Figure 1: Hēraklēs sails across the sea in the cup-boat of the sun-god Helios. The hero wears a lion-skin cape and holds a club and bow in his hands.[1]

During his numerous and formidable adventures Hēraklēs had to face the sea and to brave storms. In this post we are exploring some of Hēraklēs’ maritime journeys. He assembled large fleets for distant expeditions. While on one of his labors he also set up the Pillars of Hēraklēs, very far away from Greece. And he traveled in the golden cup-boat of Helios.

Gregory Nagy in an article[2] for Classical Inquiries writes about the fact that Hēraklēs gathered an armada: a “mighty army” but also a “mighty navy”.

§4. In another retelling, as we read in Diodorus (4.17.1–4.18.22), Hēraklēs initially had to assemble a mighty army combined with a commensurately mighty navy in order to accomplish the Labor of rustling the cattle of Geryon in the Far West. At §5 in TC VIII, Classical Inquiries 2019.09.13, I already noted the implications of this spectacular expedition. Hēraklēs here is serving as a generalissimo for Eurystheus, king of Mycenae and high king of the Mycenaean Empire, by virtue of leading a mighty army combined with a mighty navy—I referred to these armed forces as an “armada” at §1.1.3 in TC IV, Classical Inquiries 2019.08.15.

In another article Nagy mentions the Labors and the sub-Labors of Hēraklēs: one of them, Labor 10, concerns the capture, with an army and a fleet, of the Cattle of Geryon, with several sub-Labors:

- sub-Labor 7 where he prepares an army and a fleet for his expedition to capture the Cattle of Geryon (Labor 10) and

- the sub-Labor when he sails west with his armada and sets up the Pillars of Hēraklēs.[3]

Diodorus Siculus (90–30 BCE) provides an account of these pillars, which were built at the narrowest point of the modern Strait of Gibraltar:

When Heracles arrived at the farthest points of the continents of Libya and Europe which lie upon the ocean, he decided to set up these pillars to commemorate his campaign. And since he wished to leave upon the ocean a monument which would be had in everlasting remembrance, he built out both the promontories, they say, to a great distance; consequently, whereas before that time a great space had stood between them, he now narrowed the passage, in order that by making it shallow and narrow he might prevent the great sea-monsters from passing out of the ocean into the inner sea, and that at the same time the fame of their builder might be held in everlasting remembrance by reason of the magnitude of the structures. Some authorities, however, say just the opposite, namely, that the two continents were originally joined and that he cut a passage between them, and that by opening the passage he brought it about that the ocean was mingled with our sea.[4]

Diodorus Siculus concludes that on this question “it will be possible for every man to think as he may please”.

The Pillars are mentioned by many different Greek authors, such as by Plato, in the Phaedo:

Also I believe that the earth is very vast, and that we who dwell in the region extending from the river Phasis to the Pillars of Hēraklēs, [109b] along the borders of the sea, are just like ants or frogs about a marsh, and inhabit a small portion only, and that many others dwell in many like places.[5]

and by Pindar, in Nemean 3:

It is not easy to cross the trackless sea beyond the pillars of Heracles, which that hero and god set up as famous witnesses to the furthest limits of seafaring. He subdued the monstrous beasts in the sea and tracked to the very end the streams of the shallows, [5] where he reached the goal that sent him back home again, and he made the land known.[6]

Beyond this landmark was the trackless sea. Later, the Romans would use the expression “Non Plus Ultra” to indicate that the Mediterranean was fine and that nobody knew what was beyond the pillars of Hercules (the Roman name for Hēraklēs). In his travels towards the west, Hēraklēs also follows also the Phoenician tradition in which, around 814 BCE, settlers from Tyre founded Carthage. Their trade network stretched as far as modern Cádiz, and even beyond the Pillars of Melqart, named after a Phoenician god that is commonly identified with the Greek hero Hēraklēs:

I wishing to get clear information about this matter where it was possible so to do, I took ship for Tyre in Phoenicia, where I had learned by inquiry that there was a holy temple of Heracles. [2] There I saw it, richly equipped with many other offerings, besides two pillars, one of refined gold, one of emerald: a great pillar that shone at night.[7]

