When one visits the famous ancient sites of Greece, one soon realizes that most of these were built at places sacred to one or more of the ancient Greek gods—Zeus, Hera, Apollo, Athena and Poseidon among them. It seems the gods were a real presence to the ancient Greeks, influencing how they lived their everyday lives, their political decisions, and their world view. They seem to have believed they could honor or interact with the gods most effectively at select locations, places chosen by the gods or by human events where mortals could communicate with the immortals.

A tour of ancient Greek sites—organized as a collaboration between CHS Greece and the Harvard Alumni Association, and led by Professor Gregory Nagy—had been originally planned for 2020, postponed and then postponed again in 2021, and was finally organized for March 2022. Our initial base was the port city of Nafplion, and the first site we visited was the Heraion, the Sanctuary of the goddess Hera, located in the hills overlooking the plain of Argos, known as the Argolid, in the Peloponnesus.

It is said that March comes in like a lion, and out like a lamb. However, in Greece during March of 2022, the weather came in like a lamb, continued like a tiger, and then only moderated to the occasional lamb-like condition, before roaring back with leonine ferocity. In other words, it was cold and rainy. One, or the sole, benefit of the cold weather was the snow covering most of the mountains. As we travelled across the Peloponnesus and later central Greece, the snow framed the mountains and made it apparent, as is often stated, that Greece is a county of flat, fertile alluvial plains and stark rocky mountains.

Argos

In the photo above taken from the Sanctuary of Hera, the acropolis of the great ancient city of Argos stands out across the plain. The Bronze age citadel of Mycenae is among the hills to the right of the Sanctuary, and the plain was contested by the two cities in Archaic and Classical times until the city of Argos assimilated the classical city of Mycenae and claimed the entire plain. One can consider much of ancient Greek history as consisting of conflicts between cities, known as city-states (poleis plural, polis singular) over the flat fertile plains between them.

It is clear from the prominent location of the Heraion that the goddess Hera was important to the ancient inhabitants of the Argolid. At our visit, Professor Nagy focused on the legend of Kleobis and Biton, and the connection between the ancient literary references to these heroes at the Temple of Hera and the discovery of their statues in modern times. The heroes were two brothers from Argos whose mother was a priestess at the temple of Hera. When the oxen to pull their mother’s cart for an important festival were missing, the brothers yoked themselves to the cart and pulled their mother ten kilometers to the temple. Arriving, their mother prayed for Hera to bestow a gift on her sons for their devotion, and Hera rewarded the priestess by giving the young men eternal sleep: allowing them to die at the height of their strength after performing a great deed. The villagers honored the men with statues presented to the temple of Apollo in Delphi. This story is featured in Herodotus’ Histories, written in the mid-fifth century BCE. Pausanias, writing in the second century CE, viewed the statues at Delphi. These statues were discovered in one of the earliest modern archeological digs in Greece, a testament to the existence of the legend and the brothers’ veneration as reported by the two ancient historians.

The group then moved to the Bronze Age citadel of Mycenae itself, historically the site of the leading city of the Mycenean civilization, which lasted from about 1750 to 1050 BCE, and the fabled home to king Agamemnon. Homer’s Iliad has Agamemnon leading the Greeks to Troy in the Trojan war, and the great epic is centered on his feud with the hero Achilles, and the terrible destruction visited on the Greeks because of their quarrel. Although we did not view a location in Mycenae specifically linked to a god or goddess, one can infer that the Mycenaeans believed in much the same gods as the Greeks of the Archaic and Classical period. The far ancestors of the Greeks, the Proto Indo-Europeans, believed in Dyews Phter, the daylight sky god, and his consort Degom, the earth mother (according to Wikipedia). Greek mythology featured a sky god, Ouranos, and an earth mother, Demeter, although these were superseded by Zeus and Hera at the top of the pantheon. The Iliad and Odyssey, which were probably composed or consolidated out of extant myths in the eighth or seventh centuries—only a few hundred years after the end of the Bronze Age—include the main Olympian gods.

The museum at Mycenae is filled with interesting artifacts. These include a partial fresco reminiscent of the lovely frescos at Knossos in Crete and Akrotiri on Santorini, and the strange terracotta statues of gods or priests pictured below:

That evening we were given a tour of the lovely town of Nafplion, including an old plane tree in the center of town (from the Greek ‘platus’ meaning broad, in reference to the wide leaves). Professor Nagy praised the aria ‘Ombra mai fu’ (‘Never was a shade…’) from Handel’s opera Xerxes where King Xerxes sings to his favorite plane tree. FYI, the aria is wonderful, but from the description, the opera appears to be a melodrama which has virtually nothing to do with the event for which Xerxes is best remembered: the Persian War of 480 BCE when his fleet and army invaded Greece and were defeated at the naval battle of Salamis and the land battle of Platea (the name of the town was evidently derived from the same word—“broad or wide”—, which coincidentally was the basis for the nickname of the most famous Greek philosopher, Aristocles, son of Ariston, known as “Plato” for his broad forehead.)

