In the previous posts in this series we looked at descriptions of hair for males and for females. This time we look at some examples of how hair features in ritual events as depicted in the texts.

Ritual offering of hair

Achilles and his companions cut their hair and offer it in commemoration at the funeral of Patroklos:

In the midst of them his comrades bore Patroklos [135] and covered him with the locks of their hair [thrix] which they cut off [keirō] and threw upon his body. Last came radiant Achilles with his head bowed for sorrow, so noble a comrade was he taking to the house of Hādēs.

When they came to the place of which Achilles had told them they laid the body down and built up the wood. [140] Radiant swift-footed Achilles then turned his thoughts to another matter. He went a space away from the pyre, and cut off the yellow [xanthos] flowing lock [khaitē] which he had let grow for the river Sperkheios. He looked all sorrowfully out upon the dark [oinops] sea [pontos], and said, “Sperkheios, in vain did my father Peleus vow to you [145] that when I returned home to my loved native land I should cut off [keirō] this lock [komē] and offer you a holy hecatomb; fifty she-goats was I to sacrifice to you there at your springs, where is your grove and your altar fragrant with burnt-offerings. Thus did my father vow, but you have not fulfilled the thinking [noos] of his prayer; [150] now, therefore, that I shall see my home no more, I give this lock [komē] as a keepsake to the hero Patroklos.”

As he spoke he placed the lock [komē] in the hands of his dear comrade, and all who stood by were filled with yearning and lamentation.

Iliad 23.134–153, adapted from Sourcebook[1]

This custom seems to have been continued, or this myth used as an explanation for the practice of cutting and offering hair.

Pausanias writes about the ritual that takes place at Trozen at a shrine to Hippolytus. Young virgin girls cut a lock of hair and offer it to the cult hero.

[2.32.1] Hippolytus son of Theseus has a most prominent sacred space [temenos] set aside for him [in Trozen]. And there is a shrine [nāos] inside this space, with an archaic statue [inside it]. They say that Diomedes made these things and, on top of that, that he was the first person to make sacrifice [thuein] to Hippolytus. The people of Trozen have a priest of Hippolytus, and this priest is consecrated [hieroûsthai] as a priest for the entire duration of his life. There are sacrifices [thusiai] that take place at a yearly festival, and among the ritual actions that the people do [drân], I describe this event that takes place [at the festival]: each and every virgin girl [parthenos] in the community cuts off a lock of her hair [plokamos] for him [= Hippolytus] before she gets married, and, having cut it off, each girl ceremonially carries the lock to the shrine [nāos] and deposits it there as a dedicatory offering.

Pausanias 2.32.1–2, adapted from Sourcebook

Pausanias also provides several other passages relating to stories featuring hair or that relate to various customs of offering hair:

{1.19.4} Behind the Lyceum is a monument of Nisos, who was killed while king of Megara by Minos, and the Athenians carried him here and buried him. About this Nisos there is a legend. His hair [thrix, pl.] on his head [kephalē], they say, was red [porphureos], and it was fated that he should die on its being cut off [apo-keirō]. When the Cretans attacked the country, they captured by assault the other cities of the region of Megara, but Nisaia, in which Nisos had taken refuge, they besieged. The story says how the daughter of Nisos, falling in love here with Minos, cut off [apo-keirō] her father’s hair [thrix, pl.].

1.19.4, adapted from A Pausanias Reader, Scroll I. Attica [2]

{8.20.2} … Leukippos fell in love with Daphne, but despaired of winning her to be his wife by an open courtship, as she avoided all the male sex. The following trick occurred to him by which to get her. Leukippos was growing [trephō] his hair [komē] long for the river Alpheios.

{8.20.3} Braiding [plekō] his hair [komē] as though he were a girl, and putting on woman’s clothes, he came to Daphne and said that he was a daughter of Oinomaos, and would like to share her hunting. As he was thought to be a girl, surpassed the other girls in nobility of birth and skill in hunting, and was besides most assiduous in his attentions, he drew Daphne into a deep friendship.

