Three great battles—Mantinea (418 BCE), Leuctra (371 BCE), and Gaugamela (331 BCE)—demonstrate the development of Greek and Macedonian warfare from the simple hoplite phalanx employed by Greek farmers defending their fields, into the powerful, tactically flexible army which allowed Alexander the Great to conquer the Persian Empire. Arising at some point toward the end of the Dark Ages (approximately 800 BCE to 600 BCE), the phalanx of farmers armed with large round shield, seven-foot spear and helmet changed little during the first few centuries of its existence. During the hundred years from 431 to 331 BCE, however, the phalanx evolved into a mobile, disciplined, tactically-flexible force, that supplemented by cavalry and light infantry, provided a talented general with the capability of meeting and triumphing over any other army of its day.

Hoplite Warfare

As Greece awoke from its “Dark Ages”, it experienced a “military renaissance” centered on the hoplite—the heavily armed infantryman of the city-state [polis; plural poleis].[1] The hoplite, arranged side by side with his fellow citizens in a tightly packed phalanx, became the standard Greek fighting formation by the middle of the seventh century.

The small farmers of the early Greek polis needed a quick and cost-effective form of warfare to establish ownership of frontier land.[2] The phalanxes of two adversarial poleis would meet at the disputed territory, charge directly at each other and fight it out in the space of an afternoon. Eventually, one of the phalanxes would give way, and the other would chase the defeated enemy for only a short distance. Although the phalanx was supported by lightly armed infantrymen fighting with javelins and bows and lightly armored cavalrymen with javelins, these troops did not play a decisive role in battle. Hoplite warfare was conducted by the city states of central and southern Greece in this manner from approximately 700 BCE down to the beginning of the Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE.[3]

Tactics in major hoplite battles were essentially limited to a frontal attack. Victory for these armies of citizen-farmers was generally determined by bravery and staying-power. The side which could outlast its enemy and stand up better to the noise, fear, and blood of combat would gain the victory.[4]

The great Peloponnesian War which began in 431 BCE, which pitted Sparta and her allies against Athens and her Aegean empire, changed the nature of warfare. The length of the war, the high stakes involved, and the increasing death toll caused the usual forms of war to be abandoned. The participants began to search for an effective means of defeating the enemy beyond simple grit and bravery.[5]

The Advantage of Professionalism—Mantinea 418 BCE

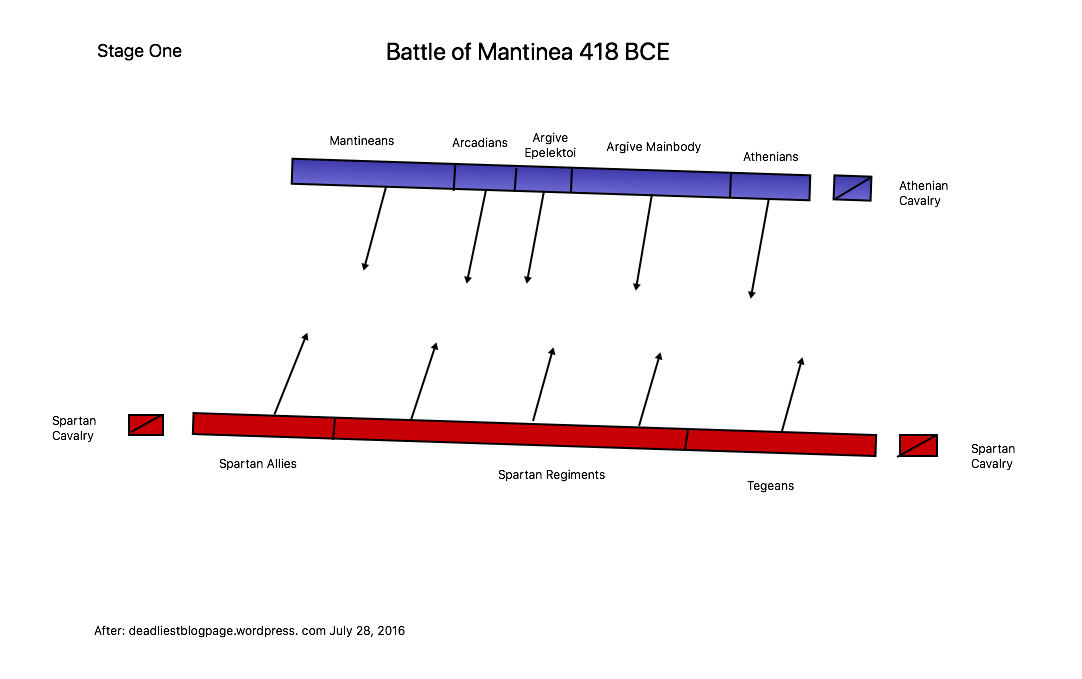

The battle of Mantinea was fought between the Peloponnesian League headed by Sparta, and a coalition of Mantinea, Argos, Athens and some others. The armies approached each other in the summer of 418 on the plain near Mantinea. The coalition army arranged one city’s phalanx next to its neighbor in one long line. On the Spartan side, the six Spartan “regiments” were joined by their allies and more informal groups of Spartans in a matching line of phalanxes (see Mantinea map, ‘Stage One’). As was the common practice, the strongest units were placed on each army’s right wing, the “place of honor”.

