My first port of call was Iraklio/Herakleion, the capital of Crete. Truth be told, Herakleion is far from the most attractive town, with sprawling ugly suburbs. But the area around the Venetian harbor is delightful. Crete was under Venetian occupation from 1204 to 1669, and there are many remains of this, including the impressive fortress which dominates the harbor and which is still called today the Fortezza (photo 1).

The city’s top attraction is undoubtedly the Archaeological Museum (reopened in 2014 after undergoing extensive renovations), one of the greatest archaeological collections in the world, with pride of place going to the best Minoan artifacts. It is an excellent preparation for the visit to Knossos, the so-called Minos’s Palace which lies just outside the city (an easy bus ride; you can buy a combined ticket for the museum and the palace).

In the museum, finds from the Proto-Palatial period (1900–1700 BCE) include the earliest examples of Kamares ware pottery, found in the ruins of Knossos (photo 2).

The various periods are classified as follows :

- Neolithic Period (c. 7000 – c. 3200 BCE)

- Prepalatial Period (c. 3200 – 1900 BCE)

- Protopalatial Period (c. 1900 – 1700 BCE)

- Neopalatial Period (c. 1700 – 1450 BCE)

- Final Palatial Period (c. 1450 – 1380/70 BCE)

- Postpalatial Period (c. 1380/70 – c. 1050 BCE)

- Subminoan Period (c. 1050 – c. 970 BCE)

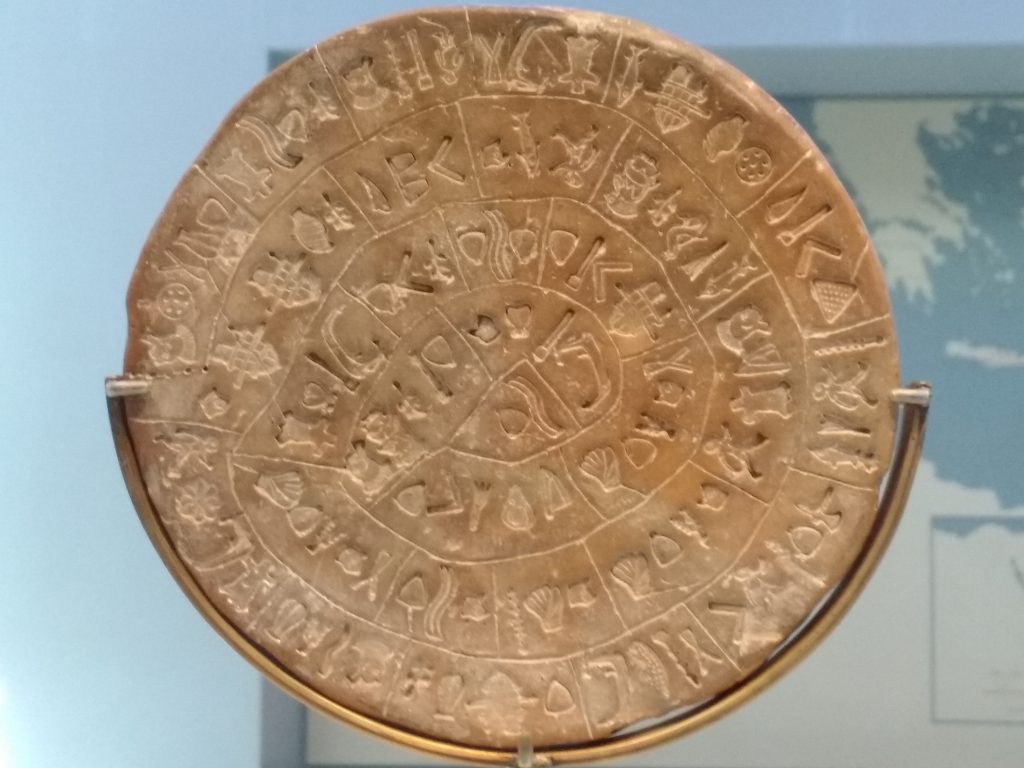

One of the finest finds is the enigmatic inscribed clay Phaistos disc (from Phaistos Palace, southern Crete), early 17th century BCE (photo 3).

It bears 45 pictorial signs, presumably representing words. Experts have still not deciphered the contents of the inscriptions.

Moving on to later periods: all the finds from the ruins of Knossos are now gathered in the museum.

