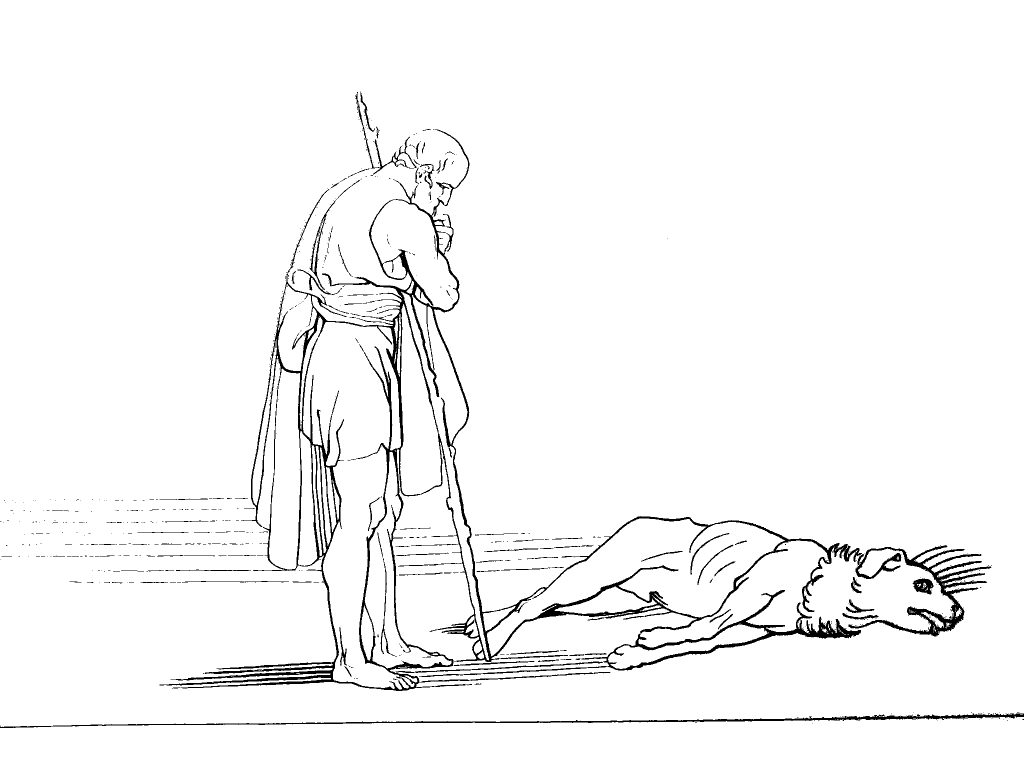

A poignant scene in the Homeric Odyssey is when Odysseus’ dog recognizes him upon his arrival in Ithaka in disguise. This faithful dog, now old and sick due to the lack of care by the servants dies shortly after this recognition scene. The bond between Odysseus and Argos still touches us deeply.

This was Argos, whom patient-hearted Odysseus had bred before setting out for Troy, but he had never had any work out of him. In the old days he used to be taken out by the young men [295] when they went hunting wild goats, or deer, or hares, but now that his master was gone he was lying neglected on the heaps of mule and cow dung that lay in front of the stable doors till the men should come and draw it away to manure the great field; [300] and he was full of fleas. As soon as he saw Odysseus standing there, he dropped his ears and wagged his tail, but he could not get close up to his master. …

“This hound,” answered Eumaios, “belonged to him who has died in a far country. If he were what he was when Odysseus left for Troy, [315] he would soon show you what he could do. There was not a wild beast in the forest that could get away from him when he was once on its tracks. But now he has fallen on evil times, for his master is dead and gone, and the women take no care of him. 320] Servants never do their work when their master’s hand is no longer over them, for Zeus of the wide brows takes half the goodness [aretē] out of a man when he makes a slave of him. As he spoke he went [325] inside the buildings to the hall where the suitors were, but Argos died as soon as he had recognized his master.

Odyssey 17.313–326, Sourcebook[1]

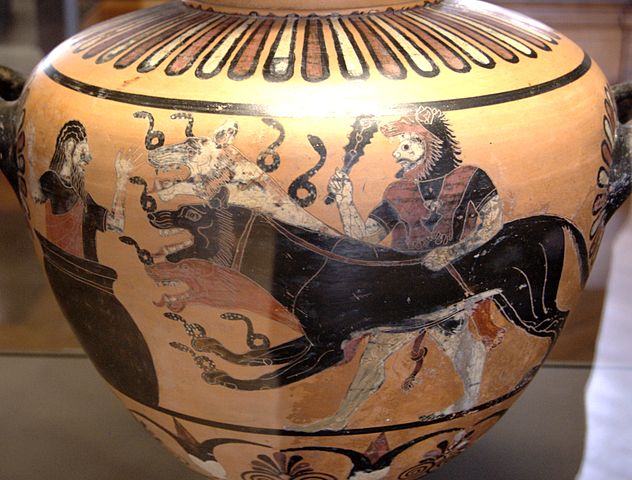

Unlike Argos, other mentions of dogs are quite peculiar. Aristophanes makes fun of many-headed Cerberus.

