What is the role played by fathers and sons in ancient Greek epic and lyric? Are fathers good role models? Do they show or teach their children how to behave or function? What kind of relationships do we witness in the texts? Are immortal and mortal fathers portrayed in similar ways?

A strong link seems to bond fathers and sons.

Of course, the relationship between gods and their sons is very peculiar.

As shown in Hesiod’s Theogony, among the gods fathers and sons were violent with each other. Kronos castrated his own father, Ouranos, and after that, since he was himself afraid of all his children—boys and girls—he did not allow them to live in the outside world, so ate them. Zeus, the youngest son, was able to change the situation and his brothers and sisters were born again, and he took control over his father.

As shown in Hesiod’s Theogony, among the gods fathers and sons were violent with each other. Kronos castrated his own father, Ouranos, and after that, since he was himself afraid of all his children—boys and girls—he did not allow them to live in the outside world, so ate them. Zeus, the youngest son, was able to change the situation and his brothers and sisters were born again, and he took control over his father.

Quickly then throve the spirit and beauteous limbs of the king, and, as years came round, having been beguiled by the wise counsels of Earth 495 huge Kronos, wily counselor, let loose again his offspring, having been conquered by the arts and strength of his son.

Theogony 492–496, Sourcebook[1]

So these gods do not provide the best role model for a healthy bond between father and son.

One of the epithets of Zeus is “father Zeus”. He fathered a number of other gods, and very many mortals.

He was moved by the death of his mortal son Sarpedon, and helped protect his body:

The son of scheming Kronos looked down upon them in pity and said to Hera who was his wife and sister, “Alas, that it should be the lot of Sarpedon whom I love so dearly to perish by the hand of Patroklos. [435] I am in two minds whether to catch him up out of the fight and set him down safe and sound in the fertile district [dēmos] of Lycia, or to let him now fall by the hand of the son of Menoitios.”

…

[665] Then Zeus lord of the storm-cloud said to Apollo, “Dear Phoebus, go, I pray you, and take Sarpedon out of range of the weapons; cleanse the black blood from off him, and then bear him a long way off where you may wash him in the river, anoint him with ambrosia, [670] and clothe him in immortal raiment; this done, commit him to the arms of the two fleet messengers, Death, and Sleep, who will carry him straightway to the fertile district [dēmos] of Lycia, 674 and there his relatives and comrades will ritually prepare [tarkhuein] him, [675] with a tomb and a stele—for that is the privilege of the dead.”

Iliad 16.431–437, 16.665–675, Sourcebook

However, he violently scolded Arēs, one of his immortal sons.

Zeus looked angrily at him [= Arēs] and said, “Do not come whining here, you who face both ways. [890] I hate you worst of all the gods in Olympus, for you are ever fighting and making mischief. You have the intolerable and stubborn spirit of your mother Hera: it is all I can do to manage her, and it is her doing that you are now in this plight: [895] still, I cannot let you remain longer in such great pain; you are my own off-spring, and it was by me that your mother conceived you; if, however, you had been the son of any other god, you are so destructive that by this time you should have been lying lower than the Titans.”

He then bade Paieon heal him.

Iliad 5.889–900, Sourcebook

As for mortal fathers in Homeric poetry, we have examples where they give advice to their sons.

We see the same line in in Iliad 6.207–208 and in Iliad 11.784, a statement of heroic code. Here is Glaukos’ account of what his father told him:

Ἱππόλοχος δέ μ᾽ ἔτικτε, καὶ ἐκ τοῦ φημι γενέσθαι:

πέμπε δέ μ᾽ ἐς Τροίην, καί μοι μάλα πόλλ᾽ ἐπέτελλεν

αἰὲν ἀριστεύειν καὶ ὑπείροχον ἔμμεναι ἄλλων,

μηδὲ γένος πατέρων αἰσχυνέμεν, οἳ μέγ᾽ ἄριστοι

210 ἔν τ᾽ Ἐφύρῃ ἐγένοντο καὶ ἐν Λυκίῃ εὐρείῃ.

