There is nothing sweeter than to fly [petesthai].

Aristophanes Birds 1343

Flying has often been one of our challenges as humans. We like to watch birds fly and we have been trying to copy them. And in myth gods and other entities are able to fly. Here are some passages from the ancient world about flight that is not by birds.

The chorus in Hippolytus as Phaedra enters the scene beautifully expresses the desire to fly shared by so many people.

Chorus

732 Oh if only I could be down under the steep heights in deep cavernous spaces, 733 where I could become a winged [pteroeis] bird 734 —a god would make me into that, and I would become one of a whole flock of birds in flight [potanos], yes, a god would make me that. 735 And if only I could then lift off in flight [areîn] and fly away, soaring over the waves of the sea [pontos] 736 marked by the Adriatic 737 headland, and then over the waters of the river Eridanos 738 where into the purple swirl comes 739 a cascade from unhappy 740 girls in their grief for Phaethon—a cascade of tears that pour down 741 their amber radiance.Euripides Hippolytus 732–741, adapted from Sourcebook

Then we have failed attempts; one is reported by Ovid with the amazing myth of Daedalus and his son Icarus.

So saying he applied his thought to new invention and altered the natural order of things. He laid down lines of feathers [penna], beginning with the smallest, following the shorter with longer ones, so that you might think they had grown like that, on a slant. In that way, long ago, the rustic pan-pipes were graduated, with lengthening reeds. Then he fastened them together with thread at the middle, and bees’-wax at the base, and, when he had arranged them, he flexed each one into a gentle curve, so that they imitated real bird’s wings [āla]. His son, Icarus, stood next to him, and, not realising that he was handling things that would endanger him, caught laughingly at the down [plūma] that blew in the passing breeze, and softened the yellow bees’-wax with his thumb, and, in his play, hindered his father’s marvellous work…”

Ovid Metamorphoses Book VIII 188–200, adapted from translation by A. S. Kline

Of course Icarus did not listen to his father’s instructions, his wings melted, and he fell and died. The place where he fell is named the Icarian sea after him.

There is another myth, told by Apollodorus: the story of Phrixos and his sister Helle who fly away on a ram, but Helle falls into the sea; just like Icarus she is commemorated in the name of the place where she falls. Presumably the ram had some form of flying ability, although there is no mention of wings:

Of the sons of Aeolus, Athamas ruled over Boeotia and begat a son Phrixus and a daughter Helle by Nephele. And he married a second wife, Ino, by whom he had Learchus and Melicertes. But Ino plotted against the children of Nephele and persuaded the women to parch the wheat; and having got the wheat they did so without the knowledge of the men. But the earth, being sown with parched wheat, did not yield its annual crops; so Athamas sent to Delphi to inquire how he might be delivered from the dearth. Now Ino persuaded the messengers to say it was foretold that the infertility would cease if Phrixus were sacrificed to Zeus. When Athamas heard that, he was forced by the inhabitants of the land to bring Phrixus to the altar. But Nephele caught him and her daughter up and gave them a ram with a golden fleece, which she had received from Hermes, and borne [pherein] through the sky [ouranos] by the ram they crossed land and sea. But when they were over the sea which lies betwixt Sigeum and the Chersonese, Helle slipped into the deep and was drowned, and the sea was called Hellespont after her.

Apollodorus, Library 1.9.1, adapted from translation by Sir James George Frazer

In Homeric epic even words can be winged [pteroeis].

We also have gods and goddesses flying, or at least they seem to move from Olympus to earth and back.

Iris can fly as messenger to and from Olympus. Vase paintings show her with wings on her back, and in Homeric poetry she is also described in terms that indicate her speed and motion, for example.

But father Zeus when he saw them from Ida was very angry, and sent golden-winged [khrusopteros] Iris with a message to them. … With this storm-footed [aellopos] Iris sprang up, [410] and went her way from the heights of Ida to the lofty summits of Olympus.

Iliad 8.397–398, 409–410, adapted from Sourcebook

Hermes, however, makes use of his famous winged sandals:

[340] Right then and there he [=Hermes] bound on his glittering golden sandals which bore [pherein] him like the wind [pnoiē] over land and sea; he took the wand with which he seals men’s eyes in sleep, or wakes them just as he pleases, [345] and flew [petasthai] holding it in his hand till he came to Troy and to the Hellespont.

Iliad 24.340–345, adapted from Sourcebook

The sun (Helios) in his chariot drawn by four winged horses. Red-figured alyx-krater c 430 BCE.