Figure 2: Picture of Atlas

Also interesting during the expedition of Hēraklēs is his interaction with Atlas. After the hero rescues Atlas’ daughters from pirates:

Atlas was so grateful to Heracles for his kindly deed that he not only gladly gave him such assistance as his Labor called for, but he also instructed him quite freely in the knowledge of astrology. For Atlas had worked out the science of astrology to a degree surpassing others and had ingeniously discovered the spherical nature of the stars, and for that reason was generally believed to be bearing the entire firmament upon his shoulders. Similarly in the case of Heracles, when he had brought to the Greeks the doctrine of the sphere, he gained great fame, as if he had taken over the burden of the firmament which Atlas had borne, since men intimated in this enigmatic way what had actually taken place.[8]

During that expedition it is said that Hēraklēs also sailed in a golden boat cup, as recounted by Apollodorus. In a rather comical episode. Hēraklēs, disliking the heat coming from the rays of the sun, shoots an arrow at the god. He does not seem to be in awe of gods at first!

As a tenth labor he was ordered to fetch the kind of Geryon from Erythia. ….So journeying through Europe to fetch the kine of Geryon he destroyed many wild beasts and set foot in Libya, and proceeding to Tartessus he erected as tokens of his journey two pillars over against each other at the boundaries of Europe and Libya. But being heated by the Sun on his journey, he bent his bow at the god, who in admiration of his hardihood, gave him a golden goblet in which he crossed the ocean. …And Hercules, embarking the kine in the goblet and sailing across to Tartessus, gave back the goblet to the Sun”…[9]

There is also an interesting note from the translator, Frazer, on this passage about the cup telling more about the boat cup:

…Athenaeus … quotes from the third book of Pherecydes as follows: “And Hēraklēs drew his bow at him as if he would shoot, and the Sun bade him give over; so Hēraklēs feared and gave over. And in return the Sun bestowed on him the golden goblet which carried him with his horses, when he set, through the Ocean all night to the east, where the Sun rises. Then Hēraklēs journeyed in that goblet to Erythia. And when he was on the open sea, Ocean, to make trial of him, caused the goblet to heave wildly on the waves. Hēraklēs was about to shoot him with an arrow; and the Ocean was afraid and bade him give over.” Stesichorus described the Sun embarking in a golden goblet that he might cross the ocean in the darkness of night and come to his mother, his wedded wife, and children dear.”[10]

What kind of boat is it? A circular one made of gold. Do we have other mentions of this type of boat in other myths? What we know is that according to the sources in Frazer’s note, Helios drove the chariot of the Sun across the sky each day to Earth-circling Oceanus and through the world-ocean returned to the East at night.

Then, traveling back home, from west to east, Hēraklēs leaves his fleet behind and is given solar attributes to speed-up his voyage. As depicted in figure 1, he sails across the sea in the cup-boat of the sun-god Helios. The hero wears a lion-skin cape and holds a club and bow in his hands. The sea is decorated with octopus and fish motifs. The symbolism of the octopus on may relate to the idea of regeneration after death, quite like the decoration on the Minoan clay coffins.

In the physical world, the “cup boat of Helios” is reminiscent of the Assyrian quffa, a riverboat that was operated on the Euphrates. Together with the references to Erytheia, the land “of the rosy morn”, there may be a connection to the Middle East that we do not know of.

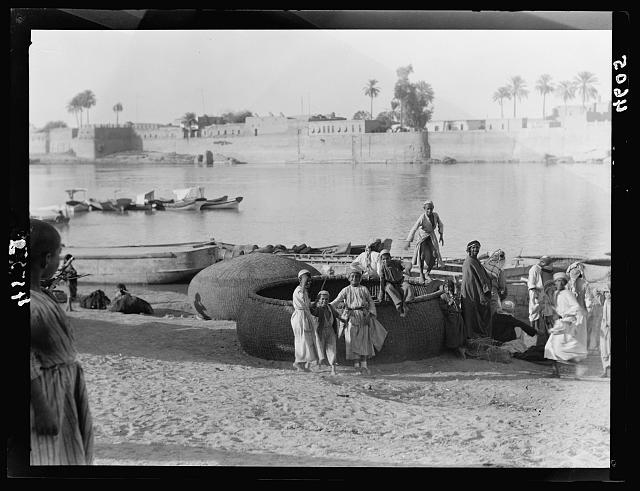

Figure 3: Baghdad. River scenes on the Tigris. Ghuffas/coracles in dry dock for re-tarring – circa early 1930’s

Using willow of the Armenians, the Assyrians made their quffa; the round coracle of the Euphrates:

Figure 4: patchwork hide boat with a round form: 700 BCE bas relief of Sennacheri.

