In part 1 we looked at divine mothers in epic. Now in part 2 we see the difficulty of being a mortal mother of a hero.

Unlike some of the examples we looked at featuring divine mothers, these sons do not rely on their mothers or ask them for help, and the mothers seem to have no control over events or their sons’ lives. But as with the divine mothers, some are caring while others act unlovingly to their sons.

At the worst extreme we see Althaea and Meleagros as recounted in the story told by Phoenix: Meleagros had killed his own mother’s brother, and she reacts very strongly:

[565] So, right next to her [= Kleopatra], he [= Meleagros] lay down, nursing his anger [kholos]—an anger that brings pains [algea] to the heart [thūmos]. 566 He was angry [kholoûsthai] about the curses [ārai] that had been made by his own mother. She [= Meleagros’s mother Althaea] had been praying to the gods, 567 making many curses [ārâsthai] in her sorrow [akhos] over the killing of her brother [by her son Meleagros]. 568 Many times did she beat the earth, nourisher of many, with her hands, 569 calling upon Hādēs and on terrifying Persephone. [570] She had gone down on her knees and was sitting there; her chest and her lap were wet with tears 571 as she prayed that they [= the gods] should consign her son to death. And she was heard by a Fury [Erinys] that roams in the mist, 572 a Fury heard her, from down below in Erebos—with a heart that cannot be assuaged.

….. 584 Many times did his sisters and his mother the queen [585] supplicate [lissesthai] him. But all the more did he say “no!”

Iliad 9.565–572, 584–585, Sourcebook[1]

For a mother to curse her own child denotes more than his being lower on her scale of affections than her brother: she is exhibiting strong hatred, arising from extreme grief.

A different form of grief has affected Antikleia, the mother of Odysseus, who has been away for so long. He encounters her in Hādēs:

Then came the spirit [psūkhē] of my dead mother [85] Antikleia, daughter to great-hearted Autolykos. I had left her alive when I set out for sacred Troy and was moved to tears when I saw her, but even so, for all my sorrow I would not let her come near the blood till I had asked my questions of Teiresias. …

I sat still where I was until my mother came up and tasted the blood. Then she knew me at once and spoke fondly to me, saying, [155] ‘My son, how did you come down to this abode of darkness while you are still alive? ….

‘Mother,’ said I, [165] ‘I was forced to come here to consult the spirit [psūkhē] of the Theban prophet Teiresias. … [170] But tell me, and tell me true, in what way did you die? Did you have a long illness, or did Artemis shooter of arrows approach and slay you with her gentle shafts? ….

[180] My mother answered, ‘….. As for my own end it was this way: the gods did not take me swiftly and painlessly in my own house, [200] nor was I attacked by any illness such as those that generally wear people out and kill them, but my longing to know what you were doing and the force of my affection for you—this it was that was the death of me.’

Then I tried to find some way [205] of embracing my mother’s spirit [psūkhē]. Thrice I sprang towards her and tried to clasp her in my arms, but each time she flitted from my embrace as it were a dream or phantom, and being touched to the quick I said to her, [210] ‘Mother, why do you not stay still when I would embrace you? If we could throw our arms around one another we might find sad comfort in the sharing of our grief [akhos] even in the house of Hādēs; does proud Persephone want to lay a still further load of grief upon me by mocking me with a phantom only?’

[215] ‘My son,’ she answered, ‘most ill-fated of all humankind, it is not Persephone, daughter of Zeus, that is beguiling you, but all people are like this when they are dead. The sinews no longer hold the flesh and bones together; [220] these perish in the fierceness of consuming fire as soon as life has left the body, and the spirit [psūkhē] flits away as though it were a dream. Now, however, go back to the light of day as soon as you can, and note all these things that you may tell them to your wife hereafter.’