© The Trustees of the British MuseumSome gods do not have wings, but have chariots driven by flying horses according to texts and in the visual arts. Here is one example from the Iliad:

Arēs gave her [=Aphrodite] his gold-bedizened steeds. She mounted the chariot sick and sorry at heart, [365] while Iris sat beside her and took the reins in her hand. She lashed the horses on and they flew [petasthai] forward nothing loath, till in a trice they were at high Olympus, where the gods have their dwelling.

Iliad 5.363–367, adapted from Sourcebook

Another famous flying winged horse is Pegasus with his amazing myth. According to Hesiod,

280 From her [=[Medusa] too when, as the tale is, Perseus had cut off the head, up sprang huge Khrysaor and the steed Pegasus. To the latter came his name because he was born near the springs of Okeanos, while the other had a golden sword in his hands. And he indeed, winging his flight away [apo-petomai], left Earth, the mother of flocks, 285 and came to the immortals; in Zeus’s house he dwells, bearing [pherein] to counselor Zeus thunder and lightning.

Hesiod Theogony 280–286 adapted from Sourcebook

Bellerophon, son of Glaukos, son of Sisyphus was ordered to kill the Chimera. Then Bellerophon with the help of this horse equipped with wings was able to fly and kill the Chimera from above.

So Bellerophon mounted [ana–bibazein] his winged [ptēnos] steed Pegasus, offspring of Medusa and Poseidon, and soaring [airein] on high [hupsos] shot down the Chimera from the height.

Apollodorus Library 2.3.2, adapted from translation by James George Frazer

More about Bellerophon’s way of taming the flying Pegasus is told by Pindar.

And so mighty Bellerophon eagerly [85] stretched the gentle charmed bridle around its jaws and caught the winged [pteroeis] horse. Mounted [ana-bainein] on its back and armored in bronze, at once he began to play with weapons. And with Pegasus, from the chilly bosom of the lonely air [aithēr] he once attacked the Amazons, the female army of archers, [90] and he killed the fire-breathing Chimaera, and the Solymi. I shall pass over his death in silence; but Pegasus has found his shelter in the ancient stables of Zeus in Olympus

Pindar Olympian 13 For Xenophon of Corinth Foot Race and Pentathlon 464 BCE, adapted from translation by Diane Arnson Svarlien

The soul is sometimes depicted as a butterfly in the visual arts. But Plato describes the soul in terms of a chariot driven by flying horses:

We will liken the soul to the composite nature of a pair of winged [hupo-pteros] horses and a charioteer. Now the horses and charioteers of the gods are all good and [246b] of good descent, but those of other races are mixed; and first the charioteer of the human soul drives a pair, and secondly one of the horses is noble and of noble breed, but the other quite the opposite in breed and character. Therefore in our case the driving is necessarily difficult and troublesome.

…

we will now consider the reason why the soul loses its wings [pteron]. It is something like this. The natural function of the wing [pteron] is to soar upwards and carry up [meteōrizein] that which is heavy to the place where dwells the race of the gods. More than any other thing that pertains to the body [246e] it partakes of the nature of the divine. But the divine is beauty, wisdom, goodness, and all such qualities; by these then the wings [ptérōma] of the soul are nourished and grow, but by the opposite qualities, such as vileness and evil, they are wasted away and destroyed. Now the great leader in heaven, Zeus, driving a winged [ptēnos] chariot, goes first, arranging all things and caring for all things.Plato Phaedrus 246, adapted from translation by Harold N. Fowler

In the play Eumenides, you might be struck by a flying snake.

Apollo

Out of my temple at once, I order you. 180 Be gone, quit my sanctuary of the seer’s [mantis] art, or else you might be struck by a flying, winged [ptēnos], glistening snake shot forth from a golden bow-string, and then you would spit out black foam from your lungs in pain, vomiting the clotted blood you have drawn.Aeschylus Eumenides 178–184, Sourcebook

Apollo’s winged snakes are deadly, and also scary are the winged snakes in Arabia according to Herodotus:

2.75.1 There is a place in Arabia not far from the town of Buto where I went to learn about the winged [pterōtos] serpents. … 2.75.3 Winged [pterōtos] serpents are said to fly [ptesthai] from Arabia at the beginning of spring, making for Egypt; but the ibis birds encounter the invaders in this pass and kill them.

…

3.107.2 They [=Arabians] gather frankincense by burning that storax which Phoenicians carry to Hellas; they burn this and so get the frankincense; for the spice-bearing trees are guarded by small winged [hupo-pteros] snakes of varied color, many around each tree; these are the snakes that attack Egypt. Nothing except the smoke of storax will drive them away from the trees.

