“A World of Emotions: Ancient Greece, 700 BC–200 AD”

Onassis Cultural Center New York

Onassis Foundation USA, 645 5th Ave., New York

Through June 24, 2017

A guest post by David A. Beardsley

Much of my own ongoing fascination with the ancient Greeks is in that theirs is the first culture with which I can readily connect, and this is largely because of the way they display their emotions. The legacy they left—the myths, the philosophy, the artworks—still inspire me and many others today in part because of the emotions they contain, and with which many of us moderns can still identify. They have a universal quality that speaks across the ages and races. In the catalog notes, Angelos Chaniotis recounts this scene from Homer’s Iliad:

In Book 24, Priam approaches Achilles, who has killed his son Hector, in order to request the delivery of Hector’s mutilated body for burial. How can Priam persuade the man, who in his grief and rage for the death of Patroklos had bound Hector’s body behind his chariot and dragged it around the walls of Troy? Priam kneels in front of Achilles, kisses the hand that had killed several of his sons and relatives, and says three words: mnesai patros soio, “Think of your father.” Three words break the unbreakable warrior. They create an emotional bond between the enemies by reminding them of what unites them: humanity. Thinking of his own aged father, who will sometime mourn, like Priam, the death of a son, Achilles cannot resist the older man’s request. United in grief, one for the death of a son, the other for the loss of a friend, but above all united by a common humanity, the Trojan king and the Greek hero weep together.

The Greeks knew their feelings well enough to make gods of them, some of whose names have come down to us in English: Phobos, Eros, Hedone, Mania, etc. This objectification of emotions is something that I feel we moderns can still learn from: rather than just being victims of our feelings, we can observe them and embrace them.

For this reason, I highly recommend that you make your way to the Onassis Cultural Center (Onassis Foundation USA headquarters) at 645 5th Avenue in New York, which is running an exhibit called “A World of Emotion: Ancient Greece 700BC–200AD,” through June 24, 2017. It brings together works of high art and emotion, such as the full-sized statue of Eros stringing his bow (Figure 1), as well as everyday items such as defixioi (curse tablets)—lead sheets with imprecations written on them, pierced by a nail, made by the internet trolls of their day. Along the way there are theater masks, funerary steles, kraters, vases, ostrakons, and offerings to gods and goddesses, all illustrating some aspect of their owners’ emotional world: happiness/sadness, love/hate, revenge/forgiveness, mourning/joy, frustration/fulfillment. They resonated with me in a way that few artifacts from the ancient world ever have.

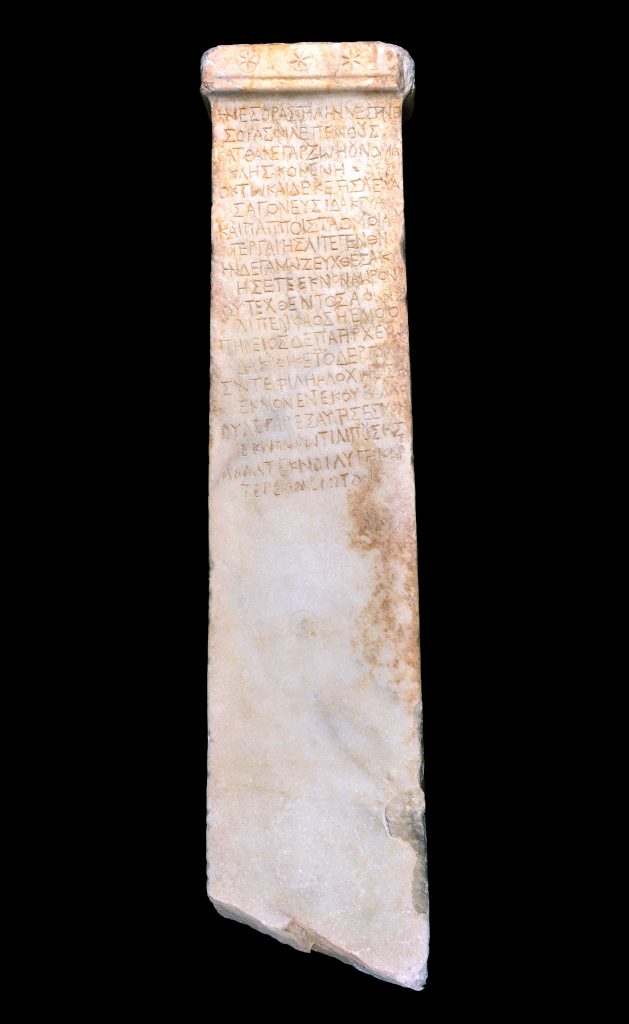

One of the most poignant was a funeral stele (Figure 2), all in writing, which tells the sad story of 18 year-old Zoe (“Life”) dying in childbirth along with her premature baby, who “left the sunlight behind without ever crying.” She was her parents’ only child, so they lost all chance for any grandchildren. The inscription on the stele starts out measured and regular, but by the end the writing has become uneven and erratic, written as if by a person who has been overwhelmed by grief. According to program notes from the exhibition, the stele was set up by Zoe’s father and mother, who in the words themselves and the inscription of them, have left behind a timeless record of their terrible loss.