Also Herodotus knows about these round boats from Babylon:

I am going to indicate what seems to me to be the most marvellous thing in the country, next to the city itself. Their boats which ply the river and go to Babylon are all of skins, and round. [2] They make these in Armenia, higher up the stream than Assyria. First they cut frames of willow, then they stretch hides over these for a covering, making as it were a hold; they neither broaden the stern nor narrow the prow, but the boat is round, like a shield. They then fill it with reeds and send it floating down the river with a cargo; and it is for the most part palm wood casks of wine that they carry down. [3] Two men standing upright steer the boat, each with a paddle, one drawing it to him, the other thrusting it from him. These boats are of all sizes, some small, some very large; the largest of them are of as much as five thousand talents1 burden. There is a live ass in each boat, or more than one in the larger.[11]

To continue examining the “nautical” labors of Hēraklēs, he, like Odysseus, suffers many ordeals from the sea. They both have to perform āthloi, ‘labors’ and they both use bow and arrows. They are also strong and mighty men.

But Hēraklēs is a hero from a prior generation, and is a “model for all heroes”[12]. He is mentioned in the Iliad several times.

Firstly he came to conquer Troy for the first war with only six ships.

Far other was Hēraklēs, my own brave and lion-hearted father, [640] who came here for the horses of Laomedon, and though he had six ships only, and few men to follow him, destroyed the city of Ilion and made a wilderness of her highways.[13]

Then in Iliad 14, like Odysseus, he had to face the wrath of a goddess and suffered in a terrible sea storm.

Then Sleep answered, “Hera, great queen of goddesses, daughter of mighty Kronos, I would lull any other of the gods to sleep without compunction, not even excepting the waters of Okeanos [245] from whom all of them proceed, but I dare not go near Zeus, nor send him to sleep unless he bids me. I have had one lesson already through doing what you asked me, [250] on the day when Zeus’ mighty son Hēraklēs set sail from Ilion after having sacked the city of the Trojans. At your bidding I suffused my sweet self over the mind of aegis-bearing Zeus, and laid him to rest; meanwhile you hatched a plot against Hēraklēs, and set the blasts of the angry winds beating upon the sea, till you took him [255] to the goodly city of Cos away from all his friends. Zeus was furious when he awoke, and began hurling the gods about all over the house; he was looking more particularly for myself, and would have flung me down through space into the sea where I should never have been heard of any more, had not Night who cows both men and gods protected me.[14]

Hēraklēs was also one of the heroes who followed Jason and the Argonauts in the famous naval expedition, recounted by Apollodorus in his Argonautica. At that time, before the war of Troy, he was among the great heroes to come to the help of Jason. He came with his young companion Hylas who oversaw his bow and arrows. Hēraklēs was even asked to be the leader of the expedition but refused the offer.

At some point during the voyage, he breaks an oar, as he is “ploughing” the sea.

Heracles, as he ploughed up the furrows of the roughened surge, broke his oar in the middle. And one half he held in both his hands as he fell sideways, the other the sea swept away with its receding wave. And he sat up in silence glaring round; for his hands were unaccustomed to the idle.[15]

Then he decides to go into a forest to find some wood to make another one.

