The Punic wars were a series of conflicts encompassing 43 years of war over more than a century, from 265 BCE to 146 BCE. They led to the Roman Republic controlling much of the Mediterranean world, to the ruin of a great North African civilization, and to many modern people speaking a Latin-based or Latin-influenced language. They occurred about 120 years before the Empire was established under Augustus Caesar in 27 BCE.

Our main source for information about the Punic Wars is the historian Polybius, a Greek sent to Rome in 167 BCE as a hostage. He became a friend and mentor of the Roman general Scipio Aemilianus, nephew of Scipio Africanus. This is important because most Carthaginian writings were destroyed when Carthage was burned in 146 BCE.[1] We also have accounts from later authors such as Livy (circa 25 BCE) and Appian of Alexandria (circa 165 CE).[2]]

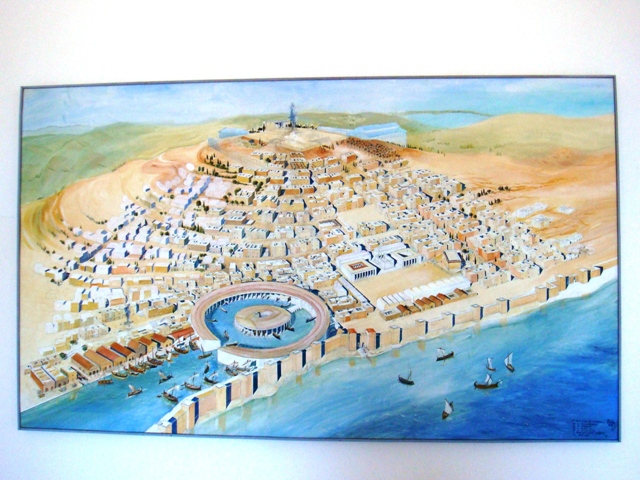

According to Vergil’s Aeneid, Carthage was founded by Dido, a refugee princess from Tyre.[3] Whether this was true or not, Carthage was indeed a settlement of Phoenician traders, probably from the region that today is part of Lebanon.[4] The city of Carthage, located in what is today Tunisia, became an important port and trading center, with settlements in North Africa, Spain, and Sicily.[5] The Punic Wars are called the Punic Wars because the ancient Greeks called the Phoenicians Φοίνικες (singular: Φοῖνιξ). The Romans adapted this term, using “poenus” and “punicus” to refer to the Carthaginians.[6]

Rome arose on the Tiber River about 753 BCE. According to legend, it was founded by descendants of the Trojan prince Aeneas, Romulus and Remus.[7] Whatever its origins, it grew from a small settlement of huts to an enormous empire. Rome’s holdings eventually completely spread around the Mediterranean and even reached the British Isles.[8]

At the time of the Punic Wars, neither Rome nor Carthage was a monarchy. Rather, Carthage was governed by a counsel made up of 300 wealthy citizens and two annually elected leaders called suffetes.[9] Similarly, Rome was under the control of the Senate and two annually elected consuls.[10]

Whether the First Punic War, lasting from 264 to 241 BCE, was sparked by the actions of pirates or the more polite term mercenaries is a debate among scholars, but all agree that these rough and ready fellows were Italian.[11] Calling themselves “men of Mars,” or “Mammertines,” they decided to invade the Sicilian town of Messana, originally a Greek colony. After doing so, they really turned into pirates, looting and pillaging many centuries before the Vikings ever left Scandinavia.[12] Thus began a 23-year conflict.

