A few weeks ago I watched the coronation of a king. At one point I noticed the king holding in his hands not one but two scepters. The mental image of Agamemnon holding his scepter involuntarily jumped into my thoughts and disturbed me briefly. Although there is probably no direct link, I decided to explore certain symbols of royalty in Homeric and Hesiodic poetry.

Scepters were used in the ancient world. The picture of the stela of The Code of Hammurabi at the Louvre shows the god Shamash holding a scepter. In Ancient Greece, the most powerful mythological king to possess a scepter is Zeus, the ultimate king. Other gods have one, like Apollo and Hermes.

No goddesses or mortal women seem to be described holding one, except maybe Aphrodite, Athena and also Hera, but on visual art.

Maybe the queen of the Phaeacians or Penelope, who both reign “like a good king,” could have one, but instead they have a distaff. King Priam has a scepter, and the priest Khrysēs comes to free his daughter with the scepter of Apollo. However, Agamemnon tells Khrysēs that his scepter will be useless, which means that he does not respect the divine order, and he will be soon punished for this act of injustice with the plague sent by Apollo.

Now Khrysēs had come to the ships of the Achaeans to free his daughter, and had brought with him a great ransom [apoina]: moreover he bore in his hand the scepter [skēptron] of Apollo wreathed with a suppliant’s wreath [15] and he besought the Achaeans, but most of all the two sons of Atreus, who were their chiefs. “…Your scepter [skēptron] of the god and your wreath shall profit you nothing. I will not free her.”

Iliad 1.11–16, 28–29, adapted from Sourcebook

Agamemnon received his scepter in a complex way. In Iliad 2 the history of Agamemnon’s scepter is detailed, and as often it was made by Hephaistos, the divine gifted craftsman.

Then powerful King Agamemnon rose, holding his scepter [skēptron]. It was the work of Hephaistos, who gave it to Zeus the son of Kronos. Zeus gave it to the courier Hermes, slayer of Argos, guide and guardian. King Hermes gave it to Pelops, the mighty charioteer, and [105] Pelops to Atreus, shepherd of his people. Atreus, when he died, left it to Thyestes, rich in flocks, and Thyestes in his turn left it to be borne by Agamemnon, that he might be lord of all Argos and of the isles. Leaning, then, on his scepter, he addressed the Argives.

Iliad 2.100–109, adapted from Sourcebook

However, this same scepter seems to be used by all the members of the different assemblies, speakers who pass it around and hold it when it is their turn to address the others.

In the following passage, from Iliad 1, Achilles is holding Agamemnon’s scepter as he is speaking.

|233 And here’s another thing. I’ll tell it to you, and I will swear on top of it a great oath: |234 I swear by this scepter [skēptron] that I’m holding here, this scepter that will never again have leaves and branches |235 growing out of it — and it never has — ever since it left that place in the mountains where it was cut down. |236 It will never flourish again, since the bronze implement has stripped it |237 of its leaves and its bark. Now the sons of the Achaeans carry it around, |238 holding it in their hands whenever they act as makers of judgments [dikaspoloi], judging what are and what are not divine laws [themis] …”… |245 Thus spoke [Achilles] the son of Peleus, and he threw the scepter [skēptron] to the ground, |246 that scepter adorned with golden studs driven into it. Then he sat down.

Iliad 1.232–246, Sourcebook

Achilles, in this passage, is showing not only that the staff is used by different kings but that the scepter is also used to swear an oath. This is not the only occurrence.

Furthermore there is an interesting detail in the passage above when Achilles in his anger throws the scepter: “…Thus spoke [Achilles] the son of Peleus, and he threw the scepter [skēptron] to the ground,” and we have a similar scene of rage when Telemachus also throws his scepter on the ground in Odyssey 2.

[80] With this Telemachus dashed his scepter [skēptron] to the ground and burst into tears. Every one was very sorry for him, but they all sat still and no one ventured to make him an angry answer, save only Antinoos…

Odyssey 2.80–84, adapted from Sourcebook

According to Beck (2005), Achilles is disgusted.

Moreover, the scepter σκῆπτρον figures in the narrator’s description of Achilles immediately after his speech. Achilles does not merely sit down, as several characters have already done when they finished speaking. Instead, he expresses the depth of his disgust with the whole proceeding by first throwing the σκῆπτρον to the ground and then sitting down.

