In Part 1 we looked at the role of aoidoi as depicted within epic poetry itself. Now we turn to later sources in which the word rhapsode comes into use.

In that post, we touched on the performance of Achilles and Patroklos in relay. Gregory Nagy comments:

8§28…Homeric poetry was performed at the Panathenaia by rhapsōidoi, ‘rhapsodes’ … The rhapsodes narrated the Iliad and Odyssey in relay, following traditions of rhapsodic sequencing: each rhapsode waited for his turn to pick up the narrative where the previous rhapsode left off … And the competition of rhapsodes in performing by relay and in sequence the Iliad and Odyssey of Homer at the festival of the Panathenaia was a ritual in and of itself. …

8§30. This is not to make a specific argument about the dating of Text E [= Iliad 9.185–195], the Iliadic passage showing Achilles and Patroklos performing in relay: it would be a mistake, I think, to date the wording of this passage to such a relatively late era, the sixth century BCE. After all, the tradition of rhapsodic relay was already at work in the Homeric tradition as it was evolving in the eighth and seventh centuries BCE at the festival of the Panionia. My general argument, rather, is that this tradition of rhapsodic relay, where rhapsodes collaborate as well as compete in the process of performing successive parts of integral compositions like the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey, can be used to explain the unity of these epics as they evolved over time.Gregory Nagy The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, Hour 8[1]

The word rhapsōdos [ῥαψῳδός] “performer of epic poems” comes from the verb rhaptō [ῥάπτω] “sew, stitch together; devise” + aoidē [ἀοιδή] “song”.

Although he does not use the word rhapsode, Pindar does provide references to them. For example, in Nemean 2, for Timodemus of Acharnae Pancratium, composed around 485 BCE:

ὅθεν περ καὶ Ὁμηρίδαι

ῥαπτῶν ἐπέων τὰ πόλλ᾽ ἀοιδοὶ

ἄρχονται, Διὸς ἐκ προοιμίου: καὶ ὅδ᾽ ἀνὴρ

καταβολὰν ἱερῶν ἀγώνων νικαφορίας δέδεκται πρῶτον Νεμεαίου

ἐν πολυυμνήτῳ Διὸς ἄλσει.Just as the Homeridae, the singers of woven verses, most often begin with Zeus as their prelude, so this man has received a first down-payment of victory in the sacred games by winning in the grove of Nemean Zeus, which is celebrated in many hymns.

Pindar Nemean 2.1–5, translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien[2]

We see both the verb and the noun used in the same verse, indicating how the Homeridae, who performed Homeric epic, were weaving together their song and performance.

The rhapsodes as performers of epic poetry were part a long oral tradition, using composition in performance as identified by Milman Parry and described in Albert B. Lord Singer of Tales.[3] There is evidence that they specialized in performing particular genres, so apart from the Homeridae there were others who performed Hesiodic poetry. In Plato’s Ion we encounter a rhapsode who is asked about why he performs only Homeric poetry:

Socrates

Then how is it that you are skilled in Homer, and not in Hesiod or the other poets? Does Homer speak of any other than the very things that all the other poets speak of? Has he not described war for the most part, and the mutual intercourse of men, good and bad, lay and professional, and the ways of the gods in their intercourse with each other and with men, and happenings in the heavens and in the underworld, and origins of gods and heroes?Ion 531c, translated by W.R.M. Lamb

[Socrates is speaking about “rings” through which power of poetry is transmitted]

You, the rhapsode and actor, are the middle ring; the poet himself is the first; but it is the god who through the whole series draws the souls of men whithersoever he pleases, making the power of one depend on the other. And, just as from the magnet, there is a mighty chain of choric performers and masters and under-masters suspended by side-connections from the rings that hang down from the Muse. One poet is suspended from one Muse, another from another: the word we use for it is “possessed,” but it is much the same thing, for he is held. And from these first rings—the poets—are suspended various others, which are thus inspired, some by Orpheus and others by Musaeus; but the majority are possessed and held by Homer. Of whom you, Ion, are one, and are possessed by Homer; and so, when anyone recites the work of another poet, you go to sleep and are at a loss what to say; but when some one utters a strain of your poet, you wake up at once, and your soul dances, and you have plenty to say: for it is not by art or knowledge about Homer that you say what you say, but by divine dispensation and possession; just as the Corybantian worshippers are keenly sensible of that strain alone which belongs to the god whose possession is on them, and have plenty of gestures and phrases for that tune, but do not heed any other. And so you, Ion, when the subject of Homer is mentioned, have plenty to say, but nothing on any of the others.Ion 536a–536c, translated by W.R.M. Lamb[4]

