In this part of our series on marriage in ancient Greek texts (following part 1: Music, and part 2: Wedding), we look at the courtship phase. How are suitors or prospective bridegrooms portrayed, what agency does the bride-to-be have, and how are marriages arranged?

Émile Benveniste, in Indo-European Language and Society[1], discusses how “there is, properly speaking, no Indo-European term for “marriage.”” He explains that the words are different for men and women:

“the important difference is that for the man the terms are verbal, and for the woman nominal.

In order to say that a man “takes a wife”, Indo-European employs forms of a verbal root *wedh- ‘lead’, especially “lead a woman to one’s home.” … Greek héedna (ἕεδνα) ‘marriage gift’.

Such was the expression in the most ancient stage and when certain languages found new words to express the notion of “to lead”, the new verb also assumed the value of “marry (a woman).” … Another verb is peculiar to Greek, gameîn (γαμεῖν), which has no certain correspondences.

…

Besides these verbs which denote the role of the husband we must place those which indicate the function of the father of the bride. The father, or in default of this his brother, has authority to “give” the young woman to her husband: πατρὸς δόντος ἒ ἀδελπιõ, as the Law of Gortyn, chapter viii, puts it. “Give” is the verb constantly used for this formal proceeding; it is found in various languages, generally with some variation in the preverb: Greek doûnai (δοῦναι), ekdoûnai (ἐκδοῦναι) … This constancy of expression illustrates the persistence of usages inherited from a common past and of the same family structure, where the husband “led” the young woman, whom her father has “given” him, to his home.[2]

For women, Benveniste shows there is “the absence of a special verb, indicates that the woman does not “marry”, she “is married.” She does not accomplish an act, she changes her condition.”

To what extent is this terminology still present in the expressions found in the ancient Greek texts, and are there other expressions and customs in evidence?

In the myths, one element seems to be that the father demands certain tasks to be fulfilled for the suitor to earn the bride. For example, Neleus demands a successful cattle-raid to be carried out for the hand of his daughter:

There is a cave inside the town [= Pylos], in which it is said that the cattle belonging to Nestor and to Neleus before him were kept.

{4.36.3} These cattle must have been of Thessalian stock [genos], having once belonged to Iphiklos the father of Protesilaos. Neleus demanded these cattle as bride gifts [hedna] for his daughter from her suitors [mnaasthai], and it was on their account that Melampos went to Thessaly to gratify [khairein] his brother Bias. He was put in bonds by the herdsmen of Iphiklos, but received them as his reward for the prophecies [verb, mantis] which he gave to Iphiklos at his request. So it seems the men of those days made it their business to amass wealth of this kind, herds of horses and cattle, if it is the case that Nestor desired to get possession of the cattle of Iphiklos and that Eurystheus, in view of the reputation of the Iberian cattle, ordered Hēraklēs to drive off the herd of Geryones.

{4.36.4} Eryx too, who was reigning then in Sicily, plainly had so violent a desire for the cattle from Erytheia that he wrestled in a contest [athla] with Hēraklēs, staking his kingdom on the match against these cattle. As Homer says in the Iliad, a hundred kine were the first of the bride gifts [hedna] paid [doûnai] by Iphidamas the son of Antenor to his bride’s father. This confirms my argument that the men of those days took the greatest pleasure [khairein] in cattle.

Pausanias 4.36.2–4.36.4, adapted from translation by Jones/Nagy, A Pausanias Reader[3]

Similar arrangements appear in some accounts of the wooing of Helen, for example:

But of all who came for the sake of the girl [kourē], the lord Tyndareus sent none away, nor yet received the gift [dōron] of any, but asked of all the suitors [mnēstēres] sure oaths [horkia], and bade them swear and vow with unmixed libations that no one else henceforth should do aught apart from him as touching the marriage [gamos] of the girl [kourē] with shapely arms; but if any man should cast off fear [nemesis] and reverence [aidōs] and take her by force [biē], he bade all the others together follow after and make him pay the penalty [poinē]. And they, each of them hoping to accomplish his marriage, obeyed him without wavering. But warlike Menelaus, the son of Atreus, prevailed [nikãn] against them all together, because he gave [poroûn] the greatest [gifts].

Hesiod, Fragment 68, Berlin Papyri, No 9739, (ll. 89-100) adapted from translation by H. G. Evelyn-White[4]

It is not clear what gifts are involved here.