I particularly liked the gracefulness of the bull-leaper, an ivory figurine from Knossos Palace 1600–1450 BCE (photo 4).

The most spectacular Minoan acrobatic sport was bull-leaping, in which young, trained athletes made a dangerous leap over the horns and back of a charging bull.

The “snake goddesses“ shown here are faience figurines, Knossos, 1650–1550 BCE (photo 5).

There is also an extensive and beautiful collection of larnakes. Clay larnakes imitate a coffin. There are 2 types of larnax: the first is in the shape of a wooden chest with a gabled lid, while the second resembles a bathtub. The deceased was placed in a fetal position. These are from Eastern Crete, 1350–1250 BCE (photos 6 and 7).

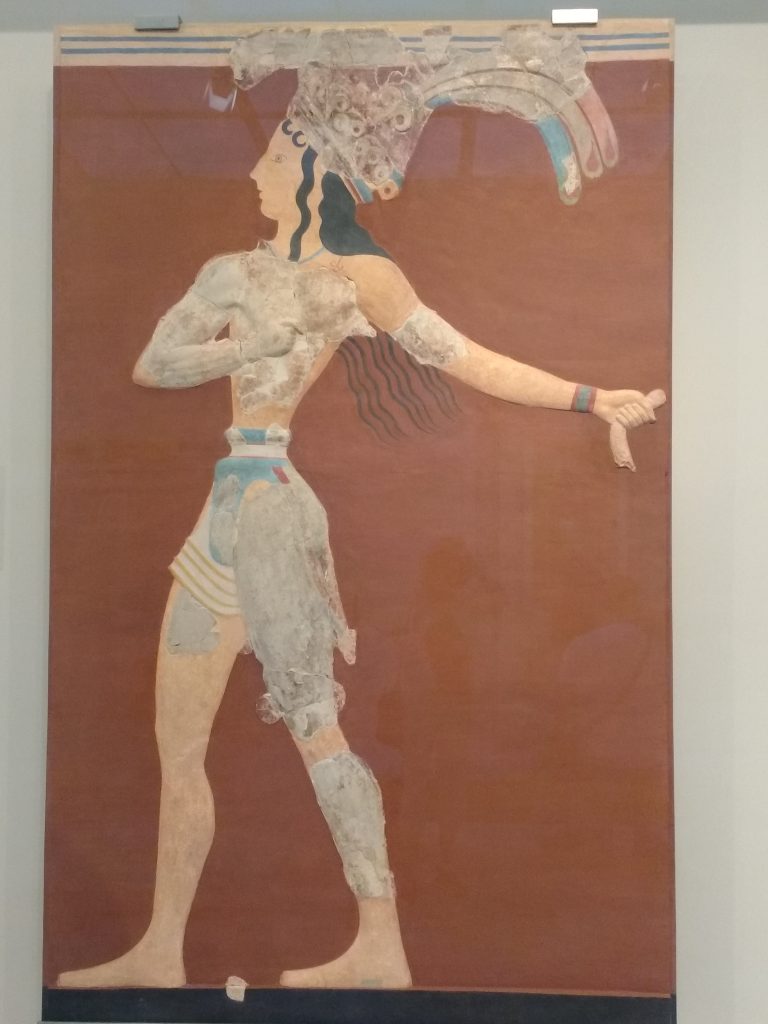

On the first floor are displayed the original Minoan wall paintings from Knossos, like this one: The Prince of the Lilies, Knossos Palace, 1600–1450 BCE (photo 8).

After such an appetizer, it was time to discover the Minoan palace at Knossos, the largest of all the palaces in Crete. According to tradition it was the seat of the wise king Minos, and many Cretans believe that Knossos was the site of the main battle between Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth beneath King Minos’s palace.

A first palace, built c. 2000 BCE, was destroyed, probably by an earthquake, about 1700 BCE. A second, larger, palace was then built on the ruins of the old one. This coincided with the golden age of the Minoan society, the Neopalatial era, from 1700 BCE. This was partially destroyed about 1450 BCE, after which the Mycenaeans established themselves at Knossos. The palace was finally destroyed about 1350 BCE by a major conflagration. The site it covered was occupied again from the late Mycenaean period until Roman time (5th century CE).

