The Core Vocab word this time is aretē [ἀρετή] which Professor Nagy translates as ‘striving for a noble goal, for high ideals; noble goal, high ideals’[1].

There are several passages in the Sourcebook[2] where we can find this word; for example, during the Embassy scene Phoenix says:

“Now, therefore, I say battle with your pride and beat it; cherish not your anger for ever; the might [aretē] and majesty [timē] of the gods are more than ours,

[500] but even the gods may be appeased; and if a man has sinned he prays the gods, and reconciles them to himself by his piteous cries and by incense, with drink-offerings and the savor of burnt sacrifice.”

(Iliad 9. 498–503, Sourcebook)…οὐδέ τί σε χρὴ

νηλεὲς ἦτορ ἔχειν: στρεπτοὶ δέ τε καὶ θεοὶ αὐτοί,

τῶν περ καὶ μείζων ἀρετὴ τιμή τε βίη τε.

καὶ μὲν τοὺς θυέεσσι καὶ εὐχωλῇς ἀγανῇσι

500 λοιβῇ τε κνίσῃ τε παρατρωπῶσ᾽ ἄνθρωποι

λισσόμενοι, ὅτε κέν τις ὑπερβήῃ καὶ ἁμάρτῃ.

(496–501, Perseus[3])

We know that Phoenix’s arguments are all ineffective, not just because Achilles does not want to be reconciled with Agamemnon, but because his illustrations all work against his arguments! Here he compares humans, and Achilles by implication, with the gods. How should we understand aretē here? Simply as ‘might’, or as having some noble or high ideals?

Hesiod has some words of wisdom, addressed to his inept brother Perses (see here for a discussion of nēpios), in which he also refers to aretē by contrasting humans with gods:

To be evil is an easy choice, and there are many ways to do it.

The way of evil is smooth and accessible.

But the immortal gods have put between them and us the sweat that goes with aretē.

290 The path towards it [aretē] is long and steep.

It is rough at first, but, as it reaches the top,

it finally becomes easy, hard as it was before.

(Works and Days 287–291, Sourcebook)τὴν μέν τοι κακότητα καὶ ἰλαδὸν ἔστιν ἑλέσθαι

ῥηιδίως: λείη μὲν ὁδός, μάλα δ᾽ ἐγγύθι ναίει:

τῆς δ᾽ ἀρετῆς ἱδρῶτα θεοὶ προπάροιθεν ἔθηκαν

290 ἀθάνατοι: μακρὸς δὲ καὶ ὄρθιος οἶμος ἐς αὐτὴν

καὶ τρηχὺς τὸ πρῶτον: ἐπὴν δ᾽ εἰς ἄκρον ἵκηται,

ῥηιδίη δὴ ἔπειτα πέλει, χαλεπή περ ἐοῦσα.

Here he seems to be contrasting aretē with ‘evil’ [kakotēta], and as something which has to be striven for, as a goal.

Plato’s Socrates has plenty to say about the concept, for example:

Never mind the manner, which may or may not be good; but think only of the justice [dikē] of my cause, and give heed to that: let the jury decide with their virtue [aretē] and the speaker speak truly [alēthēs]. …

… “Kallias,” I said, “if your two sons were foals or calves, there would be no difficulty in [20b] finding someone to put over them; we should hire a trainer of horses or a farmer probably who would improve and perfect [lit: make them more agathoi] them in their own proper virtue and excellence [aretē]; but as they are human beings, whom are you thinking of placing over them? Is there anyone who understands human and political virtue [aretē]? ….

