A few weeks ago our Iliad reading/translation group translated the passage detailing the catalog of prizes for the best participants in the Funeral Games before the burial of Patroklos, Achilles’s best companion. These games evoke the Olympic Games which will take place soon in France and which will once again ignite hearts and minds. The Olympic games in Paris are going to be quite an event in July and August and will be watched worldwide. We have been following a Greek tradition for more than 2,800 years. The following sections provide information on a variety of subjects related to the origin, history, traditions, and culture of the ancient contests at Olympia.

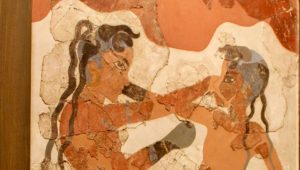

It is possible that the origin of the games can be traced to a time before the first Olympic Games of 776 BCE.[1] There is evidence that there were games and competitions in the Mycenaean era (1600 to 1100 BCE). Vase paintings dating from this time show athletes competing. Even at an earlier date, Minoan period (3000-1100 BCE) frescoes indicate some tradition of athletic contests, like boxing, wrestling and chariot races.[2]

Some ancient literature, like Hesiod’s Theogony, recount athletic competitions. Hesiod writes:

Good is she (Hecate) also when men contend at the games, for there too the goddess is with them and profits them: and he who by might and strength gets the victory wins the rich prize easily with joy, and brings glory to his parents.[3]

Homer’s epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey, also have sections devoted to athletic competitions. Most of Book XXIII in the Iliad is taken up with Funeral Games in honor of Patroklos. These games are part of a traditional burial, done according to ancient custom; they take place after the pyre has burned down and the bones of the honored dead are placed in an urn.

In Book VIII of the Odyssey, Alcinous, the King of the Phaeacians, hosts a feast in honor of Odysseus. After the feast, athletic contests were held in the hopes that, upon returning home, Odysseus will be able to tell his friends of the athletic prowess of the Phaeacians. Nicholas Richardson, in his major commentary on the Iliad, wrote:

The games in honour of Patroklos consist of eight contests. By far the longest episode is the first, the chariot race. It is followed by boxing, wrestling, running, armed combat, weight throwing, archery, and spear throwing. … In the Phaeacian games for Odysseus, in the Odyssey, the five events are running, wrestling, jumping, discus-throwing, and boxing.[4]

In the Odyssey, Homer describes the scene when Alcinous took note of Odysseus; he had hidden his face in his cloak to hide his tears upon listening to the bard, Demodocus, sing the story of Troy.

… but Alcinous alone marked him and took heed, [95] for he sat by him, and heard him groaning heavily. And straightway he spoke among the Phaeacians, lovers of the oar: “Hear me, ye leaders and counsellors of the Phaeacians, already have we satisfied our hearts with the equal banquet and with the lyre, which is the companion of the rich feast. [100] But now let us go forth, and make trial of all manner of games, that yon stranger may tell his friends, when he returns home, how far we excel other men in boxing and wrestling and leaping and in speed of foot.” So saying, he led the way, and they followed him. [105][5]

At the time of the Trojan War (c. 1250-1100 BCE), there were no Panhellenic athletic competitions held in Olympia, the sanctuary which gave its name to the Olympic Games.[6] However, several hundred years later, we have a record of an event which may be the first Olympic game, dated by modern calculations to 776 BC. According to Pausanias, Olympia is the place where the Olympic games began. The first event was a foot race.

…when the unbroken tradition of the Olympiads began there was first the foot-race, and Coroebus an Elean was the victor. There is no statue of Coroebus at Olympia, but his grave is on the borders of Elis. Afterwards, at the fourteenth Festival, the double foot-race was added: Hypenus of Pisa won the prize of wild olive in the double race, and at the next Festival Acanthus of Lacedaemon won in the long course.[7]

The sacred precinct of Olympia was contained within the borders of Elis, an independent district in ancient Greece. Hippias of Elis was the first to calculate the date of the first Olympic contest which occurred approximately 400 years before his time.[8] As there were no written records, his method produced at best an approximation. He made use of a list of Spartan kings from that time to his and assigned a fixed number of years to each intervening generation. It is impossible to know the exact year of the first Olympic event.

There were Panhellenic games in three other ancient cities: Nemea, Delphi and Corinth. Because of its location on an isthmus, the games in Corinth are known as the Isthmian games. Through Pindar’s poetry we know more about the winners and the prizes in these four most important places. However, there were local games held throughout ancient Greece.

