When one thinks about Greece nowadays, surrounded by sea with crystal clear water, delicious food, and especially sea-food, comes to mind. It is peculiar that, in antiquity, fish was not used in sacrifices. Fish and gods did not get along well.

Fish is not a sacrifice gods fancy. In Aristophanes’ Knights, Aristophanes criticizes Pericles with a grain of humor.

And by Zeus! he carries off bread, meat, and slice of fish [témakhos], which is forbidden. Pericles himself never had this right.

Aristophanes Knights 282–283, adapted from translation by Eugene O’Neill[1]

In The Cuisine of Sacrifice Among the Greeks, Marcel Detienne indicates, on page 3 note 8, that the problem with fish is that it has little blood—and blood is needed for a sacrifice. However, Durand writes in Chapter 4 that tuna, being a big fish with more blood, was used for a special ritual, called “thunnaîon.” Durand, pinpoints “A fish that bleeds is fit to die for the gods” (pages 127–128).[2]

Fish or fishing references appear as similes in ancient Greek texts. The imagery in the Iliad 16, Iliad 23 and Aeschylus, Agamemnon are good examples.

Patroklos went up to him and drove a spear into his right jaw; [405] he thus hooked him by the teeth and the spear pulled him over the rim of his car, as one who sits at the end of some jutting rock and draws a prodigious [hierós] fish [ikhthús] out of the sea [pontos] with a bronze hook and a line [línon]—even so with his spear did he pull Thestor all gaping from his chariot; [410] he then threw him down on his face and he died while falling.

Iliad 16.404–411, adapted from Sourcebook[3]

Clytemnestra describes how she killed her husband, Agamemnon:

[1380] Thus have I done the deed; deny it I will not. Round him, as if to catch a haul of fish [ikthús], I cast an impassable net [amphíblēstron]—fatal wealth of robe—so that he should neither escape nor ward off doom. Twice I struck him, and with two groans [1385] his limbs relaxed.

Aeschylus Agamemnon 1380–1385, adapted from Sourcebook[4]

The scene depicting how Euryalos died is described with a fish simile:

Presently Epeios came on and gave Euryalos a blow on the jaw [690] as he was looking round; Euryalos could not keep his legs; they gave way under him in a moment and he sprang up with a bound, as a fish [ikthús] leaps into the air near some shore that is all bestrewn with sea-wrack, when Boreas furs the top of the waves, and then falls back into deep water.

Iliad 23.689–694, adapted from Sourcebook[5]

Odysseus describes some good king whose land is fertile and the sea around his land yields fish:

107 “My lady,” answered resourceful Odysseus, “who among mortals throughout the limitless stretches of earth 108 would dare to quarrel [neikeîn] against you with words? For truly your glory [kleos] reaches the wide firmament of the sky itself 109 —like the glory of some faultless king [basileus], who, godlike as he is, [110] and ruling over a population that is multitudinous and vigorous, 111 upholds acts of good dikē [= eu-dikiai], while the dark earth produces 112 wheat and barley, the trees are loaded with fruit, 113 the ewes steadily bring forth lambs, and the sea abounds with fish [ikthús], 114 by reason of the good directions he gives, and his people are meritorious [aretân] under his rule.

Odyssey 19.107–115, adapted from Sourcebook[6]

Hesiod describes a harbor with its fish and fisherman in Shield of Herakles. Such a scene, worthy of going on Herakles’ shield might indicate the importance of fish and fishing in Hesiod’s time.

And on the shield was a harbor with a safe haven from the irresistible sea, made of refined tin wrought in a circle, and it seemed to heave with waves. In the middle of it were [210] many dolphins [delphís] rushing this way and that, fishing [ikhthuân]: and they seemed to be swimming [nḗkhesthai]. Two dolphins [delphís] of silver were spouting and devouring [thoinân] the mute fishes [ikthús]. And beneath them fishes [ikthús] of bronze were trembling. And on the shore sat a fisherman [alieús] watching: in his hands he held [215] a casting net [amphíblēstron] for fish [ikthús], and seemed as if about to cast it forth.

Shield of Herakles, 207–215, adapted from translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White[7]

For mortals, fish is a great food source and means to survive. Strabo in Geography says of Elea:

This is the native city of Parmenides and Zeno, the Pythagorean philosophers. It is my opinion that not only through the influence of these men but also in still earlier times the city was well governed; and it was because of this good government that the people not only held their own against the Leucani and the Poseidoniatae, but even returned victorious, although they were inferior to them both in extent of territory and in population. At any rate, they are compelled, on account of the poverty of their soil, to busy themselves mostly with the sea [thalattourgeîn] and to establish factories for the salting of fish [tarikheíai], and other such industries.

Strabo Geography 6.1, adapted from translation by H.L. Jones[8]

Odysseus’ men get desperate for food when their own supplies run out, although they are not impressed with what they can catch:

[325] For a whole month the wind blew steadily from the South, and there was no other wind, but only South and East. As long as wheat and wine held out the men did not touch the cattle when they were hungry; when, however, they had eaten all there was in the ship, [330] they were forced to go further afield, with fish-hooks [ángkistron], hunting fish [ikhthús] and birds, and taking whatever they could lay their hands on; for they were starving.

