A few thoughts about Orpheus, Musaeus and other poets.

It is striking to see the order in which Plato in the Apology of Socrates enumerates four Greek poets, heroes, who were part of his literary or oral poetry or musical references, and with whom Socrates would like to engage in conversation [logos] in Hades. Who wouldn’t?

If, when someone arrives in the world of Hādēs, he… finds…demigods [hēmi-theoi] who were righteous [dikaioi] in their own life—that would not be a bad journey [apo-dēmiā], now would it? To make contact with Orpheus and Musaeus and Hesiod and Homer—who of you would not welcome such a great opportunity?

Plato, The Apology of Socrates 41a, Sourcebook[1]

This order is also the one chosen by Aristophanes in his play The Frogs.

Aeschylus

This is the stuff poets should work on. Just look right from the start

how useful the noble race of poets has been.

For Orpheus taught us rites and to refrain from killing,

And Musaeus taught the cures of illness and oracles, and Hesiod

the working of the land, harvest seasons, plowing. Divine Homer,

Where did he get honor and glory if not from teaching useful things,

battle lines, courageous deeds, men’s armory?

Aristophanes The Frogs 1030–1036[2]

Aristophanes gives precious information about Museaus and Orpheus, about whom not much is known. Fortunately we have Hesiodic and Homeric poetry.

Certainly there is no mention of Musaeus and Orpheus in Hesiodic or in Homeric poetry. But Orpheus, the father of songs, is said by Pindar to come from Apollo:

“And from Apollo came the master lyrist, father of songs, [315] renowned Orpheus.

Pindar Pythian 4 177–178 [or 314–315][3]

The historians Hellanicus and Pherecydes record his name, the former making him the ancestor both of Homer and of Hesiod.[4]

Orpheus, Musaeus, Hesiod, Homer: are they listed according to their presumed date of birth?

As Gregory Nagy remarks, it is a possibility. With reference to Plato’s Apology of Socrates, and the heroes Socrates is reported as hoping to meet in the afterlife, Nagy says:

Among these heroes are the poets Orpheus, Musaeus, Hesiod, and Homer, listed in order of seniority, from the supposedly earliest to the latest.

The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours 22§17[5]

The ancient Greeks between the 6th century BCE and the second century CE were certainly closer to these poets in time than we are, but they did not all agree on who came first. They also had their doubts and even questioned the existence of some of these poets.

As Nagy remarks:

The Classical idea of Homer, as reflected in the conventional usage of most authors in what we know as the Classical period, pictured the poet of the Iliad and Odyssey as a figure more recent than such primeval and superannuated figures as Orpheus and his ‘scribe’ Musaeus. The idea of Homer as the oldest of all standard poets became a standard idea in its own right only in the era of Alexandrian scholarship. A moving force that led to this shift was Aristotle, who thought of Orpheus as a mythical figment postdating Homer. It needs to be emphasized that fifth-century authors like Herodotus were far ahead of their times in thinking of Homer as the oldest poet—older even than Orpheus and Musaeus.

Nagy 2004: “Homeric Echoes in Posidippus”[6]

Pausanias, as he describes the sanctuary of the Muses on the Helicon, depicts some representations of poets and musicians, and he is very frank about the difficulty of taking a stand on their age; unfortunately he does not give his own opinion:

As to the age of Hesiod and Homer, I have conducted very careful researches into this matter, but I do not like to write on the subject, as I know the quarrelsome nature of those especially who constitute the modern school of epic criticism.

Pausanias Description of Greece 9.30.3[7]

Pausanias gives a detailed description, as usual, of what he saw: on Mount Helicon [a statue of] Hesiod sits with a harp upon his knees, and, according to Pausanias this is strange because Hesiod, according to Hesiod himself in the Theogony, sang holding a laurel wand. Then Pausanias continues the description of the site telling us about Orpheus and the tales Greeks believe about him. Near a statue of Orpheus are beasts of stone and bronze listening to his singing. Orpheus had the reputation to be able to charm stones, beasts and even trees. The other famous tale about him is his descent, alive, to Hades to get his wife back. (Pausanias 9.30.3–4). There is also the beautiful story of nightingales nesting on his grave that sing more sweetly and louder than others (Pausanias 9.30.6)

Pausanias also writes:

In my opinion Orpheus excelled his predecessors in the beauty of his verse, and reached a high degree of power because he was believed to have discovered mysteries, purification from sins, cures of diseases and means of averting divine wrath… Some say that Orpheus came to his end by being struck by a thunderbolt, hurled at him by the god because he revealed sayings in the mysteries to men who had not heard them before. Others have said that his wife died before him, and that for her sake he came to Aornum in Thesprotis, where of old was an oracle of the dead. He thought, they say, that the soul of Eurydice followed him, but turning round he lost her, and committed suicide for grief…

Whoever has devoted himself to the study of poetry knows that the hymns of Orpheus are all very short, and that the total number of them is not great. The Lycomidae know them and chant them over the ritual of the mysteries. For poetic beauty they may be said to come next to the hymns of Homer, while they have been even more honored by the gods…

Pausanias 9.30.4–6, 9.30.12

Pausanias, then, is agreeing with Aristophanes’ short statement about Orpheus who taught us rites. We cannot compare his verses with Homer’s, to verify if they indeed come next to the hymns of Homer; unhappily we do not have much poetry from him, just fragments quoted by others.

