But the mane [khaitā]

of the other one, my kinswoman

Hagesikhora, blossoms [epantheō] on her head

like imperishable gold [khrusos].

…

She is Hagesikhora.

But whoever is second to Agido in beauty,

let her be a Scythian horse running against a Lydian one.

…

It is true: all the royal purple

65 in the world cannot resist.

No fancy snake-bracelet,

made of pure gold, no headdress

from Lydia, the kind that girls

with tinted eyelids wear to make themselves fetching.

70 No, even the hair [komē, pl.] of Nanno is not enough.Alcman Parthenion, 51–54, 57–59, 64–70, adapted from Sourcebook[1]

In the descriptions of women’s hair we see how it is depicted as an object of attraction for others. For women themselves they can use this to their advantage as a means of seduction.

Hera is well aware of how she looks when she prepares to lure Zeus:

[170] She cleansed all the dirt from her fair body with ambrosia, then she anointed herself with olive oil, ambrosial, very soft, and scented specially for herself—if it were so much as shaken in the bronze-floored house of Zeus, the scent pervaded the universe of heaven and earth. [175] With this she anointed her delicate skin, and when she had combed [pekō] her hair [khaitē, pl] then she plaited [plekō] the fair [kalos, pl.] ambrosial locks [plokamos, pl.] that flowed in a stream of golden [phaeinos, pl.] tresses from her immortal head. She put on the wondrous robe which Athena had worked for her with consummate art, and had embroidered with manifold devices; [180] she fastened it about her bosom with golden clasps, and she girded herself with a girdle that had a hundred tassels: then she fastened her earrings, three brilliant pendants with much charm radiating from them, through the pierced lobes of her ears, [185] and threw a lovely new veil over her head.