Most of what we see today are the remains of the second palace, following the long-term excavations (1900–1913 and 1922–1930) of the Englishman, Sir Arthur Evans, the then director of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, who uncovered virtually the entire palace. Evans tried a radical reconstruction using concrete on a large scale. What had been wooden Minoan columns were now made of reinforced concrete and rendered with paint. The wall paintings were restored and copies installed in their place. This has not been without arousing controversy, with many believing that the reconstructions impose Evans’s ideas and the aesthetics of his time. Others believe that the interventions were necessary for the preservation of the monument.

Some of the main outstanding features on the palace site include:

- The Central Court (photo 9)

- The Staircase (photo 10)

- The Throne Room (photo 11)

- The Queen’s Megaron or Chamber, with some of the original frescoes (photo 12)

- The North Pillar Hall (photo 13)

Other sights in Herakleion include the Harbor area, with the Venetian Fortezza well worth visiting, the excellent Historical Museum of Crete, Greek Orthodox churches, the Venetian Loggia, and a vibrant town center with a profusion of stalls and craft shops.

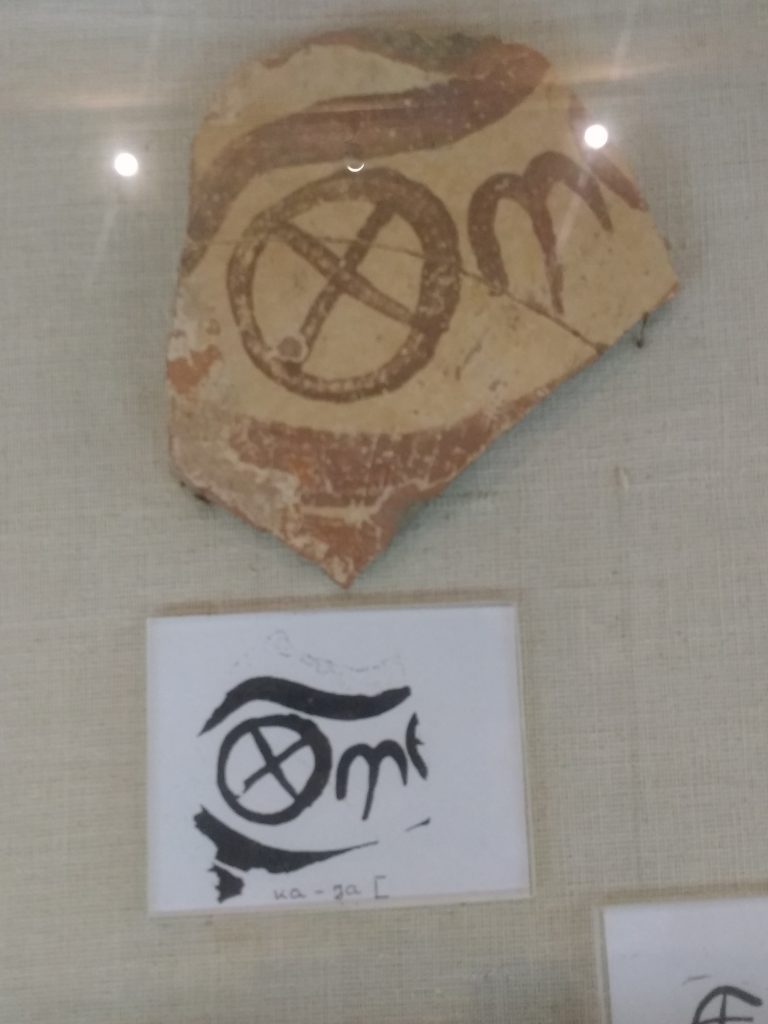

I then moved on to the west of the island, to Rethymno (another Venetian harbor and Fortezza) and Khania (Venetian harbor and arsenals). Khania also boasts an excellent archaeological museum, with examples of the Minoan Script Linear A (photo 14) and beautiful double clay vases (1420–1200 BCE) from chamber tombs in the town of Khania (photo 15).

The Linear A inscriptions are administrative records on clay, preserved when they were baked during accidentally in a fire of around 1450 BCE. The pictographs of the script have not been deciphered fully.

What I really liked was discovering the different layers of Cretan history, from the Palatial periods through to the Venetian period, still so present today, and the terrible hardships suffered by the Cretans in WW2.

And they are such warm, welcoming people!

Notes and image credits

Details of sites and artifacts, and dates, are taken from the information displays in the museums and sites visited.

Photos: Claudie Cox

___

Claudie Cox is a member of the Kosmos Society