3.108.1 The Arabians also say that the whole country would be full of these snakes if the same thing did not occur among them that I believe occurs among vipers. … 109.1 if the vipers and the winged [hupo-pteros] serpents of Arabia were born in the natural manner of serpents life would be impossible for men; but as it is, when they copulate, while the male is in the act of procreation and as soon as he has ejaculated his seed, the female seizes him by the neck, and does not let go until she has bitten through. 109.2 The male dies in the way described, but the female suffers in return for the male the following punishment: avenging their father, the young while they are still within the womb gnaw at their mother and eating through her bowels thus make their way out. 109.3 …The Arabian winged [hupo-pteros] serpents do indeed seem to be numerous; but that is because (although there are vipers in every land) these are all in Arabia and are found nowhere else.Herodotus Histories 2.75.1–3, 3.107.2–109.3, adapted from translation by A.D. Godley

These are just a few examples of creatures and gods that fly but are not birds. We invite you to join in the Forum to share any other passages or images you have come across, whether in the visual or verbal arts.

Selected vocabulary

Greek terms

Definitions based on LSJ

aellópos [ἀελλό – πος] adj. storm-footed

airein [αἴρω] to raise, lift up

aithēr [αἰθήρ , αἰθέρος, ὁ] ether, heaven, air

anabaínein [ἀναβαίνω] to mount, to go up

anabibázein [ἀναβιβάζω] to cause to mount, uplift

apo-pétomai [ἀπο-πέτομαι] to fly off, fly away

hupópteros [ὑπόπτερος, ὑπόπτερον] adj. winged; soaring

húpsos [ὕψος , εος, τό] height; summit

khrusó-pteros [χρυσό-πτερος, χρυσό-πτερον] adj. golden-winged

meteōrízein [μετεωρίζω] to raise, lift up

ouranós [οὐρανός, οὐρανοῦ, ὁ] heaven, sky

pétasthai / pétesthai [πέτομαι] to fly; make haste; be on the wing, flutter

phérein [φέρω] to bear, carry

pnoiē [πνοιή, ῆς, ἡ] blowing, blast; wind, breath

potanós [ποτανός, ποτανά, ποτανόν] adj. winged, flying

ptēnós [πτηνός , πτηνή, πτηνόν] adj. flying, winged

pteróeis [πτερόεις, πτερόεσσα, πτερόεν] adj. feathered, winged

ptérōma [πτέρωμα, πτερώματος, τό] that which is feathered, plumage

pterōtós [πτερωτός , πτερωτή, πτερωτόν] adj. feathered, winged

pterón [πτερόν, πτεροῦ, τό] feather, wing; winged creature; anything like wings or feathers

Latin terms

Definitions based on Lewis & Short

āla, ālae (fem.) wing

penna, pennae (fem.) feather, plume, wing

plūma, plūmae (fem.) small soft feather, down

Bibliography

Aristophanes Birds:

Aristophanes Comoediae, ed. F.W. Hall and W.M. Geldart, vol. 2. F.W. Hall and W.M. Geldart. Oxford. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1907.

Online at Perseus

Sourcebook:

The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook: Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English. Gregory Nagy. 2013.

https://chs.harvard.edu/book/the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours-sourcebook/

Euipides Hippolytus:

English: translated by E. P. Coleridge. Revised by Mary Jane Rein. Further revised by Gregory Nagy

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek: Euripides, with an English translation by David Kovacs. Cambridge. Harvard University Press.

Online at Perseus

Ovid Metamorphoses:

English: translated by A. S. Kline.

Online at the Ovid Collection, University of Virginia

Latin: Ovid. Metamorphoses. Hugo Magnus. Gotha (Germany). Friedr. Andr. Perthes. 1892

Online at Perseus

Apollodorus Library:

English and Greek: Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921.

Online at Perseus

Iliad:

Sourcebook: Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek: Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

Hesiod Theogony:

English: Sourcebook Hesiodic Theogony 1–115 Translated by Gregory Nagy, 116–1022 Translated by J. Banks and adapted by Gregory Nagy

Online at the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek: Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Theogony. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914.

Online at Perseus

Apollodorus, Library Sir James George Frazer, Ed

English and Greek online at Perseus

Pindar Odes:

English: Odes. Pindar. Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

Online at Perseus

Greek: Pindar. The Odes of Pindar including the Principal Fragments with an Introduction and an English Translation by Sir John Sandys, Litt.D., FBA. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1937.

Online at Perseus

Plato Phaedrus:

English: Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by Harold N. Fowler. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925.

Online at Perseus

Greek: Platonis Opera, ed. John Burnet. Oxford University Press. 1903.

