Who hasn’t dreamed of having a robot to accomplish certain tasks? For a long time people have conceived the existence and the possibility of having or creating such automatons, or robots, or androids or humanoids in their imaginary worlds, to replace them, or to do things in their place, or just to be with them. The word “robot” is recent (a 20th-century word), but the ancients used the word “automaton” or a periphrasis such as “looking like,” or “resembling a …,” or “having the appearance of,” “or having the learning of men.” Most of the words which we use now are recent, but the concept behind the words is old.

From Homer and Hesiod, to Aristotle and Apollodorus, and even to the real water-clocks [automatopoetasque machinas] described by Vitruvius, the ancient texts reveal some wonders about automatons. A great variety of robots are depicted, people and objects: maidens, tripods, bellows, hounds, ships, doors, soldiers, Talos the brazen man, statues of Daedalus, water clocks—and even Pandora, the first woman…

Often the god Hephaistos is named as the creator of these automatons. He is πολύφρων [poluphrōn], cunning, and also κλυτοτέχνης [klutotekhnēs]: famous in art, renowned artificer. According to Hesiod he was born to Hera without intervention from her husband Zeus. Hera was so angry as usual with her husband that she decided to have a child on her own, and of course he was a prodigy.

And Hera, without having been united in love, brought forth famous Hephaistos, as she was furious and quarrelling with her husband; Hephaistos, distinguished in crafts from amongst all the sky-born.

Theogony 929, Sourcebook

The first mention of a “wonder to behold” robot is in the Iliad; Hephaistos is working in his workshop when Thetis comes to ask him to make new weapons for Achilles, and there follows a description of twenty peculiar tripods that he is in the process of making for the gods; he had attached golden wheels to the bottom of the tripods and they would move by themselves wherever he wanted them to go and come back. Were there more than twelve Olympian gods? Why did he need twenty?

She [=Thetis] found him busy with his bellows, sweating and hard at work, for he was making twenty tripods that were to stand by the wall of his house, [375] and he set wheels of gold under them all that they might go of their own selves to the assemblies [agōn] of the gods, and come back again—marvels indeed to see. They were finished all but the ears of cunning workmanship which yet remained to be fixed to them: these he was now fixing, and he was hammering at the rivets.

Iliad 18.373–380, Sourcebook

His bellows are also automated, and, like the tripods, do not think by themselves but obey Hephaistos:

When he had so said he left her and went to his bellows, turning them towards the fire and bidding them do their office. [470] Twenty bellows blew upon the melting-pots, and they blew blasts of every kind, some fierce to help him when he had need of them, and others less strong as Hephaistos willed it in the course of his work.

Iliad 18.468–472, Sourcebook

But the god has also female robots made of gold to help him. They look like women and they know what to do by themselves. We might say that he was an inspiration for the creator of Goldfinger and other people obsessed with robots or gold. He also was the father of artificial intelligence in a way, since his specific handmaids had some type of artificial intelligence, they were able to reason, think, talk and had knowledge like gods.

There were golden handmaids also who worked for him, and were like real young women, with sense and reason [noos], voice also and strength, [420] and all the learning of the immortals; these busied themselves as the king bade them…

Iliad 18.417–421, Sourcebook

There are also mentions of automated doors in the Iliad. It’s not specified if Hephaistos built or invented them, but he built all the gods’ houses so he might be the creator of doors that know when to open and close, in a mysterious manner, very handy for Hera.

Hera lashed her horses, and the gates of the sky bellowed as they flew open of their own accord—gates over which the Seasons [hōrai] preside, in whose hands are the sky and Olympus, either [395] to open the dense cloud that hides them or to close it.

Iliad 5.745 and also 8.391, Sourcebook

Another object endowed with some type of artificial intelligence is described in the Odyssey: the Phaeacians’ ships. They have knowledge, they think and are able to avoid danger, they know what men are thinking about and what men want them to do. They can act in a rational way, and take the best decisions.

For the Phaeacians have no pilots; their vessels have no rudders as those of other nations have, but the ships themselves understand what it is that we are thinking about and want; [560] they know all the cities and countries in the whole world, and can traverse the sea just as well even when it is covered with mist and cloud, so that there is no danger of being wrecked or coming to any harm.

Odyssey 8.558-562, Sourcebook

Automated immortal watchdogs are also invented by Hephaistos for the Phaeacians; their role was limited to watching over the palace.

On either side there stood gold and silver mastiffs which Hephaistos, with his consummate skill, had fashioned expressly to keep watch over the palace of great-hearted king Alkinoos; so they were immortal and could never grow old.