Euripides mentions Orpheus and Musaeus in several plays. Orpheus’ power to move rocks is envied by Iphigenia.

Iphigenia

If I had the eloquence of Orpheus, my father, to move the rocks by chanted spells to follow me, or to charm by speaking anyone I wished, I would have resorted to it.

Euripides Iphigenia in Aulis 1211–1214”[8]

And in another play, The Bacchae, Orpheus’ other powers are praised.

Chorus

Where on Nysa which nourishes wild beasts, or on Corycian heights, do you lead with your thyrsos the bands of revelers? [560] Perhaps in the deep-wooded lairs of Olympus, where Orpheus once playing the lyre drew together trees by his songs, drew together the beasts of the fields.

Euripides Bacchae 556–564[9]

In the Symposium, Plato offers a different version of Orpheus’ descent to Hades to retrieve his wife, Eurydice, who according to Plato was only a phantom [φάσμα], therefore not being able to accomplish his purpose [ἀτελῆ] not courageous enough, like Alcestis, to die for his lovely wife.[10]

In another dialogue, Protagoras, Plato accuses Homer, Hesiod, Orpheus and Musaeus of sophistry, disguised in poetry for Homer and Hesiod, or of mystic rites and soothsayings, for Orpheus and Musaeus.[11]

It is certainly more complicated to find information about Musaeus. Many different myths exist about his life. Was he a son of Orpheus?

Aristotle in the Politics quotes one fragment of his poetry:

[20] but we all pronounce music to be one of the pleasantest things, whether instrumental or instrumental and vocal music together at least Musaeus says, ‘Song is man’s sweetest joy,’ and that is why people with good reason introduce it at parties and entertainments, for its exhilarating effect, so that for this reason also one might suppose that the younger men ought to be educated in music.”

Aristotle Politics 8.1339b[12]

And Pausanias agrees to give him the authorship of one work: a hymn to Demeter written for the Lycomidae.[13]

In a special way, Orpheus, Musaeus, Hesiod and Homer, didn’t they all seem to be related to the Muses? Was Orpheus the son of the Muse Calliope? Did Musaeus get his name from the Muses? Was he the son of Orpheus?

Hesiod was taught by the Muses, as he says himself at the beginning of the Theogony[14], and his name means ‘he who sends forth the voice’.

The name Hēsiodos means ‘he who sends forth the voice’, corresponding to the description of the Muses themselves at lines 10, 43, 65, 67. The element -odos ‘voice’ of Hēsiodos is apparently cognate with audē ‘voice’, the word used at line 31 to designate what was ‘breathed’ into Hesiod by the Muses.

Nagy, 2009.“Hesiod and the Ancient Biographical Traditions”[15]

As for Homer, as explained by Nagy:

Homēros (Ὅμηρος, Thucydides 3.104.4). The morphology of this name can be explained as a compound formation *homāros meaning ‘he who fits [the song] together’, composed of the prefix homo (ὁμο) ‘together’ and the root of the verb arariskein (ἀραρίσκειν)”[16]

Notes

1 Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook: Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English. Gregory Nagy. 2013.

Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

https://chs.harvard.edu/book/the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours-sourcebook

Plato The Apology of Socrates Translated by Benjamin Jowett. Adapted by Miriam Carlisle, Thomas E. Jenkins, Gregory Nagy, and Soo-Young Kim

2 Aristophanes. Frogs. Matthew Dillon.

Available on Perseus

3 Pindar, Pythian 4 Steven J. Willett, Ed. Pythian 4. Pindar. Steven J. Willett. 2001.

Verses 177–178 are numbered 314–315 in some editions

Available on Perseus

4 Cited in the entry on Orpheus in A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology William Smith, Ed.

Available on Perseus

5 Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

6 Nagy, Gregory: Chapter 5: “Homeric Echoes in Posidippus” in Acosta-Hughes, Benjamin, Elizabeth Kosmetatou, and Manuel Baumbach, eds. 2004. Labored in Papyrus Leaves: Perspectives on an Epigram Collection Attributed to Posidippus (P.Mil.Vogl. VIII 309). Hellenic Studies Series 2. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies:

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_AcostaHughesB_etal_eds.Labored_in_Papyrus_Leaves.2004

7 Pausanias. Pausanias Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918.

Available on Perseus

8 Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis

E. P. Coleridge, Ed. Euripides. The Plays of Euripides, translated by E. P. Coleridge. Volume II. London. George Bell and Sons. 1891.