Aeacus

O impious, daring, and most shameless wretch,

O villain, double villain, and arch-villain,

It was you who came before, and stole my dog,

Poor Cerberus!Frogs 460[2]

When you wish to insult someone, go no further than telling them they have the likeness of a dog.

We have followed you, shameless one, for your pleasure, not ours—to gain satisfaction [tīmē] from the Trojans for you—you with the looks of a dog—and for Menelaos. [160] You forget this, and threaten to rob me of the prize [geras] for which I have toiled, and which the sons of the Achaeans have given me.

Iliad 1.158–162 Sourcebook[3]

An ominous site it is when the dogs don’t bark.

And when the god had duly finished all, he threw his sandals into deep-eddying Alpheus, [140] and quenched the embers, covering the black ashes with sand, and so spent the night while Selene’s soft light shone down. Then the god went straight back again at dawn to the bright crests of Cyllene, and no one met him on the long journey either of the blessed gods or mortal men, [145] nor did any dog bark.

Homeric Hymn (4) to Hermes 138–145, from The Homeric Hymns and Homerica[4]

You may also swear by the dog. According to W.R.M Lamb’s footnote to Plato’s Gorgias 461b “This favorite oath of Socrates was derived from Egypt, where the god Anubis was represented with a dog’s head; cf. Plat. Gorg. 482b.”[5]

[172e] Well, was that, he asked, not a proper admission?

Not to my mind, I answered.

In very truth, your words are strange! he said, Socrates.

Yes, by the Dog, I said, and they strike me too in the same way; and it was in view of this, just now, that I spoke of strange results that I noticed, and said I feared we were not inquiring rightly.Plato, Charmides 172e, from Plato in Twelve Volumes[6]

Strabo mentions how imaginations ran wild in relation to dogs.

But this ignorance in Homer’s case is not amazing, for those who have lived later than he have been ignorant of many things and have invented marvellous tales: Hesiod, when he speaks of “men who are half-dog,” of “long-headed men,” and of “Pygmies”; and Alcman, when he speaks of “web footed men”; and Aeschylus, when he speaks of “dog-headed men,” of “men with eyes in their breasts”, and of “one-eyed men” (in his Prometheus it is said); and a host of other tales.

The Geography of Strabo 7.3.6[7]

Death is terrible, but having your corpse eaten by dogs and birds is way worse.

[1] Anger [mēnis], goddess, sing it, of Achilles, son of Peleus— 2 disastrous [oulomenē] anger that made countless pains [algea] for the Achaeans, 3 and many steadfast lives [psūkhai] it drove down to Hādēs, 4 heroes’ lives, but their bodies it made prizes for dogs [5] and for all birds, and the Will of Zeus was reaching its fulfillment [telos]— 6 sing starting from the point where the two—I now see it—first had a falling out, engaging in strife [eris], 7 I mean, [Agamemnon] the son of Atreus, lord of men, and radiant Achilles.

Iliad 1.1-8 Sourcebook[8]

Agamemnon surely deserved the epithet given by Achilles.

But the son of Peleus again began railing at the son of Atreus, for he had not yet desisted from his anger [kholos]. [225] “Wine-bibber,” he cried, “you with the looks of a dog and the heart of a deer, you never dare to go out with the army of warriors in fight, nor yet with our chosen (best of the Achaeans) men in ambuscade.”

Iliad 1.223-227 Sourcebook[9]

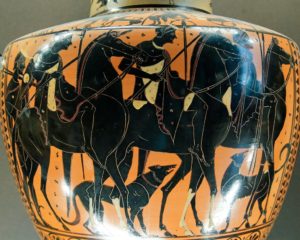

Suitors are compared to no other animal than dogs.

[35] “Dogs, did you think that I should not come back from the district [dēmos] of the Trojans? You have wasted my substance, have forced my women servants to lie with you, and have wooed my wife while I was still living.”

Odyssey 22.35–37, Sourcebook[10]

Even today, comparing someone to a dog is a great insult. Dog owners would not concur!

Notes

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2020-07-17. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

[2] Aristophanes, Frogs,translated by Matthew Dillon.

[3] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2020-07-17. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

[4] Anonymous, The Homeric Hymns and Homerica, Hymn 4 to Hermes with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Homeric Hymns. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

[5] Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 3 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1967.

[6] Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 8 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1955.

[7] Strabo. ed. H. L. Jones, The Geography of Strabo. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924.

[8] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2020-07-17. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

[9] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2020-07-17. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

[10] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2020-07-17. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG_ed.Sourcebook_H24H.2013-

Image Credits

Ulysses and his Dog, Flaxman, Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Herakles, Cerberus and Eurystheus Public Domain

Endymione and Selene Public Domain

Riders Public Domain

Images and texts accessed November 2020.

Janet Mayragul Ozsolak is a member of the Kosmos Society Editorial Team; and of the HeroesX Team, a MOOC on edX. She studied Sociology at Bogazici University, Istanbul, and has a MS in Education from the City College of New York.