Odyssey 7. 90-95, Sourcebook

Another myth about other robots is told by Apollodorus. From the teeth of the dragon killed by Cadmus some soldiers, the Sparti, came out. However the automatons, killer robots, were not very efficient, certainly not equipped with thinking, and killed each other.

In his indignation Cadmus killed the dragon, and by the advice of Athena sowed its teeth. When they were sown there rose from the ground armed men whom they called Sparti. These slew each other, some in a chance brawl, and some in ignorance. But Pherecydes says that when Cadmus saw armed men growing up out of the ground, he flung stones at them, and they, supposing that they were being pelted by each other, came to blows. However, five of them survived, Echion, Udaeus, Chthonius, Hyperenor, and Pelorus. But Cadmus, to atone for the slaughter, served Ares for an eternal year; and the year was then equivalent to eight years of our reckoning.

Apollodorus, Library 3.4, translated by Sir James George Frazer

Apollodorus also recounts the sad story of a very tall automaton, the famous Talos, another creation of Hephaistos. This robot was very special, he was tall, and in charge of protecting the island of Crete from invaders by throwing rocks at them. He had only a vein filled with ichor [blood of the immortals] and a nail was keeping the vein shut. Hephaistos had a very creative mind. All his inventions were original and one of a kind.

Putting to sea from there, they were hindered from touching at Crete by Talos. Some say that he was a man of the Brazen Race, others that he was given to Minos by Hephaestus; he was a brazen man, but some say that he was a bull. He had a single vein extending from his neck to his ankles, and a bronze nail was rammed home at the end of the vein. This Talos kept guard, running round the island thrice every day; wherefore, when he saw the Argo standing inshore, he pelted it as usual with stones. His death was brought about by the wiles of Medea, whether, as some say, she drove him mad by drugs, or, as others say, she promised to make him immortal and then drew out the nail, so that all the ichor gushed out and he died. But some say that Poeas shot him dead in the ankle.

Apollodorus, Library 9.26

What a sad ending for this tall brazen man!

Hephaistos, the prodigy son of Hera, also created some type of gynoid, a feminine humanoid robot. Was it really a gynoid robot since she was the first mythological woman, named Pandora, the very one who gave birth to humanity (by giving birth to one daughter, named Pyrrha, according to Apollodorus, Library 1.7) in a myth? Was she at the root of the invention of what we now call a humanoid? Have humans in our century surpassed Hephaistos or are they still trying hard to create human-like creatures?

Then he ordered Hephaistos, renowned all over, to shape some wet clay as soon as possible, and to put into it a human voice and strength, and to make it look like the immortal goddesses, with the beautiful and lovely appearance of a virgin.

Hesiodic Works and Days 60–63, Sourcebook

It all seems so easy for the god, who even inspired Aristotle, who dreamed of a world filled with automatons like the ones in the workshop of Hephaistos or like the statues created by Daedalus.

In Politics, he imagines a world where people would not need slaves but automatons would be used instead of humans.

…property generally is a collection of tools, and a slave is a live article of property. And every assistant is as it were a tool that serves for several tools; for if every tool could perform its own work when ordered, or by seeing what to do in advance, like the statues of Daedalus in the story *, or the tripods of Hephaestus which the poet says ‘enter self-moved the company divine,’—if thus shuttles wove and quills played harps of themselves, master-craftsmen would have no need of assistants and masters no need of slaves.

Aristotle, Politics 1.1253b, translated by H. Rackham

* H. Rackham has the following note about the statues from Plato’s Meno. [* This legendary sculptor, Daedalus, first represented the eyes as open and the limbs as in motion, so his statues had to be chained to prevent them from running away. Plat. Meno 97d)]

Aristotle ’s view of slaves, “a slave is a live article of property,” is problematic, and he coldly asserts the fact that it just would be nice not to need slaves.

Last, we leave the mythological world with a real automated instrument described by Vitruvius, in his book about architecture. He depicts a water clock made by Ctesibius, a Greek inventor (285–222 BCE):

Methods of making water clocks have been investigated by the same writers, and first of all by Ctesibius the Alexandrian, who also discovered the natural pressure of the air and pneumatic principles….

He also devised methods of raising water, automatic contrivances, and amusing things of many kinds, including among them the construction of water clocks automatopoetasque machinas.Vitruvius The Ten Books on Architecture 9.8.4-7, translated by Morris Hicky Morgan

Bibliography

Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook: Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English. Gregory Nagy. 2013.

https://chs.harvard.edu/book/the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours-sourcebook/

Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Sourcebook: Odyssey Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Sourcebook Theogony 1–115: Translated by Gregory Nagy; 116–1022: Translated by J. Banks. Adapted by Gregory Nagy

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Sourcebook Hesiodic Works and Days Translated by Gregory Nagy

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Apollodorus Library: English and Greek texts: Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer’s notes.