In addition to information on the historical origins of the games, Pausanias gives a very detailed description of the mythological origin of the games.

These things then are as I have described them. As for the Olympic Games, the most learned antiquaries of Elis say that Kronos was the first king in the sky [ouranos] and that in his honor, a temple was built in Olympia by the men of that age, who were named the Golden Generation. When Zeus was born, Rhea entrusted the guardianship of her son to the Dactyls of Ida, who are the same as those called Kouretes. They came from Cretan Ida-Hēraklēs, Paionaios, Epimedes, Iasios and Idas.

Hēraklēs, being the eldest, matched his brothers, as a game, in a running race, and garlanded the winner with a branch of wild olive, of which they had such a copious supply that they slept on heaps of its leaves while still green. It is said to have been introduced into Greece by Hēraklēs from the land of the Hyperboreans, men living beyond the home of the North Wind.

Hēraklēs of Ida, therefore, has the reputation of being the first to have held, on the occasion I mentioned, the Games, and to have called them Olympic. So he established the custom of holding them every fifth year[9], because he and his brothers were five in number.

Now, some say that Zeus wrestled here with Kronos himself for the throne while others say that he held the Games in honor of his victory over Kronos. The record of victors includes Apollo, who outran Hermes and beat Ares at boxing. It is for this reason, they say, that the Pythian aulos song is played while the competitors in the pentathlon are jumping; for the aulos song is sacred to Apollo, and Apollo won Olympic victories.[10]

Leaping is one of the contests mentioned by Alcinous in the Odyssey and it evokes the leaping athlete found in Crete. However, competitive bull leaping was not part of the ancient games at Olympia. Instead, athletes competed in the long jump to see which contestant could travel the longest distance from the time his feet left the ground until he landed. Then, as now, the jumper landed in a sand pit to help cushion fall.

The long jump was introduced at Olympia in 708 BCE[11] as part of the pentathlon, a group of five different contests. According to Donald Kyle, we are not certain how the pentathlon was conducted at the ancient games in Olympia. Several scholars have proposed different theories. All agree that there was only a first place winner for each event and only one winner for the entire set. The current scholarship indicates that the pentathlon competition was conducted in rounds. The first round consisted of only three contests. Besides the long jump, the first round included the javelin throw and the discus throw. Each participant did his best in all three events. The winner would have to win all three to be declared the overall winner. However, if no single victor emerged in this round, a foot race was added in which all victors, but not all competitors, would compete. If one contestant now had three victories, he was the winner of the event. Wrestling was the final event and was conducted as a one-on-one elimination round. The victor who first accumulated three wins was the victor of the pentathlon.[12]

In addition to the pentathlon, other contests were held at Olympia. There were three kinds of equestrian contests: two-horse chariot races, four-horse chariot races, and horse riding races. The winners of the chariot races were not the charioteers, but rather the horses and their owners. There were four running events of different lengths measured by a predetermined number of laps in the stadium. In one race the athletes wore armor and carried a shield. Besides wrestling, the other one-on-one fighting contests were boxing and the pankration. A boxer wrapped his hands and wrists in leather and tried to knock out his opponent. The pankration, a combination of wrestling and boxing, was a no holds barred sport in which the only things forbidden were biting and gouging the eyes or nose of an opponent.[13]

Chariot racing was the only way women could participate in the Games. In Homer’s Odyssey, Nausicaa drove a mule cart down to the river where she played ball games and swam with her companions while doing laundry.[14]

However, in the ancient Olympics, women were not the charioteers but instead entered their team of horses in the races. In 396 BC, Cynisca, a Spartan princess and daughter of the Eurypontid king Archidamus II, entered the team she trained in the four-horse chariot race where she won her event. [15] She won again in 392 BCE.

Based on archaeological evidence such as the locations of her dedications and hero-cult, Cynisca’s win at the Olympics inspired women across the Greek world. After Cynisca’s victory, several other Greek women went on to achieve varying levels of success in the sport of chariot racing, including Euryleonis, Belistiche, Zeuxo, Encrateia and Hermione, Timareta, Theodota, and Cassia. However, according to Pausanias,[16] none of these women gained greater recognition for their victories than Cynisca.

