Even by the look of him it was plain that he was a son of Zeus; for his body measured four cubits, and he flashed a gleam of fire from his eyes; and he did not miss, neither with the bow nor with the javelin.[1]

Apollodorus, among others, provides a number of stories about Hēraklēs in The Library (Book 2, chapters 4 and 5), and such stories provided inspiration for artworks from ancient Greece through to modern times.

Hēraklēs’ prowess was evident right from his birth: he killed snakes even when he was still a baby in the cradle.[2]

Gregory Nagy provides another episode of Hēraklēs’ life:

Hēraklēs was not only the founder of the Olympic Festival but was also a competitor in every athletic event of the first Olympics, and, even more, that he was the victor in each one of these events.[3]

Hēraklēs was a popular subject for tragedy. Euripides’ surviving drama Hēraklēs depicts how he kills his children in a fit of madness. You can find the tragedy in the Kosmos Text Library, and Gregory Nagy has written a commentary on Classical Inquiries.[4]

Other Greek plays included Sophocles’ Heracles and Trachiniae, plays by Spintharus and Diognees of Sinope; the Omphale of Ion, and of Achaeus (satyric plays); and Aeschylus, Euripides and Pamphilus (?) wrote on the Children of Heracles.[5]

Xenophon adapted an old story about the Choice of Hēraklēs, where the hero is approached by two women—one representing Pleasure and one Virtue.[6]

