This next exploration of Core Vocabulary—taken from terms in H24H[1] and the associated Sourcebook[2] —features ponos [πόνος], glossed as ‘ordeal, labor, pain’.

In Homeric Greek, Autenrieth[3] explains further: “labor, toil, esp. of the toil of battle,…frequently implying suffering, grievousness, ‘a grievous thing,’…hence joined with ὀιζύς [oizus “woe, misery”], κήδεα [kēdea “cares, troubles,, sorrows” ], ἀνιη [aniē/aniā, “grief, sorrow, distress, trouble; bane”]”

In this first example, we pick up where Achilles has been raging on the battlefield, and the Trojans are trying to escape his onslaught. Apollo has hidden his latest target, Agenor, in a cloud of mist. Then Apollo himself has taken on the form of Agenor, and has been running toward the Scamander river, giving the Trojans the opportunity to escape to the security of the city. Now, he turns and taunts Achilles:

αὐτὰρ Πηλείωνα προσηύδα Φοῖβος Ἀπόλλων:

‘τίπτέ με Πηλέος υἱὲ ποσὶν ταχέεσσι διώκεις

αὐτὸς θνητὸς ἐὼν θεὸν ἄμβροτον; οὐδέ νύ πώ με

10 ἔγνως ὡς θεός εἰμι, σὺ δ᾽ ἀσπερχὲς μενεαίνεις.

ἦ νύ τοι οὔ τι μέλει Τρώων πόνος, οὓς ἐφόβησας,

οἳ δή τοι εἰς ἄστυ ἄλεν, σὺ δὲ δεῦρο λιάσθης.

οὐ μέν με κτενέεις, ἐπεὶ οὔ τοι μόρσιμός εἰμι.[4]But Phoebus Apollo addressed the son of Peleus: “Why ever, son of Peleus, are you with quick feet pursuing me although you are a mortal-liable-to-death, me, a non-mortal god? And now you have not yet recognized that am I a god; but you are raging [= verb from menos] unceasingly. Really now, do you not at all have a concern for your toil [ponos] over the Trojans, whom you put to flight, who, let me tell you, are cooped up in the town, while you have been drawn here. You will not kill me, since, let me tell you, I am not fated-to-die.”

Iliad 22.7–13

Although Apollo refers to the ponos of Achilles’ rampage against the Trojans, the pursuit of Apollo—who was in the guise of a Trojan—has also been a battle-toil for Achilles, and a fruitless one as it turns out: he has been lured away from the real Trojans who have had time to escape.

As we might expect the word is more frequent in the Iliad than the Odyssey, but it occurs there too. Here is just one example. Odysseus, back on the beach at Ithaka, has met Athena disguised as a shepherd, and told lying story. Athena then changes into the appearance of a tall, skilled woman:

… οὐδὲ σύ γ᾽ ἔγνως

300 Παλλάδ᾽ Ἀθηναίην, κούρην Διός, ἥ τέ τοι αἰεὶ

ἐν πάντεσσι πόνοισι παρίσταμαι ἠδὲ φυλάσσω,

καὶ δέ σε Φαιήκεσσι φίλον πάντεσσιν ἔθηκα,

νῦν αὖ δεῦρ᾽ ἱκόμην, ἵνα τοι σὺν μῆτιν ὑφήνω

χρήματά τε κρύψω, ὅσα τοι Φαίηκες ἀγαυοὶ

305ὤπασαν οἴκαδ᾽ ἰόντι ἐμῇ βουλῇ τε νόῳ τε,

εἴπω θ᾽ ὅσσα τοι αἶσα δόμοις ἔνι ποιητοῖσι

κήδε᾽ ἀνασχέσθαι: σὺ δὲ τετλάμεναι καὶ ἀνάγκῃ,

μηδέ τῳ ἐκφάσθαι μήτ᾽ ἀνδρῶν μήτε γυναικῶν,

πάντων, οὕνεκ᾽ ἄρ᾽ ἦλθες ἀλώμενος, ἀλλὰ σιωπῇ

310 πάσχειν ἄλγεα πολλά, βίας ὑποδέγμενος ἀνδρῶν.…and you did not recognize Pallas Athena, daughter of Zeus, who always

in all your trials [ponoi] stand beside and guard you, and caused you to be near-and-dear [philos] to all the Phaeacians, now again I have come here, in order that I may weave a device [mētis] with you and conceal your possessions, as many as the illustrious Phaeacians bestowed on you when you came homeward by means of my plan [boulē] and intention [noos], and tell you about your alloted destiny [aisa] in your (well)-made house the sorrows [kēdea] you are to endure: but you will also be compelled to submit and not to speak out about it either to men or to women, all of them, that you have come back from your wandering, but in silence experience [paskhein] many pains [algea], when you endure violent-force [biē] from men.Odyssey 13.299–310

As with the first passage, the hero does not initially recognize the god who has appeared before him in disguise.