I tell you that virtue [aretē] is not given by money, but that from virtue [aretē] come money and every other good [agathon] of man, public [= in the dēmos] as well as private. …

I say again that the greatest good of man is daily to converse about virtue [aretē], and all that concerning which you hear me examining myself and others, and that the life which is unexamined is not worth living”

(Plato Apology of Socrates 18a, 20b, 30b , 38a, Sourcebook)…τὸν μὲν τρόπον τῆς λέξεως ἐᾶν—ἴσως μὲν γὰρ χείρων, ἴσως δὲ βελτίων ἂν εἴη—αὐτὸ δὲ τοῦτο σκοπεῖν καὶ τούτῳ τὸν νοῦν προσέχειν, εἰ δίκαια λέγω ἢ μή: δικαστοῦ μὲν γὰρ αὕτη ἀρετή, ῥήτορος δὲ τἀληθῆ λέγειν. (from 18a)

‘ὦ Καλλία,’ ἦν δ᾽ ἐγώ, ‘εἰ μέν σου τὼ ὑεῖ πώλω ἢ μόσχω ἐγενέσθην, εἴχομεν ἂν αὐτοῖν ἐπιστάτην λαβεῖν καὶ μισθώσασθαι ὃς ’ ‘ [20β] ἔμελλεν αὐτὼ καλώ τε κἀγαθὼ ποιήσειν τὴν προσήκουσαν ἀρετήν, ἦν δ᾽ ἂν οὗτος ἢ τῶν ἱππικῶν τις ἢ τῶν γεωργικῶν: νῦν δ᾽ ἐπειδὴ ἀνθρώπω ἐστόν, τίνα αὐτοῖν ἐν νῷ ἔχεις ἐπιστάτην λαβεῖν; τίς τῆς τοιαύτης ἀρετῆς, τῆς ἀνθρωπίνης τε καὶ πολιτικῆς, ἐπιστήμων ἐστίν; (from 20a–20b)

λέγων ὅτι ‘οὐκ ἐκ χρημάτων ἀρετὴ γίγνεται, ἀλλ᾽ ἐξ ἀρετῆς χρήματα καὶ τὰ ἄλλα ἀγαθὰ τοῖς ἀνθρώποις ἅπαντα καὶ ἰδίᾳ καὶ δημοσίᾳ.’ (from 30b)

ἐάντ᾽ αὖ λέγω ὅτι καὶ τυγχάνει μέγιστον ἀγαθὸν ὂν ἀνθρώπῳ τοῦτο, ἑκάστης ἡμέρας περὶ ἀρετῆς τοὺς λόγους ποιεῖσθαι καὶ τῶν ἄλλων περὶ ὧν ὑμεῖς ἐμοῦ ἀκούετε διαλεγομένου καὶ ἐμαυτὸν καὶ ἄλλους ἐξετάζοντος, ὁ δὲ ἀνεξέταστος βίος οὐ βιωτὸς ἀνθρώπῳ (from 38a)

Again there is that sense of aspiration, but the concept seems to be more an ideal than with the more aspirational, striving, references of the other two examples.

How these and other passages help us to understand the range of meanings of this word? To what extent is there a shift in emphasis between the Homeric epic and the age of philosophy?

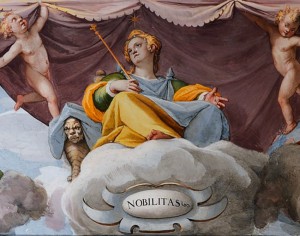

I have chosen a fresco painting depicting ‘Nobility’, and a sculpture embodying aretē. In both cases, perhaps because this is a feminine noun, or perhaps because it is an abstract quality, it is personified as a female figure. And yet the word originally seems to refer more to male qualities of courage and might.

What other passages can you find, either in the Sourcebook or by searching on Perseus? How would you choose to illustrate or embody this word? Join me in the forum discussion!

Sarah Scott is an editor and technical author living in Scotland. She has taken part in all four iterations of HeroesX, being one of the Community TAs in v2–v3 and Associate Producer in v4, and has a lifelong love of language, literature, and learning.

Image credits

Livioandronico2013, Fresco room Nobility in Villa d’Este (Tivoli), Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license

Carlos Delgado: Arete sculpture in Ephesus, in modern-day Turkey, CC-BY-SA

References

Updated 2019.05.02 to include reference citations

[1] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. (H24H)

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.