My trip to Naples—planned months ago—had not been cancelled; I could hardly believe it. Up to the last minute I was not sure whether the Foreign Office would advise against trips to Italy or not. But there I was in the Parthenopean city, and thinking of how to get from Naples to Paestum (pronounced [pestum] in Italian), which I had not visited before.

On the appointed day, Domenico, my driver, who not only did the driving but also talked volubly, through his facemask, and gesticulating at the same time—I kept thinking: oh please watch the road! —told me how, when he was a child, he used to visit the site of the Greek temples in Paestum with his father and how fascinated he had been every time. As he pulled up on the road along the site, after a two hours’ drive south of Naples, I saw the three temples rising majestically from the immense plain of the river Sele, and I knew immediately what he meant.

As one enters the vast site, one has a sudden sense of majesty and calm beauty. There were very few visitors, the pandemic keeping tourists away.

Paestum was founded by Achaean colonists from Sybaris (on the South Italian coast near Taranto) whose taste for high living gave us the word “sybarite”, in about 600 BCE. Sybaris and Paestum are part of the Magna Grecia (Greek colonial settlements in Italy). Paestum lies on the coast south of Salerno.[1]

The Greek colonists called it Poseidonia, after the sea-god Poseidon (Neptune for the Romans). The Romans renamed it Paestum when they took over the settlement in 273 BCE. After the fall of Rome, the site sank into decline and then oblivion until the mid 18th century. The rediscovery of the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum, and the construction of a new road south of Naples helped the revival of the site. In 1778, Piranesi’s etchings revealing the splendid monumental ruins began to attract intellectuals and aristocrats, and Paestum became part of the Grand Tour.

As one enters the site, at the southern end, one suddenly discovers these two temples next to each other:

The Temple of Poseidon/Neptune (built c. 450 BCE) is the most majestic and best preserved of the temples at Paestum. In the 18th century, scholars thought that it had been built in honor of the god Poseidon after which the city was named. However it seems now that it may have been dedicated to Hera, Zeus or Apollo.

This so-called Temple of Neptune (60m X 24m, / c. 65.6 x 196.8 feet) is of Doric style, massive and powerful and yet very simple and harmonious, built of local limestone called travertine (Paestum is far from any source of marble). The fluted columns are very wide, with entasis (i.e. with a slight convexity: they widen as they go down). The peristyle consists of six columns on the front and fourteen columns along the sides. In the golden September light, the color of the stone takes on a warm, subtle beige-rose tinge.

Next to it on the left stands the Basilica or Temple of Hera (54m x 25m / c. 177 x 82 feet), Paestum’s earliest construction, estimated to be around 565 BCE, of so-called archaic Doric style, i.e. at a time when Doric style was evolving. It has nine columns at the front and eighteen columns along the sides. In the 18th century archeologists named it the Basilica because some wrongly believed it to be a Roman building. The name has remained since.

Leaving the southern end of the site, we move on through extensive Roman ruins—houses and a Roman forum—along a paved Roman road to the northern end of the site where stands the Temple of Athena (built late 6th century BCE, 34m X 13m, c112 x 44 feet), also called Temple of Ceres—at some point it was thought to have been dedicated to Ceres (Roman goddess of agriculture and fertility, the Greek equivalent is Demeter). All a little confusing!

It is surrounded by six x thirteen Doric columns. Again, very simple, dignified.

The three temples are among the best preserved Ancient Greek temples. I thought they were magnificent.