Even when his ordeal of fighting the suitors is over and Odysseus and Penelope have been reunited, he tells her that there is more to come:

At last, however, Odysseus of many-devices said, “Wife, we have not yet reached the end of our trials [āthloi]. I have an unknown amount of toil [ponos] still to undergo. [250] It is long and difficult, but it is necessary for me to fulfil it [bring it to telos], for thus the spirit [psūkhē] of Teiresias prophesied concerning me, on the day when I went down into Hādēs to ask about my return [nostos] and that of my companions.

Odyssey 23.247–253, adapted from Sourcebook

He goes on to explain how he will have to travel inland to plant his oar for Poseidon in an area where it is taken for a winnowing-shovel.

Back once more to the Iliad, and we find the word not only used for individual toil, but also used in a general or collective battle context, as in these examples:

The bossed shields beat one upon another, and there was a tramp as of a great multitude— [450] death-cry and shout of triumph of slain and slayers, and the earth ran red with blood. As torrents swollen with rain course madly down their deep channels till the angry floods meet in some gorge, [455] and the shepherd on the hillside hears their roaring from afar—even such was the toil [ponos] and uproar of the armies as they joined in battle.

Iliad 4.448–456, Sourcebook

|599 He [Nestor] was seen and noted by swift-footed radiant Achilles, |600 who was standing on the spacious stern of his ship, |601 watching the sheer pain [ponos] and tearful struggle of the fight.

Iliad 11.599–601, Translation by Gregory Nagy, H24H Hour 6, Text F

The term does not only occur in connection with fighting, though. It can refer to the careful work involved in the correct preparation of a sacrifice and feast, which includes , as in this example:

αὐτὰρ ἐπεί ῥ᾽ εὔξαντο καὶ οὐλοχύτας προβάλοντο,

αὐέρυσαν μὲν πρῶτα καὶ ἔσφαξαν καὶ ἔδειραν,

460 μηρούς τ᾽ ἐξέταμον κατά τε κνίσῃ ἐκάλυψαν

δίπτυχα ποιήσαντες, ἐπ᾽ αὐτῶν δ᾽ ὠμοθέτησαν:

καῖε δ᾽ ἐπὶ σχίζῃς ὁ γέρων, ἐπὶ δ᾽ αἴθοπα οἶνον

λεῖβε: νέοι δὲ παρ᾽ αὐτὸν ἔχον πεμπώβολα χερσίν.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ κατὰ μῆρε κάη καὶ σπλάγχνα πάσαντο,

465 μίστυλλόν τ᾽ ἄρα τἆλλα καὶ ἀμφ᾽ ὀβελοῖσιν ἔπειραν,

ὤπτησάν τε περιφραδέως, ἐρύσαντό τε πάντα.

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ παύσαντο πόνου τετύκοντό τε δαῖτα

δαίνυντ᾽, οὐδέ τι θυμὸς ἐδεύετο δαιτὸς ἐΐσης.But when they had prayed and sprinkled the barley-meal, they first drew back the heads of the victims and cut their throats and flayed them. [460] They cut out the thigh-bones, wrapped them round in two layers of fat, set some pieces of raw meat on the top of them. 462 And the old man burned them [= the thigh bones] over splinters of wood, and bright wine did he 463 pour over them, while the young men were getting ready for him the five-pronged forks that they were holding in their hands. When the thigh-pieces were burned and they had tasted the innards, [465] they cut the rest up small, put the pieces upon the spits, roasted them till they were done, and drew them off: but when they finished their toil [ponos] and had made ready the feast they distributed the portions, and their spirits [thūmos] did not lack anything in the equally-shared feast.

Iliad 1.458–468, adapted from Sourcebook

Moving to tragedy, we find the word used of various ordeals, as in this example when Apollo gives Orestes advice about escaping the fury of the vengeful Furies:

….try to get away and do not lose heart. 75 For they will drive you on even as you go across the wide land, always in places where wanderers walk, beyond the sea [pontos] and the island cities. Do not grow weary brooding on your ordeal [ponos], but when you have come to the polis of Pallas, 80 sit yourself down and clasp in your arms the ancient wooden image of the goddess. And there we shall find judges for your case and have spellbinding and effective mūthoi to release you from your labors [ponoi] completely. For I persuaded you to kill your mother.