The prizes offered to participants by Achilles at the time of Homer or during the Trojan War were more grand than the simple medals given to the first, second and third place winners now. Certain prizes mentioned in Homer may shock us today because our values have changed since then. They are of interest because they show us what had value at that time. For example, this is what Achilles awarded as prizes to all the victorious horsemen. And the fact that there were five prizes, one for each participant, stresses the value put on participation and which prizes had the highest value.

He (Achilles) brought from the ships prizes, cauldrons and tripods and horses and mules and the strong heads of oxen, and well-girdled women and gray iron. First for the swift horsemen, he set as noble prizes, a skillful-at-work woman to lead away and also a tripod with ears holding twenty-two measures, for the first, but for the second a six year old mare unbroken, swollen with an unborn mule, then for the third prize he set a beautiful unfired cauldron, with a capacity of four measures fresh from the maker’s hand, and for the fourth he set two talents of gold, and for the fifth he set a double base urn untouched by fire.[17]

There were no prizes for the winners of the games in Phaeacia, but the Phaeacians were generous and gave many wondrous gifts to Odysseus when he left their island, as well as the most welcome gift of all for Odysseus, passage home on one of their sailing ships.

During the ancient Olympic games, and other major athletic competitions elsewhere in ancient Greece, there was only one winner for each event and, as noted above, one overall winner for the pentathlon. The victor received only a wreath or a crown woven from leaves. In Olympia, this was a wreath made from wild olive leaves. Immediately after the event, the winner also received a red woolen ribbon, the taenia, which was tied around his head and hands. He was then presented with a palm frond as the spectators applauded and threw him flowers.[18]

All the victors were honored in an official prize ceremony which took place on the last day of the Games in the raised hall in the Temple of Zeus. In a loud voice, the herald announced the name of the Olympic victor, his father and his city. Then a Hellanodikos (official judge of the games) placed a crown made of an olive branch, the kotinos, on the winner’s head.[19]

However, other rewards awaited the victor in his hometown where he would be welcomed as a hero and receive lifelong benefits. He might receive an amphorae of olive oil, a bronze tripod or shield or a silver cup. Some city-states erected his statue in the agora (town square). A wealthy benefactor might commission a poet to write an ode about his victory as a special tribute. Some victors took on a political role. The Greeks believed that victors were chosen by the gods. It was thought that he brought honor to his entire community.[20]

The Hellanodikai (Ἑλλανοδίκαι), whose literal meaning is “Judges of the Greeks,” were citizens of Elis whose duties included judging the ancient Olympic Games and enforcing the code of conduct on the competitors. Rule breakers among either the participants or the spectators were punished with flogging and fines. The Hellanodikai also supervised the ten month training period prior to the games and selected the athletes who were qualified to compete. They were able to disqualify athletes whose city-state violated the Sacred Truce. And, as stated above, the Hellanodikai awarded the prizes to the victors at the final ceremonies.[21]

Contestants in the ancient games competed nude with the exception of charioteers. This is well attested by numerous vase paintings of nude runners, boxers, and wrestlers. The reason for this custom is also debated. Heather Reid and Georgios Mouratidis, in “Naked Virtue: Ancient Athletic Nudity and the Olympic Ethos of Arete,” put forward three possible explanations: performance enhancement, the safety of the athlete, and a widespread belief among the Greeks that the naked body symbolized virtue and was a divinely inspired form of beauty, that is, the ultimate expression of arete or excellence. [22] Perhaps this also guaranteed that all contestants were male.

Ancient authors support two of these explanations for competing nude. Pausanias tells us that Orsippus of Megara won his race after losing his loincloth. However, he goes on to say that Orsippus intentionally “let the girdle slip off him realizing that a naked man can run more easily than one girt.”[23]

Other sources “attribute the introduction of athletic nudity to an accident which occurred in Athens during the archonship of Hippomenes, in the 14th or 15th Olympiad (724 or 720); a runner fell and was killed when his loin-cloth either slipped or otherwise interfered with his performance, and it was decreed that running should henceforward be in the nude.”[24]

Reid and Mouratidis argue at length for the third explanation, that is on the basis of the cultural values of the ancient Greeks. Gods were often portrayed nude, displaying their perfect form. By competing unclothed the athletes seek to imitate and emulate the divine form of their gods.[25]

Another interesting Olympic tradition mentioned by Pausaniasis was the truce maintained between all Greek cities for the duration of the Olympic games.