Telemachus, who is young and seems helpless, might just be showing his frustration at not being able to obtain what he desires.

There is an amazing scene in the description of the Shield of Achilles where heralds give the elders scepters, ([skēptra] in the plural form), so that they can speak in turn and render justice. The place is sacred, and the word judgment [dikē] is used for the act of justice.

Meanwhile the people were gathered in assembly, and there a quarrel [neikos] 498 had arisen, and two men were quarreling [neikeîn] about the blood-price [poinē] 499 for a man who had died. One of the two claimed that he had the right to pay off the damages in full, [500] declaring this publicly to the population of the district [dēmos], and the other of the two was refusing to accept anything. 501 Both of them were seeking a limit [peirar], in the presence of an arbitrator [histōr], 502 and the people took sides, each man shouting for the side he was on; 503 but the heralds kept them back, and the elders 504 sat on benches of polished stone in a sacred [hieros] circle, [505] taking hold of scepters [skēptra] that the heralds, who lift their voices, put into their hands. 506 Holding these [scepters] they rose and each in his turn gave judgment [dikazein], 507 and in their midst there were placed on the ground two measures of gold, 508 to be given to that one among them who spoke a judgment [dikē] in the most straight way [ithuntata].

Iliad 18.497–509, Sourcebook

In Iliad 2 Odysseus uses Agamemnon’s scepter to urge the Achaeans and he even hits some of them with it. The scepter itself seems to embody the authority of the king of kings, Agamemnon. It commands respect and fear.

[185] whereon Odysseus went straight up to Agamemnon son of Atreus and received from him his ancestral, imperishable [aphthiton aiei] scepter [skēptron]. With this he went about among the ships of the Achaeans.

Whenever he met a king or chieftain, he stood by him and spoke to him fairly. [190]…But when he came across some man from some locale [dēmos] who was making a noise, he struck him with his scepter [skēptron] and rebuked him, saying, [200] “What kind of superhuman force [daimōn] has possessed you? Hold your peace, and listen to better men than yourself. You are a coward and no warrior; you are nobody either in fight or council; we cannot all be kings [basileus]; it is not well that there should be many masters [koiranos]; one man must be supreme— [205] one king [basileus] to whom the son of scheming Kronos has given the scepter [skēptron] and divine laws to rule over you all.”

Iliad 2.185–189, 198–206, adapted from Sourcebook

The expression “sceptered kings” is also used in Homeric poetry, both in the Iliad and the Odyssey.

With this he led the way from the assembly, [85] and the other sceptered [skēptoukhos] kings [basileus] rose with him in obedience to the word of Agamemnon;

Iliad 2.84–86, adapted from Sourcebook

The scepter being one of the attributes and symbols associated with royalty. It is also associated with justice and the well-being of people as shown with Minos, Nestor, and Agamemnon. There are many kings at Troy, but they all seem to borrow Agamemnon’s when they need to speak or to do justice or to discipline some warriors. The kings do not seem to have brought their own scepters from their royal kingdom. However, in the following passages Minos, in Hades, Nestor, in sandy Pylos, and Agamemnon use their own scepters.

568 There I saw Minos, radiant son of Zeus, 569 who was holding a golden scepter [skēptron] as he dispensed justice among the dead. [570] He was seated, while they [= the dead] asked the lord for his judgments [dikai]. 571 Some of them [= the dead] were seated, and some were standing, throughout the house of Hādēs, with its wide gates.

Odyssey 11.568–572, adapted from SourcebookNow when the child of morning, rosy-fingered Dawn, appeared, [405] Nestor, the charioteer of Gerenia, left his couch and took his seat on the benches of white and polished marble that stood in front of his house. Here aforetime sat Neleus, peer of gods in counsel, [410] but he was now dead, and had gone to the house of Hādēs; so Nestor of Gerenia sat in his seat, scepter [skēptron] in hand, as guardian of the public weal. His sons as they left their rooms gathered round him, Ekhephron, Stratios, Perseus, Aretos, and Thrasymedes; [415] the sixth son was the hero Peisistratos, and when godlike Telemachus joined them they made him sit with them. Nestor then addressed them.

