Beauty: a concept of the mind that is intangible, culturally influenced, and fluid. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, say many. The realm of beauty is as old as humanity. The topic canvasses from philosophy to religion from natural to man-made. This is a huge topic, from which I will focus on the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey, and explore how people in antiquity thought about beauty. I have more questions than answers. All Butler translations are from the Sourcebook[1], and all Murray translations are from Perseus[2].

The Greek word for beautiful/beauty is not a clear cut translation:

καλὸς I. beautiful, beauteous, fair, Lat. pulcher, of outward form, Hom., etc.; καλὸς δέμας beautiful of form, Od.; so, εἶδος κάλλιστος Xen.; καλὸς τὸ σῶμα id=Xen.; c. inf., κ. εἰσοράασθαι Hom.

2. τὸ καλόν, like κάλλος, beauty, Eur., etc.: τὰ καλά the decencies, proprieties, elegancies of life, Hdt., etc.[3]

So most often καλός (kalos masculine, kalē feminine, kalon neuter) “beautiful, fair”; sometimes figuratively, but dîa for women is also translated as beautiful in the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey in Murray’s translation, as a word search indicates on Perseus, although δῖος, δῖα, δῖον (dîos/dîa/dîon) can also mean “radiant.” In the Homeric Iliad, kalos, ‘beautiful’ occurs ten times and in the Odyssey, 63 times. War does not have beautiful things, but Odysseus encountered many beautiful things on his nostos, his journey back home.

The idea of beauty is not only attached to the living; a belt or an armor can be described as beautiful, as well as a man or a woman. Yet it would be fair to start with the woman described as the most beautiful by the ancient Greeks. Her beauty “launched a thousand ships,” and her beauty was blamed for the loss of many lives.

Taking a step back, the gods also took notice of the beauty of Helen: a child of Zeus and Leda, her beauty was something out of this world. She was even offered as a prize, a prize that kindled the beginning of the end of Troy.

Aphrodite promised the most beautiful mortal to Paris. Helen was promised to him.

[25] All were of this mind save only Hera, Poseidon, and Zeus’ owl-vision daughter, who persisted in the hate which they had ever borne towards Ilion with Priam and his people; for they forgave not the wrong [atē], done them by Alexandros 29 who blamed [made neikos against] the goddesses [Hera and Athena], when they came to his courtyard, [30] but he praised her [Aphrodite] who gave him the baneful pleasure of sex.”

Iliad.24.25–30, Sourcebook

The infamous episode of the judgment of Paris is a story of a beauty contest where each contestant bribed the judge to be deemed the fairest, (kallistē) to get the apple inscribed “For the most beautiful.” Hera, Athena and Aphrodite were the contestants. The pursuit of beauty by the goddesses resulted in ugliness and despair for mortals.

The elders of Troy were also taken by the beauty of this woman. With the danger at their gates, they marveled at her presence.

150] These were too old to fight, but they were fluent orators, and sat on the tower like cicadas that chirrup delicately from the boughs of some high tree in a wood. When they saw Helen coming towards the tower, [155] they said softly to one another, “There is no way to wish for retribution [nemesis] that Trojans and strong-greaved Achaeans should endure so much and so long, for the sake of a woman so marvelously and divinely lovely.

Iliad 3.150–158, Sourcebook

Murray’s translation of 3.158, closer to the Greek, says, “wondrously like is she to the immortal goddesses to look upon.” So perhaps all goddesses are always beautiful.

How do you imagine Helen? Which depiction of her appeals to you?

The Achaeans, after libations and sacrifices to the god Apollo, also sing to appease him. They sing beautiful paeans, and Apollo enjoys the beautiful singing.

474 Thus all day long they worshipped the god with song, hymning him, 473 the young warriors of the Achaeans, singing a beautiful [kalos] paean, and the god took pleasure in his heart [phrenes] at their voices.

Iliad 1.474–475, adapted from Sourcebook

Formulaic language of the Homeric epics pays attention to beautiful body parts; from ankles to legs as in the arming scene of Alexandros. Murray’s translation and Butler’s translation differ in this passage.

δῖος Ἀλέξανδρος Ἑλένης πόσις ἠϋκόμοιο.

330 κνημῖδας μὲν πρῶτα περὶ κνήμῃσιν ἔθηκε

καλάς, ἀργυρέοισιν ἐπισφυρίοις ἀραρυίας:

Iliad 3.329–331[4]But goodly [dîos] Alexander did on about his shoulders his beautiful armour, even he, the lord of fair-haired [eukomos] Helen. [330] The greaves first he set about his legs; beautiful [kalai] they were, and fitted with silver ankle-pieces

Iliad 3.329–331 adapted from translation by Murray

while radiant [dîos] Alexandros, husband of lovely-haired [eukomos] Helen, put on his goodly armor. [330] First he covered his legs with greaves of good make [kalai] and fitted with ankle-clasps of silver

Iliad 3.329–331 adapted from Sourcebook

Different translations give a different view of understanding. Which one do you prefer? Does your preference change your view of beauty in Homeric antiquity?

Briseis laments upon seeing dead Patroklos. Lamentation is visualized by undoing the beauty.

282 Then Brisēis, looking like golden Aphrodite, 283 saw Patroklos all cut apart by the sharp bronze, and, when she saw him, 284 she poured herself all over him in tears and wailed with a voice most clear, and with her hands she tore at [285] her breasts and her tender neck and her beautiful [kala] face.

Iliad 19.282–285, adapted from Sourcebook

Along with a beautiful plane tree (kalē platanistos, Iliad 2.307), there is a beautiful golden seat (kalos thronos, Iliad 14.238), there are beautiful ankles (kallisphuros, Iliad 9.557, 9.560, Odyssey 5.333) and a beautiful neck (perikallēs deirē, Iliad 3.396), and heads with beautiful veils (kallikrēdemnoi, Odyssey 4.624).