Available on Perseus

9 Euripides, Bacchae

T. A. Buckley, Ed. Euripides. The Tragedies of Euripides, translated by T. A. Buckley. Bacchae. London. Henry G. Bohn. 1850.

Available on Perseus

10 Plato, Symposium 179d.

Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by Harold N. Fowler. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925.

Available on Perseus

11 Plato Protagoras 316d.

Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 3 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1967.

Available on Perseus

12 Aristotle. Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vol. 21, translated by H. Rackham. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1944

Available on Perseus

13 Pausanias Description of Greece 1.22.7

Available on Perseus

14 Hesiod Theogony 22.

Hesiodic Theogony. 1–115: Translated by Gregory Nagy; 116–1022: Translated by J. Banks Adapted by Gregory Nagy. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://chs.harvard.edu/primary-source/hesiod-theogony-sb/

15 Nagy, Gregory. 2009. “Hesiod and the Ancient Biographical Traditions”, ‘The names of Hesiod and Homer’, pp287–288

https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-hesiod-and-the-ancient-biographical-traditions/

16 Ibid

Image credits

Sarcophage of the Muses, Marble, (200CE) Louvre. Photo: Kosmos Society

Cades, Orpheus charming animals, Louvre. Photo: Kosmos Society

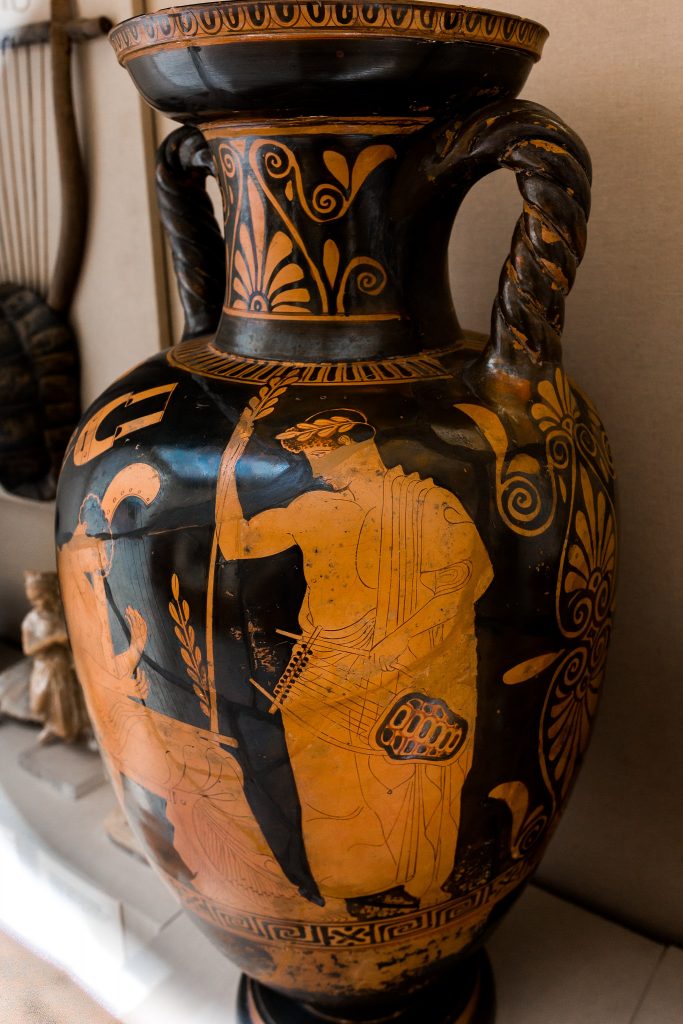

Peleus Painter: Musaeus with Melousa. c 440 BCE.