…The discus of Iphitos has inscribed upon it the truce which the Eleians proclaim at the Olympic festivals; the inscription is not written in a straight line, but the letters run in a circle round the discus.[26]

A truce (in Greek, ekecheiria, which literally means “holding hands”) was necessary in order to ensure the safety of the athletes and the spectators who came from all over Greece to participate in the event. For the duration of the games, in addition to the suspension of warfare, even legal disputes and the conduct of capital punishments were banned. Armies were forbidden entry to Elis and from threatening the games. There was no enforcement mechanism for the truce; clearly, all Greeks wanted the games to proceed peacefully.

One notable violation of the Olympic truce was reported by the historian Thucydides. He relates that the Lacedaemonians were accused of attacking a fortress in Lepreum, a town in Elis, during the truce. The Lacedaemonians disputed the claim, claiming that their attack preceded the start of the games. Nevertheless, Lacedaemonian contenders were not allowed to participate in the games until they paid the Eleans a fine, established by law, of two thousand minae, two for each soldier involved in the attack.[27]

By the archaic period (700-480 BCE), the Olympic Festival held at Olympia was primarily a Panhellenic religious festival in honor of Olympian Zeus where athletic competitions were also held. According to Sarah C. Murray, Professor of Classics at the University of Toronto, “… the games and the sacred rites of the festivals where they took place were inextricably linked.”[28]

In a similar way, the annual Dionysia in Athens, a festival of theatrical competition, was held in honor of the god Dionysus. The conduct of the games was interwoven with rituals including sacrifices, oaths, processions and prayers. This was not only true at the Olympics, but at all the Panhellenic games and at more local competitions as well. Each locale had its own supreme deity who was honored by the athletes.[29]

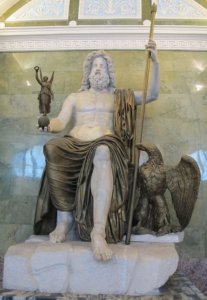

At Olympia one of the first things that competitors did upon entering the sanctuary was to swear by Zeus to uphold the rules of the games (Pausanias5.24.9). When lots were drawn to determine starting positions, they were drawn from a vessel that was consecrated to Zeus, and each competitor took his turn after reciting a prayer to the god (Lucian Hermotimos 40).[30] In the image below, the centrality of the Temple of Zeus to the athletic competitions held at Olympia is clear.

Greeks also believed that winners and losers were chosen by the presiding deity and winning was seen as a sign of divine favor. Victors were sometimes elevated to hero status and worshiped as cult figures.[31]

Lucian of Samosata describes a dialog between Solon and Anacharsis[32] in which Solon says:

…go to the competitions and see that great crowd of people gathering to look at such spectacles, see the theaters that will hold thousands filling up, see the contestants applauded, and see the contestant who wins being viewed as equal to the gods.[33]

Gregory Nagy indicates that Olympic victors are associated with myth and rituals just as the heroes who died valiantly were honored in myth and worshiped in ancient Greece through cultic rituals. We have seen above that Hesiod also thought that victorious athletes also earned glory for their victories. Nagy proposes an analogy between the cultic worship of immortalized heroes who have fallen in battle and cultic worship of Heracles after his death and apotheosis and his founding of the games at Olympia.

This myth about Hēraklēs as the founder of the Olympics at Olympia is a perfect illustration of a fundamental connection between the labors of heroes and the competitions of athletes at athletic events like the Olympics. The hero’s labor and the athlete’s competition are the “same thing,” from the standpoint of ancient Greek concepts of the hero (H24H Hour 8b). That is why the Greek word for the hero’s labor and for the athlete’s competition is the same: āthlos.[34]

As a further example of ritual at Olympia, Pausanias describes rites conducted by the women of Elis at Olympia associated with Achilles, the hero of the Iliad, who had a cenotaph there “raised to him because of an oracle.”