Most traditional hoplite battles began in essentially the same way. As expressed by the Greek historian Thucydides,

All armies are alike in this: on going into action they get forced out rather on their right wing…because fear makes each man do his best to shelter his unarmed side with the shield of the man next to him on the right.[6]

In other words, each army drifted to the right as it advanced, allowing each stronger right wing to envelop the enemy’s weaker left wing, enabling it to attack the enemy’s open flank.

The militia armies of citizen-solders were not highly trained, and had difficulty moving in any direction but forward. The Spartans were different: they were professionals, trained in arms and in maneuver. Their phalanx was composed of regiments, and the regiments of companies, and so on, each commanded by an officer. This professionalism allowed their phalanx a degree of maneuverability which they put to good use at Mantinea.

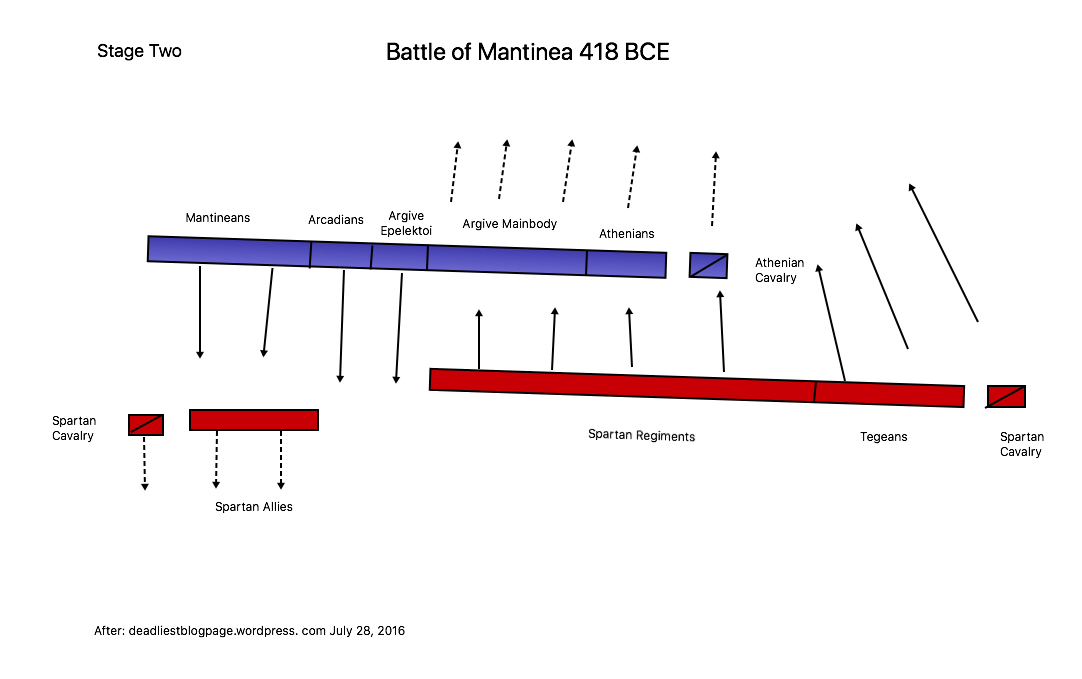

As the two armies marched towards each other, the traditional right drift caused the Spartan’s right wing to extend beyond the coalition’s left. But as the rightward movement of the coalition army began to overlap the Spartan left, the Spartan king Agis, “…afraid of his left being surrounded…ordered (them) to move out from their place in the ranks and make the line even.”[7] In doing so, a gap opened up within the Spartan left wing, offering the converging coalition right wing the opportunity to flank both sides of the Spartan’s left (see map, ‘Stage Two’). Given their advantage, the coalition right wing broke the Spartan left, and “cut up and surrounded the Spartans, and drove them in full rout…”

But on the other wing, the Spartans had the advantage over the coalition, and “instantly routed them; the greater number not even waiting to strike a blow, but giving way the moment that they came on…”[8]