In these scenarios, the father chooses the groom for his daughter. In Apollodorus’ version of the wooing of Helen, her father, Tyndareus, makes the selection and in addition arranges with Ikarios in the selection of a groom for his daughter, Penelope.

Seeing the multitude of them [= suitors], Tyndareus feared that the preference of one might set the others quarrelling; but Odysseus promised that, if he would help him to win Penelope in marriage [gamos], he would suggest a way by which there would be no quarrel [stasis]. And when Tyndareus promised to help him, Odysseus told him to exact an oath [horkos, verb] from all the suitors [mnēstēres] that they would defend the favoured bridegroom [numphios] against any wrong that might be done him in respect of his marriage [gamos]. On hearing that, Tyndareus put the suitors [mnēstēres] on their oath [horkos, verb], and while he chose Menelaos to be the bridegroom [numphios] of Helen, he solicited Ikarios to bestow [mnēsteuein] Penelope on Odysseus.

Apollodorus Library 3.10.9, adapted from translation by Sir James George Frazer[5]

Similarly, in Euripides Iphigenia in Aulis (685–703), it is clear that the father, Agamemnon, has apparently chosen a “groom” (Achilles) for his daughter Iphigenia—although this is not going to be a marriage, but a sacrifice, in order to obtain favorable winds for the expedition—and he refers to the marriage of Peleus and “the daughter of Nereus” [= Thetis]. Clytemnestra asks if this was “With the god’s having given [doûnai] her, or when he had taken her in spite of gods?” and perhaps tellingly “Zeus betrothed [enguᾶn] her, and her guardian gave [doûnai] her.” Even among the gods, it seems, the decisions are made for her.

In that scenario of a supposed marriage, Agamemnon is ostensibly acting to benefit the whole group. Here is an example of the wider community being directly involved in the decision to give a girl in marriage to a dead hero—and, indeed, for punishing a violation and for performing a ritual compensation. There is also a contest!

Here one of his [= Odysseus’] sailors got drunk and violated [biā, verb] a girl [parthenos], for which offense [a-dikē] he was stoned to death by the natives.

{6.6.8} … But the superhuman force [daimōn] of the stoned man never ceased killing without distinction the people of Temesa, attacking both old and young, until, when the inhabitants had resolved to flee from Italy for good, the Pythian priestess forbade them to leave Temesa, and ordered them to propitiate the Hero [Hērōs = the daimōn of the sailor], setting him a sanctuary [temenos] apart and building a temple, and to give [doûnai] him every year as wife the fairest girl [parthenos] in Temesa.

{6.6.9} So they performed the commands of the god and suffered no more terrors from the daimōn. But Euthymos happened to come to Temesa just at the time when the daimōn was being propitiated in the usual way; learning what was going on, he had a strong desire to enter the temple, and not only to enter it but also to look at the girl [parthenos]. When he saw her, he first felt pity and afterwards love for her. The girl swore to marry him if he saved [sozein] her, and so Euthymos with his armor on awaited the onslaught of the daimōn.

{6.6.10} He won the fight, and the Hero [hērōs] was driven out of the land and disappeared, sinking into the depth of the sea. Euthymos had a distinguished [epiphanēs] wedding [gamos], and the inhabitants were freed from the daimōn forever. I heard another story also about Euthymos, how he reached extreme old age and escaping again from death, departed from among men in another way.

Pausanias 6.6.7–6.6.10, adapted from A Pausanias Reader[6]

Another, related, theme is that the prospective suitors engage in a direct contest, as we have seen with Euthymos’ battling the ghost and winning the girl.

Sophocles’ Trachiniae refers to another such contest, between the river god and Herakles (the Chorus is speaking):

But, when this bride [akoitis] was to be won, [505] who were the massive rivals that entered the contest for her nuptials [gamos]? Who stepped forward to the ordeal [āthlos] of battle [agōnes] full of blows and raising dust?

One was a mighty river-god, the form of a bull, high-horned and four-legged, [510] Achelous, from Oeniadae. The other came from Thebes, home of Bacchus, brandishing his resilient bow, his spears and club; he was the son of Zeus. These two then met in a mass, lusting to win a bride [lekhos], [515] and the Cyprian goddess of nuptial joy was there with them, acting as sole umpire.