[1187] But the son of Zeus having duly enjoined on his comrades to prepare the feast took his way into a wood, that he might first fashion for himself an oar to fit his hand. Wandering about he found a pine not burdened with many branches, nor too full of leaves, but like to the shaft of a tall poplar; so great was it both in length and thickness to look at. And quickly he laid on the ground his arrow-holding quiver together with his bow and took off his lion’s skin. And he loosened the pine from the ground with his bronze-tipped club and grasped the trunk with both hands at the bottom, relying on his strength; and he pressed it against his broad shoulder with legs wide apart; and clinging close he raised it from the ground deep-rooted though it was, together with clods of earth. And as when unexpectedly, just at the time of the stormy setting of baleful Orion, a swift gust of wind strikes down from above, and wrenches a ship’s mast from its stays, wedges and all; so did Heracles lift the pine. And at the same time he took up his bow and arrows, his lion skin and club, and started on his return.[16]

The passage describing his search for the perfect beam and the enormous task of cutting down trees is in a way similar to what Odysseus does in Odyssey 5, when he builds his improvised vessel.

He cut down twenty trees in all and adzed them smooth, [245] squaring them by rule in good workmanlike fashion…”[17]

Both heroes are strong and are able to find the perfect beam to build a boat or oars to pursue their sea voyages and face ordeals.

Like other great epic heroes they were destined to get a kleos for ever, especially Hēraklēs whose name means “He who has the kleos of Hera”. While Odysseus has his kingdom to go back to, Hēraklēs will never have a kingdom of his own—but he will become immortal.

Notes

[1] Heracles’s tenth labor: The Cattle of Gerion. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ Attic red-figured kylix, made in Athens, attributed to Douris, about 500-450 BC, from Vulci, Etruria, Rome Vatican Museums, Museo Gregoriano Etrusco

[2] “Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology XII, Hēraklēs at his station in Mycenaean Tiryns”

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thinking-comparatively-about-greek-mythology-xii-herakles-at-his-station-in-mycenaean-tiryns/

[3] “Thinking comparatively about Greek mythology IV, Reconstructing Hēraklēs backward in time”

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thinking-comparatively-about-greek-mythology-iv-reconstructing-herakles-backward-in-time/

[4] Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History 4.18.4–4.18.5. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. 1935.

Online at LacusCurtius

[5] Phaedo 109a–109b, Sourcebook.

The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2019.08.13. Available online at CHS.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

[6] Pindar, Nemean 3.20–26, translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien

Online at Perseus

[7] Herodotus Histories 2.44.1–2, translated by A.D. Godley.

Online at Perseus

[8] Diodorus Siculus, The Library of History 4.27.4–4.27.5, translated by C. H. Oldfather.

Online at LacusCurtius.

[9] Apollodorus The Library 2.5.10, translated by Sir James George Frazer, Perseus.

Online at Perseus.

[10] Footnote 7 by James Frazer to his translation of Apollodorus Library 2.5.10

Online at Perseus.

[11] Excerpt from Herodotus, Histories 1.194.1–1.194.3, Translated by A.D. Godley.

Online at Perseus.

[12] “Hour 1. The Homeric Iliad and the glory of the unseasonal hero,” in

Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA: 2013. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[13] Homeric Iliad 5.638–642, Sourcebook.

[14] Homeric Iliad 14.242–259, Sourcebook.

[15] Argonautica 1.1167–1171, translated by R.C. Seaton. 1912, Cambridge, MA.

Online at Perseus under PhiloLogic

[16]> Argonautica 1.1187, translated by R.C. Seaton.

[17] Odyssey 5.244–245, Sourcebook

Image credits

Figure 1: Heracles’s tenth labor: The Cattle of Gerion. Attic red-figured kylix, made in Athens, attributed to Douris, about 500-450 BC, from Vulci, Etruria, Rome Vatican Museums, Museo Gregoriano Etrusco

Photo: Egisto Sani https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ via Flickr

Figure 2: Atlas and Hercules carrying a sphere. Ivory, 17th century.

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/deed.en via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 3: Baghdad. River scenes on the Tigris. Ghuffas/coracles in dry dock for re-tarring – circa early 1930’s.

Library of Congress. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection. No known copyright restrictions

Figure 4: patchwork hide boat with a round form: 700 BCE bas relief of Sennacheri.

Public domain, Freshwater and Marine Image Bank, University of Washington. via Wikimedia Commons.

Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images and online texts accessed December 2019.

___

Hélène Emeriaud and Rien are members of Kosmos Society.