Meeting with several members of the Kosmos Society in London in February was a wonderful experience. We went together to the amazing exhibition “Troy: Myth and Reality” at the British Museum. The British Museum was packed with fans of Homeric poetry, so we were among people sharing similar enthusiasm. Now we offer some of our highlights.

The Troy Exhibition at the British Museum captures you from the moment you enter; there is darkness accompanied with ominous music which cuts your ties from the vast halls of the museum and takes you to Troy!

“The Judgement of Paris” is one of the early pieces in the curvy setting of the exhibition. This is an Etruscan wall painting dated about 560–550 BCE, found in Cerveteri , Italy. The explanation that is given by the museum is as follows:

On the left, Trojan prince Paris is approached by Hermes, the gods’ messenger, followed by Athena, Hera and Aphrodite. Zeus has decided that Paris must judge which goddess is most beautiful. Aphrodite, is lifting her dress to show off her boots and a flash of leg, will win. She has promised Paris the hand of Helen, on the right adjusting her snake-like girdle. Three women approach Helen with wedding gifts. But she looks away, perhaps unhappy to be offered as a prize.[1]

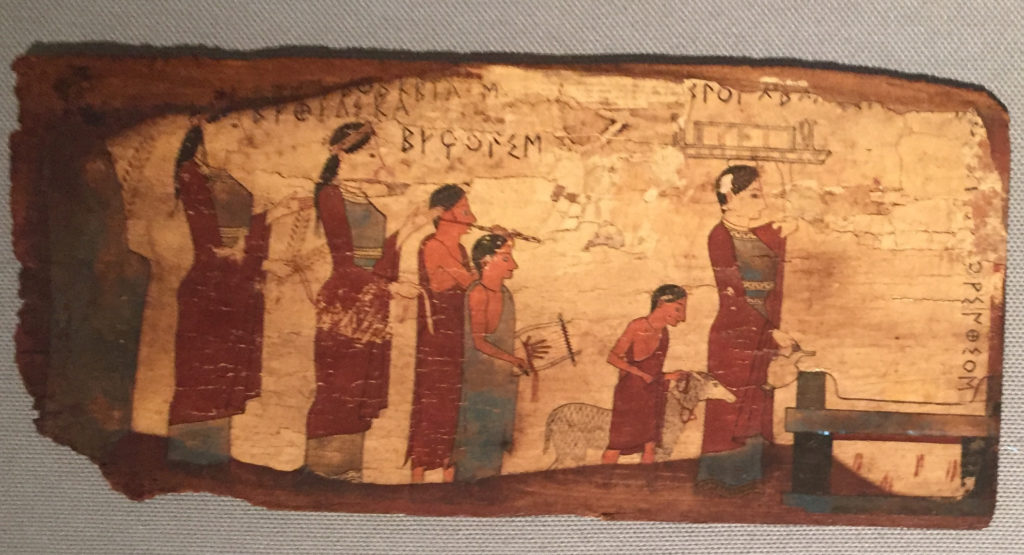

This painting reminded me of a plaque I saw in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

This is one of the four wooden plaques discovered in a cave, near ancient Sikyon, above the village of Pitsa in Corinthia in 1934. This is a procession to offer a sacrifice. You can see the lamb, lyre and flute, along with the possibly undiluted wine libation.

The similarity of the colors and the composition made me wonder if these two locations are related to one another. A quick internet search revealed that the modern city Cerveteri was known as Agylla by the ancient Greeks, had close trade relationships with the southern Greek settlements in Italy and further parts of ancient Greece. So close was the relationship that the Etruscan Cerveteri was the only Etruscan city to have a treasury, the Treasury of Agylla, at the sacred city of Delphi.[2]

On an amusing note, the figures representing Paris and Hermes on the wall painting at the exhibition reminded me of Karagöz and Hacivad also known as Karagiozis.