There was clatter of fists and clang of bow and crash of a bull’s horns mixed together; [520] then there were close-locked grapplings and deadly blows from foreheads and loud deep cries from both. Meanwhile the delicate beauty sat on the side of a hill that could be seen from afar, [525] awaiting the husband [akoitēs] that would be hers.

Sophocles Trachiniae 504–525, adapted from translation by Sir Richard Jebb[7]

A competition also features in the Odyssey when Penelope declares that she will hold an archery contest. The suitors also bring her gifts of jewelry; these could be bride-gifts [hedna] or the “price of admission”, and/or could be themselves displays of competitive behavior—to demonstrate who has brought the best gift (as we saw above with Menelaos in the Hesiod fragment).

Then Antinoos said, [285] “Circumspect Queen Penelope, daughter of Ikarios, take as many presents as you please from any one who will give them to you; it is not well to refuse a present; but we will not go about our business nor stir from where we are, till you have married [gamasthai] the best [aristos] man among us whoever he may be.”

[290] The others applauded what Antinoos had said [mūthos], and each one sent his herald [kērux] to bring his present. Antinoos’ man returned with a large and lovely robe [peplos] most exquisitely pattern-woven [poikilos]. It had twelve beautifully made brooch pins of pure gold with which to fasten it.

[295] Eurymakhos immediately brought her a magnificent chain of gold and amber beads that gleamed like sunlight. Eurydamas’ two men [therapontes] returned with some earrings fashioned into three radiant pendants which glistened in beauty [kharis]; while king Peisandros [300] son of Polyktor gave her a necklace of the rarest workmanship, and every one else brought her a beautiful present of some kind. Then the queen went back to her room upstairs, and her maids brought the presents after her.

Meanwhile the suitors took to singing and dancing [terpsasthai], [305] and stayed till evening came. They danced and sang [terpsasthai] till it grew dark; they then brought in three braziers to give light, and piled them up with chopped firewood very well seasoned and dry, [310] and they lit torches from them, which the maids held up turn and turn about.

Odyssey 15.285–311, adapted from Sourcebook[8]

Unusually Penelope herself is setting the terms of marriage, but she is— apparently—a widow and has not returned to her father’s house where suitors would bring her marriage-gifts (a scenario that was suggested earlier at 2.50–54, and 2.130–135; however, Telemachus cannot send her back because he cannot afford to return her original bride-price—the dowry provided by her father Ikarios).

But what about marriages where there is no parental consent? What kind of customs and terminology are there in the texts?

One example would be the marriage of Paris/Alexandros and Helen. She is sometimes portrayed as a willing partner, and sometimes as unwilling—and was, of course, already married. But either way, the man is again “leading away” the woman to his own home.

Other examples include Theseus helping his friend with “wooing” Korā:

Then he himself [= Theseus], to return [apodoûnai] the service of Peirithous, journeyed with him to Epirus, in quest of the daughter of Aidoneus [= Hades] the king of the Molossians. This man called his wife Phersephone, his daughter Korā [= kourē], and his dog Cerberus, with which beast he ordered that all those wooing [mnaasthai] his daughter should fight, promising her to him that should overcome it. However, when he learned that Peirithous and his friend were come not as suitors [mnēstēres], but to steal away [harpazein] his daughter, he seized them both. Peirithous he put out of the way at once by means of the dog, but Theseus he kept in close confinement.

Plutarch, Life of Theseus 31.4, adapted from translation by Bernadotte Perrin.[9]

His precautions are well-founded: before this episode, Theseus, with the help of his friend, had led away Helen before she was even of marriageable age:

Theseus was already fifty years old, according to Hellanicus, when he took part in the matter of Helen, who was not of marriageable age [hōrā]. Wherefore some writers, thinking to correct this heaviest accusation against him, say that he did not carry off [harpazein] Helen himself, but that when Idas and Lynceus had carried her off [harpazein] he received her in charge and watched over her and would not surrender her to the Dioscuri when they demanded her; or, if you will believe it, that her own father, Tyndareus, entrusted [paradoûnai] her to Theseus, for fear of Enarsphorus, the son of Hippocoon, who sought to take Helen by force while she was yet a child [nēpios]. But the most probable account, and that which has the most witnesses in its favour, is as follows.

