Aeacus [Aiakos] while he reigned in Aegina was renowned in all Greece for his justice and piety, and was frequently called upon to settle disputes not only among men, but even among the gods themselves.[1]

Whether Aiakos actually settled disputes among the gods themselves is supported by Pindar when referring to the nymph Aegina who “…bore Aeacus [Aiakos], the dearest of all men on earth to the loud-thundering father. Aeacus [Aiakos] settled disputes even for the gods.”[2]

But in all of Greek myth I can find no specific details of brilliant Aiakos settling disputes among the immortals. An example of him settling disputes among men comes from Pausanias:

…Skiron [King of the Megarians] married the daughter of Pandion and afterwards disputed with Nisos, the son of Pandion, about the throne, the dispute being settled by Aiakos, who gave the kingship to Nisos and his descendants, and to Skiron the leadership in war.[3]

This might be a fine example of Aiakos’ skill as a mediator among mortals, but still not an example of Aiakos as judge among the divinities. It does remind me however of Briareos, the Hundred-Hander, when he mediated the claims of Helios and Poseidon for Corinth:

…The Corinthians say that Poseidon had a dispute with Helios about the land, and that Briareos arbitrated between them, assigning to Poseidon the Isthmus and the parts adjoining, and giving to Helios the height above the city [the Acropolis of Corinth].[4]

The nice thing about Briareos’ judgment is it gives to each god what most rightly would be associated with him: the sea-god Poseidon gets the watery channel and low-lying land, and the Titan of the Sun gets that portion of the community closest to his realm in the sky, the acropolis. The truly marvelous thing about Briareos’ wise judgment among the gods in sharp contrast to other divine judgments is that afterwards no one’s wings got torn off as in the case of the dispute between the Sirens and the Muses[5]; no one’s river beds dried up as was the case when the Argive river-gods judged in Hera’s favor[6]; and unlike in the contest between Apollo and Marsyas, with Briareos’ judgment above no one was skinned alive afterwards.[7]

Assuming Aiakos made similar Solomon-like judgments among the gods, what were they? I propose two disputes we know he was involved in. Maybe his involvement hints at the notion he was the mediator in each case.

- The marriage of Thetis

- The revolt of Poseidon and Apollo against Zeus

The marriage of Thetis

…when Zeus and splendid Poseidon contended for marriage with Thetis, each of them wanting her to be his lovely bride…[8]

Now admittedly Pindar gives Themis all the credit for judging between the two and picking a mortal as the nymph’s husband. And according to Aeschylus, maybe it was Prometheus that made them see the light.[9] But still the choice of Aiakos’ son Peleus as the spouse of the Nereid, must if not indicate involvement at least indicate close association with all involved.

The revolt of Poseidon and Apollo against Zeus

Most famously, the sea-nymph Thetis, daughter-in-law of Aiakos and Briareos squashed a revolt against Zeus on Olympus as related by her son Achilles:

Often in my father’s house have I heard you glory in the fact that you alone of the immortals saved the son of Kronos from ruin, when the others, with Hera, Poseidon, and Pallas Athena would have put him in bonds. It was you, goddess, who delivered him by calling to Olympus the hundred-handed monster whom gods call Briareus, but men Aigaion, for he is has more force [biē] even than his father Uranus; [10]

As a result of this revolt—or another—we hear how Poseidon and Apollo suffered as common workmen for a mortal king. Poseidon speaks of this experience repeatedly in the Iliad but most extensively here to Apollo:

…we two alone of all the gods fared hardly round about Ilion when we came from Zeus’ house and worked for Laomedon a whole year at a stated wage and he gave us his orders. I built the Trojans the wall about their city, so wide and fair that it might be impregnable,[11]

So who mediated this solution to their strife? There is no reference to Themis intervening. Could it have been Aiakos again?

…Aeacus, whom wide-ruling Poseidon and the son of Leto, when they were about to build the crown of walls to encircle Ilium, summoned as a fellow worker[12]

All this is pure speculations on my part! But, if some ancient forgotten legends say Aiokos settled disputes among the gods I judge two of the disputes were over:

- the hand of “a girl, just one girl” and

- a revolt against Zeus

Has anyone got other suggestions?

