The spectator on the aft deck

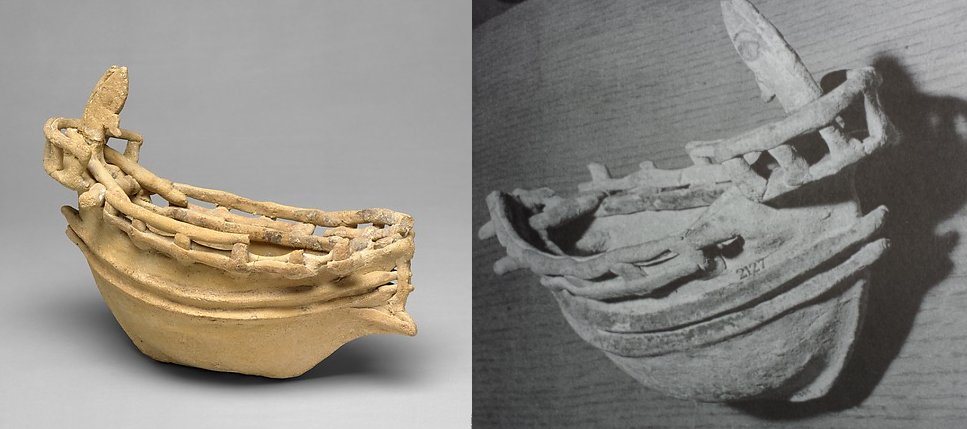

A clay model found in a tomb at Amathos[1] tells us the story of a man who comfortably sits on the back of his ship without a helm, having such a clear vision over the well-built ship—and where it is going to—that we could call it a modeled scene of a theōriā: the figure being a spectator who looks with his eyes and his mind: a state pilgrim [theōros]. We do not know what his role, his activities, will be, both on the journey and at the sanctuary[2].

The ship is a theōris built to take the sacred delegate outside of his own territory. He is the Homeric pilot who is lost at sea and finally finds his bearings and reaches home. He directs not only the ship but also, metaphorically, the community that is the ship. Possibly he is the kubernētēs, the governor who directs the ‘ship of state’[3].

Alternatively, the helmsman, who looks so balanced [sōphrōn] is the keen observer who recognizes Dionysus for what he is and who is therefore saved by the god Dionysus himself from being transformed into a dolphin:

Meanwhile the steersman took note right away …. As for the steersman—he [= Dionysus] took pity on him, holding him back [from leaping overboard]. He [= Dionysus] caused it to happen that he [= the steersman] became the most blessed of all men[4].

Another indicator [sēma] for the meaning of this clay model may be the absence of oarsmen or sails: the ship moves by the power of thought and observation of the helmsman, who does not even have to touch the rudder[5], but keeps his arms resting on the gunwales. Odysseus, when talking about the Phaeacians, says: “They are a sea-faring folk, and sail the seas by the grace of Poseidon[6] in ships that glide along like thought, or as a bird in the air.”[7]

The model shows transverse beams protruding from the quarters of the ship. The extremities of the beams are called “catheads”[8] [epōtides] and are mentioned by Euripides:

There we saw a Hellene ship, winged with ready blade for the stroke, and at the oar-locks were fifty rowers with their oars; the two youths stood by the stern, freed from their chains. Some were holding the prow in place with poles; others were fastening the anchor from the cat-heads [epōtides]; others were drawing the stern-cables through their hands and making haste to let down the ladders into the sea for the strangers.[9]

The catheads on the raised aft deck [ikria] provide support for the pennants, or straps, which are used to control the tillers of the quarter rudders. This idea can even take the shape of housings for the rudder [pēdálion] as we see in Figure 3, showing an integration of the epōtides and the steering bench. On later, Hellenistic ships, these extensions were called parexeiresia[10]: outside the eiresia, the oarbank. On Homeric ships the raised aft deck could have a width of seven feet [eptapódin, íkria; Iliad 15.729]

The next ship model, shown below, is kept at the Thalassa, Agia Napa municipal Museum at Cyprus. It models the type of vessels used around 600–480 BCE, especially in between Amathus—on the southern coast of Cyprus—and Egypt.

The model is slightly more detailed than the ones represented before and features what seems to be a raised and ornamented bow shape. The forebody shows the catheads for the ground-tackle. The middle of the stern and the ship as far as the prow is undecked [asanidon][11]. The aftbody of the model shows again a single figure, standing on the poop-deck, not evidently involved in the operation of the ship. The width of the poop-deck with epōtides exceeds the width of the ship.

The histopedē (mast step)

The word for “mast”, histos, is used for the ship’s mast of Odysseus. The related word is histopedē, which indicates a construction placed at the bottom of the ship structure into which the lowest part of the mast fits: a mast step. The third word is mesodme; a tie-beam with a hole or notch in it which centers over the mast step. The masts were lowered in aft direction, as we do today, so the notch in the mesodme was open towards aft and closed towards forward.

Figure 4: Terracotta model of a merchant galley from Cyprus (top view).

For visualizing all this we can look at the terracotta model of a thirty-oared merchant ship from Amathos, Cyprus, dated about 600–500 BCE. The ship model is kept in the collection of the British Museum. The waterlines in the forebody are slender. The aftbody with aft castle is full. Cross-beams span the full and deep hull and the most central beam represents the tie-beam [mesodme], the brackets of which are open in aft direction. This agrees with the event of Odyssey 12.411 in which the mast falls not forward, as you would expect in a ship that can sail before the winds only, but towards aft, upon the head of Baius[12], the unfortunate helmsman.