Theseus and Peirithous went to Sparta in company, seized [harpazein] the girl [kourē] as she was singing-and-dancing [verb, khoros] in the temple of Artemis Orthia, and fled away with her. Their pursuers followed them no farther than Tegea, and so the two friends, when they had passed through Peloponnesus and were out of danger, made a compact with one another that the one on whom the lot fell should have Helen to wife, but should assist the other in prodcuring another marriage [gamos].

Plutarch Life of Theseus 31.1–31.2, adapted from translation by Bernadotte Perrin

Theseus wins, but since she is too young he doesn’t actually marry her at this stage.

In another story, the father tries to retain control—again by means of a contest, although one with a more dangerous twist—but his daughter falls in love and is able to influence matters in her choice of husband:

[E.2.4] Now Oinomaos, the king of Pisa, had a daughter Hippodamia, and whether it was that he loved [erân] her, as some say, or that he was warned by an oracle that he must die by the man that married [gameîn] her, no man got her to wife [gunē]; for her father could not persuade her to cohabit with him, and her those wooing [mnēsteuein] her were put by him to death.

[E.2.5] For he had arms and horses given him by Arēs, and he offered as a prize [athlon] to the suitors [mnēstēres] marriage [gamos] [= with his daughter], and each suitor [mnēstēr] was bound to take up Hippodamia on his own chariot and flee as far as the Isthmus of Corinth, and Oinomaos straightway pursued him, in full armour, and if he overtook him he slew him; but if the suitor were not overtaken, he was to have Hippodamia to wife [gunē]. And in this way he slew many who were wooing [mnēsteuein], some say twelve; and he cut off the heads of the suitors [mnēstēres] and nailed them to his house.

[E.2.6] So Pelops also came in courtship [mnēsteia]; and when Hippodamia saw his beauty, she conceived a passion [erōs] for him, and persuaded Myrtilos, son of Hermes, to help him; for Myrtilos was charioteer to Oinomaos.

[E.2.7] Accordingly Myrtilos, being in love with [erân] her and wishing to gratify [kharis, verb] her, did not insert the linchpins in the boxes of the wheels, and thus caused Oinomaos to lose the race and to be entangled in the reins and dragged to death; but according to some, he was killed by Pelops. And in dying he cursed Myrtilos, whose treachery he had discovered, praying that he might perish by the hand of Pelops.

[E.2.8] Pelops, therefore, got Hippodamia; and on his journey, in which he was accompanied by Myrtilos, he came to a certain place, and withdrew a little to fetch water for his wife [gunē], who was thirsty; and in the meantime Myrtilus tried to rape her [= assault + biā, verb]. But when Pelops learned that from her, he threw Myrtilos into the sea, called after him the Myrtoan Sea, at Cape Geraistos; and Myrtilos, as he was being thrown, uttered curses against the house of Pelops.

Apollodorus Epitome 2.4–2.8, adapted from translation by Sir James George Frazer[10]

And if the brides did not consent, their ultimate recourse was to murder their husbands on their wedding night, as did forty-nine out of the fifty daughters of Danaos:

Then there was the wise [sophos] Aigyptos, who lived on Egyptian soil, ill-fated father of many children, who begat all those flocks of short-lived sons; and Danaos who went abroad, who armed his daughters against that family of men, and drew a wedding [gamios]-sword, when the marriage-chambers [pastoi] were reddened with blood of the murdered bridegrooms [humenaioun], and with secret swords on armed beds, Enyo the female bedded Ares the male naked and helpless.

Nonnus of Panpolis Dionysica 3.300–307, adapted from translation by W.H.D. Rouse[11]

The myth of Danaos is alluded to by Pausanias, referring to a later part of the story after Danaos and forty-nine of his daughters had successfully escaped; their father then held a contest for prospective suitors:

{3.12.2} It is said that Ikarios proposed a contest [agōn] of a foot-race for the wooers [mnēstēres] of Penelope; that Odysseus won is plain, but they say that the competitors were let go [aphethenai] for the race along the Aphetaid Road. In my opinion, Ikarios was imitating Danaos when he held the contest [agōnisma] of a running-race. For Danaos contrived the following plan to solve the difficulty about his daughters. Nobody would take [agagesthai] a wife [gunē] from among them because of their pollution [miasma] so Danaos sent round a notice that he would give away [doûnai] his daughters without bride-gifts [hedna], and that each [suitor] could choose the one whose beauty pleased him most. A few men came, among whom he held a contest [agōn] of a foot-race, the first comer was allowed to choose before all the others, after him the second, and so on to the last. The daughters that were left had to wait until other suitors [mnēstēres] arrived and competed in another contest [agōn] of a foot-race.