Iliad 14.170–186, adapted from Sourcebook

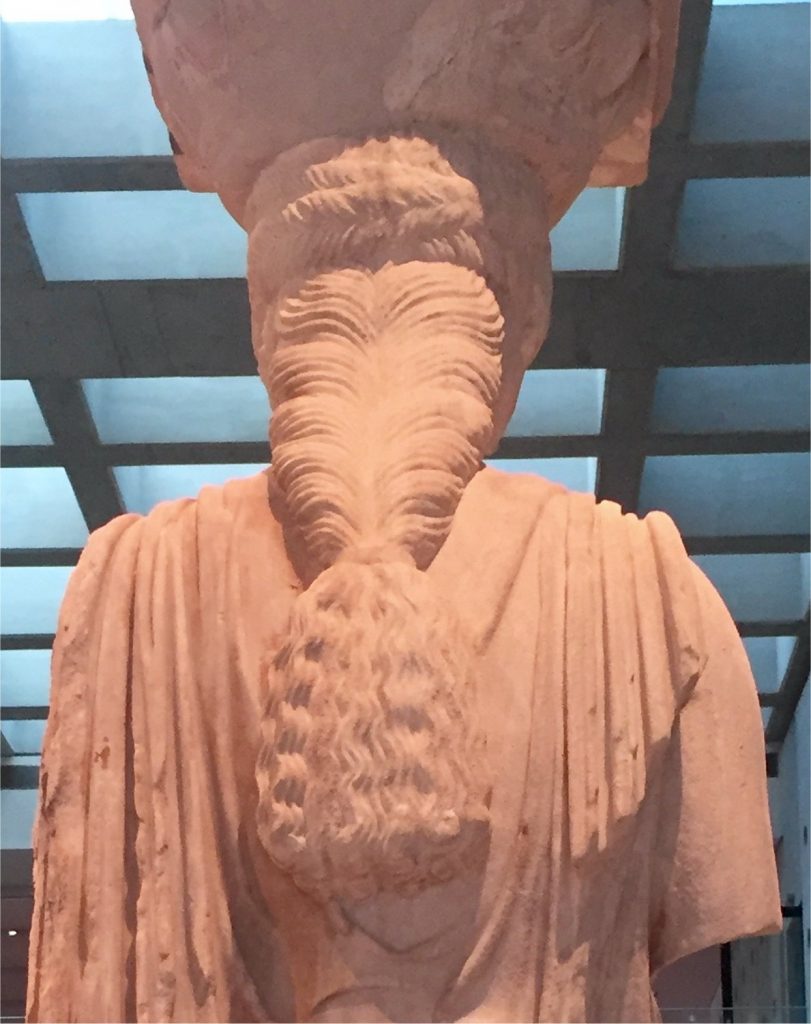

Evidence from artworks show elaborate plaited hairstyles, perhaps something like the way Hera arranged her hair:

Hera covers her elaborate hairstyle with a veil, but for young girls a garland of flowers is often the decoration of choice, as in this description of how the goddesses adorned Pandora:

Athena dressed her and tied her girdle, adorning her.

And the goddesses who are named Kharites [Graces], as well as the Lady Peithō [Persuasion],

placed golden necklaces on its skin, and the Hōrai,

75 with their beautiful hair [kallikomoi], plaited [stephō] springtime garlands [anthoi] around her head.

Pallas Athena placed on her skin every manner of ornament [kosmos].

Hesiod Works & Days 72–76, adapted from Sourcebook

But you, O Dika, wreathe [stephanoō] lovely [eratos] garlands in your hair [phobē, pl.] ,

Weave shoots [orpēx , pl.]of dill [anēthos] together, with slender hands,

For the Graces prefer those who are wearing flowers,

And turn away from those who go uncrowned [asterphanōtos, pl.].Sappho “But you, O Dika,” (fragment 75 quoted by Athenaeus) translated by A.S. Kline, Poetry in Translation

Garlands in the hair can also be envisaged as constellations, as Gregory Nagy describes in the article “About three fair-haired Egyptian queens”:

§2. The part of the story that centers on the constellation itself is retold in many sources, as we can see from the succinct reportage we find in “Eratosthenes” Katasterismoi 27.5 and Hyginus Astronomica 2.5, and the mythological foundations of storytelling about such a constellation known as Ariadne’s Garland are actually most ancient, going all the way back to the Minoan-Mycenaean era.

§3. As before, I focus now not on the garland of Ariadne but on the vertex or ‘head of hair’ adorned by this garland. At verse 62 of the passage I just quoted from Poem 66 of Catullus, we have seen that the vertex of Berenice the Egyptian queen is flavus or ‘blond’. Now I turn to Poem 64 of Catullus: at line 63 here, we see that the vertex of Ariadne the Minoan princess is likewise described as flavus.

§4. So, the hair of Ariadne is blond, as we see it described in Catullus 64.63, while the hair of Berenice is likewise blond, as we saw earlier in Catullus 66.62. And it is this blond hair of Berenice that now joins, as a constellation in the heavens, the garland that once adorned the blond hair of Ariadne.[2]

In the previous post we saw how Athena pulled Achilles’ hair to stop him killing Agamemnon. There are also passages in which women are referred to as being pulled or dragged by their hair, as captives:

(Herald is speaking)

Away with you, away to the ship, as fast as your feet can carry you! If you won’t, your hair shall be torn out [tilmos]; you’ll be pricked with goads, and off will come your heads [840] with abundant letting of gory blood.

Aeschylus Suppliant Women 836–840, adapted from translation by Herbert Weir Smyth(Andromache is speaking)

I saw Hector dragged to death behind a chariot [400] and Troy put piteously to the torch, and I myself went, pulled by the hair [komē], as a slave to the Argive ships. And when I came to Phthia, I was made the bride of Hector’s slayer.

Euripides Andromache 399–404, adapted from translation by David KovacsHelen

[115] And did you capture the Spartan woman?