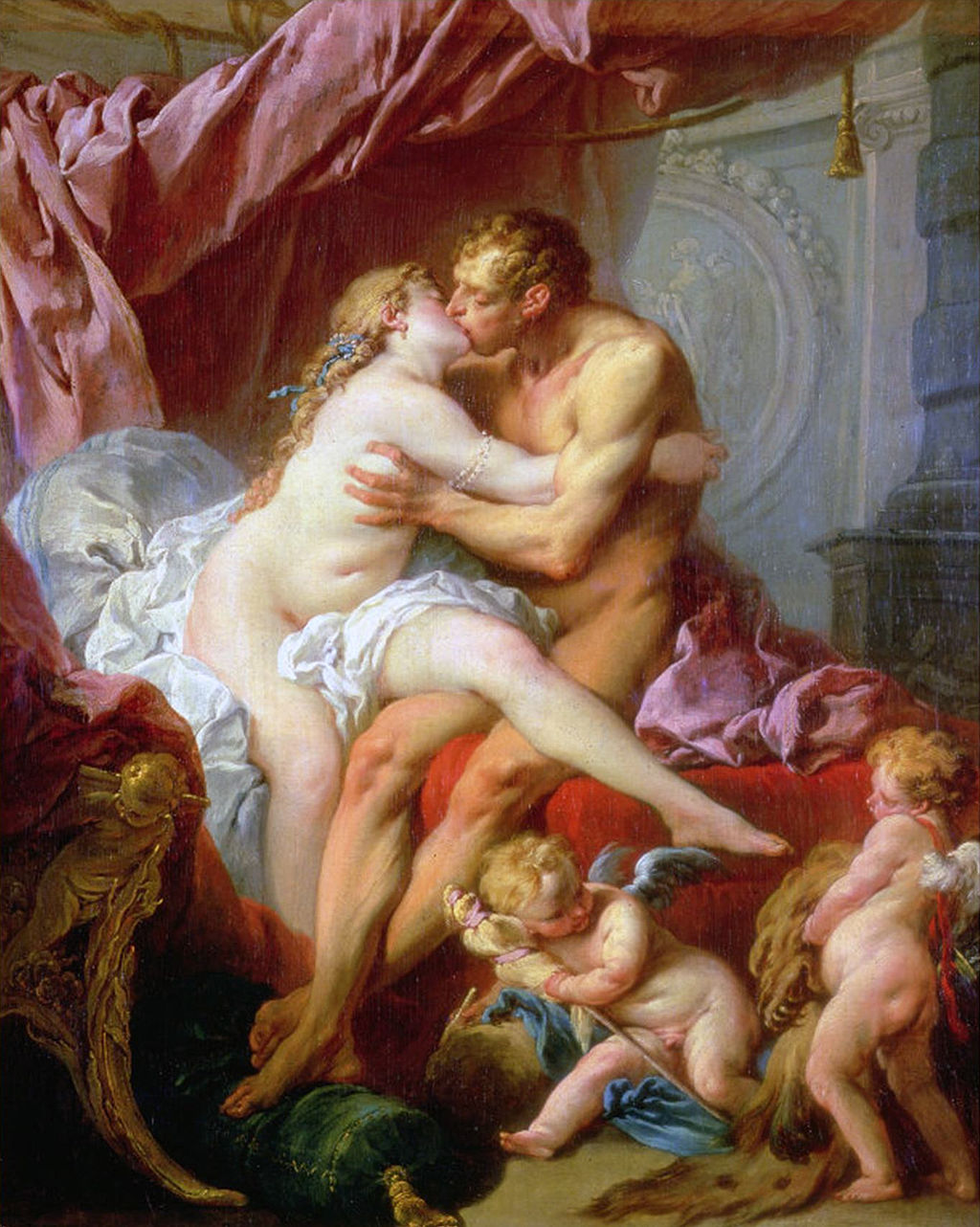

In another episode, Hēraklēs had to work for Omphale as a slave.[7]

Another popular subject in the visual arts was the death of Hēraklēs: he was sent a poisoned garment, and was in such agony he threw himself onto a pyre. However, he was then taken to Olympus and immortalized to live among the gods.[8]

The myths were also treated by Roman tragedians and by poets like Ovid.

In this Gallery we have chosen artworks inspired by the myths of Hēraklēs.

We invite members to share in the forum further images of Hēraklēs myths.

Notes

[1] Apollodorus, The Library, 2.4.9. translated by J.G. Frazer. 1921.

Online at Perseus

[2] Apollodorus, The Library 2.4.8. The story is also told elsewhere, for example in Pindar Nemean 1.

[3] Nagy, Gregory. 2019.09.06. “Thinking Comparatively about Greek mythology VII, Greek mythological models for prototyping Hēraklēs”. Classical Inquiries

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thinking-comparatively-about-greek-mythology-vii-greek-mythological-models-for-prototyping-herakles/

[4] Nagy, Gregory. 2018.04.20. “A sampling of comments on the Herakles of Euripides.” Classical Inquiries.

https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-the-herakles-of-euripides

[5] Wright, Matthew. 2016. The Lost Plays of Greek Tragedy, Volume 1. Bloomsbury, London. p204.

[6] Xenophon Memorabilia 2.21–2.33. You can find the story in the translation by E.C. Marchant, 1923.

Onine at Perseus

[7] Apollodorus The Library 2.6.3.

[8] Apollodorus The Library 2.7.7.

Image credits

Baby Herakles with the snake. Roman, 2nd century CE. Capitoline Museums

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Workshop of Peter Paul Rubens. c 1640. Young Hercules Killing a Snake