Pausanias 3.12.1–3.12.2, adapted from Pausanias Reader[12]

Odysseus’ winning Penelope in a foot-race is a different version of his courtship than the one provided by Apollodorus above! The example of Danaos in setting a contest also inspired Antaeus, as recounted by Pindar in a story about the ancestors of the victor who is being celebrated in this ode:

… for the sake of a Libyan woman they [= the ancestors] went to the city of Irasa, as suitors [mnēstēres] of the very famous daughter [kourē] of Antaeus with the beautiful hair. Many excellent kinsmen sought her, and many strangers [xenoi] too, since her beauty was marvellous. They wanted [110] to pluck the flowering fruit [karpos] of golden-crowned Youth [Hēbē]. But her father, cultivating for his daughter a more renowned marriage [gamos], heard how Danaus once in Argos had found for his forty-eight daughters [parthenoi], before noon overtook them, a very swift marriage [gamos]. For right away he stood the whole band [khoros] of suitors at the end [terma] of a course [agōn], [115] and told them to decide [diakrinein] with contests [aethloi] of footraces which of the heroes [hērōes], who came to be bridegrooms [gambroi], would take which bride. The Libyan too made such an offer in joining [harmozein] his daughter [kourē] with a husband [numphios]. He placed her at the goal, when he had arrayed [kosmeîn] her as the crowning prize [telos], and in their midst he announced that that man should lead [ap-agesthai] her to his home, whoever was the first to leap forward [120] and touch her robes. There Alexidamus, when he had sped to the front of the swift race [dromos], took the noble girl [parthenos] by the hand in his hand and led [agein] her through the crowd of Nomad horsemen. They cast on that man many leaves and garlands [stephanoi], [125] and before he had received many wings for his victories [nikē].

Pindar Pythian 9 105–125, adapted from translation by Diane Arnson Svarlien[13]

The contest, which is a foot-race, is literally a “contest of feet”. Although this is a race, the group of suitors (translated here as “band”) is described as khoros, the same word that is used for a group who are singing-and-dancing, where a different type of footwork is used.

There is also reference to bachelors going to a dance on Scheria at Odyssey when Nausicaa asks her father if she can to to the shore to wash clothes:

Moreover, you have five sons at home, two of them married, while the other three are flourishing [thalethein] bachelors [ēitheoi]; you know they always like to have clean linen [65] when they go to a dance [khoros], and I have been thinking in my phrēn about all this.”

She did not say a word about her own wedding [gamos], for she did not like to…

Odyssey 6.60–67, adapted from Sourcebook[14]

Could this be alluding to some sort of competitive ritual? After the athletic contests, Alkinoos arranges a display of dancing to impress (or intimidate or warn?) Odysseus:

I want the best of the Phaeacian acrobatic dancers [bētarmones] 251 to perform their sportive dance [paizein], so that the stranger, our guest, will be able to tell his near-and-dear ones, 252 when he gets home, how much better we (Phaeacians) are than anyone else 253 in sailing and in footwork, in dance and song. … 258 And the organizers [aisumnētai], the nine selectmen, all got up 259 —they belonged to the district [dēmos]—and they started arranging everything according to the rules of the competition [agōn]. [260] They made smooth the place of the singing and dancing [khoros], and they made a wide space of competition [agōn]. 261 The herald [kērux] came near, bringing the clear-sounding phorminx 262 for Demodokos. He moved to the center of the space. At his right and at his left were boys [kouroi] 263 in the first stage of adolescence [prōthēboi], standing there, well versed in dancing [orkhēthmos]. 264 They pounded out with their feet a dance [khoros], a thing of wonder, and Odysseus [265] was observing the sparkling footwork. He was amazed in his heart [thūmos].

Odyssey 8.250–253, 258–265, Sourcebook[15]

This dancing is clearly competitive, and given the age of the youths it could be part of a ritual contest for those on the verge of finding prospective brides.