ταύτης τοι γενεῆς τε καὶ αἵματος εὔχομαι εἶναι.Hippolokhos was father to myself, and when he sent me to Troy he urged me again and again to fight ever among the foremost and outcompete my peers, so as not to shame the blood of my fathers [210] who were the noblest in Ephyra and in all Lycia. This, then, is the descent I claim.

Iliad 6.206–211, Sourcebook

Peleus gives the same advice to his son Achilles:

…τὼ δ᾽ ἄμφω πόλλ᾽ ἐπέτελλον

Πηλεὺς μὲν ᾧ παιδὶ γέρων ἐπέτελλ᾽ Ἀχιλῆϊ

αἰὲν ἀριστεύειν καὶ ὑπείροχον ἔμμεναι ἄλλων[2]I said my say and urged both of you to join us. You were ready enough to do so, and the two old men charged you much and strongly. Old Peleus bade his son Achilles fight ever among the foremost and outcompete his peers

Iliad 11.781–784, Sourcebook

On the other hand the advice given to Patroklos by his father is perhaps more suited to his role as the therapōn: of Achilles

…while Menoitios, the son of Aktor, spoke thus to you: [785] ‘My son,’ said he, ‘Achilles is of nobler birth than you are. 787 You are older; but he is much better in force [bíē]. Counsel him wisely, guide him in the right way, and he will follow you to his own profit.’

Iliad 11.785–789, Sourcebook

Perhaps the best known example of advice from a father to a son from HeroesX is when Nestor speaks to his son before the chariot race:

Fourth in order Antilokhos, son to noble Nestor, son of high-hearted Neleus, made ready his horses. These were bred in Pylos, and his father came up to him [305] to give him good advice of which, however, he stood in but little need. “Antilokhos,” said Nestor, “you are young, but Zeus and Poseidon have loved you well, and have made you an excellent charioteer. I need not therefore say much by way of instruction. You are skillful at wheeling your horses round the post, [310] but the horses themselves are very slow, and it is this that will, I fear, mar your chances. The other drivers know less than you do, but their horses are fleeter; 313 Come, my philos, put in your thūmos every sort of skill [mētis], 314 so that prizes may not elude you. [315] It is with mētis rather than force [biē] that a woodcutter is better. 316 It is with mētis that a helmsman over the wine-dark sea [pontos] 317 steers his swift ship buffeted by winds. 318 It is with mētis that charioteer is better than charioteer. [320] If a man go wide in rounding this way and that, whereas a man of craft [kerdos] may have worse horses, but he will keep them well in hand when he sees the turning-post [terma]; he knows the precise moment [325] at which to pull the rein, and keeps his eye well on the man in front of him. 326 I [= Nestor] will tell you [= Antilokhos] a sign [sēma], a very clear one, which will not get lost in your thinking. 327 Standing over there is a stump of deadwood, a good reach above ground level. 328 It had been either an oak or a pine. And it hasn’t rotted away from the rains. 329 There are two white rocks propped against either side of it. [330] There it is, standing at a point where two roadways meet, and it has a smooth track on both sides of it for driving a chariot. 331 It is either the tomb [sēma] of some mortal who died a long time ago 332 or was a turning point [nussa] in the times of earlier men. 333 Now swift-footed radiant Achilles has set it up as a turning point [terma plural]. 334 Get as close to it as you can when you drive your chariot horses toward it, [335] and keep leaning toward one side as you stand on the platform of your well-built chariot, 336 leaning to the left as you drive your horses. Your right-side horse 337 you must goad, calling out to it, and give that horse some slack as you hold its reins, 338 while you make your left-side horse get as close as possible [to the turning point], 339 so that the hub will seem to be almost grazing the post [340]—the hub of your well-made chariot wheel. But be careful not to touch the stone [of the turning point], 341 or else you will get your horses hurt badly and break your chariot in pieces. 342 That would make other people happy, but for you it would be a shame, 343 yes it would. So, near and dear [philos] as you are to me, you must be sound in your thinking and be careful, for if you can be first to round the post [345] there is no chance of any one giving you the go-by later, not even though he had Arion, the horse of Adrastos, a horse which is of divine race, or the horses of Laomedon, which are the noblest in this land.”

Iliad 23.301–349, Sourcebook

This loving speech provides good guidance not only for the race in hand but for life overall.