Then compare this with a stele (Figure 3) for a “loveable pig,” whose abbreviated story suggests only that it died prematurely after being run over by its owner’s cart, depicted on the stele. As one who has lost several pets in my lifetime, I understand the sense of grief, but also the affection and wit that underlies this remembrance.

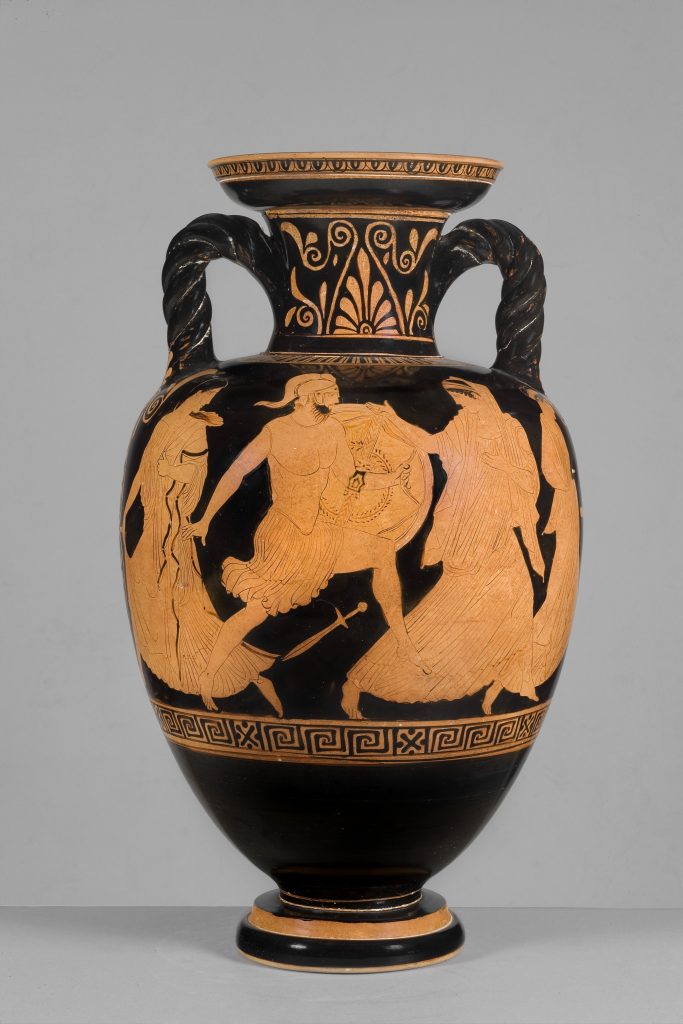

Many works, presumably like that of the pig, seem to have been commissioned in order to remember or commemorate a person or event. I gained a new appreciation for the art of pottery, which can show one thing on the inside of, say, a krater, and something else on the outside. As one who is sensitive to metaphor, I liked that some of the pots would display a mythological scene on one face and a personal, homebody scene on another. For example, one (Figure 4) showed a scene of Menelaus chasing after his wife Helen, who many assumed he would want to kill for leaving him, but instead he forgives her and takes her back to Sparta. This was contrasted on the other side with a farewell scene of a family preparing for the departure of a son—giving, I think, the metaphorical message that he too will always be welcome back into the family.

Another example of a metaphor, quoted by Chaniotis in his notes, recounts the words of another Athenian who died too young:

Paramonos, son of Euhodos, from Piraeus, Athenian ephebe. Having felt joy together with many others many times in my few years, I lie here below, struck by deep sleep. Occupying a place among the stars together with Kastor and Pollux, I am a new Theseus.

The works themselves are collected from a wide geographical range and across nearly a millennium, so the collection is not representative of the Greek world—as if anything could be. No doubt there are some that are more erotic, more pathetic, more joyful than the ones shown here. A good many of them display what might be thought of as “bad behavior”—stealing the Palladium at Troy, the rape of Kassandra by Ajax, the murder of Agamemnon. But just being in their presence, knowing that they were created by other human beings although several thousand years ago, filled me with a new appreciation and love of my fellow humans. Even the ones who wrote curses.

There are just too many artworks to report on all of them, or to to speak to all the emotions of the creators. It seems a shame that with all the work—and the love—that obviously went into this show that it will last only a short time. It seems worthy of a permanent home somewhere. But these flowerings are rare, so try to get yourself to New York, and thank the creators of these magical works.

Image credits

Published with permission from the Onassis Foundation, as listed below.

Figure 1: Eros stringing his Bow, Marble, 2nd century AD, Musée du Louvre, MA 448 (MR 139). Photo: Hervé Lewandowski ©RMN-Grand Palais/ Art Resource, NY

Figure 2: Funerary Stele with Epigram for Zoe, daughter of Peneios, Marble, 3rd Century AD, Larissa, Diachronic Museum © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund

Figure 3: Funerary Stele for a Lovable Pig, Victim of a Traffic Accident, 2nd–3rd century AD, Marble, Ephorate of Antiquities of Pella, ΑΚΑ 1674 © Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports – Archaeological Receipts Fund. Photography: Orestis Kourakis

Figure 4: Neck-Amphora with Menelaos and Helen, attributed to the Kleophon Painter, 430–420 BC, Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig, LU 57 © Antikenmuseum Basel und Sammlung Ludwig