Odyssey 3.404–417, adapted from Sourcebook“With yourself, most noble son of Atreus, king [anax] of men, Agamemnon, will I (Nestor) both begin my speech and end it, for you are king [anax] over many people. Zeus, moreover, has granted you to wield the scepter [skēptron] and to uphold what is right [themis] that you may take thought for your people under you.

Iliad 9.96–99, adapted from Sourcebook

There is a strange episode when the scepter is used by Odysseus as a weapon again, this time to hurt Thersites to restore royal order and divine laws, and make sure they are respected. Even if many kings are present at Troy, Odysseus seems to imply that Agamemnon alone is the supreme king to be obeyed, and he uses Agamemnon’s scepter as a cruel reinforcement of this rule. He even has the support of Athena as he wields the scepter.

[265] Then he beat him with his scepter [skēptron] about the back and shoulders till he dropped and fell weeping. The golden scepter [skēptron] raised a bloody welt on his back, so he sat down frightened and in pain, looking foolish as he wiped the tears from his eyes. [270] The people were sorry for him, but they laughed heartily, and one man would turn to his neighbor saying, “Odysseus has done many a good thing before now in fight and council, but he never did the Argives a better turn [275] than when he stopped this man’s mouth from barking any further. He will give the kings [basileus] no more of his insolence.”

Thus said the people. Then Odysseus, ransacker of cities, rose, scepter [skēptron] in hand, and owl-vision Athena [280] in the likeness of a herald bade the people be still, that those who were far off might hear him and consider his council. He therefore with all sincerity and goodwill addressed them…Iliad 2.265–183, adapted from Sourcebook

In Iliad 2.186 (quoted above) we have the scepter associated with the concept of being imperishable with the expression ἄφθιτον αἰεί [aphthiton aiei]. How can a simple staff incarnate an everlasting concept of power?

As in Hesiod’s Theogony the poet sings what is to last forever.

That is how they spoke, those daughters of great Zeus, who have words [epea] that fit perfectly together, 30 and they gave me a scepter [skēptron], a branch of flourishing laurel, 31 having plucked it. And it was a wonder to behold. Then they breathed into me a voice [audē], 32 a godlike one, so that I may make glory [kleos] for things that will be and things that have been, 33 and then they told me to sing how the blessed ones [makares = the gods] were generated, the ones that are forever [aiei], 34 and that I should sing them [= the Muses] first and last.

Hesiodic Theogony 29–34, adapted from Sourcebook

In Hesiod, there is also the association with the concept of being steadfast with the word asphalḗs. The scepter is a symbol of divinity. The Muses give a scepter to Hesiod, who is not a sceptered king but a sceptered poet. The shift is from kings to poets and then again from poets to kings, as Hesiod points out that a king speaks steadily: “ὁ δ’ ἀσφαλέως ἀγορεύων” (Hesiodic Theogony 86). The passage (80–100) in the Theogony is in a way similar to the scene on the Shield of Achilles. Kings or elders, like poets, preserve the order for ever through their words. The scepter is given by the divine Muses to Hesiod, and the kings pass the scepter around, and both with their gifted speech given by the divine Muses, keep the world steady, with their “asphalḗs speech”.

So the scepter of the Muses offered to the poet Hesiod signals the gift of asphalḗs speech. Other passages in which forms of émpedos occur show a connection with scepters. In each case the scepter signals the steadfast nature of the holder in a professional realm of influence. For instance, the seer Teiresias who has émpedoi phrénes even in death (Odyssey 10.493) is specifically depicted as still holding his scepter in the underworld (Odyssey 11.90–91).

Filos, Claudia, Steadfast in a Multiform Tradition: émpedos and asphalḗs in Homer and Beyond, 2.3

Filos evokes also the most sophisticated hypothesis from Muellner (see note) in her work: the poet must receive inspiration and a scepter from the Muses to compose his cosmology.

Muellner argues that the Theogony, which is a prooímion, struggles with its own prooímion, stumbling and having to restart multiple times before successfully proceeding with the cosmogenic myth above. He sees this stumbling as betraying “a concern about its starting point.” [44] This idea can be formulated in the poem’s own term. By composing these lines and successfully beginning the cosmogony, the poet has accomplished something like the first acts of creation; he has brought forth an ever-steadfast seat of security and authority—a hédos asphalès aieí—for the poem, the authority of Zeus, and the cosmos.

