouTube channel. There is also a list of suggestions for further reading.

Notes

1 Article “Seneca” by Donald Reynolds Dudley, at Encyclopedia Britannica

2 Seneca Thyestes translated by Paul Murgatroyd, at Poetry in Translation