We see in epic an example of a father doing the most extreme action on behalf of his son when Priam risks everything to face Achilles, who has killed and degraded the body of his son Hector. in Iliad 24 and “Tall King Priam entered …, and going right up to Achilles he clasped his knees and kissed the dread man-slaughtering hands that had slain so many of his sons.”

When Odysseus reveals himself to Laertes, part of the proof involves how his father had given guidance about the orchard:

When Odysseus reveals himself to Laertes, part of the proof involves how his father had given guidance about the orchard:

I will point out to you the trees in the vineyard which you gave me, and I asked you all about them as I followed you round the garden. We went over them all, and you told me their names and what they all [340] were. You gave me thirteen pear trees, ten apple trees, and forty fig trees; you also said you would give me fifty rows of vines; there was wheat planted between each row, and they yield grapes of every kind when the seasons [hōrai] of Zeus have been laid heavy upon them

Odyssey 24.336–344, Sourcebook

Lineage is important as we see when heroes boast about their fathers or earlier ancestors.

Going back generations shows the strength of the family

Then said Diomedes, [110] “Such an one is at hand; he is not far to seek, if you will listen to me and not resent my speaking though I am younger than any of you. I am by lineage son to a noble sire, Tydeus, who lies buried at Thebes. [115] For Portheus had three noble sons, two of whom, Agrios and Melas, abode in Pleuron and rocky Calydon. The third was the horseman Oeneus, my father’s father, and he was the most valorous of them all. Oeneus remained in his own country, but my father (as Zeus and the other gods ordained it) [120] migrated to Argos. He married into the family of Adrastos, and his house was one of great abundance, for he had large estates of fertile grain-growing land, with much orchard ground as well, and he had many sheep; moreover he excelled all the Argives in the use of the spear. ”

Iliad 14.109–125, Sourcebook

In this Ode by Pindar, a dead father, Amphiaraus, is communicating with his living son, the hero Alcmaeon. Amphiarus is one of the warriors in the War of the Seven Against Thebes and his son Alcmaeon is one of the Epigonoi. The Seven against Thebes failed but their sons the Epigonoi were successful. So, Pindar says, sons materialize what their fathers dreamed of achieving.

In this Ode by Pindar, a dead father, Amphiaraus, is communicating with his living son, the hero Alcmaeon. Amphiarus is one of the warriors in the War of the Seven Against Thebes and his son Alcmaeon is one of the Epigonoi. The Seven against Thebes failed but their sons the Epigonoi were successful. So, Pindar says, sons materialize what their fathers dreamed of achieving.

By inherited nature, the noble purpose [lēma] shines forth from fathers [pateres] to sons.

Pindar’s Pythian 8

Translation and Notes by Gregory Nagy, as of 2018.02.07

What passages from the epics or lyric about fathers and sons—mortal or immortal—demonstrate positive or negative role models or relationships? How do they fathers and sons speak to or about each other?

Please join us in the forum to share and discuss further passages.

References

[1] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[2] Iliad Greek text from: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Online at Perseus

Texts accessed June 2018.

Image credits

Medousa (photo) Statue of Kronos Hesperidengarten, Nürnberg (artist not stated), Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

Sailko (photo) Henri Lévy Sarpedon, 1874, Musée d’Orsay. Creative Commons CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Marie-Lan Nguyen (photo) Manner of Princeton Painter: Warrior’s Departure Attic black-figure amphora, circa 550–540BCE. Louvre Museum. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Lady Erin (photo) Ulysses embracing Laertes, Sarcophagus fragment, mid 2nd century CE, Museo Barracco, Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 2.0, via flickriver

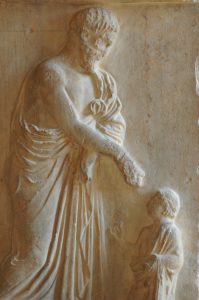

Jastrow (photo) Dead man leaving his son, funeral stele, Pentelic marble circa 410–400 BCE, Louvre. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website. Images accessed June 2018.

______

Hélène Emeriaud, Janet Ozsolak, and Sarah Scott are members of the Kosmos Society.