So within both the mythical narrative world and the world of performance, this hédos asphalès aieí is dependent upon the authority and skill of the poet. Yet there is a loop in the logic supporting this foundation. The poet is himself sustained and authorized by gifts from the divine Muses: his scepter and his divine voice, both granted specifically so that he might chant the Theogony (30–34). In fact, the inner poet of the narrative must eceive the divine inspiration and scepter of the Muses before a successful cosmogony can be attemptedFilos, Claudia, Steadfast in a Multiform Tradition: émpedos and asphalḗs in Homer and Beyond

(Note: Muellner 1996 The Anger of Achilles, particularly Chapter 3, “The Narrative Sequence of the Hesiodic Theogony.”)

I hope that you will join me in the forum to share some passages or photos.

Vocabulary

σκῆπτρον :”staff of a wanderer or mendicant, scepter of kings, priests, heralds, judges. When a speaker arose to address the assembly, a scepter was put into his hands by a herald. Fig., as a symbol of royal power and dignity, Il. 2.46; see also Od. 2.37, Od. 11.91″ (Autenrieth)

“sceptre, also spelled scepter, ornamented rod or staff borne by rulers on ceremonial occasions as an emblem of authority and sovereignty. The primeval symbol of the staff was familiar to the Greeks and Romans and to the Germanic tribes in various forms (baculus, “long staff”; sceptrum, “short staff”) and had various significances. The staff of command belonged to God as well as to the earthly ruler; there were the old man’s staff, the messenger’s wand, the shepherd’s crook, and, derived from it, the bishop’s, and so on.” (Britannica)

Additional terms

anax [ἄναξ (ϝάναξ), -ακτος] lord, king

aphthiton aiei [ἄφθιτον αἰεί] imperishable for ever

asphaleōs [ἀσφαλέως] without swerving, steadily

basileus [βᾰσῐλ-εύς, ὁ βασιλεύς, βασιλεύς, βασιλέως, ὁ], king

Related topics

Bibliography

Sourcebook: Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power. Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Sourcebook: Homeric Odyssey Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power. Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Beck, Deborah. 2005. Homeric Conversation. Hellenic Studies Series 14. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn- 3:hul.ebook:CHS_BeckD.Homeric_Conversation.2005

Sourcebook: Hesiodic Theogony: 1–115 Translated by Gregory Nagy, 116–1022 Translated by J. Banks and adapted by Gregory Nagy Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Filos, Claudia. Steadfast in a Multiform Tradition: émpedos and asphalḗs in Homer and Beyond

in Bers, Victor, et al., eds., Donum natalicium digitaliter confectum Gregorio Nagy septuagenario a discipulis collegis familiaribus oblatum Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Bers_etal_eds.Donum_Natalicium_Gregorio_Nagy.2012

Autenrieth: Georg Autenrieth. 1891. A Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges. New York. Harper and Brothers. Online at Perseus

LSJ: Liddell, Henry George, and Scott, Robert. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones, with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. 1940. Oxford. Clarendon Press. Online at Perseus

Article “Scepter” by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannic at https://www.britannica.com/art/scepter

Texts accessed June 2023

Image credits

The Code of Hammurabi stela depicting the god Shamash holding a staff c 1793–c 1751 BCE. Louvre.

Photo: sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Zeus and Hermes, c 540–520 BCE

description from British Museum: ” Zeus seated to right, bearded, with long hair, fillet, long chiton and himation, the former embroidered with white rosettes, and both with purple spots; in right hand he holds a sceptre terminating in a Gryphon’s head, in left a ball (?). … In front of Zeus is Hermes departing to right and looking back at him. He is bearded, with long tresses, and wears a petasos (broad-rimmed hat), short chiton, embroidered with white rosettes, chlamys, and endromides (boots); his left hand is raised, in right he holds a caduceus (staff), with which he touches Zeus.”

