This month’s Core Vocab word is phrēn, plural phrenes, [φρήν, φρένες] which is given the definition ‘physical localization of the thūmos‘.[1] As a reminder, the definition of thūmos is ‘heart, spirit’ (designates realm of consciousness, of rational and emotional functions); we have already looked at some passages relating to thūmos: you can find the post here. In modern English we refer to the mind as residing in the brain, and emotion is often referred to in connection with the heart and sometimes the gut; in ancient Greek both functions are referred to as residing in the phrēn or phrenes which equates to the midriff.

In this first passage, we see the terms phrēn and thūmos used interchangeably when the embassy goes to plead with Achilles:

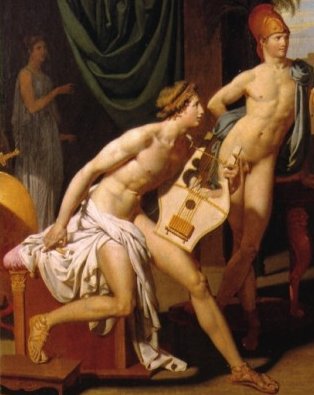

The two of them reached the shelters and the ships of the Myrmidons, 186 and they found Achilles diverting his heart [phrēn] as he was playing on a clear-sounding lyre [phorminx], 187 a beautiful one, of exquisite workmanship, and its cross-bar was of silver. 188 It was part of the spoils that he had taken when he destroyed the city of Eëtion, 189 and he was now diverting his heart [thūmos] with it as he was singing [aeidein] the glories of men [klea andrōn].

(Iliad 9.185–189, Sourcebook[2])

Phoenix concludes his speech:

As for you [= Achilles], don’t go on thinking [noeîn] in your mind [phrenes] the way you are thinking now. Don’t let a superhuman force [daimōn] do something to you 601 right here, turning you away, my near and dear one [philos].

Although he refers to thinking being located “in your mind [phrenes]”, he also seems to be making an appeal to Achilles’ emotion. Emotions also appear in Zeus’ mind, in the story told by Agamemnon:

…he was struck in his mind [phrēn] with a sharp sorrow [akhos]. 126 And right away he grabbed the goddess Atē by the head—that head covered with luxuriant curls— 127 since he was angry in his thinking [phrenes], and he swore a binding oath 128 that never will she come to Olympus and to the starry sky 129 never again will she come back, that goddess Atē, who makes everyone veer off-course [aâsthai].

(Iliad 19.125–129, Sourcebook)

We see a similar juxtaposition of atē with phrenes in this exchange between the Nurse and Phaedra:

(Nurse)…

236 These things are worth a lot of consultation with seers: 237 which one of the gods is steering you off course 238 and deflects your thinking [phrenes], child?

Phaedra

Wretched me, what have I done? 240 Where have I strayed from good sense? I have gone mad and fallen by derangement [atē] from a daimōn.(Euripides Hippolytus 236–242, Sourcebook)

Does this collocation occur elsewhere? (You can find guidance on using Perseus under PhiloLogic, including how to search for collocates, on the Learning page under ‘Going Beyond Reading a Translation‘, or follow this link to the Using Perseus Under PhiloLogic video demonstrations and Quick Guides.)

In the next example the word is used twice:

Chorus

510 In truth you have drawn out this plea of yours to your own content in showing honor [tīmē] to this unlamented tomb. As for the rest, since your phrēn is rightly set on action, put your fortune [daimōn] to the test and get to your work at once.

Orestes

It will be so. But it is not off the track to inquire 515 from what motive she came to send her libations, seeking too late to make amends [tīmē] for an irremediable experience [pathos]. They would be a sorry return [kharis] to send to the dead who have no phrenes: I cannot guess what they mean. The gifts are too paltry for her offense [hamartia].(Aeschylus Libation Bearers 510–519, Sourcebook)

In both places the word has not been translated from the Greek: we could perhaps infer that it is being used to refer to both mind and emotion when the Chorus uses the word. I found it interesting that in Orestes’ speech he says that the dead do not have phrenes: is he referring here to the physical location of the mind and emotion, or is he talking about how the dead do not have thoughts? We might consider the speech of Circe when she tells Odysseus to consult Teiresias:

[490] But first you [= Odysseus] must bring to fulfillment [teleîn] another journey and travel until you enter 491 the palace of Hādēs and of the dreaded Peresephone, 492 and there you all will consult [khrē-] the spirit [psūkhē] of Teiresias of Thebes, 493 the blind seer [mantis], whose thinking [phrenes] is grounded [empedoi]: 494 to him, even though he was dead, Persephone gave consciousness [noos], [495] so as to be the only one there who has the power to think [pepnusthai].

