In these posts we are looking at the way the relationship between mothers and sons is portrayed in Homeric epic.

In this first post we look at some divine mothers: Aphrodite, mother of Aeneas, and Thetis, mother of Achilles; Hera and Hephaistos, and the role Thetis played in caring for Hephaistos.

Because Aphrodite’s and Thetis’ sons have mortal fathers, their sons are also mortal, and will die.

Both these mothers of mortal sons seem to have strong maternal feelings, although Hera is a bit more ambiguous in her attitude to her immortal son.

Do goddesses as mothers have more power than if they were mortal mothers? Does it help? Does their own immortality shape the care they have for their children?

We first encounter Thetis when Achilles weeps by the shore of the sea:

As he spoke he wept aloud, and his mother heard him where she was sitting in the depths of the sea hard by the Old One, her father. Soon she rose up like gray mist out of the waves, [360] sat down before him as he stood weeping, caressed him with her hand, and said, “My son, why are you weeping? What is it that gives you grief [penthos]? Keep it not from me in your mind [noos], but tell me, that we may know it together.”

Iliad 1.357–363, Sourcebook[1]

Achilles tells her what has happened with Agamemnon and the Achaeans, and Briseis, and asks for her help. As a goddess she knows his ultimate fate, but still agrees to help:

Thetis wept and answered, “My son, woe is me that I should have borne and nursed you. [415] Would indeed that you had lived your span free from all sorrow at your ships, for it is all too brief; alas, that you should be at once short of life and long of sorrow above your peers: woe, therefore, was the hour in which I bore you; [420] nevertheless I will go to the snowy heights of Olympus, and tell this tale to Zeus, if he will hear our prayer: meanwhile stay where you are with your ships, nurse your anger [mēnis] against the Achaeans, and hold aloof from fight.

Iliad 1.413–422, Sourcebook

Again she comes to Achilles’ side when he is grieving over Patroklos, and promises to obtain replacement armor, from Hephaistos himself. We then find she already has a relationship with Hephaistos, having taken care of him when he was ejected from Hades.

Then she [= Kharis] called Hephaistos and said, “Hephaistos, come here, Thetis wants you”; and the far-famed lame god answered, “Then it is indeed an august and honored goddess who has come here; [395] she it was that took care of me when I was suffering from the heavy fall which I had through my cruel mother’s anger—for she would have got rid of me because I was lame. It would have gone hardly with me had not Eurynome, daughter of the ever-encircling waters of Okeanos, and Thetis, taken me to their bosom. [400] Nine years did I stay with them, and many beautiful works in bronze, brooches, spiral armlets, cups, and chains, did I make for them in their cave, with the roaring waters of Okeanos foaming as they rushed ever past it; and no one knew, neither of gods nor men, [405] save only Thetis and Eurynome who took care of me. If, then, lovely-haired Thetis has come to my house I must make her due requital for having saved me; entertain her, therefore, with all hospitality, while I put by my bellows and all my tools.”

Iliad 18.391–409, Sourcebook

Despite Hephaistos’ stormy relationship with Hera, he acts to soothe her when the gods are quarreling:

Hephaistos began to try and pacify his beloved mother Hera of the white arms. “It will be intolerable,” said he, “if you two fall to wrangling [575] and setting the gods in an uproar about a pack of mortals. If such ill counsels are to prevail, we shall have no pleasure at our banquet. Let me then advise my mother—and she must herself know that it will be better—to make friends with my dear father Zeus, lest he again scold her and disturb our feast. [580] If the Olympian Thunderer wants to hurl us all from our seats, he can do so, for he is far the strongest, so give him fair words, and he will then soon be in a good humor with us.”

As he spoke, he took a double cup of nectar, [585] and placed it in his mother’s hand. “Cheer up, my dear mother,” said he, “and make the best of it. I love you dearly, and should be very sorry to see you get a thrashing; however grieved I might be, I could not help for there is no standing up against Zeus. [590] Once before when I was trying to help you, he caught me by the foot and flung me from the celestial threshold. All day long from morning till evening was I falling, till at sunset I came to ground in the island of Lemnos, and there I lay, with very little life left in me, till the Sintians came and tended me.”

