When I first heard that the British Museum was putting on an exhibition “Troy: Myth and Reality” I knew I had to go, and I was so happy that friends from the Kosmos Society were able to visit at the same time so we could share the experience with each other. In this post we continue our series of impressions and highlights.

Upon entering the first part of the exhibition space we were taken on a journey through the whole Epic Cycle, as seen through the visual arts of ancient Greece and Rome. I loved seeing items from different periods and from different collections brought together to ‘stitch together’ the narrative. I’d seen some of them before, others only in photographs, and some were new to me; seeing them together in this way brought the story to life visually.

Having seen so many ancient Greek vase paintings it was lovely to see frescos—mainly from the Roman period—which were new to me. Here is one depicting Hephaistos forging the armor for Achilles, including the famous shield.

and another showing the wooden horse being dragged into Troy:

As you proceed through the exhibition, suddenly IT looms ahead, unmissable, towering above people and displays, THE horse, an immense carcass of beautiful amber-coloured wood.

The whole structure is quite ingenious, worthy of Odysseus: evocative of the curved and graceful spine and ribs of a horse, but also, very cleverly, of the inverted hull of a ship, a most appropriate reminder that the Greeks used the same wood for the horse as they had done for their ships. Inside this ribcage-like shell, visitors mill about, looking at more displays, so that one gets the impression of being inside the horse—enclosed as the Achaeans would have been—but of being outside too; we are ready to exit just as the same Achaeans had been ready to jump out. The whole structure is so light and airy, reaching up quite high, almost ethereal.

For me, a most effective minimalist recreation of the famous horse.

Since I’m involved with three translation/discussion groups focusing on the Odyssey I found it especially interesting to see the displays of the Nostoi and Odysseus in particular.

Another fresco shows the Sirens, one of the key moments in the Odyssey. In Circe’s warning she explains:

You will come to the Sirens who enchant [40] all who come near them. If anyone unwarily draws in too close and hears the singing of the Sirens, his wife and children will never welcome him home again, for they sit in a green field and warble him to death with the sweetness of their song. [45] There is a great heap of dead men’s bones lying all around, with the flesh still rotting off them.

Odyssey 12.39–46, Sourcebook

The exibition text[2] for this fresco explained that Odysseus was a popular subject, and points out that two of the Sirens are playing instruments, “while the third is presumably singing.”