Odyssey 11.84–89, 152–156, 164–165, 170–173, 180, 198–224, Sourcebook

There is clearly great affection between mother and son. We also see Antikleia as a caring foster-mother, from Eumaios’ account—at least, when he was still a child:

“Laertes is still living and prays the gods to let him depart peacefully his own house, [355] for he is terribly distressed about the absence of his son, and also about the death of his wife, which grieved him greatly and aged him more than anything else did. She came to an unhappy end through sorrow for her son: may no friend or neighbor who has dealt kindly by me [360] come to such an end as she did. As long as she was still living, though she was always grieving, I used to like seeing her and asking her how she did, for she brought me up along with her daughter Ktimene of the light robes, the youngest of her children; [365] we were boy and girl together, and she made little difference between us. When, however, we both grew up, they sent Ktimene to Samē and received a splendid dowry for her. As for me, my mistress gave me a good khiton and cloak with a pair of sandals for my feet, [370] and sent me off into the country, but she was just as fond of me as ever. This is all over now.”

Odyssey 15.353–371, Sourcebook

We also see the concern and worry of a mother with Penelope. Already grieving and anxious over her husband Odysseus, Penelope worries about Telemachus:

Then Medon, a man of spirited mind said, “I wish, Madam, that this were all; but they are plotting something much more dreadful now—may the gods frustrate their design. [700] They are going to try and murder Telemachus as he is coming home from Pylos and glorious Lacedaemon, where he has been to get news of his father.”

Then Penelope’s heart sank within her, and for a long time she was speechless; her eyes [705] filled with tears, and she could find no utterance. At last, however, she said, “Why did my son leave me? What business had he to go sailing off in fast-running ships that make long voyages over the ocean like sea-horses? [710] Does he want to die without leaving anyone behind him to keep up his name?”

Odyssey 4.696–710, Sourcebook

His journey is part of Telemachus’ emergence from childhood to adulthood, inspired by Athena, which might explain why he starts to assert his authority against his mother:

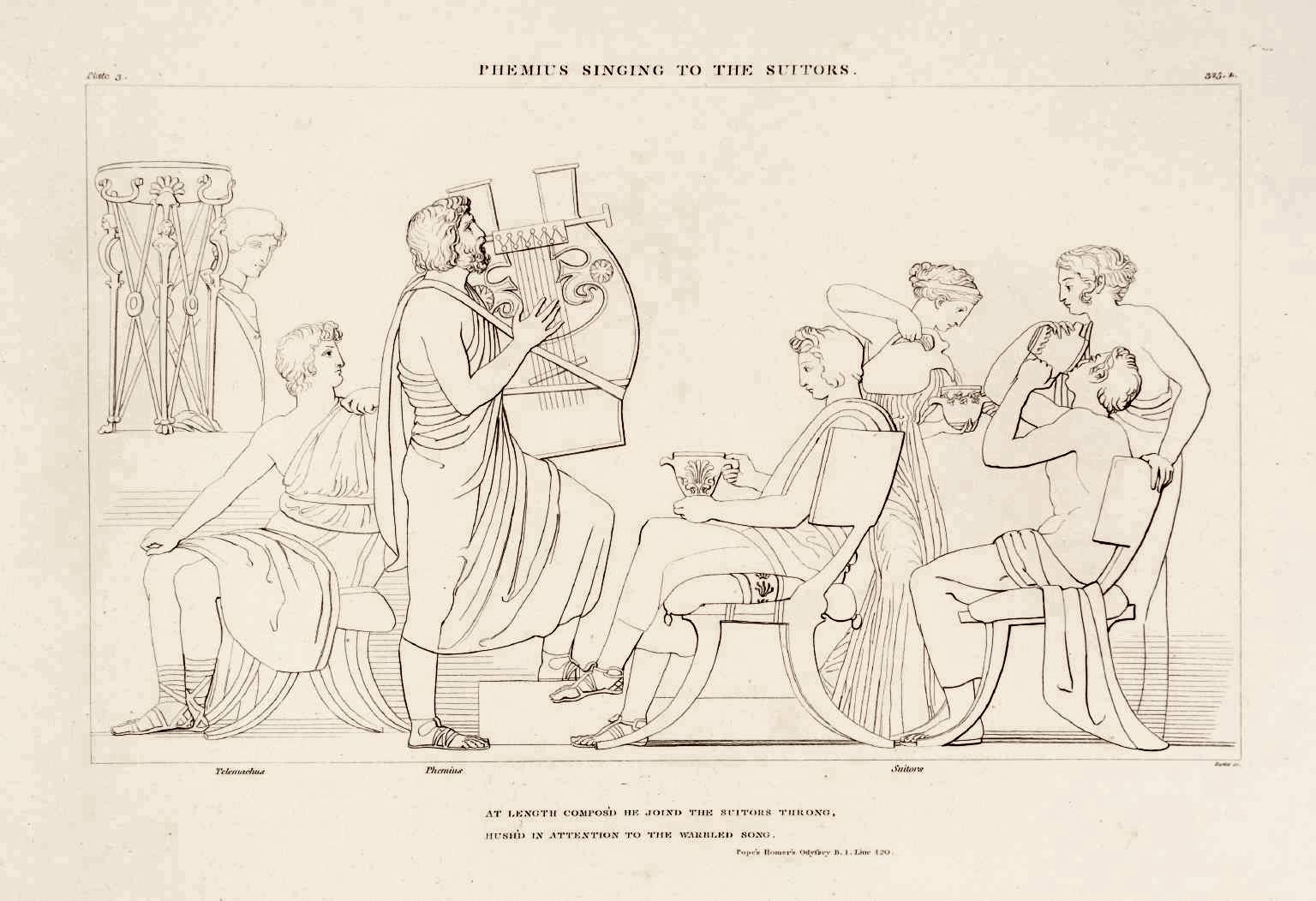

[325] The famed singer was singing for them [= the suitors],… 328 From her room upstairs, this divinely inspired song of his was understood in her mind by 329 the daughter of Ikarios, the exceptionally intelligent Penelope, [330] and she came down the lofty staircase of her palace. ….. 336 Then, shedding tears, she addressed the godlike singer:

337 “Phemios, you know many another thing that charms mortals, 338 all about the deeds of men and gods, to which singers give glory [kleeîn]. 339 Sing for them [= the suitors] some one of those songs of glory, and let them in silence [340] drink their wine. But you stop this sad song, 341 this disastrous [lugrē] song, which again and again affects my very own [philon] heart in my breast, 342 wearing it down, since an unforgettable grief [penthos alaston] comes over me, more than ever. …”

[345] “Mother,” answered the spirited Telemachus, “let the bard sing what he has a mind [noos] to; bards are not responsible [aitios] for the ills they sing of; it is Zeus, not they, who is responsible [aitios], and who sends weal or woe upon humankind according to his own good pleasure. [350] There should be no feeling of sanction [nemesis] against this one for singing the ill-fated return of the Danaans, 351 for men would most rather give glory [kleos] to that song 352 which is the newest to make the rounds among listeners. Make up your mind to it and bear it; Odysseus is not the only man who never came [355] back from Troy, but many another went down as well as he. Go, then, within the house and busy yourself with your daily duties, your loom, your distaff, and the ordering of your servants; for speech is man’s matter, and mine above all others—for it is I who am master here.”