In Thebes, Oedipus consults Teiresias (who is still alive in this drama) about the plague that is afflicting the city, and again we see the word used:

Oedipus

300 Teiresias, whose soul grasps all things, that which may be told and that which is unspeakable, the secrets of heaven and the affairs of the earth—you feel with your phrēn, though you cannot see, what a huge plague haunts our polis. …

Teiresias

Alas, how terrible it is to have phrenes when it does not benefit those who have it.

(Sophocles Oedipus Tyrannus 300–304, 316, Sourcebook)

Finally here is an example of where the word is used simply to refer to that physical part of the anatomy:

Finally here is an example of where the word is used simply to refer to that physical part of the anatomy:

…..ὃ δ᾽ ὕστερος ὄρνυτο χαλκῷ

Πάτροκλος: τοῦ δ᾽ οὐχ ἅλιον βέλος ἔκφυγε χειρός, 480

ἀλλ᾽ ἔβαλ᾽ ἔνθ᾽ ἄρα τε φρένες ἔρχαται ἀμφ᾽ ἁδινὸν κῆρ.

ἤριπε δ᾽ ὡς ὅτε τις δρῦς ἤριπεν ἢ ἀχερωῒς

ἠὲ πίτυς βλωθρή, τήν τ᾽ οὔρεσι τέκτονες ἄνδρες

ἐξέταμον πελέκεσσι νεήκεσι νήϊον εἶναι:

ὣς ὃ πρόσθ᾽ ἵππων καὶ δίφρου κεῖτο τανυσθεὶς 485

βεβρυχὼς κόνιος δεδραγμένος αἱματοέσσης.[3]Patroklos then aimed in his turn, [480] and the spear sped not from his hand in vain, for he hit Sarpedon just where the midriff surrounds the ever-beating heart. He fell like some oak or silver poplar or tall pine to which woodmen have laid their axes upon the mountains to make timber for ship-building— [485] even so did he lie stretched at full length in front of his chariot and horses, moaning and clutching at the blood-stained dust.

(Iliad 16.479–486, Sourcebook)

Please join me here in the forum to find other passages where the word is used. Is it associated more with thinking or with emotion? Is it interchangeable with thūmos and/or do the words occur in close proximity? Are there more examples where it is used in a positive sense, and are there other places where it is associated with wrong thinking or derangement?

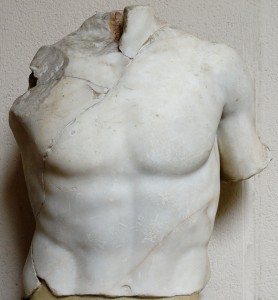

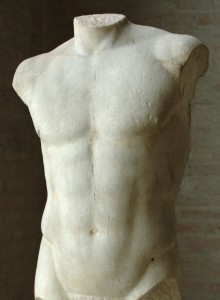

I have chosen to illustrate this post with scenes from the passages, and with torsos showing the midriff area. How would you choose to depict the word visually?

References

Updated 2018.05.19 to include citation references

[1] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. (H24H)

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

Image credits

Marie-Lan Nguyen (photo) Male nude torso, probably an athlete, Creative Commons CC BY 2.5

Jastrow (photo): Tarquinia Painter The embassy to Achilles, Wikimedia Commons

Detail from Ingres Achilles Receiving the Envoys of Agamemnon, Wikimedia Commons

Jastrow (photo): Dolon Painter Odysseus consulting the shade of Tiresias, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

Bibi Saint-Pol (photo) Torso of Apollo, public domain on Wikimedia Commons

___

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York where she specialized in philology, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Associate Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Hour 25, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.