Photo: ArchaiOptix, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

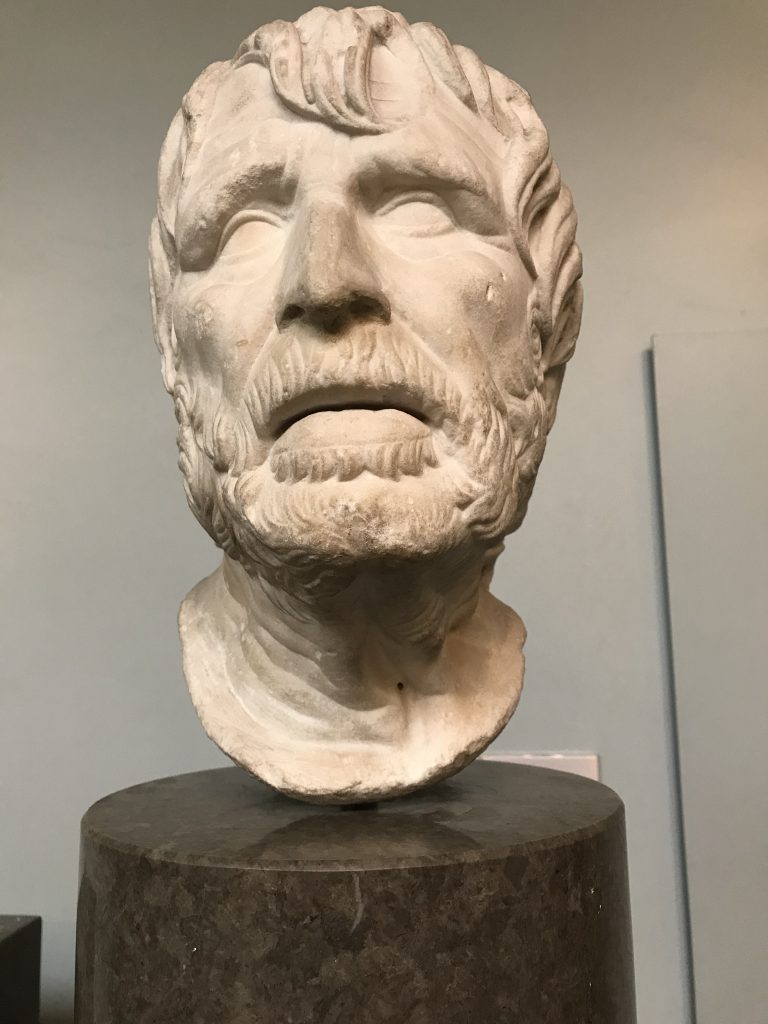

Marble head of an old man, perhaps the poet Hesiod, Roman copy after a lost Hellenistic original of the 2nd century BCE, British Museum. Photo: Kosmos Society

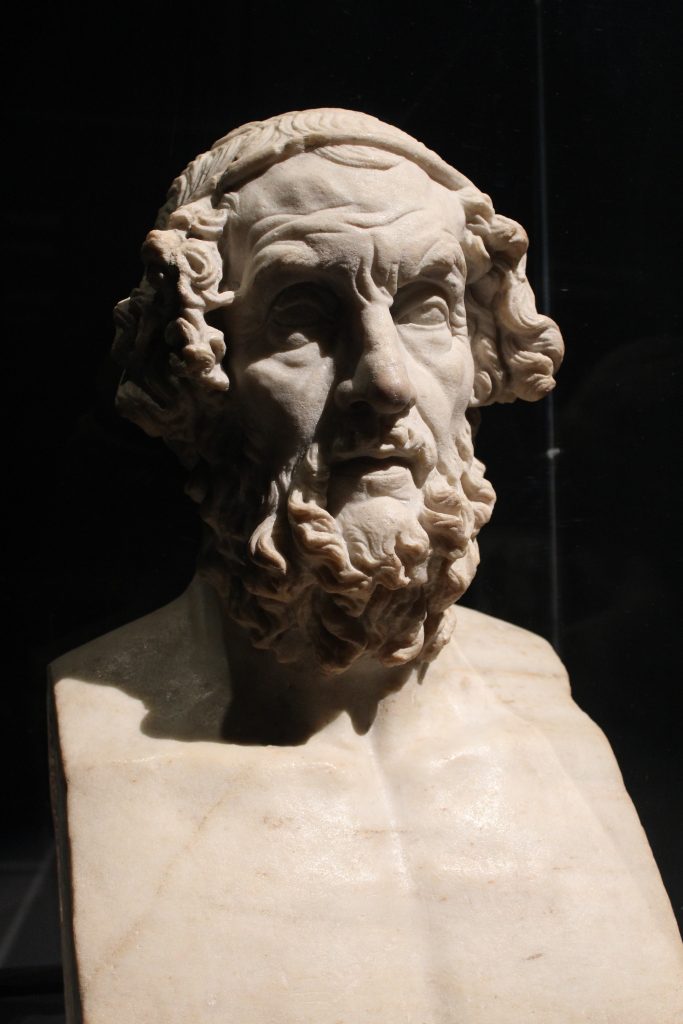

Portrait of Homer as a blind man 100-200 CE copy of an original dating 200-100 BCE, British Museum. Photo: Kosmos Society

__

Hélène Emeriaud is a Team member at HeroesX, a MOOC on edX. She studied ancient Greek at school in France and for several years at the University of Minnesota. She holds a degree in Education from Montreal University, and a Master of Education from McGill University. She is an active participant and member of the Editorial Team in the Kosmos Society with a particular interest in ancient Greek and Latin language learning.