Odysseus describes beauty in the well disposed community and also praises his host for having such a one.

[1] And resourceful Odysseus answered, “King Alkinoos, pre-eminent among all people, 3 This is indeed a beautiful thing, to listen to a singer [aoidos] 4 such as this one [= Demodokos], the kind of singer that he is, comparable to the gods in the way he speaks [audē], [5] for I declare, there is no outcome [telos] that has more pleasurable beauty [kharis] 6 than the moment when the spirit of festivity [euphrosunē] prevails throughout the whole community [dēmos] 7 and the people at the feast [daitumones], throughout the halls, are listening to the singer [aoidos] 8 as they sit there—you can see one after the other—and they are sitting at tables that are filled 9 with grain and meat, while wine from the mixing bowl is drawn [10] by the one who pours the wine and takes it around, pouring it into their cups. 11 This kind of thing, as I see it in my way of thinking, is the most beautiful thing in the whole world.

Odyssey 9.1–12, Sourcebook

Thinking about the usage of ‘beautiful’ in Murray’s translation, I wonder about his choice of translating ‘dîa‘ as “beautiful.” Murray translated ‘dîa’ as “beautiful” for a goddess. Dîa is feminine and dîos is masculine, and for ‘dîos’ he preferred ‘godly’. Butler translates dîa as ‘shining’, and dîos as ‘radiant.’

Both translations point out a quality relating to the outer, physical appearance. Do you think Homeric epic is more concerned with outer beauty?

τέτρατον ἦμαρ ἔην, καὶ τῷ τετέλεστο ἅπαντα:

τῷ δ᾽ ἄρα πέμπτῳ πέμπ᾽ ἀπὸ νήσου δῖα Καλυψώ,

εἵματά τ᾽ ἀμφιέσασα θυώδεα καὶ λούσασα.

…

275 οἴη δ᾽ ἄμμορός ἐστι λοετρῶν Ὠκεανοῖο:

τὴν γὰρ δή μιν ἄνωγε Καλυψώ, δῖα θεάων,

ποντοπορευέμεναι ἐπ᾽ ἀριστερὰ χειρὸς ἔχοντα.

Odyssey 5.262–264, 275–277In four days he had completed the whole work, and on the fifth shining [dîa] Kalypsō sent him from the island after washing him and giving him some clean clothes. … [275] she [= the star] alone has no share in the baths of Okeanos—for Kalypsō, bright [dîa] among goddesses, had told him to keep this to his left.

Odyssey 5.262–264, 275–277, adapted from SourcebookNow the fourth day came and all his work was done. And on the fifth the beautiful [dîa] Calypso sent him on his way from the island after she had bathed him and clothed him in fragrant raiment. [265] … [275] and alone has no part in the baths of Ocean. For this star Calypso, the beautiful [dîa] goddess, had bidden him to keep on the left hand as he sailed over the sea.

Odyssey 5.262–264, 275–277, Murray, Perseus translation

But for male heroes, for example Ἀγαμέμνονι δίῳ (dîos Agamemnon, dative, Iliad 2. 221) and δῖος Ὀδυσσεύς (dîos Odysseus, nominative, Iliad 2. 244), in both cases, Murray translates as “godly,” while Butler/Sourcebook translates as “radiant.” I am wondering about the relationship between beauty and being godly. Did ancient Greeks think whatever is pleasing to the eyes is also godly? Is beauty only in physical appearance or outer beauty is a reflection of inner beauty or they are the same? Is ugly bad? How about other ancient Greek sources, what does Hesiod think about beauty? Socrates is not known as beautiful, what does he or his students think about beauty? What do you think?

Until the next post, stay beautiful!

Notes

[1] Sourcebook: Homeric Iliad, Text Library Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray.

Homeric Odyssey., Text Library. Samuel Butler’s translation, revised by Timothy Power, Gregory Nagy, Soo-Young Kim, and Kelly McCray

[2] The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919.

Online at Perseus

The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924.

Online at Perseus

[3] LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon, revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940.

Online at Perseus

[4] Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

Image Credits

Judgement of Paris, Joachim Wtewael, National Gallery, public domain

Les Amours de Paris et Hélène, Jacques-Louis David, Louvre Museum, public domain

Achilles and Briseis, Naples National Archaeological Museum, public domain

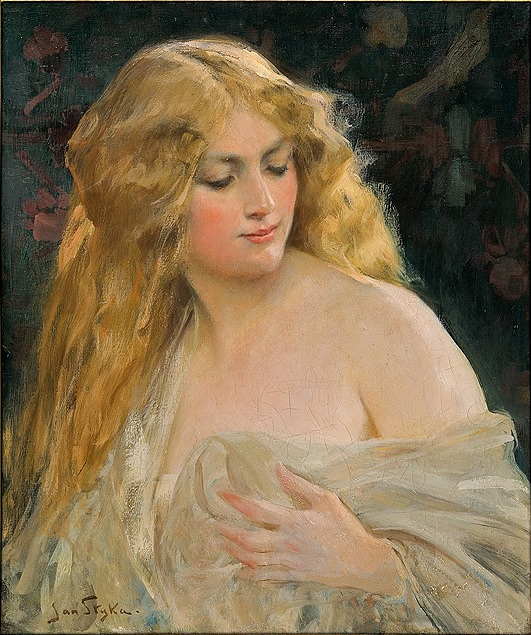

Calypso, Jan Styka, public domain

_____

Janet M. Ozsolak is a member of Kosmos Society