A guest post by Safdar Mandviwala

Only a month ago I perused the exquisite Parthenon marbles at the New Acropolis Museum in Athens, together with the Harvard Center for Hellenic Studies study-group led by Professor Gregory Nagy. Arrayed to reflect the original placement of the marbles on the Parthenon Frieze[1], with the second floor of the museum oriented in perfect alignment with the aspect of the Parthenon, visible atop the adjacent Acropolis, the display is astounding. There are conspicuous gaps in the display; deliberate spaces to identify those marbles that were destroyed through violence and time and those that were taken away by foreigners, most notably the so-called ‘Elgin Marbles’[2] removed from the Parthenon by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, during 1801 to 1812. There has been much controversy and debate around where these marbles really belong.

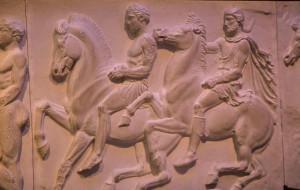

Now I stand before the marbles[3] at the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum, having had the opportunity to visit London with my family. The familiar feeling of awe at these sculptures and reliefs overcomes me, and my family witnesses an unusually ecstatic Dad prancing around the gallery as if riding one of the relief horses. The feeling is akin to the elation at finding the last piece in a jigsaw puzzle, multiplied over.

Now I stand before the marbles[3] at the Duveen Gallery in the British Museum, having had the opportunity to visit London with my family. The familiar feeling of awe at these sculptures and reliefs overcomes me, and my family witnesses an unusually ecstatic Dad prancing around the gallery as if riding one of the relief horses. The feeling is akin to the elation at finding the last piece in a jigsaw puzzle, multiplied over.

The museum houses the majority of the surviving Parthenon marbles and has chosen not to display gaps in the procession, but rather to separately showcase in an adjacent gallery the cast replicas commissioned by Lord Elgin on some marbles that were not acquired. It is claimed these replicas represent truly the original marbles more than the actual sculptures, recently removed from the Parthenon and now housed in the New Acropolis Museum, which have been badly damaged through exposure to the elements.

From the triangular pediments on either end of the long Duveen Gallery to the metopes arranged on each long side I witness familiar scenes. On the east pediment, which narrates the birth of Athena, the reclining figure of Dionysus with the imagined wine cup in hand, the waxing chariot of Helios to the left and the waning Selene horse on the right. Poseidon’s formidable torso and Athena’s bust on the west pediment are the highlights of their famous contest to be patron of Athens[4].

Along each side of the gallery: Centaurs in violent conflict with the Lapiths in the Centauromachy[5]; the calm procession which some say represents the contemporary Panathenaic Festival[6], others the founding myth of Athens, and others still the heroization of the 192 Athenians killed in the battle of Marathon (490 BCE in which the Athenians defeated the Persians against great odds); a boy (or girl?[7]) assisting an adult in folding a piece of cloth, understood to be the presentation of Athena’s peplos.

Along each side of the gallery: Centaurs in violent conflict with the Lapiths in the Centauromachy[5]; the calm procession which some say represents the contemporary Panathenaic Festival[6], others the founding myth of Athens, and others still the heroization of the 192 Athenians killed in the battle of Marathon (490 BCE in which the Athenians defeated the Persians against great odds); a boy (or girl?[7]) assisting an adult in folding a piece of cloth, understood to be the presentation of Athena’s peplos.

Reading some of the inscriptions posted near the marbles, I get a sense of the great debate regarding their removal from the Parthenon. Almost defensively they expound on the conservation of these treasures in the care of the British Museum. They also refer to their place among antiquities from other ancient civilizations that may have influenced the art-form and themes depicted in the reliefs. This reminds me of an interesting discussion about artifacts on the Hour 25 Forum hosted by Kevin McGrath which explores this debate in a wider context.

I feel quite privileged to have had the opportunity to see the majority of these antiquities in the space of one month, both in Athens and in London.

Alafia, my wife, reminds me that our twelve-year-old is eager to explore the Ancient Egypt section as he is currently reading Rick Riordan’s Kane Chronicles and wants to see Ra, Seth, Isis, Anubis, and their other gods, mummies and shabtis, not to mention the Rosetta Stone.

Like a child in a playground I implore: “Just five more minutes, please?”

Notes

[1] Link to Wikipedia article on the “Parthenon Frieze”.

[2] Link to Wikipedia article on the “Elgin Marbles”.

[3] The Museum’s preferred term is the Parthenon sculptures or, as carved on the wall of the Duveen Gallery, “The sculptures of the Parthenon.” Link to “Parthenon Sculptures: Facts and figures”, British Museum website.

[4] A retelling of this contest can be found in the page “Athena and Poseidon’s contest for Athens” on the website Athena: A Voyage with the Gods.

A selection of original sources are quoted in the section “Athena and Poseidon vie for Athens” on the Athena page at theoi.com.

[5] Link to Wikipedia article on the Lapiths, section on “Centauromachy”.

[6] Link to Wikipedia article on the “Panathenaic Games.”

[7] This figure is often said to be a boy owing to the roundness of the buttocks, but as pointed out very interestingly by Professor Nagy on the study-tour, roundness of buttocks in ancient Greek sculpture is no indication of sex—we have many examples of females with round buttocks, and much time was then spent in examining the buttocks of female sculptures to verify this assertion.

Photos: Safdar Mandviwala

Safdar Mandviwala lives in Dubai, originally from Pakistan, and is (or was) a career banker of 22 years. He is now in search of a new identity and first joined HeroesX v.4, after which he traveled with Professor Nagy who led the travel-study program to Greece in June 2016. With his new-found passion for ancient Greek literature, he plans to learn and participate on the Hour 25 Forums as much as possible.