Heiro, the ruler of another Sicilian Greek city, Syracuse, took exception to the looting and pillaging, and besieged Messana. Needing assistance, some of the Mammertines appealed to the Carthaginians, who had a significant presence in Sicily.[13] The Carthaginians helpfully sent troops from their fleet anchored nearby and took back the city of Messana.[14] However, some others of the Mammertines apparently did not want to live under Carthaginian rule, so they appealed to Rome, possibly on the basis that, as Samnites, the Mammertines were fellow Italians.[15]

While the Roman Senate was initially cautious about invading Sicily, eventually the threat of the Carthaginians controlling a city so close to the Italian mainland convinced Rome to send a fleet to Messana.[16] In the meantime, the Mammertines had forced the Carthaginians out of Messana, but were then besieged by both the Carthaginians and the Syracusans.[17] The Roman commander, Caius Claudius, invaded Sicily, setting out from the port of Rhegium on the southern coast of Italy. He attacked first the Syracusans and then the Carthaginians. After Claudius took control of Messana and besieged the city of Syracuse, Syracusan ruler Heiro made peace with the Romans and remained an ally.[18]

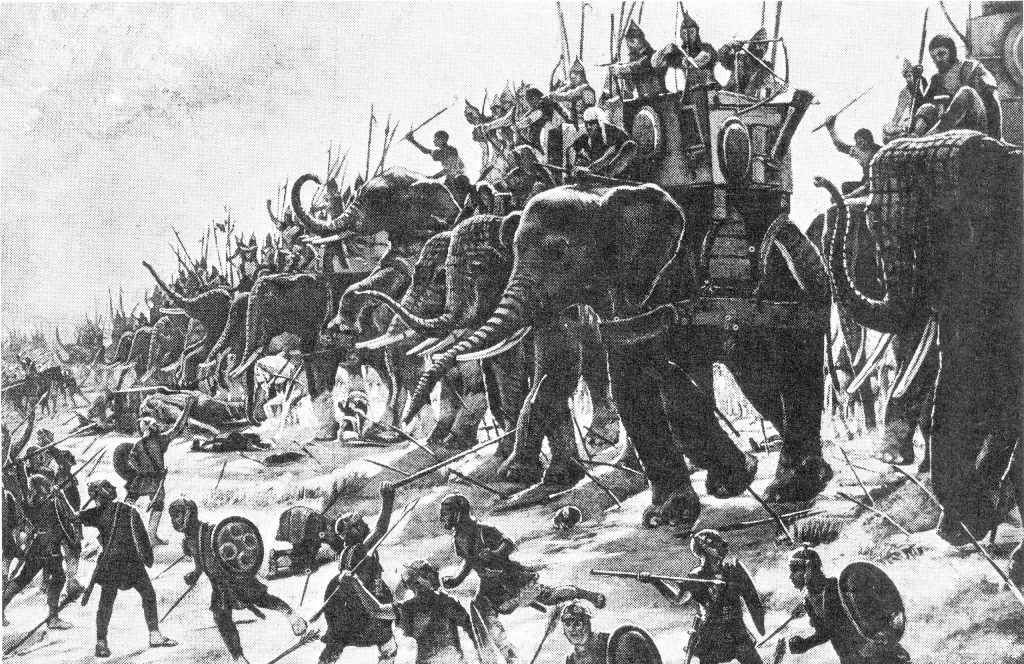

Following their success at Syracuse the Romans sent more troops—four legions plus allies, who marched to Agrigentum on the southwest coast of Sicily. This city was occupied at the time by the Carthaginian general Hannibal Gisco and his garrison.[19] After the two sides besieged each other, reinforcements, including 50 war elephants, arrived from Carthage, commanded by the general Hanno. Eventually, after more periods of siege, the Romans defeated the Carthaginians, and by about 261 BCE, Rome controlled most of Sicily.[20]

At the start of the war, the Romans had a strong land army, and had made many conquests in Italy. However, they were not great sailors.[21] The Carthaginians, on the other hand, had the best navy in the Mediterranean world.[22] According to Polybius, the Romans had a stroke of luck when a Carthaginian warship washed up on the shore of Italy in about 260 BCE. Using this ship as a model, the Romans quickly constructed a fleet of 20 triremes and 100 quinqueremes. Polybius goes on to state that Roman oarsmen trained on benches on shore while the ships were under construction.[23]

