This time the Core Vocab word, taken from terms in H24H[1] and the associated Sourcebook,[2] is ekhthros [ἐχθρός], glossed by Gregory Nagy as ‘enemy [within the community], non-philos.’ The plural form is ekhthroi; and the associated noun is ekhthra or ekhthos ‘hatred, enmity’.

There is a difference between an ekhthros who is a personal enemy, and a polemos or polemoi in the plural, a collective enemy, an opposing force in war.

It seemed appropriate to look at this word initially in the context of this month’s Book Club selection, Sophocles Ajax, in which it appears several times and might be considered one of the key words for this drama.

In this exchange between Athena and Odysseus it is clear that he and Ajax have personal enmity:

Athena

What is the danger? Was he not a man before?Odysseus

Yes, a man hostile [ekhthros] to me in the past, and especially now.Athena

And is not the sweetest mockery the mockery of enemies [ekthroi]?Sophocles Ajax 77–79, adapted from translation by Sir Richard Jebb

Ajax himself makes it clear that he considers Odysseus hateful:

O Zeus, forefather of my forebears, if only I might destroy that deep dissembler, that hateful [ekhthros] sneak, and [390] the two brother-kings, and finally die myself, also!

Sophocles Ajax 388–391 , adapted from translation by Sir Richard Jebb

Odysseus does, however, respect Ajax, as we see in this exchange with Agamemnon, in which the opposite concept, being philos, ‘near-and-dear’, also features:

Agamemnon

[1350] Reverence, I tell you, is not easily practiced by the autocrat [turannos].Odysseus

But it is easy to grant dispensations [tīmai] to friends [philos, plural] when they advise well.Agamemnon

A good [esthlos] man should listen to those in charge.Odysseus

Stop! Your power is victorious when you surrender to your friends [philos, plural].Agamemnon

Remember to what sort of man you show this kindness [kharis]!Odysseus

[1355] The man was once my enemy [ekthros], yes, but he was also noble.Agamemnon

Why do you do this? Why do you so respect an enemy’s [ekhtros] corpse?Odysseus

I yield to his excellence [aretē] much more than his hostility [ekhthra].Agamemnon

Men who act as you do are the unstable sort in humankind.Odysseus

Quite the majority of men, I assure you, are friendly [philoi] at one time, and bitter at another.Agamemnon

[1360] So then, are these the type of friends [philoi] that you recommend we make?Sophocles Ajax 1350–1360, adapted from translation by Sir Richard Jebb

The immediate cause of Ajax’s hostility to Odysseus is the dispute over the armor of Achilles. But is there evidence from the play or from other texts that there were other causes for enmity, or they were formerly friends?

Not surprisingly, Medea, who is angry and upset at her husband Jason’s forthcoming marriage to the king’s daughter, uses the word, as in this speech:

Not surprisingly, Medea, who is angry and upset at her husband Jason’s forthcoming marriage to the king’s daughter, uses the word, as in this speech:

There are ordeals [agōnes] still in store for the couple newly-wed, and no small labors [ponoi] for their relations. Do you think that I would ever have fawned on that man, unless to gain some profit or to form some scheme? |370 No, I would not even have spoken to him or touched him with my hand. But he has progressed so far in folly that, though he might have checked my plot by removing me from the land, he has allowed me to stay this day, in which I will lay low in death three of my enemies [ekhthroi]: |375 a father, his daughter, and my husband too.

Euripides Medea 366–375[4]

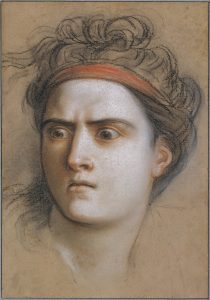

Clytemnestra has long held great antagonism toward Agamemnon because he killed their daughter. As with Medea, her enmity also extends to his new concubine Kassandra, as we can see when she justifies killing them:

Clytemnestra has long held great antagonism toward Agamemnon because he killed their daughter. As with Medea, her enmity also extends to his new concubine Kassandra, as we can see when she justifies killing them:

Much have I said before to serve my need and I shall feel no shame to contradict it now. For how else could one, devising hate [ekhthra] against enemies [ekhthroi] 1375 who bear the semblance of philoi, fence the snares of ruin too high to be overleaped? This is the agōn of an ancient feud, pondered by me of old, and it has come—however long delayed. I stand where I dealt the blow; my purpose is achieved.