Photo: Dorotheum. public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

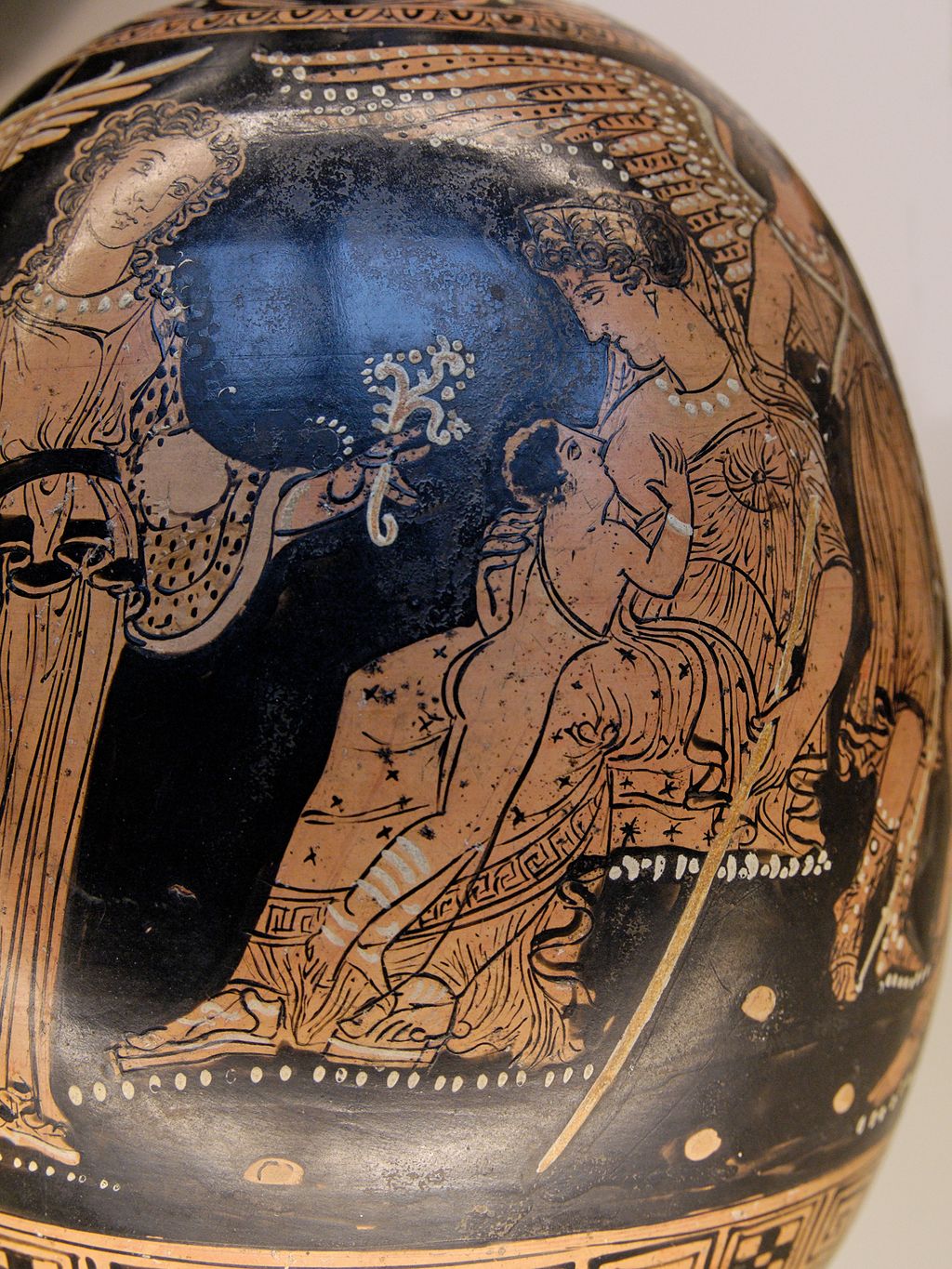

Hera suckling Herakles, c 360–350 BCE. British Museum.

Photo: Jastrow Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license. via Wikimedia Commons

Relief of Herakles, standing. Roman or Parthian, c 100–256 CE.

Public domain, via Yale University Art Gallery.

Statue of Herakles

Photo: Yale University Art Gallery. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