{8.20.4} The poets who sing of Apollo’s love for Daphne make an addition to the tale; that Apollo became jealous of Leukippos because of his success in his love. Forthwith Daphne and the other girl conceived a longing to swim in the Ladon, and stripped Leukippos in spite of his reluctance. Then, seeing that he was not a girl, they killed him with their javelins and daggers.8.20.2–4, adapted from A Pausanias Reader, Scroll VIII. Arcadia

{7.5.5} You would be delighted too with the sanctuary of Hēraklēs at Erythrai and with the temple of Athena at Priene, the latter because of its image and the former on account of its age. The image is like neither the Aeginetan, as they are called, nor yet the most ancient Attic images; it is absolutely Egyptian, if ever there was such. There was a wooden raft, on which the god set out from Tyre in Phoenicia. The reason for this we are not told even by the Erythraeans themselves.

{7.5.6} They say that when the raft reached the Ionian sea it came to rest at the cape called Mesate (Middle) which is on the mainland, just midway between the harbor of the Erythraeans and the island of Chios. When the raft rested off the cape the Erythraeans made great efforts, and the Chians no less, both being keen to land the image on their own shores.

{7.5.7} At last a man of Erythrai (his name was Phormion) who gained a living by the sea and by catching fish, but had lost his sight through disease, saw a vision in a dream to the effect that the women of Erythrai must cut off [apo-keirō] their locks [komē, pl.], and in this way the men would, with a rope woven [plekō] from the hair [thrix, pl.], tow the raft to their shores. The women of the citizens absolutely refused to obey the dream;

{7.5.8} but the Thracian women, both the slaves and the free who lived there, offered themselves to be shorn [apo-keirō]. And so the men of Erythrai towed the raft ashore. Accordingly no women except Thracian women are allowed within the sanctuary of Hēraklēs, and the rope of hair [thrix, pl.] is still kept by the natives. The same people say that the fisherman recovered his sight and retained it for the rest of his life.7.5.5–8, adapted from A Pausanias Reader, Scroll VII. Achaea

Women’s lament

In the previous post we discussed the elaborate hairstyles and adornments of women’s hair, and how they feared being dragged away by their hair. In lament, these come together in a stylized ritual action. For example:

[460] She [= Andromache] rushed out of the palace, same as a maenad [mainas], 461 with heart throbbing. And her attending women went with her. 462 But when she reached the tower and the crowd of warriors, 463 she stood on the wall, looking around, and then she noticed him. 464 There he was, being dragged right in front of the city. The swift chariot team of horses was [465] dragging him, far from her caring thoughts, back toward the hollow ships of the Achaeans. 466 Over her eyes a dark night spread its cover, 467 and she fell backward, gasping out her life’s breath [psūkhē]. 468 She threw far from her head [kras] the splendid adornments that bound her hair [desma, pl.] 469 —her frontlet [ampux], her snood [kekruphalos], her plaited headband [anadesmē], [470] and, to top it all, the headdress [krēdemnon] that had been given to her by golden Aphrodite 471 on that day when Hector, the one with the waving plume on his helmet [koruthaiolos], took her by the hand and led her 472 out from the palace of Eëtion, and he gave countless courtship presents. 473 Crowding around her stood her husband’s sisters and his brothers’ wives, 474 and they were holding her up. She was barely breathing, to the point of dying. [475] But when she recovered her breathing and her life’s breath gathered in her heart, 476 she started to sing a lament in the midst of the Trojan women.

Iliad 22.460–476, adapted from Sourcebook

In this scene she is acting out her grief, loss of control, and fear about being taken away.

In Euripides’ play, Electra has shaved her head like a Scythian, because she is in mourning. Does this indicate how she has adopted a different custom as part of her alienation and exile?

Electra

Well then, you see first of all how withered my body is.