Online at Perseus

Aristotle Politics: Aristotle in 23 Volumes, Vol. 21, translated by H. Rackham.

Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1944.

Online at Perseus

Vitruvius: The Ten Books on Architecture. Vitruvius. Morris Hicky Morgan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. London: Humphrey Milford. Oxford University Press. 1914.

Online at Perseus

Image credits

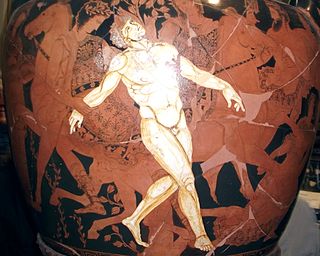

Foundry Painter: Hephaistos hands the new armor of Achilles to Thetis. 490–480 BCE.

Photo: Bibi Saint-Pol. Public domain, via Wikimedia Common

Luca Giordano: The Forge of Vulcan

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Claude Lorrain: Port Scene with the Departure of Odysseus from the Land of the Phaeacians

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Talos. Attributed to Talos Painter. Red-figure Athenian krater 425 to -375 BCE (attribution by Beazley 217518)

Photo: Forzaruvo94. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license, via Wikimedia Commons

Talos. Silver didrachm from Phaistos, Crete (ca. 300/280-270 BCE), obverse

Photo: Jastrow. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

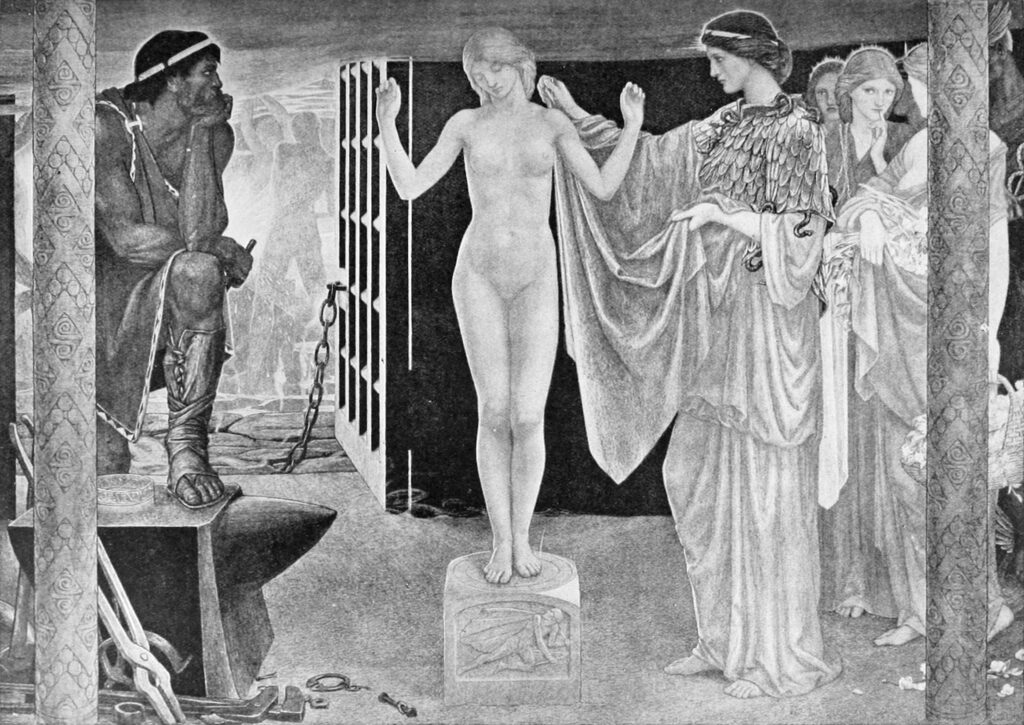

John D. Batten: Pandora. 1913.

Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hydraulic clock of Ctesibius, reconstruction at the Technological Museum of Thessaloniki

Photo: Gts-tg. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license, via Wikimedia Commons

Hélène Emeriaud is a Team member at HeroesX, a MOOC on edX. She studied ancient Greek at school in France and for several years at the University of Minnesota. She holds a degree in Education from Montreal University, and a Master of Education from McGill University. She is an active participant and member of the Editorial Team in the Kosmos Society with a particular interest in ancient Greek and Latin language learning.