Odyssey 12.325–332, adapted from Sourcebook[9]

Odysseus’ men might not fancy fish, but Plutarch is onto something. It seems he is giving a recipe for healthy eating:

…of the solid and very nourishing foods, things, for example, like meat and cheese, dried figs and boiled eggs, one may partake if he helps himself cautiously (for it is hard work to decline all the time), but should stick to the thin and light things, such as most of the garden stuff, birds, and such fish [ikhthús] as have not much fat [píōn]. For it is possible by partaking of these things both to gratify the appetites and not oppress the body. Especially to be feared are indigestions arising from meats

Plutarch De tuenda sanitate praecepta, adapted from translation by Frank Coe Babbitt[10]

He also provides evidence that fish could be held in high regard by some, even to the point of excess:

… fish [ikhthús] alone, or above all the rest, is called ὄψον [ópson], because it is more excellent than all others. For we do not call those gluttonous and great eaters who love beef, as Herakles, who after flesh used to eat green figs; nor those that love figs, as Plato; nor lastly, those that are for grapes, as Arcesilaus; but those who frequent the fish-market [ikhthuopōlía], and soonest hear the market-bell. … And what, by the gods, do those men mean who, inviting one another to sumptuous collations, usually say: “To-day we will dine upon the shore [aktázein]?” Is it not that they suppose, what is certainly true, that a dinner [deipnon] upon the shore is of all others most delicious? Not by reason of the waves and stones in that place,—for who upon the sea-coast would be content to feed upon a pulse or a caper?—but because their table is furnished with an abundance of fresh fish [ikhthús]. Add to this, that sea-food [thaláttion ópson] is dearer than any other.

Plutarch Quaestiones Convivales 4.4.2, adapted from the translation by William W. Goodwin[11]

Selected vocabulary

Definitions summarized from LSJ[12]

aktázω [ἀκτάζω] “banquet on the shore, enjoy oneself”

alieús [ἁλιεύς] “one who has to do with the sea, fisherman”

amphíblēstron [ἀμφίβληστρον] “casting-net”

ángkistron [ἄγκιστρον] “fish-hook”

delphís [δελφίς] “dolphin”

ikhthuân [ιχθυᾶν] “to fish, angle”

ikhthuóeis [ἰχθυόεις] “full of fish, fishy,” epithet of the sea

ikhthuopōlía [ἰχθυοπωλία]

ikthús [ἰχθύς] “a fish”

nḗkhesthai [νήχεσθαι] “to swim”

ópson [ὄψον] “relish, sauce; fish, ‘the chief dainty of the Athenians'”

porphureutikós [πορφυρευτικός] “of or for a purple-fisher or dyer”

tarikheía [ταριχεία] “preserving, pickling; pl. factories for salting fish”

témakhos [τέμαχος] “slice-of salt-fish” (later, of meat)

thaláttion [θαλάττιον] “of the sea”

thalattourgeîn [θαλαττουργεῖν] “to be busy with the sea”

thoinân [θοινᾶν] “to feast on, devour”

thunnaîos [θυνναῖος] “an offering of the first tunny-fish caught”

trūgṓn [τρῡγών] “sting-ray”

Notes

[1] Aristophanes, Knights, translated by Eugene O’Neill.

Online at Perseus

Greek text: Aristophanes Comoediae, ed. F.W. Hall and W.M. Geldart, vol. 1. F.W. Hall and W.M. Geldart. Oxford. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1907.

Online at Perseus

[2] Detienne, Marcel and Vernant, Jean-Pierre. 1989. The Cuisine of Sacrifice Among the Greeks. University of Chicago Press.

Detienne, Marcel. “Chapter 1: “Culinary Practices and the Spirit of Sacrifice”

Durand, Jean Louis. “Chapter 4: Ritual as Instrumentality”, in Detienne, Marcel and Vernant, Jean-Pierre. 1989. The Cuisine of Sacrifice Among the Greeks. University of Chicago Press.

[3] Homeric Iliad. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

[4] Aeschylus, Agamemnon. Translated by Herbert Weir Smyth, Revised by Gregory Crane and Graeme Bird. Further Revised by Gregory Nagy.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Aeschylus. Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. 2.Agamemnon. Cambridge. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1926.

Online at Perseus

[5] Homeric Iliad. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

[6] Homeric Odyssey. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919.

Online at Perseus

[7] English and Greek texts: Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Shield of Heracles. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

[8] Strabo. ed. H. L. Jones, The Geography of Strabo. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924.

Online at Perseus

Greek text: Strabo. ed. A. Meineke, Geographica. Leipzig: Teubner. 1877.

Online at Perseus

[9] Homeric Odyssey. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek text: Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919.

Online at Perseus

[10] Plutarch. Moralia. with an English Translation by. Frank Cole Babbitt. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1928. 2.

Online at Perseus

Greek text: Plutarch. Moralia. Gregorius N. Bernardakis. Leipzig. Teubner. 1888. 1.

Online at Perseus

[11] Plutarch. Plutarch’s Morals. Translated from the Greek by several hands. Corrected and revised by William W. Goodwin, PH. D. Boston. Little, Brown, and Company. Cambridge. Press of John Wilson and Son. 1874. 3.

Online at Perseus

Greek text: Plutarch. Moralia. Gregorius N. Bernardakis. Leipzig. Teubner. 1892. 4.

Online at Perseus

[12] LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus

Online texts accessed May 2021.

Image credits

Scorpion Fish Painter: Fish Bowl, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

Photo: Saliko, Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported licence, via Wikimedia Commons

Fish Amphora from Cyprus, 600–475 BCE, British Museum

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

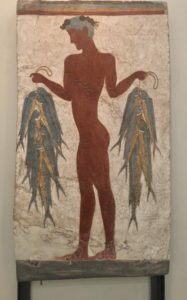

Fisherman fresco, from Thera c1600 BCE.

Photo: Kosmos Society

Fish Vendor: Leagros Group: Attic black-figured olpe, late 6th century BCE. Photo: Egisto Sani. Creative Commons CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 via Flickr

Poseidon with fish 520–510 CE, National Museum of Denmark.

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license via Wikimedia Commons

Online images accessed May 2021.

___

Janet Ozsolak, Hélène Emeriaud, and Sarah Scott are members of Kosmos Society.