When the festival [panēguris] [of the Olympics] begins, on an appointed day, at the time when the sun, in the course-of-its-[daily]-run [dromos], is sinking toward the west, the women of Elis have-the-custom [nomizein] of doing-ritual [drân], in various ways, for the purpose of giving honor [tīmē] to Achilles, especially by way of bewailing [koptesthai] him.[35]

Strabo disputes the mythological origins of the games cited by Pausanias.[36] According to him the Aetolians with the Eleians invented the games and were the first to celebrate the first Olympiads. Even ancient authors did not agree about the earliest history of the games.[37]

With the rise of Christianity, the religious nature of athletic festivals made them a target for Christian evangelists. Scholars have discredited the view that Theodosius I abolished the games at Olympia. Theodosius I banned what had been the official pagan religion of the Roman state. As a result, traditional sacrifices and the worship of Zeus at his temple in the center of the sacred site at Olympia were officially prohibited.[38]

However, it is unlikely that this edict took immediate effect. Becoming closer to the gods, to be the very best, had for centuries been an essential part of the ancient games. Without this cultural underpinning and without Imperial funding, the games gradually came to an end. A significant factor in the decline of participation and attendance at the ancient athletic games may have been the increasing popularity of the circus.[39]

The tradition of athletic competition at Olympia continued for over a thousand years, from the archaic age until sometime in the century or so after 393 CE. The last reported victor at the Olympic games was Zopyros, a boxer from Athens, in A.D. 385.[40]

Competition was central to the culture of ancient Greece. They competed in all aspects of life whether in the field of politics, sport, drama, music, poetry, warfare, and in courtrooms, as individuals and collectively against members of other city-states. Ancient Greeks also enjoyed the role of spectator at these competitions. The word agon (ἀγών), associated with athletic contests, also includes the notion of a gathering to watch the competition.[41]

Panhellenic festivals and local festivals were popular activities where audiences could vicariously enjoy watching the best compete against each other. A great amount of effort was expended by the competitors in training and preparing for the crucial event. This was especially true for athletic contests. Victors were celebrated in poetry and song, in sculpture and inscriptions. Surviving inscriptions and literary sources list the names of about eight hundred ancient Olympic champions.[42]

According to Gregory Nagy, “The Iliad was venerated by the ancient Greeks themselves as the cornerstone of their civilization.[43] On two occasions, the Iliad presents a scene in which a character relates how a father advises his son to “always be the best and be better than the rest.” The words Homer used were: αἰὲν ἀριστεύειν καὶ ὑπείροχον ἔμμεναι ἄλλων.[44]

The first occurrence takes place when Diomedes meets Glaucus during a battle. They exchange lineages. Glauscus tells Diomedes:

Hippolochos begot me, and I claim that he is my father; he sent me to Troy, and urged upon me repeated injunctions, to be always among the bravest, and hold my head above others, not shaming the generation of my fathers, who were the greatest men in Ephyre and again in wide Lykia.[45]

The second occurrence takes place during the embassy scene when Phoenix reminds Achilles of how he had helped to raise him.

And Peleus the aged was telling his own son, Achilleus, to be always best in battle and pre-eminent beyond all others.[46]

Much of the Iliad is devoted to Greek warriors who follow this advice whether in public speaking, in battle, or in athletic games. It presents many scenes of one-on-one competition, not only between men, but also between the gods. The Iliad elevates martial competition in dramatic scenes in which an individual hero triumphs over other combatants by virtue of his excellence and courage. These scenes depict the aristeia of the hero, literally his finest moments. The gods often join in the fray to help a favored warrior or to fight amongst each other. The gods approved of the competition and chose the winners and losers. There are displays of speech contests, between Achilles and Agmemnon in front of the assembled Greek army, between Achilles and the members of the embassy (Odysseus, Phoenix, and Ajax), and in the trial scene depicted on the shield of Achilles. And, most relevant here, in athletic competitions during the funeral games for Patroclus.

Striving to be the best is expressed by the Greek word arete (ἀρετή) meaning excellence. For Plato, this was moral excellence. It is connected with aristos, another term for excellence but also meaning superior, the best. The pursuit of athletic excellence, to be the best, to win a competition is what Olympic athletes strive for. To watch a flawless athletic performance brings the spectators joy.

What does it mean when we say of an action, an artistic work, or some flawless athletic maneuver, that it is excellent? … We perform an action with excellence and say, “perfect!” In the moment of excellence, something transcends the mundane and touches the Ideal.[47]

Most of the ancient contests are still part of the Olympic Games of our times. Alcinous’ words above show the competitive spirit of the people living around the Aegean Sea in ancient times: go and tell the world that we are the best athletes, which is exactly what athletes today want to do. In ancient Olympia, spectators and athletes from all over the Greek speaking world gathered to participate in the games. The athletes came to win glory for themselves and for their home cities. Today, at the modern games, we do the same thing with the difference that athletes and spectators come from around the entire globe and the athletes win glory for themselves and for their countries.