Lionel Casson[13] describes the mesodme as “a carling, running fore and aft between two thwarts amidships, that had a hole or notch in it which centered over the mast step”. It is translated by LSJ as “tie-beam” and within the CHS source text[41] it is convincingly introduced as a “socket in the cross plank”.

Underneath the tie-beam, mounted to the bottom of the ship, we can see the mast step [histopedē], fitted with a slender vertical casing to accommodate the lowest part of the mast. The word histopedē is commonly as “a piece of wood” and within the context of the Odyssey[15] it is suitably translated as “mast step”; a construction placed at the bottom of the ship structure into which the lowest part of the mast is mounted. It is from this uncomfortable low view point, the top of the vertical casing, that Odysseus watches the Sirens[16].

Protonos and its antonym, epitonos, respectively indicate the forestay and the backstay of a mast. According to Iliad 1.434 the mast is let down by slackening the forestays and settled into the mast crutch [histodokē], which consequently must be in the aft of the ship. Next the mast is fastened with the forestays (Odyssey 2.425). The epitonos is only mentioned once, in Odyssey 12.423, but not in the context of raising or lowering the mast. Apparently the epitonos is the standing rigging, tensioned by the running rigging, which are the protonoi. The forestays [protonoi] are always described in the plural form, indicating that there is “a pair of forestays” and Apollonius of Rhodes [1.563] describes that there is one on either side of the bow, which would allow them to absorb some side-forces too.

Figure 5 shows the mast foot and aft-body of the 9th-century Gokstad Viking ship. The lower part of the mast is locked into the mast foot by a wedge, which indicates that the mast of this forty-oared Viking Ship was lowered in a similar way as the mast of the ancient Greek ship, namely by lowering it aft, by slackening of the forestay. The Viking ship is wider and less deep than the full block merchant galley from Cyprus, making the application of the mesodme impractical.

Previously: The Modeled Ship | Part 1: The gift of Kinyras, and the honeycomb boats

Notes

[1] The Cesnola Collection, Ancient Art from Cyprus, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

[2] Ian Rutherford: State Pilgrims and Sacred Observers in Ancient Greece, University of Reading, (2014).

[3] “The Ship of State” is a metaphor put forth by Plato in Book VI of the Republic (488e–489d). Leonard Cohen’s song “Democracy” contains the line “Sail on. Sail on, o mighty ship of state. (p. 12). In the British TV series Yes, Minister, Sir Humphrey Appleby pointed out that “the Ship of State is the only ship that leaks from the top”.

[4] Homeric Hymn (7) to Dionysus. Translated by Gregory Nagy. Sourcebook.

[5] “Of all who lived pure, he was purer than a steering oar, even though the steering oar is always in the sea.” (Soudas 1.30. no. 2810.10f)

[6] “Hail, Poseidon, Holder of the Earth, dark-haired lord! O blessed one, be kindly in heart and help those who voyage in ships!” ([Homeric Hymn 22 to Poseidon 6–7)

[7] Odyssey 7.34–37 Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray. Published under a Creative Commons License 3.0.

[8] In the expression “cathead”, the “head” is the extremity of the beam that supports the set of sheaves through which a ‘cat fall’ runs. The assembly of beam, sheaves, and cat fall, forms a lifting tackle.

[9] Euripides Iphigenia in Tauris 1345–1352; translated by Robert Potter, on Perseus.

[10] Based on J. S. Morrison, Joseph Francis Coates, J. F. Coates, N. B. Rankov. The Athenian Trireme: The History and Reconstruction of an Ancient Greek Warship p161. The Greek word parexeiresia suggests some part of the ship concerned with pulling the oars [eiresia] outboard [ex-] and alongside [par-]. Morrison mentions it in the context of the oar system of triērēs.

[11] Casson Lionel. 2014. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World p151: Undecked: ‘asanidon’. The covered area along either side of the hull is called the ‘deck’ [katastroma] or the ‘platform’ [thranos] or the ‘planking’ [sanidomata]

[12] Baius and Misenus, two of the companions of Odysseus. (Strabo Geography 1.2.18)

[13] Casson Lionel. 2014. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton University Press.

[14] Odyssey 2.424.

[15] Odyssey 12.51, 62, 179.

[16] “have them bind you in the swift ship, hands and feet, upright in the step of the mast [histopedē], and have the ends of the ropes be fastened to the mast itself”. (Odyssey 12.50–51)

Bibliography

Anonymous. 1914. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Casson, Lionel. 2014. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Princeton University Press. Available online at Project MUSE, Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore.

Delivorrias, A. ea. 1987. Griekenland en de zee. Ministry of Culture of Greece

Homeric Iliad Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray. Published under a Creative Commons License 3.0.

Homeric Odyssey. Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray. Published under a Creative Commons License 3.0.

Plato. The Republic translated by Paul Shorey. 1969. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Rutherford, Ian. 2014. State Pilgrims and Sacred Observers in Ancient Greece, University of Reading, UK.

Soudas 1.30. no. 2810.10f

Image credits

Figure 1: Terracotta model of a ship. ca. 600–480 BCE. The Cesnola Collection, Purchased by subscription, 1874–76. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York.

Figure 2: Merchantman from Cyprus, 6th BCE, Casson Lionel. 2014. Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World. Illustration 94.

Figure 3: Terracotta ship model, Cyprus, 600–480 BCE. Treasures of Thalassa Museum, Ayia Napa. Author Claus Ableiter. licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Figure 4: Terracotta model of a merchant galley from Cyprus. British Museum. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Figure 5: Gokstad Viking ship: mast foot detail. Photo by author.

First published July 17, 2018

Biography

Rien is a participant of the Kosmos Society.