A guest post by Sarah Scott

The Core Vocab word for this month, taken from those terms listed in Gregory Nagy’s The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours[1] and related Sourcebook[2], is oikos [οἶκος] ‘house, dwelling, abode; resting place of cult hero; family line’; verb oikeîn [οἰκεῖν] ‘have a dwelling’

Sometimes it simply means a house or home, as in this speech of Agamemnon during his argument with Khrysēs about the priest’s daughter:

I have set my heart on keeping her in my own house [= oikos], for I prefer her to my own wife Clytemnestra, whom I courted when young, whose peer she is in [115] both form and feature, in intelligence and accomplishments.

(Iliad 1.113–115, Sourcebook)

Telemachus also uses the word when he explains to his guest—Athena in the guise of Mentes—what the suitors are doing:

“Sir,” said the spirited Telemachus, “as regards your question, so long as my father was here it was well with us and with the house [= oikos], but the gods in their displeasure have willed it otherwise, [235] and have hidden him away more closely than mortal man was ever yet hidden. I could have borne it better even though he were dead, if he had fallen with his men in the district [dēmos] of Troy, or had died with friends around him when the days of his fighting were done; for then the Achaeans would have built a mound over his ashes, [240] and I should myself have been heir to his renown [kleos]; but now the storm-winds have spirited him away we know not wither; he is gone without leaving so much as a trace behind him, and I inherit nothing but dismay. Nor does the matter end simply with grief for the loss of my father; the gods have laid sorrows upon me of yet another kind; [245] for the chiefs from all our islands, Doulikhion, Samē, and the woodland island of Zakynthos, as also all the principal men of Ithaca itself, are eating up my house [= oikos] under the pretext of paying their court to my mother, who will neither point blank say that she will not marry, nor yet [250] bring matters to an end; so they are making havoc of my estate, and before long will do so also with myself.”

(Odyssey 1.230–251, Sourcebook)

Perhaps the sense of a personal home and of a lineage come into play in this speech of Electra:

But now, an exile from home and fatherland, you have perished miserably, far from your sister.

νῦν δ᾽ ἐκτὸς οἴκων κἀπὶ γῆς ἄλλης φυγὰς

κακῶς ἀπώλου, σῆς κασιγνήτης δίχα,

(Sophocles Electra, 1136–1137, translated by Sir Richard Jebb, Perseus)

and again in this speech, oikos in the plural is used to refer to families:

I say simply that when one knows how to say and do what is gratifying to the gods, in praying and sacrificing, that is holiness, and such things bring salvation to individual families and to states.

τόδε μέντοι σοι ἁπλῶς λέγω, ὅτι ἐὰν μὲν κεχαρισμένα τις ἐπίστηται τοῖς θεοῖς λέγειν τε καὶ πράττειν εὐχόμενός τε καὶ θύων, ταῦτ᾽ ἔστι τὰ ὅσια, καὶ σῴζει τὰ τοιαῦτα τούς τε ἰδίους οἴκους καὶ τὰ κοινὰ τῶν πόλεων:

(Plato Euthyphro 14b, translated by Harold North Fowler, Perseus)

In The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, Gregory Nagy gave this as an example of a word that can have an additional sacred meaning, introducing it in the discussion of the mystical language used to refer to cult heroes, for example as employed in the narratives of Herodotus and Philostratus:

Among these indirect references are special words that have a general meaning in non-sacral contexts but a specific meaning in the sacred contexts of hero cult. One of these words is oikos, which means ‘house’ in everyday contexts but refers to the sacred space or ‘dwelling’ that houses the corpse of the hero in the sacred contexts of hero cult. A striking example of this sacral meaning of oikos, as we will see in Hour 18, is a passage in Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus (627).

(15§26)

A further explanation is provided in 15§37:

oikos and oikēma and oikodomēma, meaning ‘house’ and ‘dwelling’ and ‘constructed dwelling’: These words refer to any built structures within the natural setting of the sacred space of the cult hero; we have seen such wording already in the narrative of Herodotus (9.116.1–3), quoted in Text E, about the dwelling place of the cult hero Protesilaos.