Apart from epic another specialism was the performance of Homeric Hymns. Ann Bergren provides an analysis of their development in performance:

From the beginning, the Homeric hymns mark both beginning and end. They come before the recitation of epic, but after Homeric epic has reached its peak. The evidence is scanty, but so far as we can tell, the works in this somewhat paradoxical category of “Homeric hymn” represent an elaboration by the rhapsodes of the invocation that had traditionally begun an epic song. Demodocus, at the start of his third song at Phaeacia, is said to “begin from the god” or “goddess” (Odyssey viii 499). Similarly, the Homeridae, according to Pindar Nemean 2.1–3, “generally begin their woven epics with a prooimion to Zeus,” the same term “prooimion” with which Thucydides (3.104) in our earliest explicit reference to the hymns designates the Homeric Hymn to Apollo. According to the scholiast on Nemean 2.1 (3.28.16–3.29.18 Drachmann), the Homeridae were “originally sons of Homer who sang by right of succession” and later rhapsodes who performed Homeric epic without claiming direct descent. The Homeridae performed at such contests as those described in the Contest Between Homer and Hesiod, local gatherings like the funeral at Chalcis where Hesiod triumphed (see also Works and Days 654–659) and larger festivals like the panêguris at Delos (see also Hesiod fr. 357 MW). While questionable as biography, the Contest does seem to preserve a plausible picture of the process by which the works of the poets canonized as “Homer” and “Hesiod” were gradually disseminated and finally fixed in their Panhellenic form. So we have this chain of evidence: Demodocus begins his song with an invocation of the deity; the “sons of Homer” who recite epic at contests during the period of its progressive fixation begin with a prooimion to Zeus; and our earliest reference to a Homeric hymn is as a prooimion. {131|132}

This evidence, to quote the commentary of Allen, Halliday, and Sykes (1936:lxxxviii–lxxxix) seems “to show the ‘Homeric hymn’ in the light of a πάρεργον of the professional bard or rhapsode, as delivered at an ἀγών, whether at a god’s festival or in honor of a prince.” The Homeric hymn is a πάρεργον “subordinate or secondary business” of the “sons of Homer” in relation to their primary job of repeating the father’s words. A πάρεργον, yes, but not merely so, for as the major hymns of the corpus testify, this “preface” develops into a genre in its own right, and it does so as the paternal genre declines. The period and the process of the dispersal, fixation, and Panhellenization of Homeric epic is also the period and process of epic’s decline. During that period, the agents of the process, the “sons of Homer,” develop the old preface into a genre of their own. The old beginning of Homeric epic begins as a vital genre when Homeric epic ends.

Ann Bergren Weaving Truth: Essays on Language and the Female in Greek Thought, “6. Sacred Apostrophe: Re-Presentation and Imitation in Homeric Hymn to Apollo and Homeric Hymn to Hermes,” I. Genre and History[5]

Homeric epic became enshrined as part of the Panathenaia in an established form, according to evidence from Lycurgus, an Athenian orator (390–324 BCE):

I want also to recommend Homer to you. In your fathers’ eyes he was a poet of such worth that they passed a law that every four years at the Panathenaea he alone of all the poets should have his works recited*; and thus they showed the Greeks their admiration for the noblest deeds. They were right to do so. Laws are too brief to give instruction: they merely state the things that must be done; but poets, depicting life itself, select the noblest actions and so through argument and demonstration convert men’s hearts.