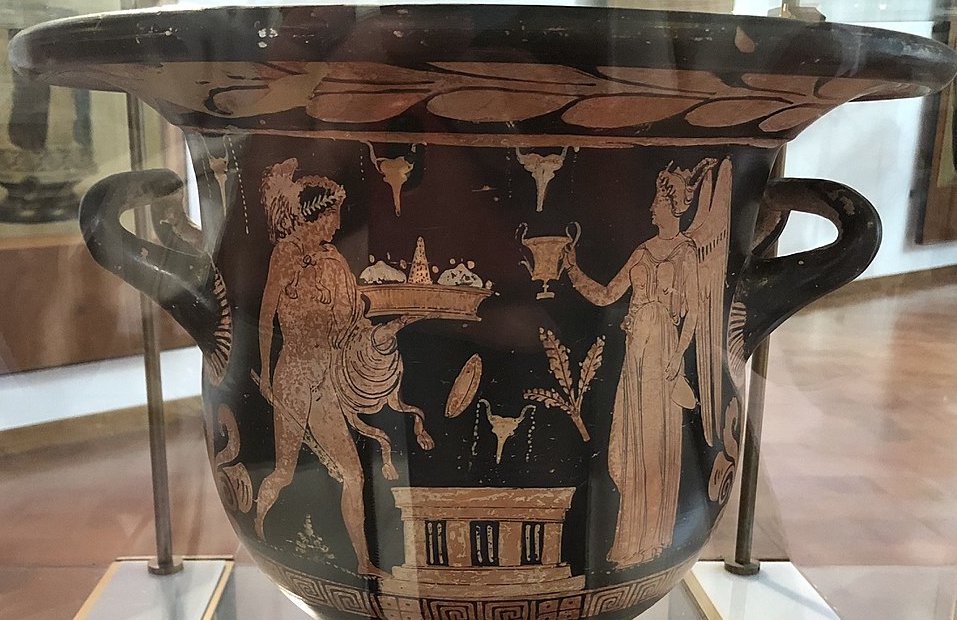

Herakles and Nike offering a sacrifice. Apulian krater. Musée d’Agrigente

Photo: Codex, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. via Wikimedia Commons

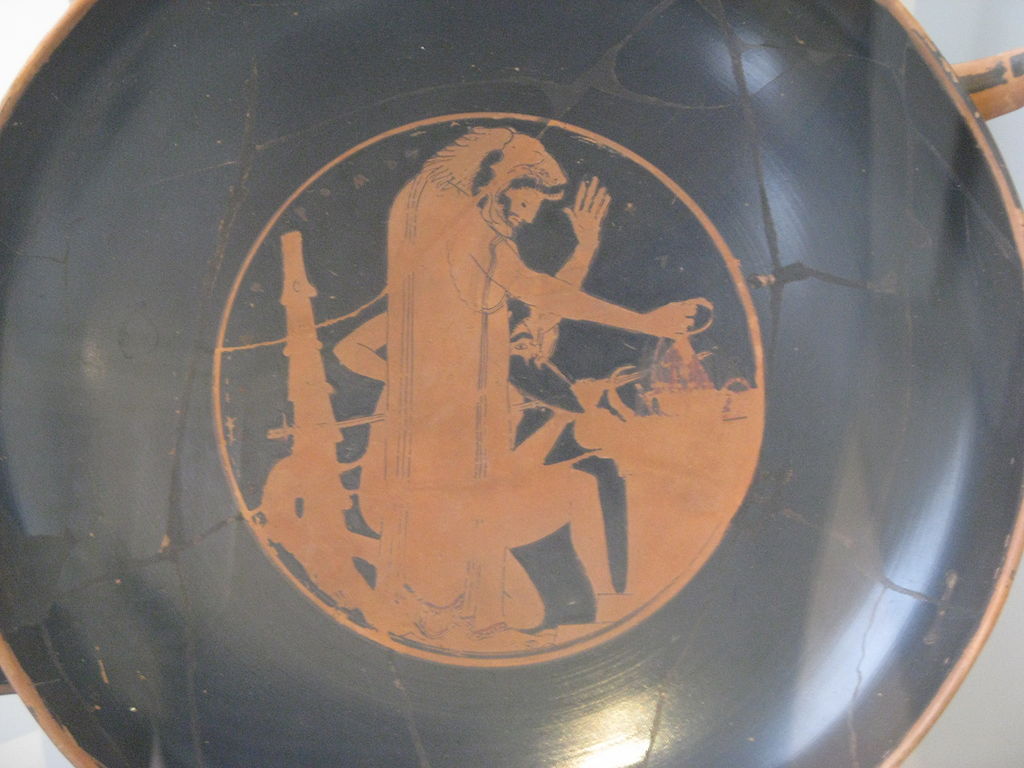

Heracles making an offering. Attic red-figure Kylix, c 510–500 BCE

Photo: Marcus Cyron, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. via Wikimedia Commons

Heracles. Red-figure krater. Archaeological Museum of Agrigento.

Photo: Zde, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. via Wikimedia Commons

Ferdinand-Victor-Eugène Delacroix. 1862. Hercules and Alcestis

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Heracles carrying off a woman. Bronze Etruscan mirror. 6th century CE.