Orestes

[240] Yes, so wasted with sorrow that I sigh for it.

Electra

And my head [kras] and hair [plokamos], close shaven as if by a Scythian’s razor [xuros].

Euripides Electra 239–241, adapted from translation by E.P. Coleridge, on Perseus

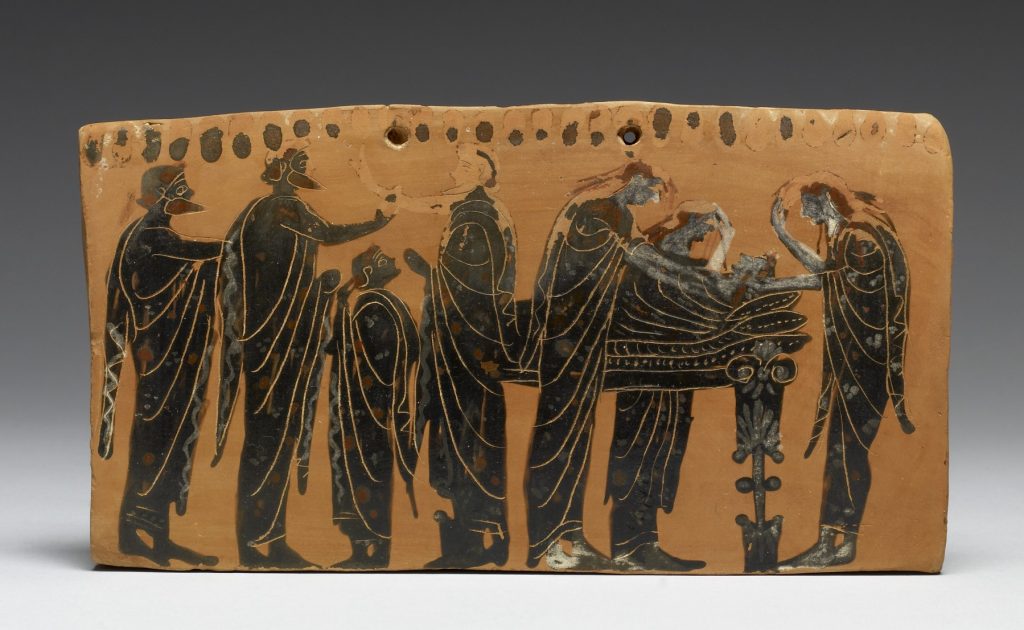

Or perhaps this is a formalized version of the action of tearing out the hair at a funeral, as depicted on the image on this plaque:

Recognition

In several tragedies, hair is used as a means of recognition: the ἀναγνώρισις [anagnôrisis]. In Aeschylus Libation Bearers, Electra will realize that her brother Orestes is back when she sees the lock of hair at the tomb of their father. First we have Orestes who deposits two locks of hair, then later Electra discovers the hair and recognizes it because it looks like hers.

At the tomb of Agamemnon. Orestes and Pylades enter.

Orestes

[Look, I bring] a lock of hair [plokamos] to Inakhos [=the river god of Argos] in compensation for his care, and here, a second, in token of my grief [penthos]. For I was not present, father, to lament your death, nor did I stretch forth my hand to bear your corpse. …Electra discovers the lock of Orestes’ hair.

Electra

My father has by now received the libations, which the earth has drunk. 165 But take your share of this startling utterance [mūthos].

Chorus

Speak—but my heart is dancing with fear.

Electra

I see here a lock [bostrukhos] cut [tomaios] as an offering for the tomb.

Chorus

A man’s, or a deep-girdled maiden’s?

Electra

170 That is open to conjecture—anyone may guess.

Chorus

How then? Let my age be taught by your youth.

Electra

There is no one who could have cut [keirō] it but myself.

Chorus

Then they are enemies [ekhthroi] who thought it fit to express grief [penthos] with a lock of hair [thrix].