* [= footnote by J.O. Burtt] The law that Homer should be recited at the festival of the Great Panathenaea, held in the third year of each Olympiad, may fairly safely be assigned to the time of the Pisistratids (c. 560 to 510 B.C.). It is not mentioned in connection with Pisistratus himself, though he is credited by a number of ancient authorities with the establishment of a definite text of Homer (cf. Cicero,de Orat. 3.34), but according to Plat. Hipparch. 228b, his son Hipparchus did provide for recitations at the festival.

Lycurgus 1.102, translation and footnote by J.O. Burtt[6]

Despite this, the law could work the other way, as we see in this passage from Herodotus 5.67.1 about the interdiction by Cleisthenes (who ruled at Sicyon from 600 to 570 BCE) of rhapsodes reciting Homeric poetry.

ταῦτα δέ, δοκέειν ἐμοί, ἐμιμέετο ὁ Κλεισθένης οὗτοςτὸν ἑωυτοῦ μητροπάτορα Κλεισθένεα τὸν Σικυῶνοςτύραννον. Κλεισθένης γὰρ Ἀργείοισι πολεμήσας τοῦτο μὲν ῥαψῳδοὺς ἔπαυσε ἐν Σικυῶνιἀγωνίζεσθαι τῶν Ὁμηρείων ἐπέων εἵνεκα, ὅτι Ἀργεῖοί τε καὶ Ἄργος τὰ πολλὰ πάντα ὑμνέαται: τοῦτο δέ, ἡρώιον γὰρ ἦν καὶ ἔστι ἐν αὐτῇ τῇ ἀγορῇτῶν Σικυωνίων Ἀδρήστου τοῦ Ταλαοῦ, τοῦτονἐπεθύμησε ὁ Κλεισθένης ἐόντα Ἀργεῖον ἐκβαλεῖν ἐκτῆς χώρης.

In doing this, to my thinking, this Cleisthenes was imitating his own mother’s father, Cleisthenes the tyrant of Sicyon, for Cleisthenes, after going to war with the Argives, made an end of minstrels’ contests at Sicyon by reason of the Homeric poems, in which it is the Argives and Argos which are primarily the theme of the songs. Furthermore, he conceived the desire to cast out from the land Adrastus son of Talaus, the hero whose shrine stood then as now in the very marketplace of Sicyon because he was an Argive.

Herodotus 5.67.1 translated by A.D. Godley[7]

That the rhapsodes had contests is still in evidence by the time of Plato’s Ion: at the opening of the dialogue, Ion tells Socrates that he has come from a festival of Asclepius at Epidaurus, and that he took first prize. Socrates also wishes him luck at the Panathenaea.[8]

From Isocrates, another Athenian orator (436–338 BCE), we hear a criticism of the skill of rhapsodes:

ἀπαντήσαντες γάρ τινές μοι τῶν ἐπιτηδείων ἔλεγον ὡς ἐν τῷΛυκείω συγκαθεζόμενοι τρεῖς ἢ τέτταρες τῶν ἀγελαίων σοφιστῶν καὶπάντα φασκόντων εἰδέναι καὶ ταχέως πανταχοῦ γιγνομένων διαλέγοιντο περί τε τῶν ἄλλων ποιητῶν καὶ τῆς Ἡσιόδου καὶ τῆς Ὁμήρου ποιήσεως, οὐδὲν μὲν παρ᾽ αὑτῶν λέγοντες, τὰ δ᾽ ἐκείνων ῥαψῳδοῦντες καὶ τῶν πρότερον ἄλλοις τισὶν εἰρημένων τὰ χαριέστατα μνημονεύοντες:

For some of my friends met me and related to me how, as they were sitting together in the Lyceum, three or four of the sophists of no repute—men who claim to know everything and are prompt to show their presence everywhere—were discussing the poets, especially the poetry of Hesiod and Homer, saying nothing original about them, but merely chanting their verses and repeating from memory the cleverest things which certain others had said about them in the past.

Isocrates 12.18 translated by George Norlin[9]

Here are two further passages about the skills of rhapsodes.