Photo: ArchaiOptix, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

Venus. A medallion painting from the House of Marcus Fabius Rufus in Pompeii. Venus. 1st century BCE.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

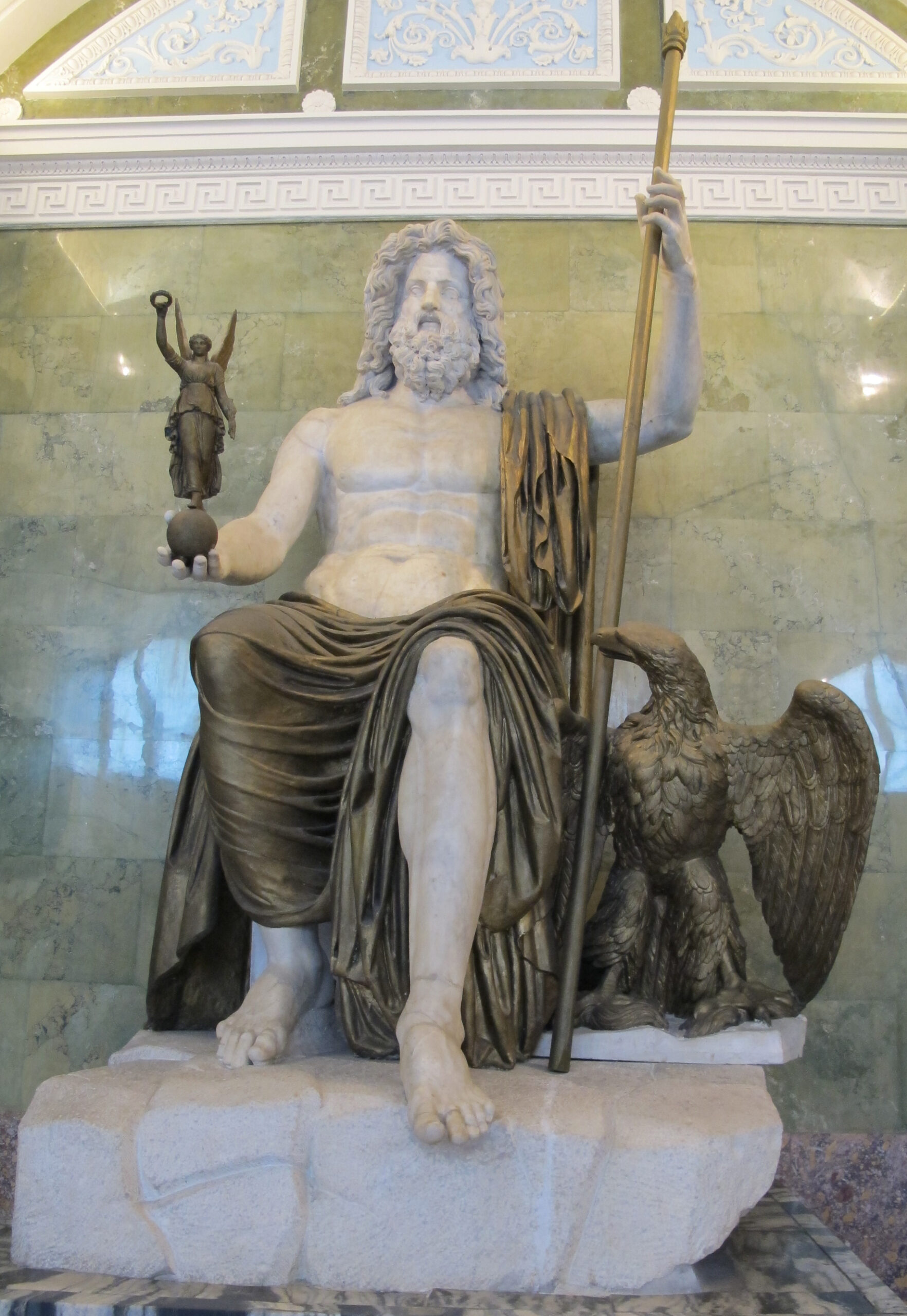

Bronze statue of Zeus

Photo: sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Achilles wrapped in a himation, Greek kylix, c 500 BCE.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Agamemnon seated on a rock and holding his sceptre, identified from an inscription. Fragment of the lid of an Attic red-figure lekanis by the circle of the Meidias Painter, 410–400 BCE

Photo: Jastrow, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Belly, Agamemnon roi des rois, Drawing in a book, Département des Arts Graphiques, Louvre. Photo: Kosmos Society

Images accessed June 2023

___

Hélène Emeriaud is a member of Kosmos Society