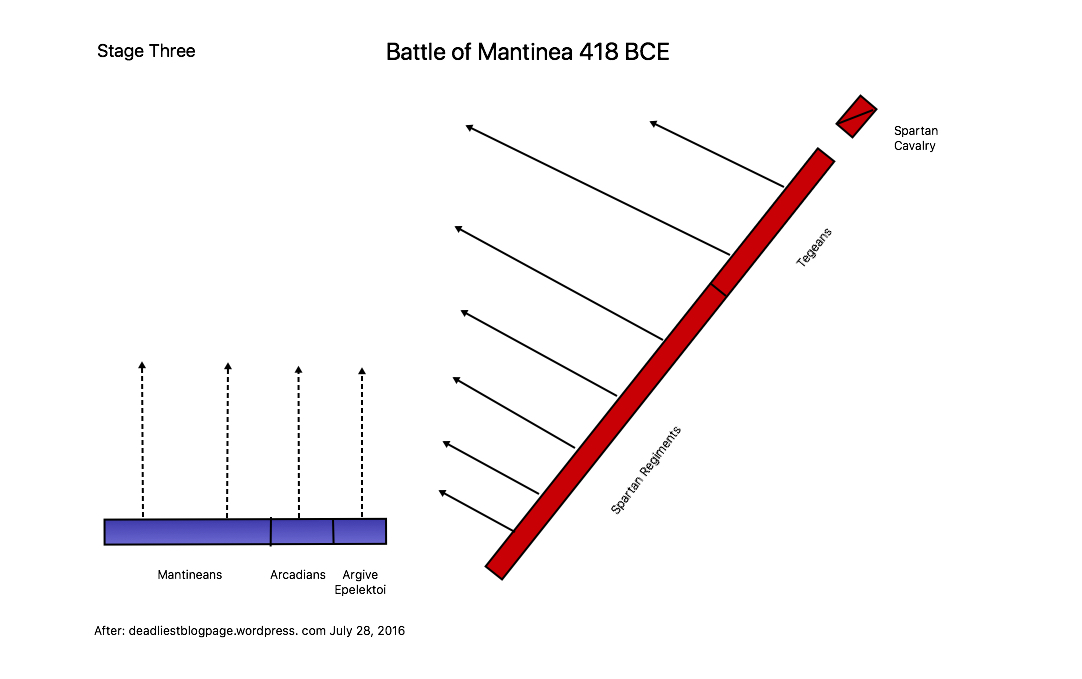

As the coalition left was being routed, Agis noticed the defeat of his own left wing, and “ordered all the army to advance to the support of the defeated wing…” And here, the Spartan training paid off, for they were able to swing their right wing around so that it pointed diagonally toward the coalition left wing, in effect making a change of front, and then advanced towards the enemy. As Thucydides writes, “the Mantineans and their allies…ceased to press the enemy, and seeing their friends defeated and Spartans in full advance upon them, took to flight”[9] (see map, ‘Stage Three’).

The training and professionalism of the Spartan regiments demonstrated their superiority over the citizen militia of the rest of Greece. No other hoplite army of that time would have been able to effect a change of front so efficiently and quickly, and turn a doubtful battle into a complete victory. Professionalism demonstrated one method of transforming hoplite warfare.

Coming next:

Part 2: Leuctra and Gaugamela

Notes

[1] V. D. Hanson, Wars of the Ancient Greeks, Smithsonian 2004, p.46

[2] Hanson, p.47

[3] A. Jones, The Art of War in the Western World, Oxford 1989 p.4

[4] J. E. Lendon, Soldiers and Ghosts, Yale 2005, p.52

[5] S. Hornblower, The Greek World, Routledge 2004, p.190

[6] Strassler, The Landmark Thucydides, Free Press 1996, Book 5.71

[7] Strassler, Thucydides Book 5.71

[8] Strassler, Thucydides Book 5.73

[9] Strassler, Thucydides Book 5.74

Bibliography

Arrian of Nicomedia, ‘The Anabasis of Alexander‘ translated by Chinnock, E.J. (en.wikisource.org)

Jones, A. 1989. The Art of War in the Western World, Oxford

Lendon, J. E. 2005. Soldiers & Ghosts, Yale

Pomeroy, Burstein, et al. 2008. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History, Oxford

Hanson, V. D. 2004. Wars of the Ancient Greeks, Smithsonian

Hornblower, S. 2008. The Greek World 479 – 322 B.C., Routledge

Strassler, R. B. 1996. The Landmark Thucydides, Free Press

Strassler, R. B. 2009. The Landmark Xenophon’s Hellenika, Pantheon Books

Image credits

Location map: Google maps

Battle plans: Ian Joseph, after deadliestblogpage.wordpress.com

Featured image: Dan Diffendale (photo) Chigi Vase, detail 1: hoplite battle, c 650-640 BCE, via Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

________________

Ian Joseph is a retired finance executive with an interest in ancient Greek history and literature. He received a BA in cultural anthropology from the University of Chicago and an MBA from Pepperdine University.

First published April 16, 2018