Olympia

The next day the group was off to the Sanctuary of Olympia, sacred to Zeus, ‘Thunderer’, the most powerful of the Olympian gods. Olympia is located on the fertile plain of ancient Elis, which along with other fertile lands was itself subject to repeated conflicts. As is reported by ancient writers, the Olympic games were said to have begun in 776 BCE, and evolved to become the foremost athletic and religious festival in classical Greece. Athletes and spectators from all over the Greek world converged at the site every four years during a period of truce, in which no travelers to the Olympics could be harmed, and all wars were to cease.

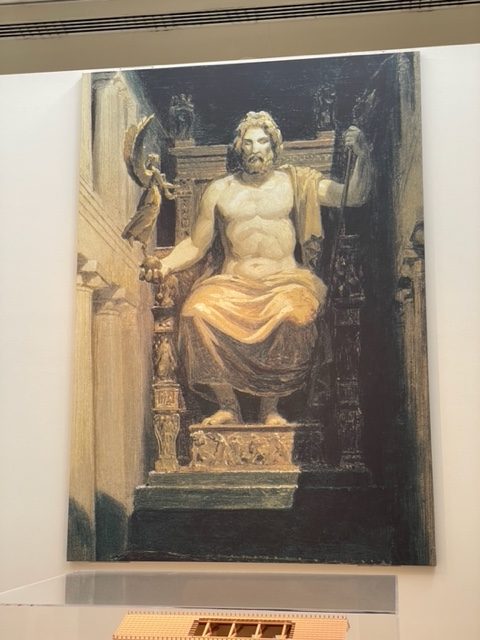

The group viewed the site, including the Temple of Zeus, which in ancient times housed the giant gold and ivory statue of the god—sculpted by the famed artist Pheidias—which was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World by Antipater of Sidon.

We also visited the original Olympic stadium, which coincidentally, is one Stade long—about 606.9 feet or about an eighth of a mile (c 185 meters.) The remains of the entrance tunnel exist, from which the athletes entered the stadium. Some of the more energetic participants ran the length of the stadium, while others contemplated the fact that in ancient times thousands viewed the athletic contests, and the winners were celebrated by their cities, and often given gifts, including meals for life (evidently a big thing in the ancient world).

The museum at Olympia was filled with treasures, including the Hermes by Praxiteles, and the remains of the Apollo from the temple pediment.

Delphi

Delphi is in quite an inaccessible site. In contrast to the plains of Argos and Elis, it is placed high on a gorge by Mount Parnassus. Rather than providing a bread-basket for a large population, Delphi provided the ancient Greeks with prophecies for the future! Ancient Greeks would travel by foot or horse for days over rough mountain trails to reach the famous site.

Delphi was sacred to Apollo, the god of truth and prophecy, healing and disease, music and dance, and archery. The Sanctuary of Delphi was renowned for its oracle, the Pythia, who—influenced by vapors from the earth—was one of the premiere soothsayers in the ancient world. According to legend and history, the Oracle at Delphi was interpreted incorrectly by the king of Lydia, Croesus, to attack the Persian empire, and correctly by Themistocles of Athens to abandon the city to the Persians and confront them within the “wooden walls” of its fleet.

Upon arrival, travelers would have taken a winding path past the “treasuries” of the various cities—in which were kept the offerings made to Apollo over the centuries—up to the Temple of Apollo. Below is the site with the remains of the Temple of Apollo visible, and the reconstructed Treasury of the Athenians.

As pointed out by Professor Nagy, the Pythia would sit in the center of the temple, shown below, and inhale the vapors seeping out from a crack in the earth. The Pythia, in this vapor-induced trance, would call out unintelligible words, which would be interpreted by a priest of Apollo as a Dactylic Hexameter poem. The recipients would have then interpreted the cryptic oracle as best they could—with the obvious pitfall of potential misinterpretation à la Croesus.

Delphi was the center of the Greek world, and administered by a league of twelve founding populations. A stone there, the Omphalos, was considered the “navel of the earth.” In Archaic and Classical times the administration (and tribute) of Delphi was fought over in the Amphitryonic Wars. Every four years, Delphi hosted the Pythian Games, the second most important (after Olympia) of the Greek religious/athletic festivals.

The museum at Delphi contains a number of wonderful treasures. Foremost were the statues of Kleobis and Biton, about whom we first heard at the Heraion in the Argolid. According to the museum, the statues were produced in Argos between 610 and 580 BCE. The stone Omphalos has also been preserved.

Also of prime note is the famous Charioteer, a bronze statue from the 5th century, produced in the “austere” style. A statue of Agias of Pharsalos is a possible production of the famous sculptor Lysippos.