A similar scene appears on the Shield of Achilles where the presence of girls makes it clearer:

[590] The renowned one [= the god Hephaistos], the one with the two strong arms, pattern-wove [poikillein] in it [= the Shield of Achilles] a khoros. 591 It [= the khoros] was just like the one that, once upon a time in far-ruling Knossos, 592 Daedalus made for Ariadne, the one with the beautiful tresses [plokamoi]. 593 There were young men [ēitheoi] there, and girls [parthenoi] who are courted with gifts of cattle, 594 and they all were dancing with each other, holding hands at the wrist. [595] The girls were wearing delicate dresses, while the boys were clothed in tunics [khitōn plural] 596 well-woven, gleaming exquisitely, with a touch of olive oil. 597 The girls had beautiful garlands [stephanai], while the boys had knives 598 made of gold, hanging from knife-belts made of silver. 599 Half the time they moved fast in a circle, with expert steps, [600] showing the greatest ease, as when a wheel, solidly built, is given a spin by the hands 601 of a seated potter, who is testing it whether it will run well. 602 The other half of the time they moved fast in straight lines, alongside each other. 603 A huge crowd stood around the place of the song-and-dance [khoros] that rouses desire, 604 and they were feeling delight [terpesthai]; in their midst sang-and-danced [melpesthai] a divine singer [aoidos], [605] playing on the special lyre [phorminx]; two special dancers [kubistētēre] among them 606 were swirling as he led [exarkhein] the singing and dancing [molpē] in their midst.

Iliad 18.590–606 adapted from Sourcebook[16]

So both athletics and dancing could be a ritualized form of contest to take the place of the more aggressive contests of fighting, or bringing cattle, or of capturing a young woman to lead home as a bride.

What other examples are there of fighting over a woman, or competing through ordeals or contests? Are there other over-protective father figures? And which woman claim agency in choosing their husbands?

Selected vocabulary

In Pindar and some other passages the Greek has dialectal forms; the standard dictionary forms are listed here. Definitions based on those in LSJ[17]

agein [ἄγειν]; middle agagesthai [ἀγαγέσθαι] lead, fetch, carry off

akoitis [ἄκοιτις] spouse, wife

akoitēs [ἀκοίτης] bedfellow, spouse, husband

dōron [δῶρον] gift

doûnai [δοῦναι] give, deliver up, offer

ēitheos [ἠίθεος] unmarried youth

enguân [ἐγγυᾶν] to betroth, (of a father) to give (daughter) in marriage

erân [ἐρᾶν] to love, desire

erōs [ἔρως] love, desire, passion

gambros [γαμβρός] son-in-law, brother-in-law; betrothed, bridegroom

gameîn [γαμεῖν] to marry in the active, marry, take to wife; in the middle, gamasthai, [γήμασθαι] “give oneself or one’s child in marriage or betrothal”

gamios /gamēlios [γάμιος / γαμήλιος] bridal, belonging to a wedding

gamos [γάμος] wedding, marriage

gunē [γυνή] woman, wife

harpazein [ἁρπάζειν] snatch away, carry off, seize

hedna [ἕδνα] wedding-gifts, bride-price

harmozein [ἁρμόζειν] to join (related to the noun harmoniā)

humenaioun [ὑμεναίουν] wed, sing the wedding song

kourē [κουρή] girl, daughter, bride

lekhos [λέχος] bed, marriage-bed, marriage, spouse

mnaasthai [μνάασθαι] to woo, court

mnēsteia [μνηστεία] wooing, courtship

mnēstēr [μνηστήρ], pl. mnēstēres, suitor

mnēsteuein [μνηστεύειν] court, seek in marriage; promise in marriage, betroth

numphios [νυμφίος] bridegroom

parthenos [παρθένος] girl (in some contexts, virgin)

pastos [παστός] bridal chamber

Notes

1 Benveniste, Émile. 1973. Indo-European Language and Society. Miami. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Benveniste.Indo-European_Language_and_Society.1973

2 Benveniste 1973. Book 2: “The Vocabulary of Kinship, Chapter 4: The Indo-European Expression for “Marriage””. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Benveniste.Indo-European_Language_and_Society.1973

3 Pausanias Description of Greece, Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.prim-src:A_Pausanias_Reader_in_Progress.2018-

Greek: Pausanias. Pausaniae Graeciae Descriptio, 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903.