In this next passage, Orestes has been acquitted by the casting vote of Athena, and he initially seems to be talking about his ancestral home:

Pallas, you have saved [sōzein] my house! 755 You have restored me to my home [oikos] when I was deprived of my fatherland. The Hellenes will say, “A man of Argos has an abode [oikeîn] again on the property of his ancestors, by the grace of Pallas and of Loxias and of that third god, the one who brings everything to fulfillment, 760 the sōtēr”—the one who respected my ancestral destiny, and saved [sōzein] me, when he saw who was defending my mother’s interests.

(Aeschylus Eumenides 755–761, Sourcebook)

I will return to my home now, after I swear an oath to this land and to your people for the future and for all time to come, 765 that no captain of my land will ever come here and bring a well-equipped spear against them. For when we ourselves are in our graves, if anyone transgresses our oaths, we will enforce them by inflicting extraordinary failures on the transgressors, 770 by giving them heartless marches and ill-omened ocean voyages, so that pain [ponos] will make them feel regret. But while the men of the future stay on the straight course, they will always give tīmē to the city of Pallas with their allied spear, and we will remain more well disposed to them.

(Aeschylus Eumenides 762–774, Sourcebook)

Here he seems to be envisaging a future after his own death. Is he foretelling a time when he would have the same influence as a cult hero to affect the success or failure of the people in his own land?

Returning to the Odyssey, although the following passage initially appears to refer to a simple dwelling-place, it is also a place of transformation for Laertes:

Then the old Sicilian woman took Laertes into the house [oikos] and washed him and anointed him with oil. She put him on a good cloak, and Athena came up to him and gave him a more imposing presence, making him taller and stouter than before. [370] When he came back from the bath [asaminthos] his son was surprised to see him looking so like [enalinkios] immortal gods [athanatoi theoi], and said to him, “My dear father, some one of the gods has been making you much taller and better-looking.”

(Odyssey 24.365–374, adapted from Sourcebook)

He is described as looking just like the immortal gods after emerging from the house. A recent article in Classical Inquiries discusses similar bathing scenes, and direct contact with Athena, and the phrase athanatoisi theois enalinkion. Gregory Nagy provides examples involving Telemachus and Odysseus, and explains this transformation as follows:

{§9} …. And, in terms of the ritual transformation of Odysseus by way of a sacred bath in an asaminthos or by way of a sacred contact with the wand of the goddess Athena herself, this mortal not only looks just like one of the gods but he actually becomes a god in the ritual moment marked by the similes that liken him to the god.

§10. I offer at this point this general formulation: for a mortal to appear like an immortal to other mortals is to become a divinity in a ritual moment of epiphany—as marked by the similes that make mortals equal to divinities in that ritual moment.[3]

So I am now wondering whether, as the location for such a ritual bath and/or contact with a god, the house, oikos, becomes similarly transformed into a sacred dwelling, in this case even before the death of Laertes.

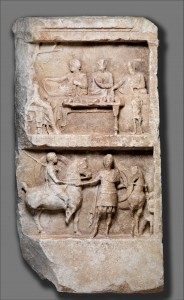

The images I have chosen include examples from grave monuments and tombs, which provide a selection of illustrations of imagery and locations associated with cult hero worship.

I hope you will join me in the forum to discover and discuss further examples of the word, and which layer of meaning comes into play.

References

[1] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. Translations of source texts prepared with Core Vocabulary words tracked.

[2] Nagy, Gregory. “A Bathtub in Pylos.” Classical Inquiries. 2017.03.16, accessed March 17th, 2017

Image credits

Miguel Hermoso Cuesta (photo): Paestum, heroon. Shrine to a local hero, Paestum (originally the Greek colony of Poseidonia), Southern Italy. Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

Marble grave relief with a funerary banquet and departing warriors. Hellenistic, 2nd century BCE. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain.

Return of a mounted warrior: wall painting from chamber tomb, mid-4th century BCE, Greek, from Southern Italy. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Public domain.

Ingo Mehling (photo): Sagalassos – Heroon. Shrine of a cult hero, Roman, Augustan period, Sagalassos, Turkey. Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0.

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

___

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York where she specialized in philology, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Associate Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.