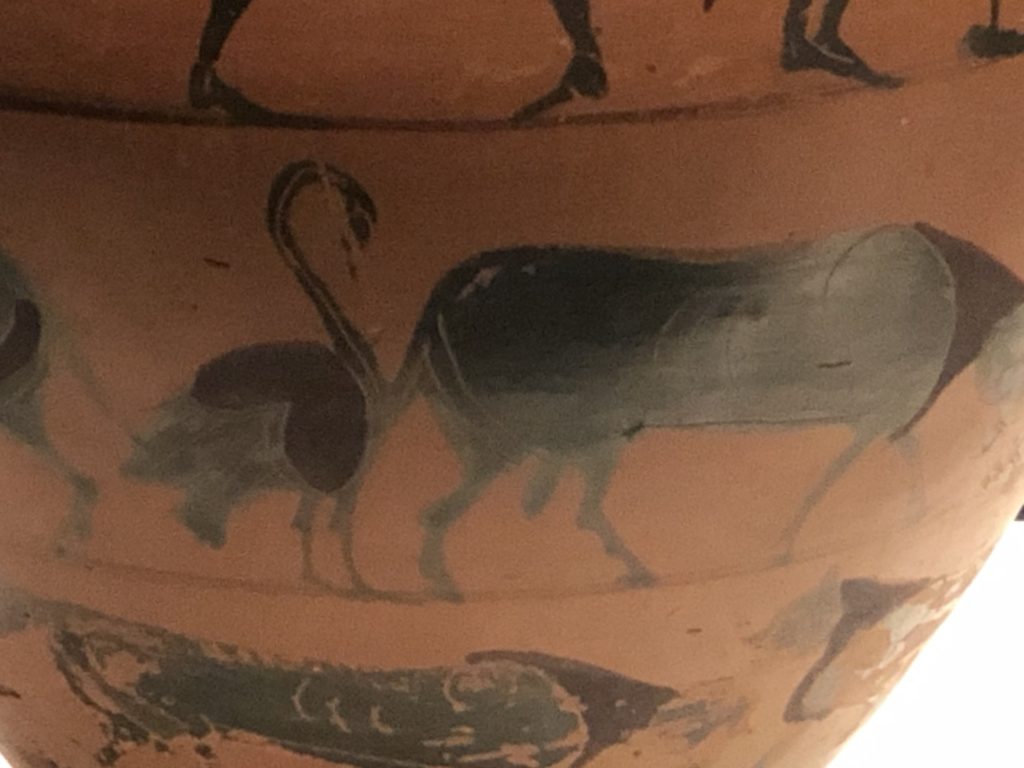

The depiction of a bull and an egret also captured my attention. Here are two images: the first is from the Greek gallery of the British Museum.

And this one is from the Troy Exhibition.

The bull is an animal we hear about in sacrifices in the epic, but I got curious about the egret. The egret, which is also known as heron, is a bird the gods use as messengers or signs. In Iliad 10, Athena sends a heron for Odysseus and Diomedes on their night raid:

When the pair had armed, they set out, and left the other chieftains behind them. Pallas Athena [275] sent them a heron by the wayside upon their right hands; they could not see it for the darkness, but they heard its cry.

Iliad 10.273–277, Sourcebook[3]

_______

Meeting with several members of the Kosmos Society at the British Museum for the superb exhibition was a wonderful experience.

I tried to take as many pictures as I could but the place was dark, therefore the quality of the pictures is mediocre.

One painting caught my attention: Helen is represented with Agamemnon’s daughter, Iphigenia, an unusual pair of women is painted on this watercolor.

It strongly suggests that Helen was responsible and feels guilty for the death of Iphigenia.

The card at the exhibition notes:

Unusually, this painting shows Helen with Iphigenia, Agamemnon’s daughter sacrificed to enable the expedition to Troy. It is based on Alfred Tennyson’s poem ‘A Dream of Fair Women’ (1833), in which Helen expresses deep regret to Iphigenia, who is immovable:But she, with sick and scornful looks averse,

To her full height her stately stature draws;

‘My youth,’ she said, ‘was blasted with a curse;

This woman was the cause…’

Tennyson’s poem pinpoints Helen’s responsibility, and the painting is painfully stunning.

However, several reliefs in the exhibition offer different views about Helen and Paris‘ elopement, and about Helen’s responsibility. Here, one shows Helen being abducted, while another one shows that the gods are responsible.

In the one below, Paris and Helen meet with help from the gods:

Here is the text from the card at the British Museum exhibition:

Paris, prince of Troy, travels to Sparta on a state visit. He leaves with his host Menelaus’ wife, Helen. This scene clearly blames the gods for their relationship. Eros, the personification of love as a winged boy, plants desire in Paris. A modest-looking Helen is being coaxed by Aphrodite, who sits beside her. Peitho, the goddess of persuasion, presides over the meeting from the top of a column.

On this relief above, clearly the gods are behind the elopement. However, on a funerary urn Helen is abducted by Paris.

The information card explains:

Etruscan funerary urns sometimes show a reluctant Helen, as if her love-affair with Paris was a cold-hearted abduction. Here a bored-looking Paris sits by his ship while his men push Helen on board, just another treasure that he is taking from Menelaus’ palace. On funerary urns the unwilling Helen may stand for the dead person reluctantly parting from life.

This interpretation clearly shows an abduction.

The last picture of a beautiful but faded fresco from Pompeii shows a hesitant Helen leaving for Troy.

As Helen leaves for Troy, the exhibition text tells us:

A servant helps Helen onto the ship that will take her to Troy, steadying her as she steps hesitantly onto the gangplank. Helen seems to leave her husband willingly, but with a sense of foreboding.

The question is still open, was Helen abducted or did she go willingly?

We do not really get a definite answer from the beautiful artifacts at the British Museum about Helen’s responsibility. The same ambiguity appears also in ancient Greek literature. Euripides, in his play Helen, portrays Helen as a victim: she never went to Troy, only her phantom did. She remained faithful to Menelaos, and is gladly reunited with him at the end of the play.

However in another drama, the Trojan Women, the same Euripides shows Helen as being guilty and blamed as the cause of all the sufferings.

Even Helen herself realizes that the story of the war of Troy will be the subject of endless stories, as she says in Iliad 6 to Hector:

Still, brother, come in and rest upon this seat, [355] for it is you who bear the brunt of that toil [ponos] that has been caused by my hateful self and by the derangement [atē] of Alexandros—whom Zeus has doomed 357 so that even in the future 358 we will be subjects of song for men yet to be.

Iliad 6.354–358, Sourcebook

The story was told and pictured endlessly in the past and will continue to be in the future.

Next: Part 2: Frescos, the Horse, Odysseus, and written transmission

Notes

[1] From the exhibition text. The Trustees of the British Museum.

[2] https://www.ancient.eu/Cerveteri/

[3] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2019.12.12. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

Online sources accessed March 2020.

Image credits

Karagöz and Hacivad: Kıvanç (photo), Karagoz (shadow play). Istanbul Toy Museum.

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license via Wikimedia Commons.

All other photos: Kosmos Society. Image captions based on attributions at the exhibition, or at other museums noted.

____

Hélène Emeriaud and Janet M. Ozsolak are members of Kosmos Society.