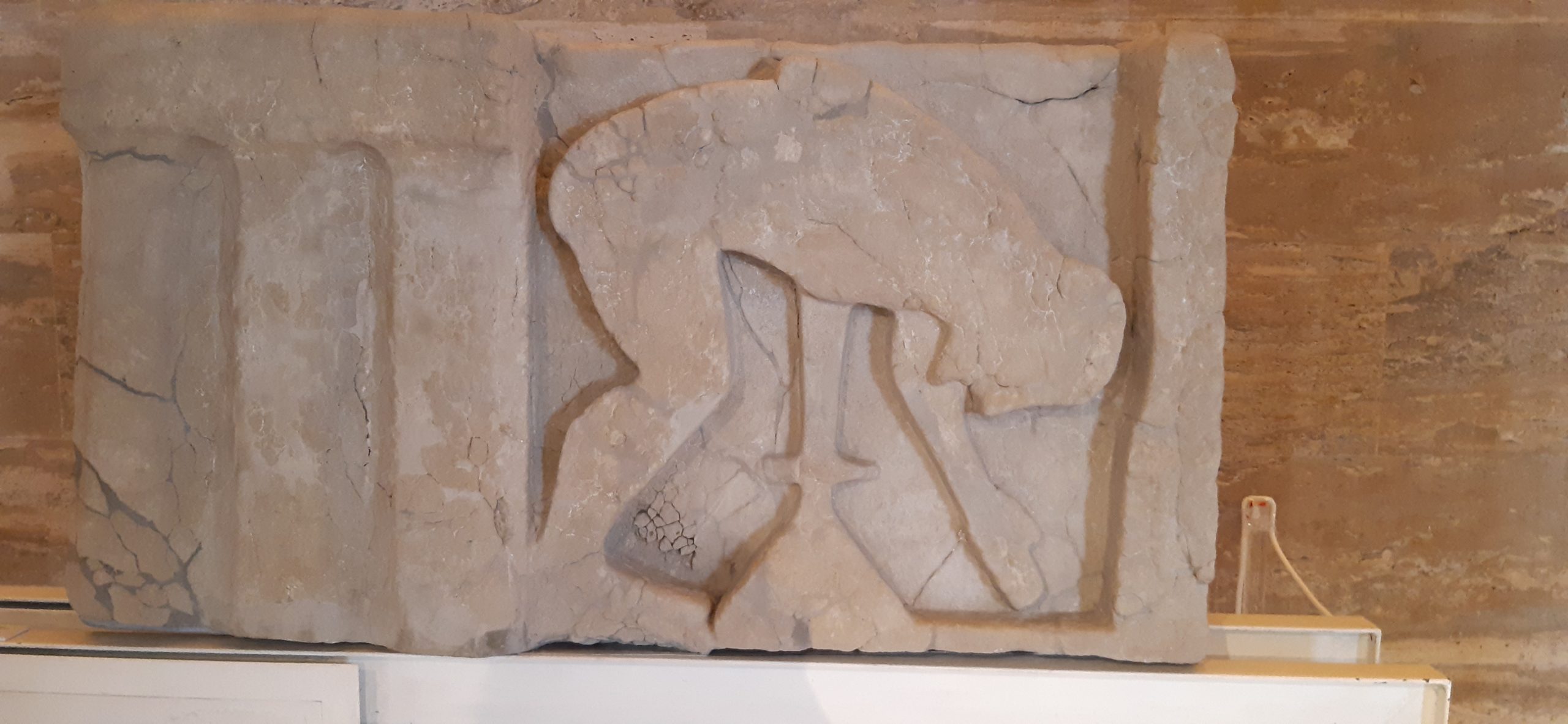

But there was more to come. Exiting the archeological site, across the road, stands the Archeological Museum. And what a discovery it was! It houses the carved metopes (relief panels) which were recovered from a former temple dedicated to Hera, the Temple of Hera Argiva, now destroyed, which lay near the mouth of the River Sele, 9 km (c. 5.6 miles) from Paestum. These metopes were discovered during excavations in the 1930s, quite a few of them being in a bad state. Dating to about 570–560 BCE, they are made of local sandstone. The scenes portrayed are taken from the world of the Greek epic, such as episodes from the Twelve Labors of Heracles, and the Trojan War. I took the photos of these metopes especially for my Iliad translation group!

Another highlight in the museum is la Tomba del tuffatore/The Tomb of the Diver, excavated in a small necropolis in 1968, about 1.5km (c. 0.9 miles) to the south of Paestum, dating back to 480/470 BCE. The decoration of the inner walls of this tomb is in the fresco technique. The lateral slabs show a scene of symposium where participants abandon themselves to the pleasure of wine and eroticism:

Whilst the main slab is decorated with the famous scene of the diver:

I stood for a long time in front of this figurative scene: I liked the elongation of the body, but then I thought, this is not a diving position; the feet, the head and the arms are not aligned in what should be a proper diving direction. And the feet are far higher than the wall from which the figure is supposedly diving!

At the same time, I thought it was beautiful; this body seemed so light and ethereal, and was somehow evocative of another body representation which I had come across before. I was searching in my mind, and suddenly I remembered: the Bull-leaper whom I saw last year in the Archaeological Museum in Herakleion, Crete.

Same elongation and tension of the limbs: seeing them side by side is quite striking.

It was getting towards the end of the afternoon by then. Domenico was waiting for me outside the museum, and even with a mask, I could detect the grin on his face: he knew I would love it. During the return journey to Naples, I sat back and let him talk and gesticulate, I just closed my eyes, and retired into my inner world of temples, fluted columns, metopes and …diving.

Credits

[1] All information regarding the history, architecture, measurements etc., of the temples was gathered with the aid of the information panels on site, of the small Arte Paestum guidebook on sale at the ticket office, and of my French Michelin Green Guide on Italy.

All photographs were taken by me.

___

Claudie Cox is a member of the Kosmos Society.