Aeschylus Agamemnon 1372–1379, Sourcebook

Again, as with Medea, she uses the term agōn. Is this a collocation that appears elsewhere? Are there other terms that often appear in close proximity to ekhthros?

Theognis of Megara prays for vengeance on his enemies:

May Zeus grant me repayment of the philoi who love me,

338 and that I may have more power than my personal enemies [ekhthroi].

Thus would I have the reputation of a god among men,

340 if my destined death overtakes me when I have exacted repayment.

O Zeus, Olympian, bring my timely prayer to its ultimate fulfillment!

342 Grant that I have something good happen in place of misfortunes.

But may I die if I find no respite from cares brought on by misfortunes.Theognis of Megara 338–343, Sourcebook

Does vengeance always accompany the recognition of such enmity?

Perhaps not. Here, for example, is Achilles—also referring to Agamemnon—in his reply to Odysseus in the Embassy scene:

Hateful [ekhthros] is that man to me, as hateful as the gates of Hādēs, 313 the man who hides one thing in his thinking and says another thing.

Iliad 9.312–313, Sourcebook

He rejects the offer, and threatens to leave. But he has already withdrawn from the fighting. So is he threatening this as revenge? His personal enmity with Agamemnon did not go as far as killing him, partly as a result of Athena’s intervention in Iliad 1.194–200. What other examples are there where being ekhthroi does not actually lead to killing?

When Sappho invokes the Nereids and prays for her brother’s wellbeing, she says:

1 O Queen Nereids, unharmed [ablabēs] 2 may my brother, please grant it, arrive to me here [tuide], 3 and whatever thing he wants in his heart [thūmos] to happen, 4 let that thing be fulfilled [telesthēn]. [5] And however many mistakes he made in the past, undo them all. 6 Let him become a joy [kharā] to those who are near-and-dear [philoi] to him, 7 and let him be a pain [oniā] to those who are enemies [ekhthroi]. As for us, 8 may we have no enemies, not a single one.

Sappho Song 5.1–9, Sourcebook

Does this mean that in the song culture people were either philoi or ekhthroi, or were there people who were neither one nor the other? What evidence can you find to help answer this question?

The passages above are just a few examples of where the word is used. In these and other texts, what do people say about those they regard as ekhthroi? Do any particular individuals appear in this context more often than others?

Please join me in the forum to continue the dialogue about this term!

References

[1] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013. (H24H)

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[3] Sophocles. The Ajax of Sophocles. Edited with introduction and notes by Sir Richard Jebb. Sir Richard Jebb. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. 1893. On Perseus.

[4] Euripides Medea, translation by E.P. Coleridge, revised by Roger Ceragioli, further revised by Gregory Nagy. Newly revised by members of Kosmos Society. Available at Kosmos Society Text Library.

Image credits

Jastrow (photo) Taleides Painter: Dispute between Ajax and Odysseus for Achilles’ armor. Attic black-figure oinochoe, circa 520BCE. Kalos inscription. Louvre Museum. Public domain.

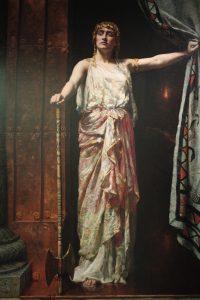

Charles Antoine Coypel Medea circa 1715. Donated to Wikimedia Commons as part of a project by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Stephencdickson (photo) John Collier Clytemnestra 1882, Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Bibi Saint-Pol (photo) Kleophiades Painter The embassy to Achilles: Phoenix and Odysseus in front of Achilles. Attic red-figure hydria. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung A symposiast sings the beginning of a Theognidian verse. Kylix from Tanagra Boeotia 5th century BCE. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website. Images and texts accessed May 2018.

______

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York where she specialized in philology, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Executive Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.