From A.S. Murray Greek Bronzes, no known copyright restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Carving at Nemrut Dağ, of Commagene and Heracles

Photo: Verity Cridland Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. via Wikimedia Commons

Farnese Hercules. c 216 CE based on an original of 4th century BCE; partially restored. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples.

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen. Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license. via Wikimedia Commons.

Peter Paul Rubens: Hercules and Omphale. 1602–1605. Louvre.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

François Boucher: Hercules and Omphale. 1735. Pushkin Museum.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Annibale Carracci: The Choice of Heracles. 1595. Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Auguste Couder. The Earth, or the Fight of Heracles and Antaeus. 1819. Louvre.

Photo: Jastrow. Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license. via Wikimedia Commons

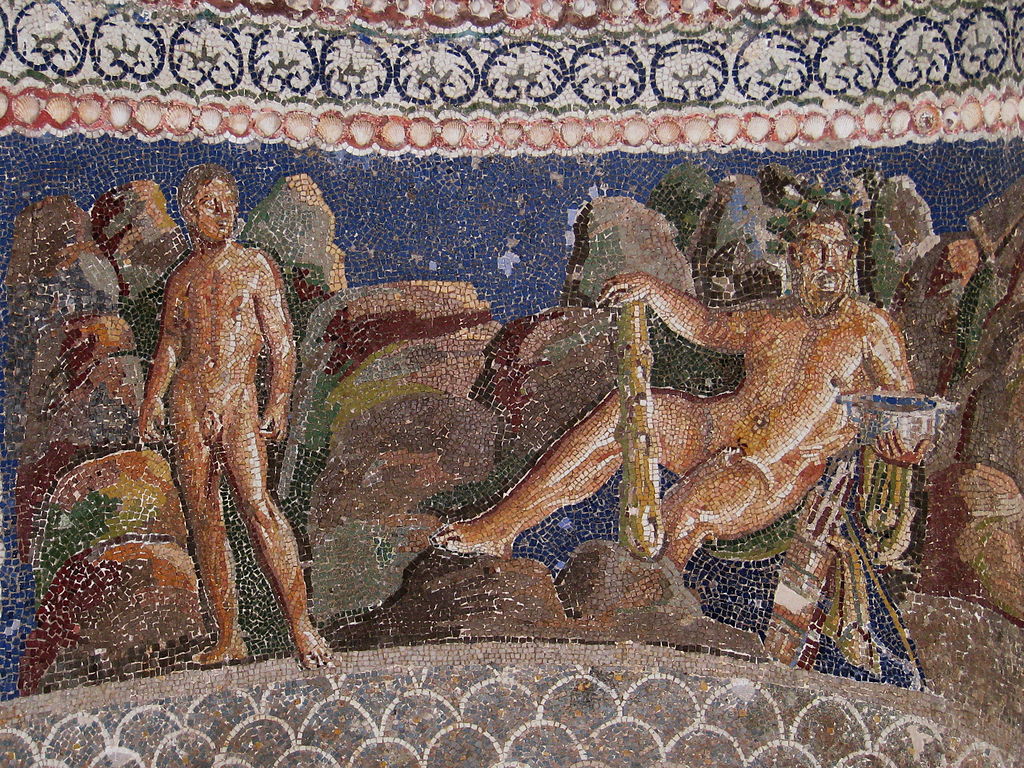

Hercules and Iolaus. Mosaic. Anzio Nymphaeum. Museo Nazionale Romana.

Haiduc. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Louis-Jean-François Lagrenée: The Abduction of Deianeira by the Centaur Nessus. 1755. Louvre.

Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Plate with Hercules, Nessus, and Deianira, 1525–1535. The Walters Art Museum

Creative Commons CC0 License.

Giambologna: Hercules beating the centaur Nessus. Loggia dei Lanzi.

Photo: Yair Haklai. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.5 Generic license. via Wikimedia Commons

Samuel Morse. c 1812. Dying Hercules

Photo: Yale University Art Gallery. public domain via Wikimedia Commons

François Lemoyne: The Apotheosis of Hercules. 1731–1736. Palace of Versailles.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images and online texts accessed December 2019.

___

Hélène Emeriaud, Janet Ozsolak, and Sarah Scott are members of Kosmos Society.