In Xenophon’s Symposium a group of friends have been listening to a musician play, and the conversation turns to what each participant considers the most useful skill or knowledge they possess:

ἀλλὰ σὺ αὖ, ἔφη, λέγε, ὦ Νικήρατε, ἐπὶ ποίᾳ ἐπιστήμῃ μέγα φρονεῖς. καὶ ὃς εἶπεν: ὁ πατὴρ ὁ ἐπιμελούμενος ὅπως ἀνὴρ ἀγαθὸς γενοίμην ἠνάγκασέ με πάντα τὰ Ὁμήρου ἔπη μαθεῖν: καὶ νῦν δυναίμην ἂν Ἰλιάδα ὅλην καὶ Ὀδύσσειαν ἀπὸ στόματος εἰπεῖν. {6}ἐκεῖνο δ᾽, ἔφη ὁ Ἀντισθένης, λέληθέ σε, ὅτι καὶ οἱ ῥαψῳδοὶ πάντες ἐπίστανται ταῦτα τὰ ἔπη; καὶ πῶς ἄν, ἔφη, λελήθοι ἀκροώμενόν γε αὐτῶν ὀλίγου ἀν᾽ ἑκάστην ἡμέραν; οἶσθά τι οὖν ἔθνος, ἔφη, ἠλιθιώτερον ῥαψῳδῶν; οὐ μὰ τὸν Δί᾽, ἔφη ὁ Νικήρατος, οὔκουν ἔμοιγε δοκῶ. δῆλον γάρ, ἔφη ὁ Σωκράτης, ὅτι τὰς ὑπονοίας οὐκ ἐπίστανται. σὺ δὲ Στησιμβρότῳ τε καὶ Ἀναξιμάνδρῳ καὶ ἄλλοις πολλοῖς πολὺ δέδωκας ἀργύριον, ὥστε οὐδέν σε τῶν πολλοῦ ἀξίων λέληθε.

And so, Niceratus,” he [= Socrates] suggested, “it is your turn; tell us what kind of knowledge you take pride in.”

“My father was anxious to see me develop into a good man,” said Niceratus, “and as a means to this end he compelled me to memorize all of Homer; and so even now I can repeat the whole Iliad and the Odyssey by heart.”

{6} “But have you failed to observe,” questioned Antisthenes, “that the rhapsodes, too, all know these poems?”

“How could I,” he replied, “when I listen to their recitations nearly every day?”

“Well, do you know any tribe of men,” went on the other, “more stupid than the rhapsodes?”

“No, indeed,” answered Niceratus; “not I, I am sure.”

“No,” said Socrates; “and the reason is clear: they do not know the inner meaning of the poems. But you have paid a good deal of money to Stesimbrotus, Anaximander, and many other Homeric critics, so that nothing of their valuable teaching can have escaped your knowledge.”

Xenophon Symposium 3.5–6 [translator not given on Perseus][10]

Athenaeus, an author of the 3rd-century CE from Egypt, also structures The Deipnosophists as a dialogue, based on a conversation at a banquet given by Laurentius, a noble Roman. The discussions incorporate quotations from ancient poetry and prose. Here the speaker describes part of the entertainment and a discussion about the repertoire of rhapsodes: it is a more favorable account than the opinion of Socrates as presented by Xenophon in the previous passage or in Plato’s Ion.

“12. οὐκ ἀπελείποντο δὲ ἡμῶν τῶν συμποσίων οὐδὲ ῥαψῳδοί. ἔχαιρε γὰρ τοῖς Ὁμήρου ὁ Λαρήνσιος ὡς ἄλλος οὐδὲ εἷς, ὡς λῆρον ἀποφαίνειν Κάσανδρον [p. 340] τὸν Μακεδονίας βασιλεύσαντα, περὶ οὗ φησι Καρύστιος ἐν Ἱστορικοῖς Ὑπομνήμασιν ὅτι οὕτως ἦν φιλόμηρος ὡς διὰ στόματος ἔχειν τῶν ἐπῶν τὰ πολλά καὶ Ἰλιὰς ἦν αὐτῷ καὶ Ὀδυσσεία ἰδίως γεγραμμέναι. ὅτι δ᾽ ἐκαλοῦντο οἱ ῥαψῳδοὶ καὶ Ὁμηρισταὶ Ἀριστοκλῆς εἴρηκεν ἐν τῷ περὶ Χορῶν. τοὺς δὲ νῦν Ὁμηριστὰς ὀνομαζομένους πρῶτος εἰς τὰ θέατρα παρήγαγε Δημήτριος ὁ Φαληρεύς.