[595] Ivory-armed Hera smiled at this, and as she smiled she took the cup from her son’s hands.

Iliad 1.571–596, Sourcebook

Thetis asks Hephaistos for armor for Achilles, and he constructs the beautiful armor which Thetis gives directly to her son.

Aphrodite directly rescues Aeneas on the battlefield when he is attacked by Diomedes: she is not a warlike goddess and has no armor, only the folds of her robe; as a result she is wounded in the attempt:

And now Aeneas, king of men, would have perished then and there, had not his mother, Zeus’ daughter Aphrodite, who had conceived him by Anchises when he was herding cattle, been quick to mark, and thrown her two white arms about the body of her dear son. [315] She protected him by covering him with a fold of her own fair garment, lest some Danaan should drive a spear into his breast and kill him.

Thus, then, did she bear her dear son out of the fight.

Iliad 5.311–317, Sourcebook

…

[330] Now the son of Tydeus was in pursuit of the Cyprian goddess, spear in hand, for he knew her to be feeble and not one of those goddesses that can lord it among men in battle like Athena or Enyo, the waster of cities, and when at last after a long chase he caught her up, [335] he flew at her and thrust his spear into the flesh of her delicate hand. The point tore through the ambrosial robe which the Graces had woven for her, and pierced the skin between her wrist and the palm of her hand, so that the immortal blood, [340] or ikhōr, that flows in the veins of the blessed gods, came pouring from the wound; for the gods do not eat bread nor drink wine, hence they have no blood such as ours, and are immortal. Aphrodite wailed aloud, and let her son fall, but Phoebus Apollo caught him in his arms, [345] and hid him in a cloud of darkness

Iliad 5.330–345, Sourcebook

Thetis always knows Achilles will not live long, while Aphrodite, although her son is also mortal, knows his fated way is to have a longer life, as described by Poseidon who says “And presently the might [biē] of Aeneas will be king of the Trojans and his children’s children, who are to be born hereafter.” (Iliad 20.307–308, Sourcebook)

In this lament of Thetis we hear about Achilles’ fate:

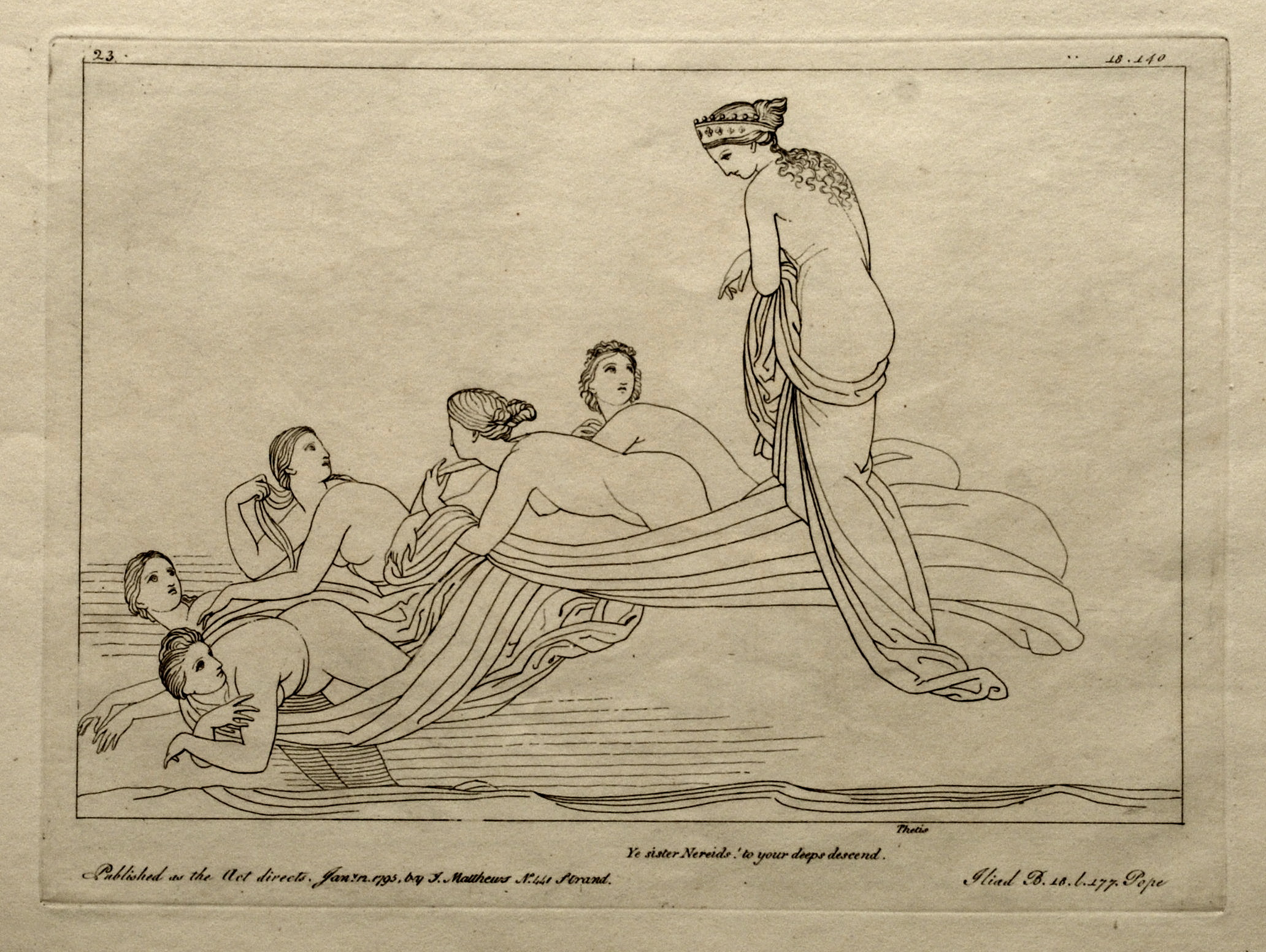

“Listen,” she cried, “sisters, daughters of Nereus, that you may hear the burden of my sorrows. 54 Ah me, the pitiful one! Ah me, the mother, so sad it is, of the very best. [55] I gave birth to a faultless and strong son, 56 the very best of heroes. And he shot up [anedramen] equal [īsos] to a seedling [ernos]. 57 I nurtured him like a shoot in the choicest spot of the orchard, 58 only to send him off on curved ships to Troy, to fight Trojan men. 59 And I will never be welcoming him [60] back home as returning warrior, back to the House of Peleus. 61 And as long as he lives and sees the light of the sun, 62 he will have sorrow [akh-nutai], and though I go to him I cannot help him. Nevertheless I will go, that I may see my dear son and learn what sorrow [penthos] has befallen him though he is still holding aloof from battle.”

Iliad 18.52–64, Sourcebook

And, in the end, she has to make Achilles aware of it too:

Thetis wept and answered, [95] “Then, my son, is your end near at hand—for your own death awaits you full soon after that of Hector.”

Iliad 18.94–96, Sourcebook

Aphrodite is an Olympian god, while Thetis is not, as Apollo points out to Aeneas as he is about to face Achilles in battle:

“Nay, hero, pray [105] to the ever-living gods, for men say that you were born of Zeus’ daughter Aphrodite, whereas Achilles is son to a goddess of inferior rank. Aphrodite is child to Zeus, while Thetis is but daughter to the old man of the sea…”

Iliad 20.104–107, Sourcebook

Does their respective ranking as goddesses have a bearing on why their respective sons have different fated ways?

What other divine mothers appear in Homeric epic? Is there a difference between divine mothers of immortals, and divine mothers of mortals?

Join us in the forum to share examples.

Coming up: Part 2: Mortal mothers

Notes

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2019.08.13. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

Iliad, translated by Samuel Butler, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray.

Image credits

Giovanni Battista Tiepolo. 1757. Thetis Consoling Achilles. public domain, Wikimedia Commons.

Benjamin West. 1806. Thetis Bringing Armor to Achilles II. public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Tyszkiewicz Painter Diomedes and Aeneas, MFA Boston 490BCE. Side B. via Perseus Digital Image Library

Flaxman: 1795 Thetis and the Nereids. Illustration to the Iliad. Creative Commons 3.0 Unported license via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images and online texts accessed September 2019.

___

Hélène, Janet, and Sarah are members of the Kosmos Society