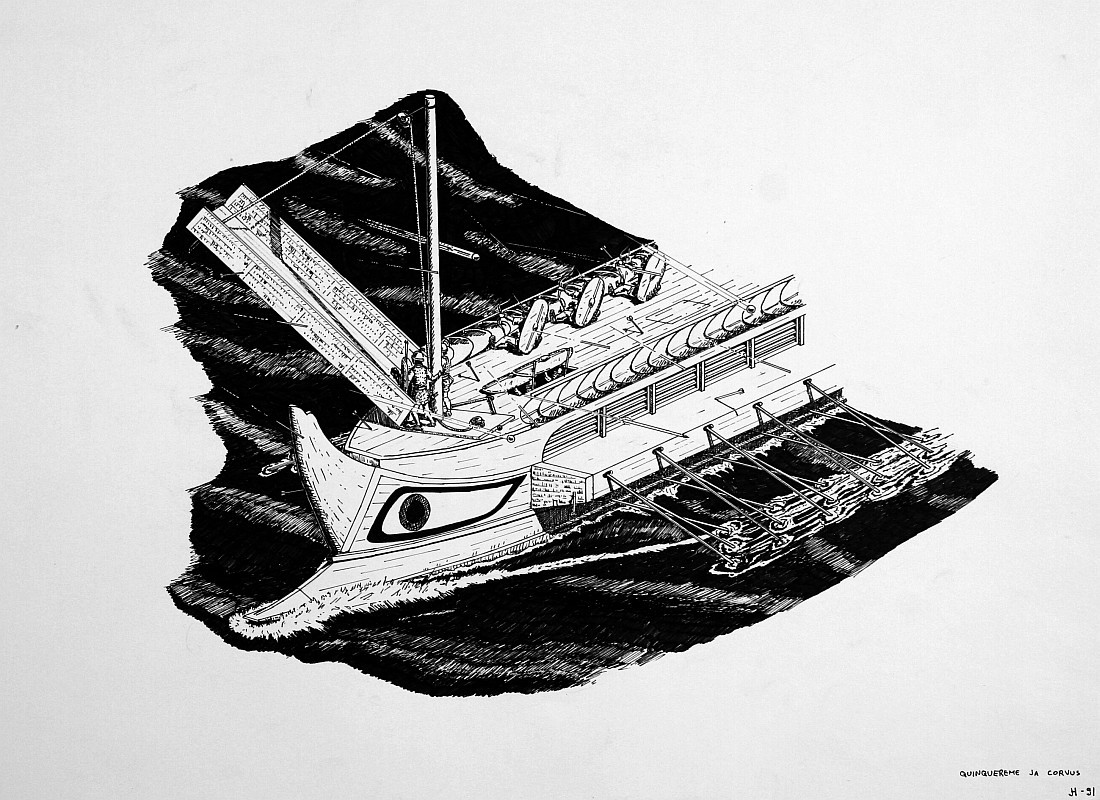

Historian Adrian Goldsworthy describes triremes as having three levels of oars, with the upper level projecting from an outrigger. Each level was manned with one rower. A quinquereme had five rowers, but it is not certain how they were arranged. Goldsworthy points out that it would have been unlikely that a quinquereme referred to five levels of oars, since such an arrangement would prove too difficult to coordinate and maneuver, but referred to five oarsmen on each oar.[24]

However their warships were configured, the Romans also figured out how to take their land warfare skills to the sea. They developed a machine called a corvus, which means raven or crow. This was a large iron spike attached to a platform which in turn was attached by a hinge to the deck of Roman ships.[25] Roman ships approaching enemies lowered the spike, trapping the opposing ship. The platform created a bridge and marines boarded the enemy ship and engaged in close quarters combat. However the corvus was unwieldy, causing ships to list in the water, possibly leading to its use being abandoned after the First Punic War.[26]

With their new fleet the Romans defeated the Carthaginians at sea in the battle of Mylae (modern Milazzo on the east coast of city Sicily) in 260 BCE.[27] In 256 BCE, the Romans set course for the coast of North Africa, intending to invade the Carthaginian homeland.[28] They were intercepted by the Carthaginian fleet at the Cape of Ecnomus (near modern Licata on the southern coast of Sicily).[29]