Athens

Athens was sacred to the goddess Athena, associated with wisdom, handicraft and warfare. The ancient Athenians worshipped the goddess in many forms. There was Athena Polias, goddess of the city; Athena Parthenos, the unmarried or virgin; and Athena Promakhos, the warrior goddess.

Athens’ countryside, known as Attica, was not one of the supremely fertile plains such as Argos, Sparta’s land of Laconia, Boeotia, Messenia, or Elis. Rather, in Classical times it was known for the production of olives, olive oil and wine, which grow well in its rocky fields and hills. But primarily, Athens was known for trade and its navy. Its trading fleets reached across the Aegean, Ionian, and Black Seas and it became the foremost naval power in the Eastern Mediterranean from 480 to at least 330 BCE.

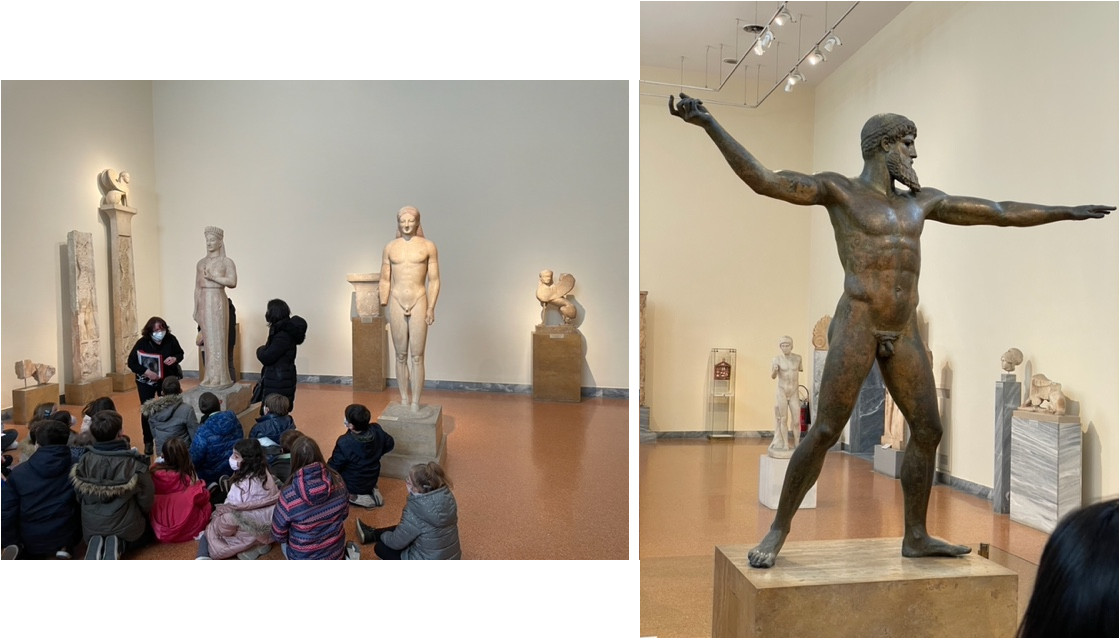

Our itinerary took us across Athens: to the Acropolis to see the famed Parthenon temple; to the ancient Agora, where the Athenians meet to trade and talk; and to the great museums, the Parthenon museum, the Agora museum, and the National Archeological Museum. The weather alternated cold and rain with some sun. We attempted to pacify the gods with wine, but without much success. Some of the highlights were:

-

The Agora or ancient central marketplace of Athens, including the Poros—the state prison where Socrates is said to have been housed:

-

The Acropolis Museum, where we saw the famous Caryatids from the Erechtheum, and the Parthenon frieze—including this panel of the horsemen riding in the Great Panathenaea procession:

-

The Parthenon itself and the Acropolis Propylaea (gateway):

-

The lovely Phrasikleia Kore from about 550 BCE—with some of its colorful paint remaining—and the adjoining Kouros of a young man; and the famous bronze of either Poseidon or Zeus:

-

The cats of Athens:

Cape Sounion

So far, our journey had taken us to locations associated with the gods Hera, Zeus, Apollo, and Athena. I made a final trip down the coast of Attica to the Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion, from where ancient Athenian ships rounding the cape could see the sunshine sparkle from the tip of the spear of the statue of Athena Promakhos on the Acropolis sixty kilometers away, and know they were near home. Poseidon was the god of the sea and earthquakes, so must have protected this temple through its long history:

The ancient gods had been honored, the awe-struck visitors making the pilgrimage to each of their shrines. Fertile valleys and snow-capped mountains had been crossed. Many libations of lovely wine had been spilled (by accident), and hecatombs of souvlaki roasted in the gods’ honor, the smoke sent heavenward.

Now it was time to return to normal pursuits, and the time-honored sites of ancient Greece left behind—for now…

_______

Information about the sites is based on that supplied during the tour.

All photographs by the author.

Ian Joseph is a member of the Kosmos Society.