χαμαιλέων δὲ ἐν τῷ περὶ Στησιχόρου καὶ μελῳδηθῆναί φησιν οὐ μόνον τὰ Ὁμήρου, ἀλλὰ καὶ τὰ Ἡσιόδου καὶ Ἀρχιλόχου, ἔτι δὲ Μιμνέρμου καὶ Φωκυλίδου. Κλέαρχος δ᾽ ἐν τῷ προτέρῳ περὶ Γρίφων ‘τὰ Ἀρχιλόχου, φησίν, Σιμωνίδης ὁ Ζακύνθιος ἐν τοῖς θεάτροις ἐπὶ δίφρου καθήμενος ἐρραψῴδει.’ Λυσανίας δ᾽ ἐν τῷ πρώτῳ περὶ Ἰαμβοποιῶν Μνασίωνα τὸν ῥαψῳδὸν λέγει ἐν ταῖς δείξεσι τῶν Σιμωνίδου τινὰς ἰάμβων ὑποκρίνεσθαι. τοὺς δ᾽ Ἐμπεδοκλέους Καθαρμοὺς ἐρραψῴδησεν Ὀλυμπίασι Κλεομένης ὁ ῥαψῳδός, ὥς φησιν Δικαίαρχος ἐν τῷ Ὀλυμπικῷ. Ἰάσων δ᾽ ἐν τρίτῳ περὶ τῶν Ἀλεξάνδρου Ἱερῶν ἐν Ἀλεξανδρείᾳ φησὶν ἐν τῷ μεγάλῳ θεάτρῳ ὑποκρίνασθαι Ἡγησίαν τὸν κωμῳδὸν τὰ Ἡσιόδου, Ἑρμόφαντον δὲ τὰ Ὁμήρου. ”

Moreover, there were rhapsodists also present at our entertainments: for Laurentius delighted in the reciters of Homer to an extraordinary degree; so that one might call Cassander the king of Macedonia a trifler in comparison of him; concerning whom Carystius, in his Historic Recollections, tells us that he was so devoted to Homer, that he could say the greater part of his poems by heart; and he had a copy of the Iliad and the Odyssey written out with his own hand. And that these reciters of Homer were called Homeristæ also, Aristocles has told us in his treatise on Choruses. But those who are now called Homeristæ were first introduced on the stage by Demetrius Phalereus.

Now Chamæleon, in his essay on Stesichorus, says that not only the poems of Homer, but those also of Hesiod and Archilochus, and also of Mimnermus and Phocylides, were often recited to the accompaniment of music; and Clearchus, in the first book of his treatise on Pictures, says—“Simonides of Zacynthus used to sit in the theatres on a lofty chair reciting the verses of Archilochus.” And Lysanias, in the first book of his treatise on Iambic Poets, says that Mnasion the rhapsodist used in his public recitations to deliver some of the Iambics of Simonides. And Cleomenes the rhapsodist, at the Olympic games, recited the Purification of Empedocles, as is asserted by Dicæarchus in his history of Olympia. And Jason, in the third book of his treatise on the Temples of Alexander, says that Hegesias, the comic actor, recited the works of Herodotus in the great theatre, and that Hermophantus recited the poems of Homer.

Athenaeus. The Deipnosophists 14.12, translated by C. D. Yonge[11]

These selections provides some evidence for the performances of rhapsodes, their repertoire, and how their skills were viewed. What else are you finding about rhapsodes? Please join the discussion in the forum.