The battle of Ecnomus may be the largest naval battle of all time in terms of numbers of combatants. It is estimated that the Roman fleet had 140,000 men including marines and crew, and that the Carthaginians numbered 150,000 men.[30] The Roman fleet was commanded by co-consuls Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manilius Vulso. The Carthaginian fleet was commanded by Hanno and Hamilcar (a different Hamilcar from Hamilcar Barca, the father of Hannibal, the famous general of the Second Punic War).[31]

In the battle the Romans used a four-squadron formation to increase maneuverability. Three squadrons formed a triangle and the fourth squadron formed a line at the back. The Carthaginians used a single line of ships with one squadron, Hanno’s, angled toward the coast.[32] The Carthaginians found it difficult to defend against the Roman use of the corvus.[33] In addition, the Carthaginians were less skilled in individual combat than the Romans, and so could be overwhelmed when the corvus allowed the marines to board their ships.[34] The battle lasted an entire day, and the Carthaginians were eventually defeated, losing 30 ships to sinking and 64 ships to capture. The Romans lost only 24 ships.[35]

Afterwards the consul Marcus Regulus landed with four legions in what is today Tunisia. Strangely, the Roman Senate chose this moment to recall half of the army and the whole fleet.[36] However even with reduced numbers the Romans were able to win some decisive engagements, possibly due to the rough terrain which made use of elephants impossible.[37] The opponents started peace talks, but they broke down because of the harshness of the Romans’ demands.[38]

After the peace talks faltered, Rome suffered a defeat in 255 BCE in the Battle of Bagradas River near Carthage, at the hands of a mercenary commander from Sparta named Xanthippus. The Romans lost 12,000 men as opposed to only 800 losses for the Carthaginians.[39] The rest of the Roman army managed to flee. A fleet was dispatched to pick them up, but a storm destroyed the ships, drowning as many as 100,000 men. According to Polybius, this was the greatest naval disaster in history.[40] More Roman losses due to storms occurred in 253 BCE when the fleet of 150 ships under the command of C. Sempronius Blaesus was sunk after a raid on North Africa, and in 249 BCE, when 800 Roman supply ships were sunk off the Bay of Gela in southern Sicily.[41]

Also in 249 BCE, Rome suffered a defeat at the Battle of Drepana (modern Trapani on the west coast of Sicily). Before the battle, the Roman consul, Publius Claudius Pulcher, was said to have thrown the sacred chickens overboard when the chickens refused to eat, thus giving a bad omen for the upcoming engagement.[42] According to Cicero and Suetonius, Pulcher is supposed to have declared: “ut biberent, quoniam esse nollent?”(since they will not eat, let them drink).[43] While it is not possible to blame the outcome entirely on the unlucky birds, the result of the Battle of Drepana was 93 Roman ships captured, 20,000 Romans killed or captured, and an unknown number of Roman ships sunk, giving Carthage its most significant naval victory of the war.[44]

In 247 BCE, Carthage appointed a new commander, Hamilcar Barca, to lead the land army in Sicily.[45] Although he was not given many men, by using hit-and-run, guerrilla tactics, he won victories against the Romans. With better resources provided by Carthaginian leadership, Hamilcar might have had even more success.[46]

In the meantime, using money borrowed from private citizens, the Romans had built 200 more ships which were commanded by the consul Gaius Lutetius Catullus.[47] In 241 BCE the Romans, using this fleet, defeated the Carthaginians at the Battle of Aegates Islands off the west coast of Sicily. Fifty Carthaginian ships were lost and 70 were captured.[48]

After this defeat, the Carthaginians sought peace terms. Under the resulting Treaty of Lutetius, Carthage withdrew entirely from Sicily and agreed to pay Rome 3200 talents of silver (an enormous sum).[49] Hamilcar Barca withdrew to Africa, where he was forced to fight what became known as the Mercenaries’ War, against Carthaginian mercenary troops rebelling against non-payment.[50] He was later sent to the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain), accompanied by his son-in-law, Hasdrubal, and his son, Hannibal.[51] Hannibal would become the leading Carthaginian figure in the Second Punic War.

