Everything about siege machines is difficult and hard to understand, either because of the intricacy and inscrutability of their depiction, or because of the difficulty of comprehending the concepts, or, to say it better, because of their incomprehensibility to most men…

The most competent military commander, kept safe by Providence above because of his piety, and obedient to the command and judgment and good counsel of our most divine emperors, when he is about to besiege the enemy and rebels, must first, by going about <himself>, precisely observe the position of the cities; and having provided for the secure protection of his own host above all, begin the siege, first appearing to attack the fortifications in certain locations, in order that the enemy be tricked into making their preparations there, and then deploying machines against other places. He should continuously attack the weaker parts of the walls with relays of tagmata of soldiers, with loud noise distract those inside and sound trumpets by night at the stronger parts, in order that the majority, assuming that these parts are captured, might flee from the curtain walls with the others.

from the Instructions for Siege Warfare by the Anonymous Byzantinus, translated by Denis F. Sullivan

This month’s Book Club selection is Siegecraft, a treatise written in 10th century Byzantium by an unknown author traditionally referred to as Heron of Byzantium. The manuscript is part of a collection in the Vatican where it is designated Vaticanus graecus 1605.[1] Since the parts of this manuscript which are usually written in colored ink were never added, the name of the author and the initial letter of each paragraph are missing. The only reference to Heron’s authorship is from a scholiast’s note of “Ἡρων” which was made several centuries later at the start of the text. Since some of the examples in the text show a familiarity with Constantinople, and because Heron of Alexandria was already known as an inventor of mechanical contrivances, the unattested authorship of Heron of Byzantium took root.[2]

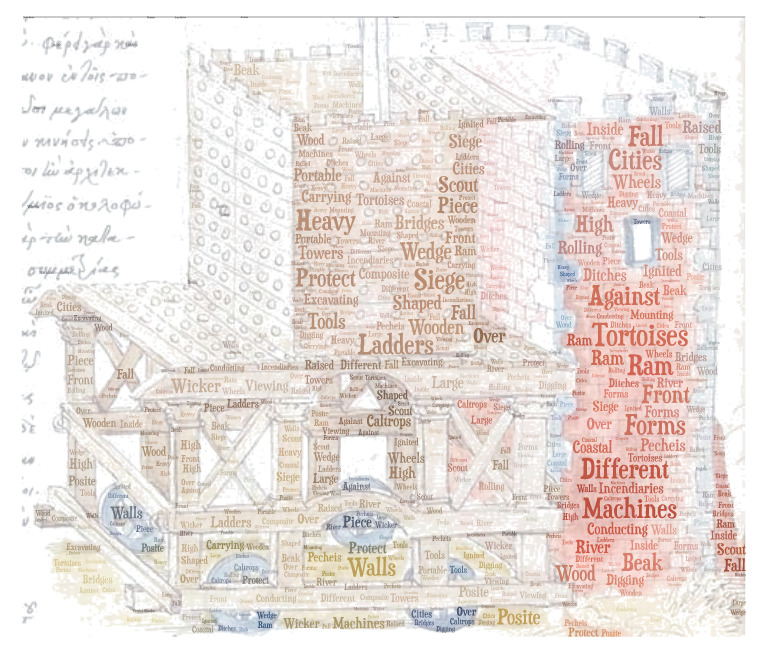

The work follows the tradition of didactic manuals going back to the 4th century BCE dealing with the engineering aspect of warcraft. Known in Greek as a πολιορκητίκα [poliorkētika], they expound on techniques for bringing armies close to enemy fortifications and then to breach them.[3] The author intended his work to aid the Byzantine offensive against Arab cities. It draws heavily on earlier works on siegecraft by late Hellenistic authors, for example, Apollodorus of Damascus and Heron of Alexandria. The author explains that his intention in writing the handbook is to make the material accessible to his readers. To achieve this, he has enhanced his text with realistic examples and also with many drawings[4].

Please read any translation you like. The dual language version below is available online for free:

Denis F. Sullivan (2000)—Online at University of Maryland

For our regular discussion, we will meet via Zoom on Tuesday, May 28 at 11 a.m. EDT.

As always, our discussion will start and continue in the Forum where the Zoom link will be posted on the date above.

Happy reading!

Notes

1 Vaticanus graecus 1605, Digitized Images of Greek Manuscripts, Princeton University Library

2 Siegecraft, Two Tenth Century Instructional Manuals by “Heron of Byzantium.” Translated by Denis F. Sullivan. Washington, D.C. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. 2000. Introduction, pages 1-3.

3 Wikipedia articles on Poliorcetica and Byzantine Military Manuals

4 Sullivan, op. cit. Preface, vii.

Image credit

Based on image in: Treatises on Engines and Weapons, Italy. c. 1510. University of Glasgow Library, Special Collections Department, Book of the Month, August 2008.