Notes

[1] H24H: Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA: 2013. Available online at The Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[2] Greek text from Sandys, John. 1937. Pindar. The Odes of Pindar including the Principal Fragments with an Introduction and an English Translation by Sir John Sandys, Litt.D., FBA. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

English translation: Odes. Pindar. Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

[3] Lord, Albert B. 1960, 2000. The Singer of Tales. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, Massachussets; London, England. Online edition available at The Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_LordA.The_Singer_of_Tales.2000

[4] Plato. Lamb, W.R.M. 1925. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Volume 9. translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Available on Perseus.

[5] Bergren, Ann. 2008. Weaving Truth: Essays on Language and the Female in Greek Thought. Hellenic Studies Series 19. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. Available online at The Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_BergrenA.Weaving_Truth.2008

[6] Lycurgus. from Burtt, J.O. 1962 Minor Attic Orators in two volumes, 2 with an English translation by J. O. Burtt, M.A. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Available on Perseus.

[7] Herodotus. Godley, A.D. 1920. Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press.

Available on Perseus.

[8] Plato Ion, 530a–b. Plato lived from c 428–c 347 BCE; this is probably an early dialogue.

[9] Isocrates. Norlin, George. 1980. Isocrates with an English Translation in three volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd.

Available on Perseus.

[10] Xenophon in Seven Volumes, 4. 1979. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA; William Heinemann, Ltd., London.

Available at Perseus.

[11] Athenaeus. Greek text: Gulick, Charles Burton. 1927. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. William Heinemann, Ltd., London.

Available at Perseus.

Translation: Yonge, C.D. 1854. The Deipnosophists. Or Banquet Of The Learned Of Athenaeus. London. Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden.

Available at Perseus.

Online texts accessed November 2018.

Image credits

Detail from decoration on red-figured neck-amphora depicting a victorious poet reciting. British Museum 1843,1103.34. circa 490BCE–480BCE. Attributed to the Kleophrades Painter. The inscription underneath the figure says KAΛΟNEI [καλος εΐ], “he is handsome” and the words coming from his mouth say ΗΟΔΕΠΟΤΕΝΤYPIΝΘI [Ωδε ποτ έv Tύρινθι], “As once in Tiryns…”, as the first words of a metrical poem. (Details summarized from description by the British Museum.) Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) © The Trustees of the British Museum

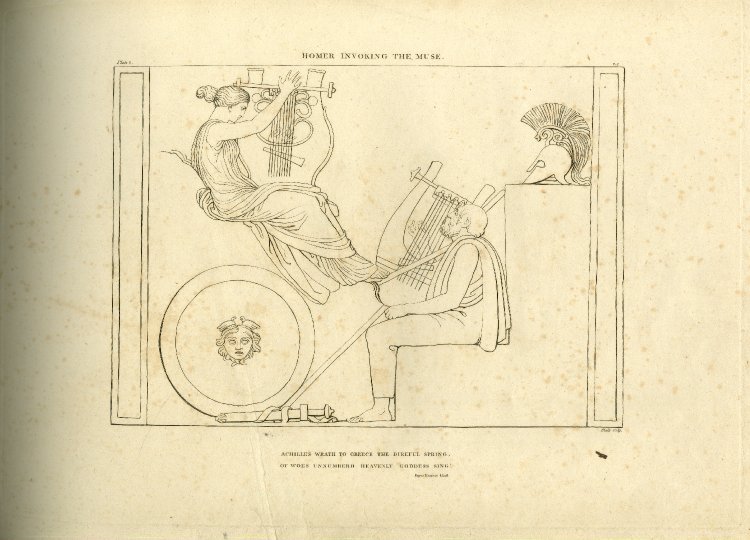

Print by William Blake, after John Flaxman. Homer invoking the Muse. Illustration for the Iliad of Homer. 1805. British Museum. 1973,U.1189.2 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) © The Trustees of the British Museum

Jean-Baptiste Auguste Leloir: Homère. 1841. Louvre. Photo: Neuceu, Creative Commons CC-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Anselm Feuerbach: Das Gastmahl. (The Symposium). 1871–1874. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website. Images accessed November 2018.

First published November 14, 2018

Hélène Emeriaud, Janet Ozsolak, and Sarah Scott are members of the Kosmos Society.