Teucer

Menelaos caught her by the hair [komē] to drag her away.Euripides Helen 115–116, adapted from translation by E.P. Coleridge /update by Kosmos Society

Free-flowing hair can be associated with independence, or with Artemis. Inappropriately Phaedra imagines herself in this guise:

Phaedra

215 Take me to the mountains—I will go to the woods, 216 to the pine trees, where the beast-killing 217 hounds track their prey, 218 getting closer and closer to the dappled deer. 219 I swear by the gods, I have a passionate desire [erâsthai] to give a hunter’s shout to the hounds, 220 and, with my blond [xanthos] hair [khaitā] and all, to throw 221 a Thessalian javelin, holding the barbed 222 dart in my hand.Euripides Hippolytus, adapted from Sourcebook

Although the texts so often refer to blond hair, the artworks do not always depict it in the same way, as shown in the vase painting of Artemis above. Here is another example from a Mycenaean fresco:

Although having an elaborate hairstyle and decoration or ornamentation is seductive, Gregory Nagy, for example in H24H 3§20, points out that the undoing of the headdress and hair, as in lament, can also be erotic.[3]

We will explore lament and other rituals associated with hair in the next post.

Meanwhile, we invite you to share and discuss further passages and images that provide descriptions of women’s hair and hairstyles. To what extent are they depicting women’s hair as an object of attraction? In what situations do women take control of this process or use it to their advantage? When are women actually dragged by the hair, or is it more often mentioned as a possible threat? What differences are there between younger and older women? What color hair do they have, and does this change over time or is it a matter of convention or of personal preference?

Previously:

part 1 | Male hair: descriptions

Next:

part 3 | Rituals with hair

part 4 | Epithets with hair

Glossary

Terms for hair and descriptions featured in this post (summarized from definitions in LSJ and/or Autenrieth, on Perseus, or from Montanari, Franco The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek.)

anthos ‘blossom, flower’

asterphanōtos ‘uncrowned’

eratos ‘lovely’

khaitā (khaitē) ‘long, flowing hair; mane’

kallikomoi ‘beautiful-haired’

komē ‘hair of the head’

orpēx ‘young shoot’

pekō ‘to comb’

phaeinos ‘bright, radiant, shining’

phobē ‘lock or curl of hair; mane of horse’

plekō ‘to plait, twist; devise, contrive; compound’

plokamos ‘lock or braid of hair’

stephanoō ‘to crown, wreathe’

stephō, ‘to wreathe, crown’

tilmos ‘plucking, pulling out (of hair)’

xanthos, ‘reddish-yellow, blond, auburn (of hair); sorrel or cream-colored (of horses)’

Note: Greek terms incorporated in the quoted passages have been taken from the Greek editions of the texts on Perseus, except:

Alcman Hagesichora, in Trypanis, Constantine A. (ed) 1971 The Penguin Book of Greek Verse, page 131. Harmandsworth.

Sappho 75, on Internet Sacred Text Archive http://www.sacred-texts.com/cla/usappho/sph76.htm

References

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[2] Nagy, Gregory. “About three fair-haired Egyptian queens,” Classical Inquiries 2015.08.19

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/about-three-fair-haired-egyptian-queens

[3] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. (H24H)

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

Image credits

Ring: Woman’s Head, 3rd century BCE, Creative Commons CC0, The Walters Art Museum

Bibi Saint-Pol (photo): Brygos Painter Alkaios and Sappho, Attic red-figure kalathos, circa 470 BCE, Staatliche Antikensammlungen, public domain

Campanian pelike: Greek warrior drags Cassandra from Palladium, circa 330 BCE, Pottery: red-figured hydria: the Sack of Troy; the rape of Kassandra by the lesser Ajax (son of Oileus) at the altar of Athena. 1824,0501.35AN485836001, Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, Attribution: © The Trustees of the British Museum

Jastrow (photo): Artemis pouring a libation, Attic white-ground lekythos, circa 460–450 BCE, Louvre Museum, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Zde (photo): Woman (priestess or goddess) with a bracelet, fresco from Mycenaean acropolis, 13th century BCE, National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

_________________

Hélène Emeriaud, Janet Ozsolak, and Sarah Scott are members of the Kosmos Society.