Electra

And further, in appearance it is very much like…

Chorus

175 Whose lock [etheira pl.]? This is what I would like to know.

Electra

It is very much like my own in appearance.

Chorus

Then can this be a secret offering from Orestes?Aeschylus Libation Bearers 6–7, 164–177, adapted from Sourcebook

In Sophocles Electra and in Euripides Electra also we have a scene with the hair, but in Euripides, Electra refuses to use this means of recognition. Euripides seems to make fun of Aeschylus’ scene: Electra is finding it ridiculous that two locks might indicate people from the same family.

Old man

… [520] Go look to see if the color of the cut [kourimos] lock [khaitē] is the same as the hair on your head [komē], putting it to your own hair [thrix]; it is usual for those who have the same paternal blood to have a close resemblance in many features.Electra

Old man, your words are unworthy of a wise man, [525] if you think my own brave brother would come to this land secretly for fear of Aegisthus. Then, how will a lock [plokos] of hair [khaitē] correspond, the one made to grow in the wrestling schools of a well-bred man, the other, feminine [thēlus], smoothed by combing [ktenismos]? No, it is impossible. [530] But you could find in many people hair [bostrukhos] very similar, although they are not of the same blood, old man.

Euripides Electra 520–532, adapted from translation by E.P. Coleridge, on Perseus

What other passages have you found that describe hair featuring in a ritual? Who offers hair and under what circumstances? What other activities are involved? What is the role of the river gods? Do customs vary in different regions or over time? What other examples are there of hair featuring in recognition scenes [anagnôrisis]? Join the discussion in the Forum!

Previously:

part 1 | Male hair: descriptions

part 2 | Female hair: descriptions

Next:

part 4 | Epithets with hair

Glossary

Terms for hair and descriptions featured in this post (summarized from definitions in LSJ and/or Autenrieth, on Perseus, or from Montanari, Franco The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek.)

apo-keirō ‘clip, cut off, shear; sever; slay’

bostrukhos ‘curl or lock of hair’

desma ‘bonds; a woman’s head-band’

etheira ‘hair of the head; mane; horsehair crest’

khaitē ‘long flowing hair; mane’

keirō ‘cut off, crop, shear’

kephalē ‘head’

komē ‘hair of the head’

koruthaiolos ‘shaking crest of the helmet’

kourismos ‘of, for cutting hair’

kras ‘head’

ktenismos ‘combing’

plekō ‘to plait, twist; devise, contrive; compound’

plokos ‘lock of hair, a braid, curl’

plokamos ‘lock or braid of hair’

porphureos ‘heaving, gushing; purple; bright-red, rosy, flushing’

thēlus ‘female; delicate’

thrix ‘the hair of the head; a single hair’

tomaios ‘cut, cut off’

trephō ‘rear, nourish; let grow, cherish, foster’

xanthos ‘reddish-yellow, blond, auburn (of hair); sorrel or cream-colored (of horses)’

xuros ‘razor’

Note: Greek terms incorporated in the quoted passages have been taken from the Greek editions of the texts on Perseus

References

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[2] Description of Greece: A Pausanias Reader. Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Greta Hawes and Gregory Nagy.