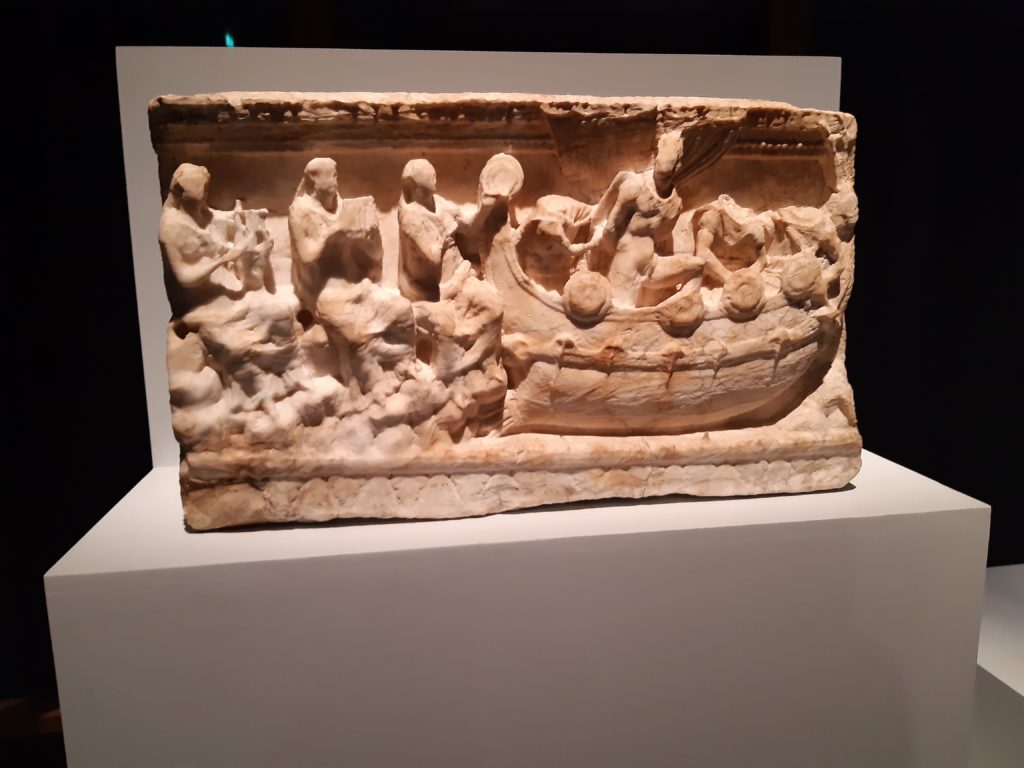

There was also a lovely Etruscan carving of the same episode. The exhibition text noted that “The episode was a popular subject for Etruscan funerary urns, chosen as a metaphor for the final journey of the deceased as they reluctantly leave behind life’s pleasures.” Again, the Sirens are shown with instruments.

Another favorite item here was a marble head of Odysseus; the caption explained that the “conical hat (pilos) is that of a traveller.” The expression on his face struck me as that both of the man of “many wiles” [polumētis] and also of the “much-enduring” [polutlas] man.

A vase that caught my eye depicts Odysseus, holding the moly root, intending to attack Circe for turning his men into pigs, while she intends to drug him. I was intrigued by its comic appearance! The caption explains “The burlesque scenes, unusal in Greek art, may illustrate ritual theatre performances.”

I also found the detail of the loom interesting, and I think this is likely to be more realistic.

There was a fabulous depiction of Scylla, with a wonderful writhing tail, a human and dog heads, and partially eaten men. It brought to mind the Circe’s vivid warning to Odysseus:

Scylla sits and yelps with a voice that you might take to be that of a young hound, but in truth she is a dreadful monster and no one—not even a god—could face her without being terror-struck. She has twelve misshapen feet, and six [90] necks of the most prodigious length; and at the end of each neck she has a frightful head with three rows of teeth in each, all set very close together, so that they would crunch anyone to death in a moment…No ship ever yet got past her without losing some men, for she shoots out all her heads at once, [100] and carries off a man in each mouth.

Odyssey 12.85–92, 99–100, Sourcebook[1]