Online at Perseus

Aeschylus Eumenides:

English: Sourcebook Aeschylus Eumenides Translated by Herbert Weir Smyth, Revised by Cynthia Bannon, Further Revised by Gregory Nagy

Online in the Kosmos Society Text Library

Greek: Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. 2.Eumenides. Cambridge. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1926

Online at Perseus

Herodotus Histories:

English and Greek: Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

LSJ:

Liddell, Henry George, and Scott, Robert. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones, with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. 1940. Oxford. Clarendon Press.

Online at Perseus

Lewis and Short:

Charlton T. Lewis, Charles Short, A Latin Dictionary. Founded on Andrews’ edition of Freund’s Latin dictionary. revised, enlarged, and in great part rewritten by. Charlton T. Lewis, Ph.D. and. Charles Short, LL.D. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1879

Online at Perseus

Texts accessed March 2023.

Image credits

Attributed to The Gela Painter: Actors representing birds. Black-figured wine-jug, c 510–490BCE

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Domenico Piola: Daedalus and Icarus, 1670s

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Phrixos carried over the sea by a ram. Terracotta plaque, c 450 BCE.

Public domain, via Metropolitan Museum of Art

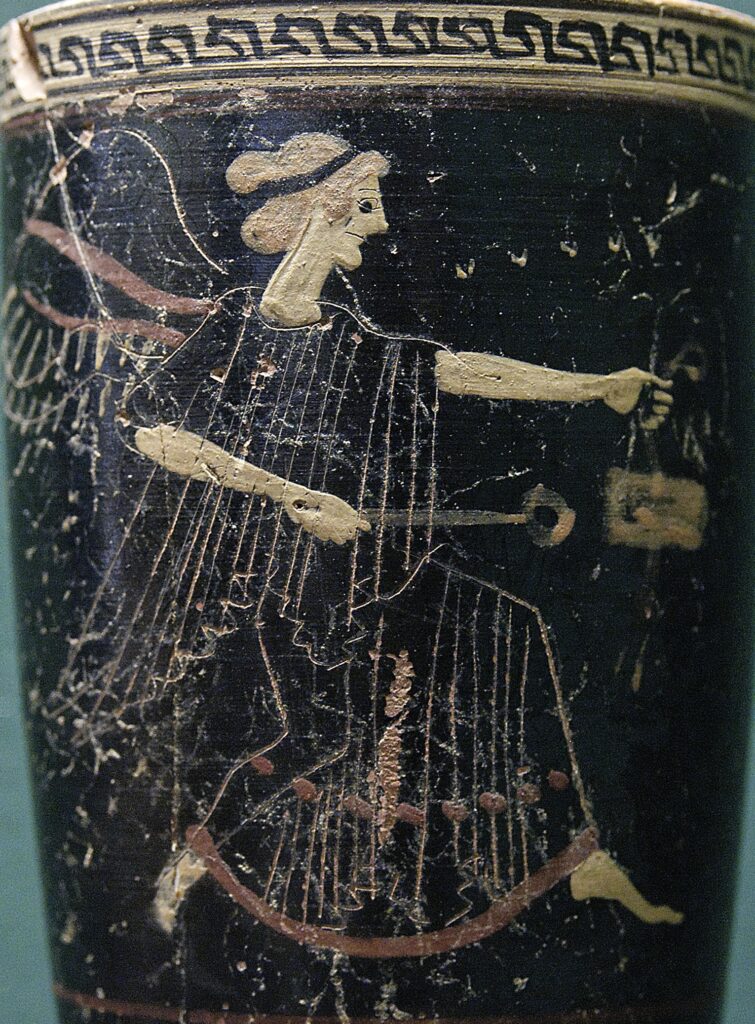

Diosphos Painter: Iris, Attic lekythos in Six’s technique (superposed colors). From Tanagra. c 500–490 BCE, Louvre

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Statue of Hermes tying his winged sandals as he raises his head and listens to Zeus’ command. Roman copy (2nd century) of a Greek bronze statue made by Lysippos around 330 BCE. Originally situated in the Villa Hadriana in Tivoli. Restored during the 18th century by Bartolomeo

Photo: Wolfgang Sauber. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

The sun (Helios) in his chariot drawn by four winged horses. Red-figured alyx-krater c 430 BCE.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Winged horse, late 6th century BCE. Louvre

Photo: Jastrow. Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license via Wikimedia Commons

Fresco of the 3rd style from Pompeii: Bellerophon, Pegasus and Athena, first half of 1st century

Photo: Sergey Sosnovskiy Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from: Hendrik Goltzius (after): Apollo Killing the Python 1589

Public domain from LACMA, via Wikimedia Commons

Scarab with sphinx, ankh, and winged snake. From Cyprus 1340–1100 BCE.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses, or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Images accessed March 2023.

___

Hélène Emeriaud, Janet M. Ozsolak, and Sarah Scott are members of Kosmos Society