Bibliography

Anglo Saxon Chronicle, trans. Rev. James Ingram. available at mcllibrary.org.

Boardman, J., Griffin, J., and Murray, O. eds. 1986 The Roman World. Oxford, U.K.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. De Natura Deorum 2.7. available at perseus.tufts.edu.

Goldsworthy, Adrian. 2000. The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC. London

Merriam-Webster Dictionary, History and Etymology for “Punic,” merriam-webster.com.

Polybius. The Histories. Book 1. available at perseus.tufts.edu. Available in English translation at gutenberg.org.

P. Vergilius Maro. Aeneid. available at perseus.tufts.edu.

Suetonius, Gaius Tranquillus. The Lives of the Caesars, Tiberius 2. available at perseus.tufts.edu.

Notes

1 Adrian Goldsworthy, 2000. The Fall of Carthage: The Punic Wars 265–146 BC 18. London.

2 Titus Livius (Livy), The Complete Works of Livy, trans. B. O. Foster and William A. McDevitte. 2014. Hastings, East Sussex; Appian, The Complete Works of Appian, trans. Horace White. 2016. Hastings, East Sussex.

3 P. Vergilius Maro, Aeneid 1.12–1.16. available at perseus.tufts.edu.

4 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 24.

5 Ibid., 27–28.

6 Merriam-Webster Dictionary, History and Etymology for Punic, merriam-webster.com.

7 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 38.

8 See, e.g., Boardman, J., Griffin, J., and Murray, O. eds., 1986. The Roman World 1-7. Oxford, U.K.

9 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 30.

10 Ibid., 43.

11 Ibid., 73.

12 Polybius, Histories 1.7. available at perseus.tufts.edu. or at gutenberg.org. With respect to the Vikings, the earliest date given for Viking raids in the Anglo Saxon Chronicle is 793 C.E. See Anglo Saxon Chronicle, trans. Rev. James Ingram. available at mcllibrary.org.

13 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 75-76; Polybius, Histories, 1.9–1.10.

14 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 76.

15 Ibid.; Polybius, Histories, 1.10.

17 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 82–83.

19 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 88.

21 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 48-49.

22 Ibid., 32.

23 Polybius, Histories, 1.20-1.21.

24 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 115-116.

26 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 126, 140.

28 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 130.

32 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 132-135.

33 Ibid., 136-137.

34 Ibid., 127.

42 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 144.

43 Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Natura Deorum, 2.7; Suetonius Gaius Tranquillus, Lives of the Caesars, Tiberius 2.

44 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 146.

45 Polybius, Histories, 1.56.

46 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 111.

47 Ibid., 150.

49 Goldsworthy, Fall of Carthage, 156–159.

50 Ibid., 161–165.

51 Ibid., 166–168.

Image credits

A reconstruction of what the ancient city of Carthage may have looked like, with its circular port. By “Shoestring” from Wikitravel. File: “An Imaginary Picture of Ancient Carthage.jpg.” Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Map: First Punic War. Image from Muir, Ramsay; Treharne R. F.; Fullard, Harold (1969). Muir’s Historical Atlas. London: George Philip and Son p. 11, map B. File: “First Punic War 264 BC.” Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. via Wikimedia Commons

An illustration of Carthaginian war elephants. By Henri-Paul Motte (1846-1922). File: “Carthaginian war elephants engage Roman infantry at the Battle of Zama (202 BC).” Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

A reconstructed Greek trireme, showing three decks of oars. Photograph by George E. Koronaios. 2020. File: “The trireme Olympias on September 1, 2020.” Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. via Wikimedia Commons

An illustration of a warship, showing the corvus at the upper left. By “Lutatius.”1991. File: “Trireme and Corvus.jpg.” Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0. via Wikimedia Commons

First published July 29.2021

Kelly Lambert is a participant at Kosmos Society.