Online at Perseus

4 Hesiod, Homeric Hymns, Epic Cycle, Homerica. Translated by Evelyn-White, H G. Loeb Classical Library Volume 57. London: William Heinemann, 1914. The English translation is available at

https://www.theoi.com/Text/HesiodCatalogues.html

5 Apollodorus. Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer’s notes.

Engish: Online at Perseus

Greek: Online at Perseus

6 English: Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.prim-src:A_Pausanias_Reader_in_Progress.2018-#VI

Greek, online at Perseus

Calvert Watkins in How to Kill a Dragon (1995,Oxford) gives this as an example of a Hero and Monster episode: “The HERO and the MONSTER are in fact frequently ambiguous and ambivalent.” (p399)

7 Sophocles. The Trachiniae of Sophocles. Edited with introduction and notes by Sir Richard Jebb. Sir Richard Jebb. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. 1892.

Online at Perseus

Greek: Sophocles. Sophocles. Vol 2: Ajax. Electra. Trachiniae. Philoctetes With an English translation by F. Storr. The Loeb classical library, 21. Francis Storr. London; New York. William Heinemann Ltd.; The Macmillan Company. 1913.

Online at Perseus

8 Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2019.12.12. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

English: Homeric Odyssey translated by Samuel Butler, revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Greek: Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919.

Online at Perseus

9 Plutarch. Plutarch’s Lives. with an English Translation by. Bernadotte Perrin. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. 1.

English, online at Perseus

Greek, online at Perseus The daughter’s name, Kora, is a version of the word kourē.

10 English: Apollodorus. Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer’s notes.

Online at Perseus, starting at 2.4

Greek, from the same edition, online at Perseus

Frazer’s note to 2.4 says: “The following account of the wooing and winning of Hippodamia by Pelops is the fullest that has come down to us.” and provides a helpful comparison with other versions.

11 English: Nonnus, Dionysiaca. Translated by Rouse, W H D. Loeb Classical Library Volumes 344, 354, 356. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1940.

Online at theoi.com

Greek: Nonnus of Panopolis. Dionysiaca, 3 Vols. W.H.D. Rouse. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1940-1942.

Online at Perseus

12 English, online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek, online at Perseus

13 English: Odes. Pindar. Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

Online at Perseus

Greek: Pindar. The Odes of Pindar including the Principal Fragments with an Introduction and an English Translation by Sir John Sandys, Litt.D., FBA. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1937.

Online at Perseus

14 English, online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek, online at Perseus

15 English: online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek, online at Perseus

16 English: adapted from Sourcebook online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Greek: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

17 LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by. Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus

Image credits

Featured image: Detail from Polygnotos: Helen’s first abduction by Theseus, c 430–420 BCE. National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

Sharon Mollerus, from Flickr via Wikimedia Commons.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Helen%27s_First_Abduction_by_Theseus,_Polygnotos,_ca._430-420_BC.jpg

Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

Howard Pyle. 1905: Odysseus Advises King Tyndareus Concerning Helen’s Suitors, illustration from The Story of the Golden Age by James Baldwing.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Odysseus_advises_king_Tyndareus_concerning_Helen%27s_suitors.jpg

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Terracotta plaque with King Oinomaos and his charioteer Myrtilos. Roman, 27 BCE –68 CE. Metropolitan Museum of Art

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Terracotta_plaque_with_King_Oinomaos_and_his_charioteer_MET_DP120334.jpg

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nicolas Bertin. Hercules fighting Achelous, c1715–1730. National Museum in Warsaw.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bertin_Hercules_fighting_Achelous.jpg

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Euthymides: Theseus carrying off young Helen. Side A of Attic red-figure amphora c 510 BCE. Vulci. Staatliche Antikensammlungen.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theseus_Helene_Staatliche_Antikensammlungen_2309_n2.jpg

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Robinet Testard: The Danaides kill their husbands. 1496–1498. Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF). Cote : Français 874, folio 170v.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dana%C3%AFdes_tuant_leurs_maris_BnF_Fran%C3%A7ais_874_fol._170v.jpg