Odyssey 1.325, 328–330, 336–342, 345–359, Sourcebook

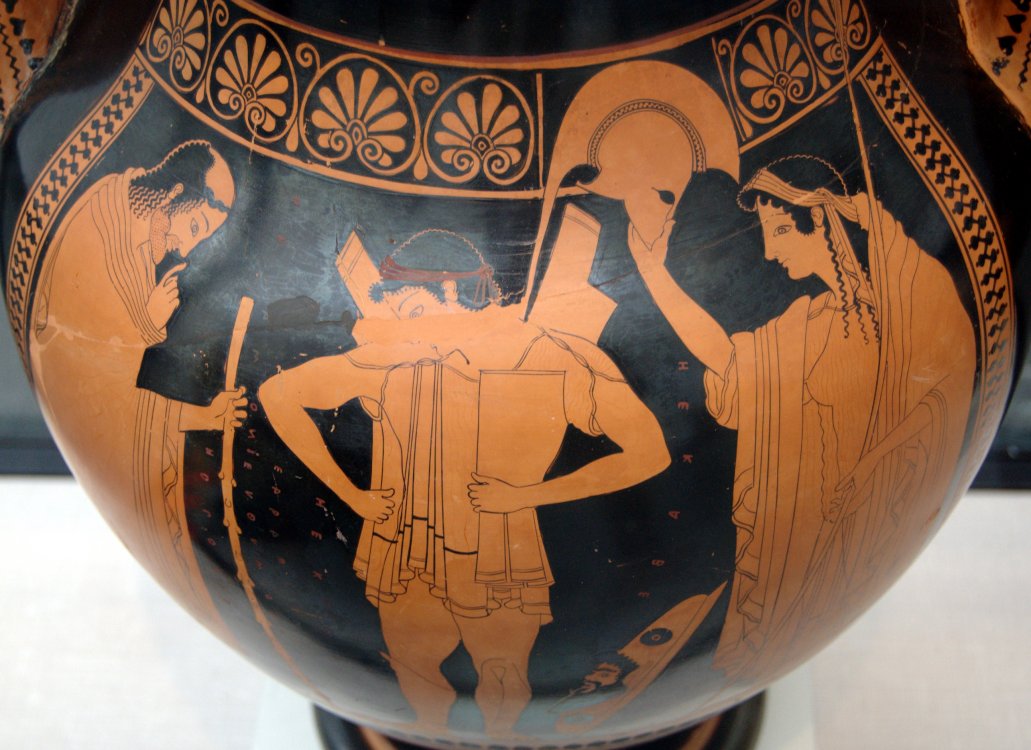

Hector, already an adult, with responsibility for protecting Troy, comes into the city in search of his mother, but does not heed her suggestions; he also tells her what she should do (albeit relaying the advice of the seer Helenos):

When Hector got there, his fond mother came up to him with Laodike, the fairest of her daughters. She took his hand within her own and said, “My son, why have you left the battle to come here? [255] Are the Achaeans, woe betide them, pressing you hard about the city that you have thought fit to come and uplift your hands to Zeus from the citadel? Wait till I can bring you wine that you may make offering to Zeus and to the other immortals, [260] and may then drink and be refreshed. Wine gives a man fresh strength when he is wearied, as you now are with fighting on behalf of your kinsmen.”

And tall Hector of the shining helmet answered, “Honored mother, bring no wine, [265] lest you unman me and I forget my strength. I dare not make a drink-offering to Zeus with unwashed hands; one who is bespattered with blood and filth may not pray to the son of Kronos. Get the matrons together, [270] and go with offerings to the temple of Athena driver of the spoil

Iliad 6.251–270, Sourcebook

Hector also pays no attention to her pleas when he is outside alone about to face Achilles:

His mother hard by wept and moaned aloud [80] as she bared her bosom and pointed to the breast which had suckled him. “Hector,” she cried, weeping bitterly the while, “Hector, my son, spurn not this breast, but have pity upon me too: if I have ever given you comfort from my own bosom, think on it now, dear son, and come within the wall to protect us from this man; [85] stand not without to meet him. Should the wretch kill you, neither I nor your richly dowered wife shall ever weep, dear offshoot of myself, over the bed on which you lie, for dogs will devour you at the ships of the Achaeans.”

Iliad 22.79–89, Sourcebook

Are there some mothers who are not mentioned, and why?

Are there actually examples of mothers who do manage to influence their sons?

Are they mostly loving relationships or are there other mothers who curse or reject their sons?

What incidents affect the relationships and do they change over time?

Join us in the forum to share further examples and to discuss mortal mothers in epic.

Notes

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2019.08.13. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

Iliad, translated by Samuel Butler, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray.

Odyssey, Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power

Image credits

Bust of Meleager Ocram (photo), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Johann Heinrich Füssli. c 1800. Teiresias, Anticleia, and Odysseus in the Underworld Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Marble stele of a woman, mid 4th century BCE, Greek. Public domain, Metropolitan Museum of Art

John Flaxman. 1805. Phemius Singing to the Suitors. Illustration to the Odyssey. Tate. Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Euthymides: Hector Arming, with Priam and Hecuba, side A of Attic red-figure amphora, c 510 BCE.

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images and online texts accessed September 2019.

___

Hélène, Janet, and Sarah are members of the Kosmos Society