Image credits

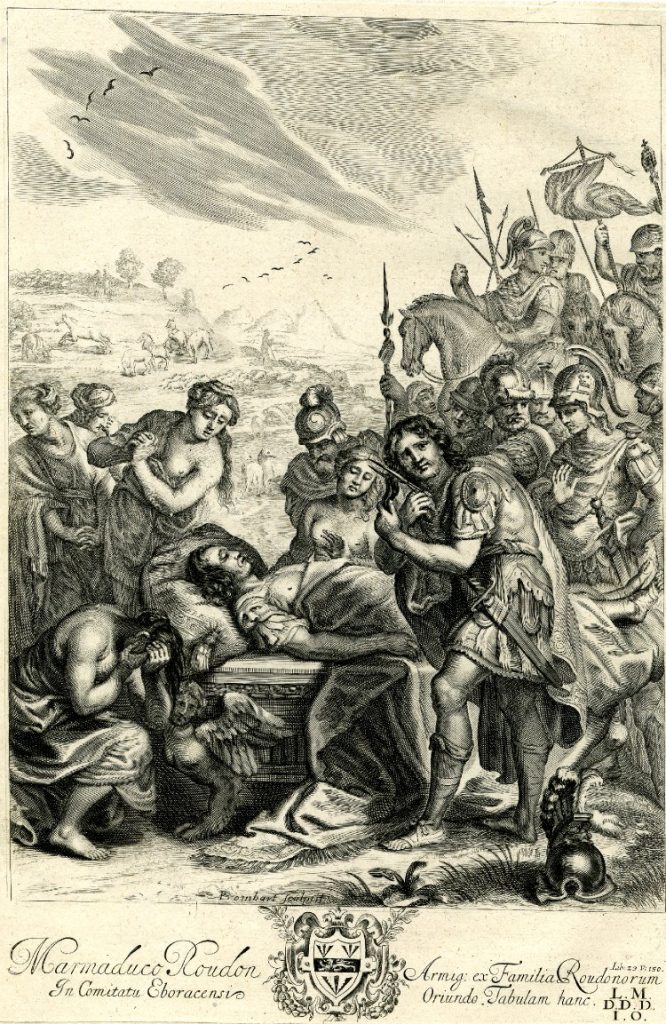

Johan Tobias Sergel, “Achilles and his companions carrying dead body of Patroclus to funeral pyre, Achilles laying lock of his hair on body. c.1766 Etching” 2002,0127.17, Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, Attribution: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Obsequy of Patroclus “illustration for Ogilby’s ‘Homer his Iliads Translated Adorn’d with Sculpture, and Illustrated with Annotations’, book 23 (London, Thomas Roycroft, 1660). c.1660 Engraving”, 1856,1105.58, Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, Attribution: © The Trustees of the British Museum

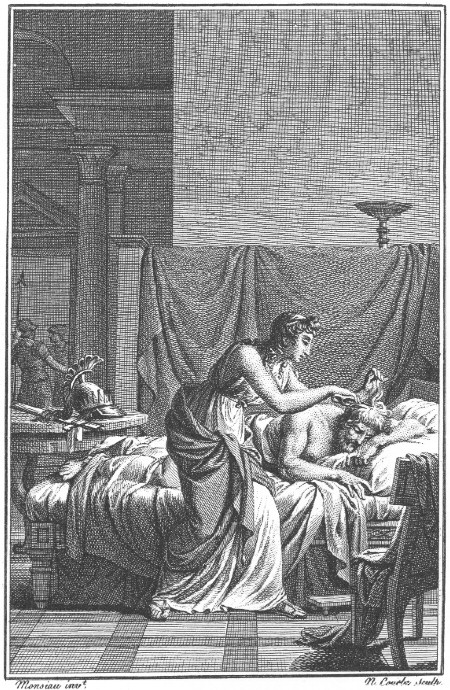

Nicolas-André Monsiau Scylla and Nisus. Scylla cutting her father’s purple hair. Paris, 1806, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Glea Painter, “”prothesis” scene, the lying-in-state of the deceased on a bed, surrounded by his family members, some of whom tear their hair in mourning.” Black-figure Plaque (Pinax), Greek c 500–c 450 BCE(?) 48.225, The Walters Art Museum, Creative Commons CC0

Bibi Saint-Pol (photo) Choephoroi Painter: Orestes, Electra and Hermes at the tomb of Agamemnon, Side A of a lucanian red-figure pelike, c 380–370 BCE, K 544, Louvre Museum, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from Sailko (photo) Jacques-Louis David Andromache Mourning Hector, Louvre Museum, Creative Commons CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

_________________

Hélène Emeriaud, Janet Ozsolak, and Sarah Scott are members of the Kosmos Society.