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

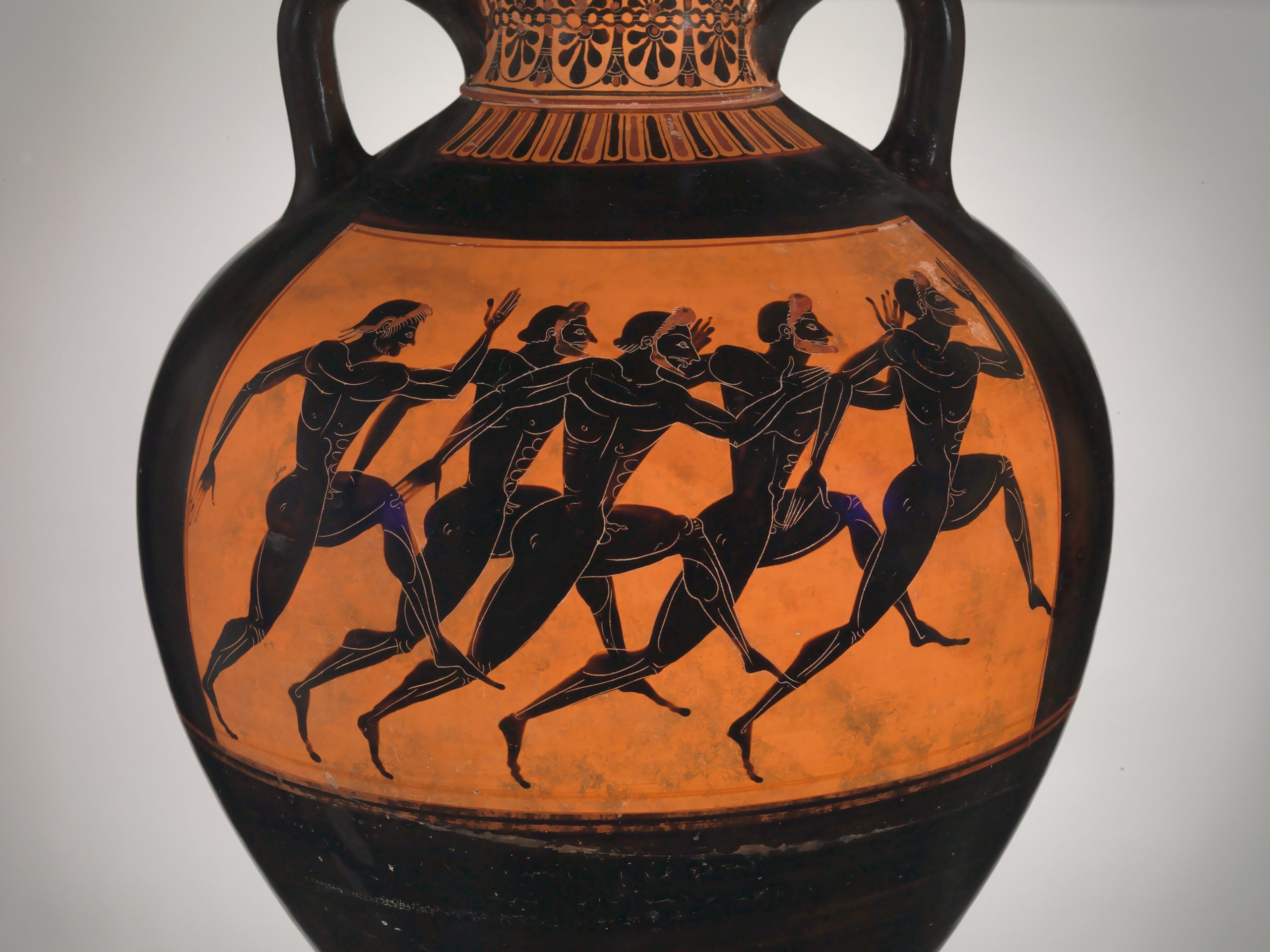

Euphiletos Painter: detail from Terracotta Panathenaic prize amphora c 530 BCE, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248902

Public domain

The Geranos (“Crane”) dance. Figure 11 from The Dance (by An Antiquary): Historic Illustrations of Dancing from 3300 B.C. to 1911 A.D., online at Project Gutenberg, public domain

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17289/17289-h/17289-h.htm#c2

The illustration was taken from a vase in the Museo Borbonico, Naples

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images and online texts accessed July 2020.

___

Sarah Scott, Hélène Emeriaud, and Janet Ozsolak are members of Kosmos Society