For centuries of European art, it was one of the most frequently portrayed moments from classical antiquity. Wikimedia Commons includes more than fifty artistic renderings of an apocryphal meeting of the young Alexander of Macedonia (later to be known as “the Great”) and the much older Diogenes of Sinope (later to be known as “the Cynic”).

It is hard to imagine a more unlikely pair. Alexander was the brash young king of Macedonia, who had conquered Greece and was on his way to conquering the world. He can be assumed to have been dressed at the time of the meeting in regal attire befitting his status and to have been accompanied by a retinue of attendants.

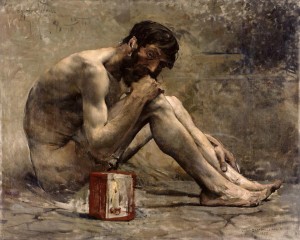

Diogenes was the antisocial, ascetic philosopher who lived in a barrel and rejected all of the norms of civilized behavior. He is usually portrayed as almost naked and unkempt, with long hair and a beard. It was widely known that he urinated, defecated, and masturbated in public, to show his contempt for the conventions of society. Caricatures of him in later times often included a lighted lamp that he is said to have carried even in the daytime, as he went in futile search for an honest man.

The brief encounter of the two is generally said to have taken place in Corinth, where Diogenes lived in his later years. The only occasion on which Alexander visited Corinth was soon after the death of his father in 336 BCE. Alexander would have been twenty at the time, and Diogenes would have been around seventy. Different versions of the story of the meeting are found in various ancient sources,* most notably in Plutarch’s Life of Alexander (at 14) and Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (at 6.38).

The brief encounter of the two is generally said to have taken place in Corinth, where Diogenes lived in his later years. The only occasion on which Alexander visited Corinth was soon after the death of his father in 336 BCE. Alexander would have been twenty at the time, and Diogenes would have been around seventy. Different versions of the story of the meeting are found in various ancient sources,* most notably in Plutarch’s Life of Alexander (at 14) and Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (at 6.38).

Most likely Alexander was well aware of who Diogenes was. The philosopher had supposedly been taken captive by his father King Philip II during an earlier campaign against the Greeks. According to Plutarch (at Moralia 70d), upon being asked by Philip whether he was a spy, Diogenes had said, “I most certainly am a spy, Philip. I spy on your absence of wisdom and common sense, which is the only thing forcing you to go and gamble your kingdom and your life in a single moment.”

According to Epictetus in his Discourses (at 3.22.92), at the time of the encounter in Corinth, Diogenes was asleep when Alexander approached. Alexander, who was an enthusiastic reader of the Iliad, is said to have quoted a line (2.24) spoken by the divine Dream to Agamemnon: “To sleep the whole night through ill befits a man of counsel.” Diogenes, awakening, countered by quoting the very next line while still half-asleep, “Who has people to watch over and a multitude of cares.”

According to Diogenes Laertius in his life of Diogenes (at 6.60), Alexander stood over the philosopher and said, “I am Alexander the great king.” To which Diogenes responded, “I am Diogenes the dog.” When Alexander asked what he had done to be called a dog, he said, “I fawn on those who give me anything, I yelp at those who refuse, and I set my teeth in rascals.”

In the most famous exchange of the meeting, Alexander asked Diogenes whether there was anything he could do for him. Diogenes, who was enjoying the warmth of the autumn sun, answered, “Stand aside to stop blocking the sun.” This abrupt response, showing his utter contempt for the power and prestige that Alexander craved, spawned the large number of artistic renderings that followed.

In the most famous exchange of the meeting, Alexander asked Diogenes whether there was anything he could do for him. Diogenes, who was enjoying the warmth of the autumn sun, answered, “Stand aside to stop blocking the sun.” This abrupt response, showing his utter contempt for the power and prestige that Alexander craved, spawned the large number of artistic renderings that followed.

Although Alexander’s attendants took umbrage at Diogenes’ rudeness to their king, Alexander himself was not displeased. Leaving, he is said to have remarked, “If I were not Alexander, I would want to be Diogenes.”

In spite of his antisocial behavior, Diogenes’ influence in ancient philosophy was enormous. Along with his teacher Antisthenes, he was the founder of an influential school of philosophy known as the Cynics. The name of the school comes from the Greek adjective κυνικός (kunikos), meaning “dog-like,” after the Greek noun for dog κύων (kuōn, genitive kunos).

The reason for the name Cynics is uncertain. Naturally it has been assumed to come from Diogenes’ animalistic manner of living, but more likely it came from the location of the philosophic school in the Cynosarges area of Athens. A well-known 1848 painting by Edwin Landseer even portrayed Diogenes and Alexander as dogs (reportedly* the inspiration for Walt Disney’s The Lady and the Tramp).

The reason for the name Cynics is uncertain. Naturally it has been assumed to come from Diogenes’ animalistic manner of living, but more likely it came from the location of the philosophic school in the Cynosarges area of Athens. A well-known 1848 painting by Edwin Landseer even portrayed Diogenes and Alexander as dogs (reportedly* the inspiration for Walt Disney’s The Lady and the Tramp).

Legend has it that Diogenes and Alexander died on the same day in 323 BCE, one having conquered the world and thereby extended the reach of Greek civilization, the other having subverted the norms of civilized society altogether. Their brief meeting was captured in a famous bas-relief sculpture by Pierre Puget from ca. 1680, now in the Louvre.

*For full citations to the many ancient sources and modern references, see https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diogenes_and_Alexander#

Image credits

Jacques Gamelin, “Alexandre et Diogène,” 18th century.

Jules Bastien-Lepage, “Diogenes,” Musée Marmottan, Paris, 1905.

Nicolas-André Monsiau, ”Alexander and Diogenes”, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen, France, 1818.

Edwin Henry Landseer, “Alexander and Diogenes,” Tate Collection, London, 1848.

Pierre Puget, Musée du Louvre, vers 1680.

Bibliography

Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, vol. 2, trans. by R.D. Hicks (Witch Books, 2011).

Epicurus, Discourses, Fragments, and Handbook, trans. by Robin Hard, Oxford, 2014.

Plutarch, Essays, trans. by Robin Waterfield, Penguin, 1992.

Plutarch, Greek Lives, trans. by Robin Waterfield, Oxford, 2008.

___

Laura Ford (“Tritogeneia”) is a once and future classicist who has combined a lifelong interest in Greek literature and philosophy with a career in law, higher education administration, and private school teaching. Now retired, she lives in central Virginia.