As I wrote in another post after my visit to Olympia in 2017, the sacred site is filled with trees and flowers, the birds sing a melodious song; the Muses seem to welcome us. Olympia is a sanctuary of Zeus near the river Alpheus (Alpheios), and the river Cladeus (Kladeos). A temple (completed around 456 BCE) and a magnificent statue (one of the seven wonders of the world) were built to honor Zeus. The statue of Zeus built by Pheidias, who had his workshop at Olympia, is no longer in Olympia, but the remains of the temple still exist. There is another temple in Olympia, The Temple of Hera which is older than the Temple of Zeus. This is where the lighting of the Olympic Torch takes place now.

Feel free to share your thoughts, add more examples of rituals, or pictures, and join us in the discussion.

Notes

1 Stuttard 2012, 9.

2 Yalouris 1982, 13-37.

3 Hesiod 1914, 450-452.

4 Richardson 1993, 201-202.

5 Homer, Odyssey, 8.94-105, 1918.

6 Gregory Nagy, Section II-G4, 2019.

7 Pausanias 5.8.6, Translated by W.H.S. Jones, 1918.

8 Christesen 2009, 161.

9 The games were actually four years apart. However, the Greekscustomarily counted a span of years inclusively, that is the range included the years for two consecutive games.

10 Pausanias 5.7-5.10, Translated by Gregory Nagy, 2018.

11 Kyle 1990, 299.

12 Kyle 1990, 302.

13 Riley 2022, 1.

14 Homer Odyssey, 6.85-110, 1919.

15 Mills 1994, 8-9

16 Pausanias, 3.8.1-3, Translated by W.H.S. Jones, 1918.

17 Homer, Iliad 23.262-273. Translation by the Kosmos Society Iliad Study Group, 2024.

18 International Olympic Committee 2022. 3.

19 International Olympic Committee 2022. 3

20 International Olympic Committee 2013. 11.

21 David G. Romano 2007, 95-113.

22 Heather Reid & Georgios Moutardis 2020, 30.

23 Pausanias, 1.44.1, Translation by W.H.S. Jones, 1918.

24 Thomas H. Nielsen 2007, 25.

25 Heather Reid & Georgios Moutardis 2020, 32-33.

26 Heather Reid & Georgios Moutardis 2020, 20.

27 Perseus Project 2004.

28 Murray 2014, 313.

29 Murray 2014, 314.

30 Murray 2014, 314.

31 Murray 2014, 309.

32 A Scythian prince and philosopher of uncertain historicity who lived in the 6th century BCE.

33 Lucian, Anacharsis, 10.3, 1925 (Reprint1961).

34 Gregory Nagy, The Apotheosis of Hēraklēs on Olympus and the Mythological Origins of the Olympics Part II, 2019.

35 Pausanias 6.23.3, translation by Gregory Nagy, 2018.

36 Pausanias 6.25.3, translation by Gregory Nagy, 2018.

37 Strabo 8.3.30,Geography, 1903.

38 Sofie Remijsen 2015, 187-191.

39 Sofie Remijsen 2015, 170-171.

40 Sofie Remijsen 2015, 174.

41 Wang Daqing 2007, 6805.

42 Alexis Belis 23 July 2021.

43 Gregory Nagy, Heroes and the Homeric Iliad, 2013.

44 Joel Christensen 2016.

45 Homer. Iliad 6.206-208, Translated by Richmond Lattimore, 1951.

46 Homer. Iliad 11.783-789, Translated by Richmond Lattimore, 1951.

47 John Uebersax, 2012.

Bibliography

M. Andronicos, J., Kakridis, J., Sakellarakis, N., Yalouris, et al. The Olympic Games in Ancient Greece. Yalouris, Nicolaos (ed.). Athens: Ekdotike Athenon.

Belis, Alexis, “The Ancient Olympics and Other Athletic Games, The Met: Perspectives-Sports. 23 July 2021. Digital version on TheMet website. Accessed 28 June 2024.

www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/articles/2021/7/ancient-greek-olympic-games

Christensen, Joel. Be the Best: Wonderful Terrible Advice. 20 August 2016. Digital version on the Sententiae Antiquae website. Accessed 29 June 2024.

sententiaeantiquae.com/2016/08/20/be-the-best-wonderful-terrible-advice/

Christesen, Paul.Whence 776? The Origin of the Date for the First Olympiad. The International Journal of the History of Sport Vol. 26, No. 2, February 2009. 161-182. Digital version on the Academia.edu website. Accessed 26 June 2024.

www.academia.edu/5242010/Whence_776_The_Origin_of_the_Date_for_the_First_Olympiad.