References

[1] “Aeacus” William Smith ed. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. London. John Murray: printed by Spottiswoode and Co., New-Street Square and Parliament Street. In the entry “Soranus,” we find: “at this present time (1848)” and this date seems to reflect the original date of the work cited. 1873—probably the printing date.

[2] Pindar Isthmian 8.21–24, Odes. Pindar. Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990. Thanks to Perseus.

[3] Pausanias Description of Greece 1.39.6 Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy.

[4] Pausanias, Description of Greece 2.1.6, Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy.

[5] Pausanias Description of Greece 9.34.3, Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy.

[6] Pausanias Description of Greece 2.15.5. Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy.

[7] Apollodorus Bibliotheca 1.4.2, Apollodorus. The Library. Translated by Sir James George Frazer. Loeb Classical Library Volumes 121 & 122. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921.

[8] Pindar, Isthmian 8.27–28 Odes, Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

[9] Aeschylus Prometheus Bound 907–914. Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. 1. Prometheus Bound. Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph.D. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1926.

[10] Iliad 1.396–404 Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power

[11] Iliad 21.443–447, Homeric Iliad Translated by Samuel Butler Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power

[12] Pindar Olympian 8.31–34, Odes, Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

Image credits

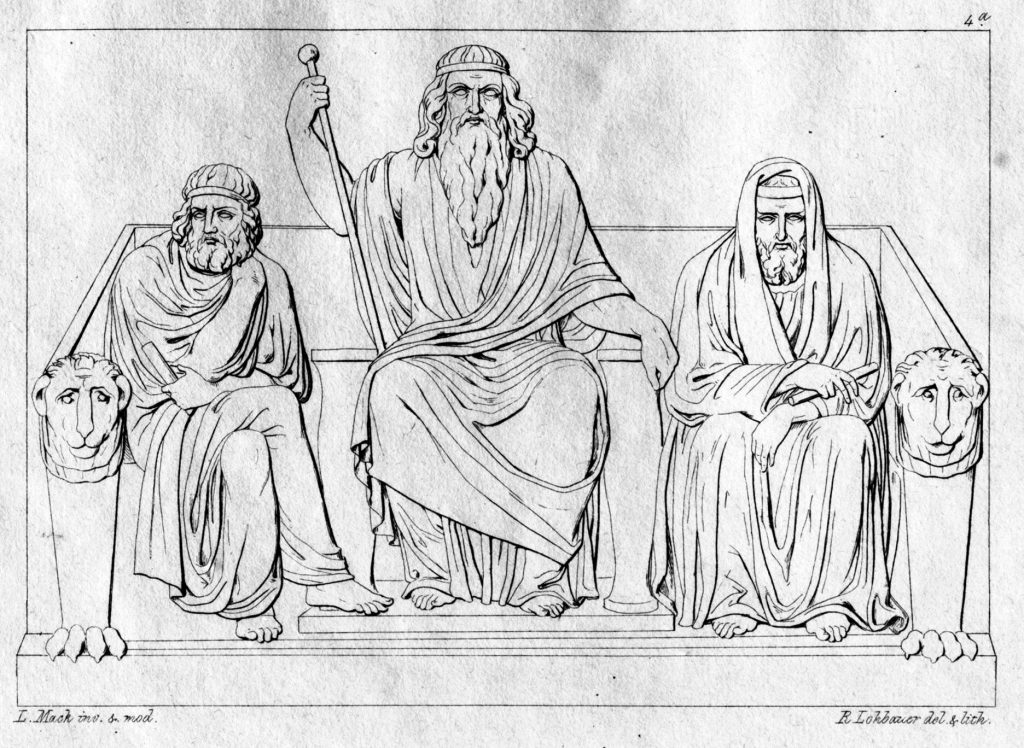

Ludwig Mack: The Underworld, showing Aiakos with the judges, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune: Telamon and Aiakos public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Tommaso Prioli, after John Flaxman: Thetis and Briareus, Wikimedia Commons CC BY 3.0

Bill Moulton is a life-long independent researcher in Greek Mythology, starting in fourth grade when his fondness for the topic threw off the grading curve. Bill is a graduate of HeroesX and active with Kosmos Society. He blogs and tweets on Classical Studies.