Aeschylus Eumenides 74–84, Sourcebook

In several of the examples we have gods speaking to mortals about the ponos that they have to undergo. But mortals can also speak about this matter, as when the Nurse is concerned about the erratic behavior of Phaedra who is longing to be close to Hippolytus:

In several of the examples we have gods speaking to mortals about the ponos that they have to undergo. But mortals can also speak about this matter, as when the Nurse is concerned about the erratic behavior of Phaedra who is longing to be close to Hippolytus:

185 It is better to be ill than to care for the ill, for one is a single trouble, but to the other is attached both heartsickness and labor [ponos] with one’s hands. The whole of human life is full of pain, 190 and there is no rest from trouble [ponoi]. But if there is anything more philon than life, darkness hides it in the clouds in its embrace, and we show ourselves to be wretchedly in love with that thing which glistens on the earth, 195 because of inexperience of any other life, and the things which lie below the earth are unrevealed. On tales [mūthoi] we vainly drift.

Euripides Hippolytus 185–196, Sourcebook

My initial impression is that the word is used sometimes in a general way, to mean the sheer hard work of struggling through ordeals such as the difficulties of homecoming for Odysseus, of being pursued by the Furies for Orestes, and perhaps more often the toil of battle for both Achaeans and Trojans. What other types of toil does ponos refer to?

The word is used for the experience of individuals and collectively. Are there differences in the situations where it is used for an individual in contrast to a collective group of people?

It also seems to have a more ritualized context, as with the preparation of a sacrifice and feast. Are there other specific circumstances where the term is used?

I hope other members of the community will join the discussion in the Forum to share other passages where ponos occurs.

References

[1] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. (H24H)

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[3] Autenrieth, Georg. 1891. A Homeric Dictionary for Schools and Colleges. New York. Harper and Brothers. Available on Perseus.

[4] Greek texts:

Iliad: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Online at Perseus

Odyssey: Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online at Perseus

(Updated March 2021 to add Reference [4] with links to Greek texts on Perseus)

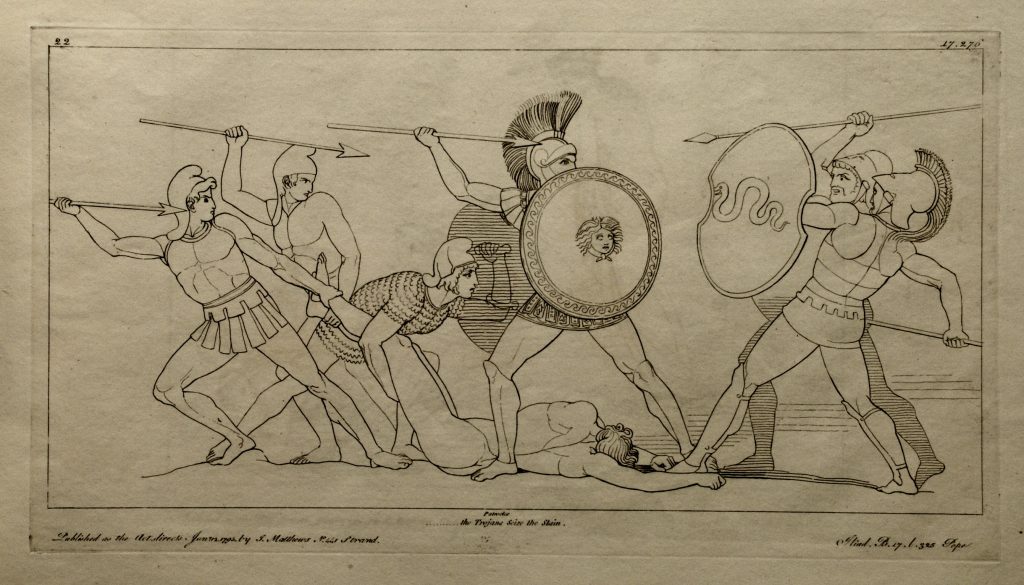

Image credits

Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman ‘The Trojans Seize the Slain’ Photographed/scanned by H.-P.Haack (Antiquariat Dr. Haack Leipzig) [CC BY 3.0 or Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Intaglio of Apollo and Achilles before the Walls of Troy, Roman, 31BCE–14CE, Creative Commons CC0, The Walters Art Museum 42.1059.

Marie-Lan Nguyen (photo) Athena Parthenos, by Antiochos (1st century CE), copy of Phidias (5th century BCE) with 17th-century restorations, Altemps palace, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ambrosian Iliad pictures 20 and 21 depicting battle scenes, 5th centruy CE, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Jastrow (photo) Sacrifice scene, by Kraipale Painter, detail from Attic red-figure oinochoe c 430–425BCE, Louvre G 402, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Detail from Marie-Lan Nguyen (photo) Phaedra with an attendant, fresco from Pompeii c60–20 BCE, British Museum 1856.6-25.5, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

______

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York where she specialized in philology, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Executive Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.