Daqing, Wang. “On the Ancient Greek ἀγών,” in Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 2: Selected Papers of Beijing Forum 2007 . Netherlands: Elsevier Ltd, 2010, 6805-6812.

Digital version on the Science Direct website. Accessed 29 June 2024.

www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042810011651?ref=pdf_download&fr=RR-2&rr=89d292a6fc432aa9

Hesiod, Theogony. Translated by Hugh Gerard Evelyn-White.

Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 1914.

Digital version on the Theoi website. Accessed 26 June 2024.

www.theoi.com/Text/HesiodTheogony.html

Homer. The Iliad. Translated by Richard Lattimore.

Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press, 1951.

Digital version on the InternetArchive website. Accessed on 29 June 2024.

archive.org/details/the-iliad-homer-lattimore/mode/2up

Homer. The Odyssey. Translated by A.T. Murray. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1919.

Digital version on Perseus Digital Library website. Accessed 26 June 2024.

www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0136%3Abook%3D8%3Acard%3D83

International Olympic Committee.

“Rewards,”Factsheet: The Olympic Games of Antiquity. 26 September 2022.

Digital version on the IOC website. Accessed 26 June 2024.

stillmed.olympics.com/media/Documents/Olympic-Games/Factsheets/The-Olympic-Games-of-the-Antiquity.pdf

Kyle, Donald. “Winning and Watching the Greek Pentathlon,”

Journal of Sport History, Vol. 17, No. 3, Winter, 1990. 291-305.

Digital version on the JSTOR website. Accessed 27 June 2024.

www.jstor.org/stable/43609192

Lucian VolumeI V. Anacharsis. Translated by A. M. Harmon.

London: William Heinemann Ltd, 1925.(Reprint1961). 11.

Digital version on the InternetArchive website. Accessed 28 June 2024.

archive.org/details/L162LucianIVAnacharsisMenippusAlexander/page/138/mode/2up?view=theater

Mills, Brett D., Women of Ancient Greece: Participating in Sport?

(ED370951). ERIC, 1994. 8-9.

Digital version on the ERIC website. Accessed 11 July 2024.

files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED370951.pdf

Murray, Sarah C. “The Role of Religion in Greek Sport,” in A Companion to Sport and Spectacle in Greek and Roman Antiquity, First Edition. Paul Christesen & Donald G. Kyle (eds). Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014.

Digital version on the Knowledge Commons website. Accessed 28 June 2024.

hcommons.org/deposits/objects/hc:29966/datastreams/CONTENT/content

Nagy, Gregory. “Heroes and the Homeric Iliad,” Greek and Roman Myths of Heroes.

Digital version on University of Houston website, Classics 3307, 2013. Accessed 29 June 2024. www.uh.edu/~cldue/texts/introductiontohomer.html

Nagy, Gregory. “Olympus as Mountain and Olympia as Venue for the Olympics: A Question about the Naming of These Places,” Classical Inquiries, Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, 6 July 2019.

Digital version on the Classical Inquiries website. Accessed 27 June 2024.

classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/olympus-as-mountain-and-olympia-as-venue-for-the-olympics-a-question-about-the-naming-of-these-places/

Nagy, Gregory. “The apotheosis of Hēraklēs on Olympus and the mythological origins of the Olympics,” Classical Inquires. Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, 12 July 2019.

Digital version on the ClassicalInquiries website. Accessed 28 June 2024.

classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-apotheosis-of-herakles-on-olympus-and-the-mythological-origins-of-the-olympics/

Nielsen, Thomas H. “Hellenic Athletic Nudity,” Olympia & the Classical Hellenic City-State Culture. København: Hans Reitzels Forlag, 2007. 22-28.

Digital version on The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters website. Accessed 29 June 2024.

www.royalacademy.dk/Publications/Low/2083_Nielsen,%20Thomas%20Heine.pdf

Pausanius. “A Pausanias Reader in Progress: Description of Greece, Scrolls1-10.” Translated by Gregory Nagy. Classical Continuum, New Alexandria Foundation, 27 July 2018.