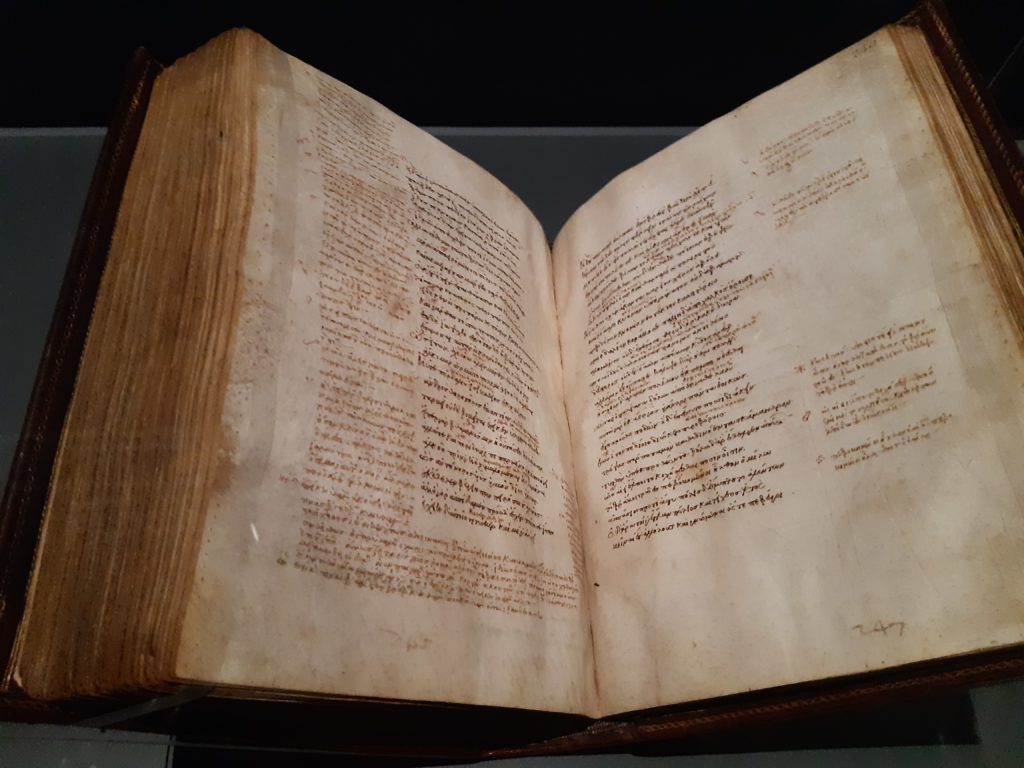

The latter part of the exhibition focused on transmission, later interpretations, and the excavations at Troy by Schliemann and others. In this section, I was drawn to a manuscript of the Iliad, with many scholia annotations. I love the little symbols and signs the scribe has used for the marginal notes (most visible on the right-hand page). Although the writing takes some getting used to, I’ve been looking at the photograph in detail to see if I can work out which passage is displayed on these pages. I think it is from Iliad 21.556–609 where Hector is debating with himself whether to remain and fight, Achilles makes a fruitless attempt on Agenor and is lured by Achilles toward the river Skamander, and the right-hand page ends with the Trojans fleeing back into the city.

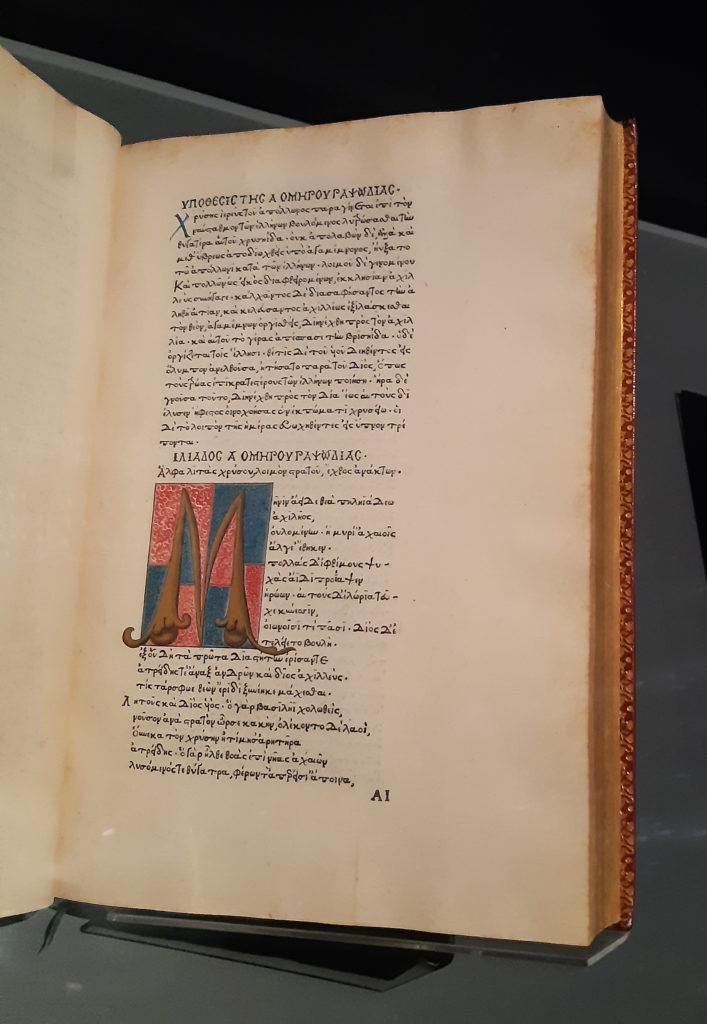

The first printed Greek edition was beautiful. This one is easier to read: the text starts around halfway down the page with the opening lines of the Iliad. You can see the large illuminated capital letter ‘M’ for Μῆνις [Mēnis].

Next: Part 3: Thoughts on the book and exhibition

Notes

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2019.12.12. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

[2] From the exhibition text. The Trustees of the British Museum.

Online sources accessed March 2020.

Image credits

Photos: Kosmos Society. Image captions based on attributions at the exhibition.

_____

Claudie Cox and Sarah Scott are members of the Kosmos Society.