Digital version on the Classical Continuum website. Accessed 27 June 2024.

continuum.fas.harvard.edu/primary-source/a-pausanias-reader-in-progress-description-of-greece-scrolls-1-10/

Pausanias. The Description of Greece, Volume I: Books 1-2. Translated by W.H.S. Jones, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1918.

Digital version on the ToposText website. Accessed 27 June 2024.

topostext.org/work/213

Perseus Project. “The Olympic Truce,”

The Ancient Olympics: The Context of the Games and the Olympic Spirit. Classics Department, Tufts University. 2004.

Digital version on the Perseus Digital Library website. Accessed 27 June 2024. www.perseus.tufts.edu/Olympics/truce.html

Reid, Heather and Mouratidis, Georgios. “Naked Virtue: Ancient Athletic Nudity and the Olympic Ethos of Aretē,” Olympika. Vol. 29. 2020. 29-55.

Digital version on the Academia.edu website. Accessed 29 June 2024.

www.academia.edu/61868432/Naked_Virtue_Ancient_Athletic_Nudity_and_the_Olympic_Ethos_of_Aret%C4%93?rhid=29026866247&swp=rr-rw-wc-79051877

Remijsen, Sofie. The End of Greek Athletics in Late Antiquity. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2015. 181-197.

Richardson, Nicholas. “Book 23” in The Iliad: A Commentary, Volume VI, Kirk, Geoffrey S. (ed.). Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2012.

Riley, Patrick. “Events of the Ancient Olympic Games,” Encyclopedia Britannica, edited by Editors of the Encyclopaedia, 7 February 2022.

Digital version on the Britannica: Arts & Culture website. Accessed 29 June 2024.

www.britannica.com/story/ancient-olympic-games

Romano, David G. “Judges and Judging at the Ancient Olympic Games,”

Onward to the Olympics: Historical Perspectives on the Olympic Games. Gerald P. Schaus (ed.), Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier Press, 2007. 95-113.

Strabo, Geography, Translated by Hans C. H. Hamilton. London: G. Bell & Sons, 1903.

Digital version on the Perseus Digital Library website. Accessed 25 June 2024.

www.perseus.tufts.edu/Olympics/truce.html

Stuttard, David.Power Games: Ritual and Rivalry at the Ancient Greek Olympics.

London: British Museum Press, 2012. 9.

The Olympic Museum Educational and Cultural Services. “Winners’ Rewards,”

The Olympic Games in Antiquity 3rd edition. The Olympic Museum (ed.),Translated by the IOC Language Services. Lausanne. 2013.

Digital version on the IOC website. Accessed 26 June 2024.

stillmed.olympic.org/media/Document%20Library/OlympicOrg/Documents/Document-Set-Teachers-The-Main-Olympic-Topics/The-Olympic-Games-in-Antiquity.pdf

Uebersax, John. “Explanation of ἀρετή,”Ten Greek Philosophical Terms. 2014.

Digital version on the John Uebersax website. Accessed 29 June 2024.

www.john-uebersax.com/plato/words/arete.htm

Related topics

Image credits

Boxing boys in Thera from the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. Courtesy of Kosmos Media.

The Stadium, Olympia. Courtesy of Kosmos Media.

Bull Leaper. Photograph by Claudie Cox. Courtesy of Kosmos Media.

Roman bronze copy of Myron’s lost mid fifth century BCE Discobolus. Photograph by Matthias Kabel.

Creative CommonsAttribution-Share Alike 3.0 license, granted by Wikimedia Commons

Drawing of Cynisca of Sparta, FirstFemale Olympic Champion,

Sophie de Renneville from Biographie des femmes illustres de Rome, de la Grèce,

et du Bas-Empire. Mme. De Renneville. Paris: Chez Parmantier, Libraire, 1825.

Public Domain.

Two wrestlers in action at the Palaistra. Photograph by Gorgo. Courtesy of Kosmos Media.

Site plan of the Sanctuary at Olympia based on Pausanias’ description of Greece

Department of Classics and Ancient History, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK

Roman copy of Pheidias’ statue of Zeus from the Temple at Olympia, now in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia. Photograph by Andrew Bossi. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 license, granted by Wikimedia Commons

Sacred Olympia, Courtesy of Kosmos Media.

Online images retrieved June-July 2024.

___

Hélène and Gorgo are members of the Kosmos Society.