~ A guest post by Jenna Cole ~

While thinking about oinops in the course of our word study, one passage stood out as unusual because oinops appears in one published edition of the Greek Iliad text but not in another. For Scroll I, line 350, Chicago Homer, which is based on the 1902 Oxford edition by D.B. Munro, gives this:

θῖν’ ἔφ’ ἁλὸς πολιῆς, ὁρόων ἐπὶ οἴνοπα πόντον:

But Perseus, which is based on a later Oxford edition, has this:

θῖν᾽ ἔφ᾽ ἁλὸς πολιῆς, ὁρόων ἐπ᾽ ἀπείρονα πόντον:

The two Greek words in bold are forms of οἶνοψ [oinops, ‘wine-faced’] and ἀπείρων [apeirōn, ‘boundless, limitless’]. The use of these two Greek words can be seen in different English translations; some will use ‘wine-dark’ sea while others use ‘boundless’ sea.

What is this reason for this difference?

During the first version of HeroesX, I posted about an article by Caroline Alexander in Lapham’s Quarterly, which states “The rendering of ‘winelike’ here is based on a new edition of the Greek text of The Iliad, first published in 1998. Instead of oínopa, earlier editions had apeírona, ‘infinite, boundless’ sea, which was followed in almost all previous translations.”

In response to my post, Lenny Muellner provided this clarification:

[T]he text of Homeric poetry is not a fixed text, and in the example you give of Iliad 1 line 350, the change in the text from apeirona ponton ‘limitless sea’ to oinopa ponton did not happen in 1998. It’s an ancient variant in the formulas for that line and many others, and the famous Alexandrian editor of the Homeric text, Aristarchus, read apeirona ponton in that place, and the two words also appear together in a different expression in Odyssey 4 line 510 (there’s also the expression apeiron gaian ‘limitless earth’). So we can’t just pick and choose which one to read: both of them are legitimate and reflect the traditional diction.

I knew to expect multiformity of epic based on the oral tradition, but Lenny’s reply really opened my eyes to the importance of presenting and reading texts of the Iliad and Odyssey in a way that reflects this multitextuality. This is necessary because both adjectives are part of the Homeric tradition.

I wondered if I might be able to see any of this evidence of multitextuality, which led me to the Homer Multitext project. For some background on the project, and the concept of multitextuality, read Gregory Nagy’s article titled “The Homer Multitext Project”, which is freely available on the Center for Hellenic Studies website.

Here is a paragraph from the Homer Multitext project website that summarizes their goals:

The Homer Multitext project seeks to present the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey in a critical framework that accounts for the fact that these poems were composed orally over the course of hundreds, if not thousands of years by countless singers who composed in performance. The evolution and the resulting multiformity of the textual tradition, reflected in the many surviving texts of Homer, must be understood in its many different historical contexts. Using technology that takes advantage of the best available practices and open source standards that have been developed for digital publications in a variety of fields, the Homer Multitext offers free access to a library of texts and images and tools to allow readers to discover and engage with the Homeric tradition.

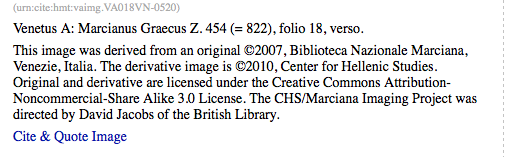

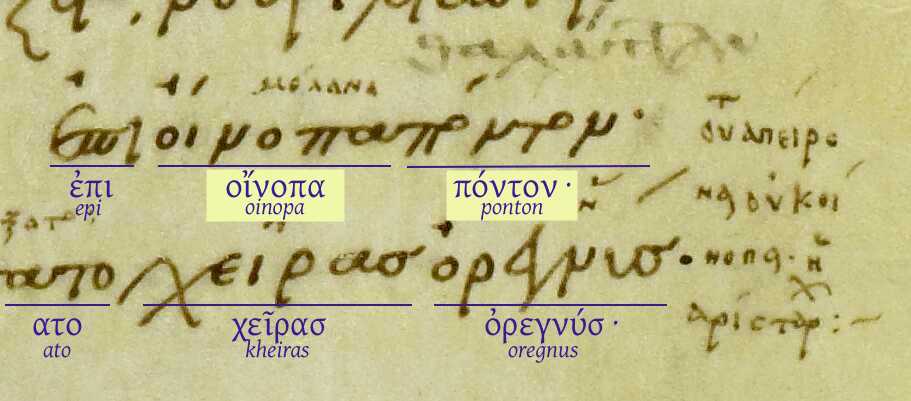

It was on the Homer Multitext website that I was able to locate the image at the top of this post, which comes from the Venetus A, a 10th century manuscript that contains the entire Iliad and associated commentary. For more information about the manuscript, see this article by Casey Dué and Mary Ebbott on the CHS website. At the end of this post, I provide a brief explanation on how I used the Homer Multitext Manuscript Browser and other resources, but first I would like to look at what is observable in the image at the top of this post.

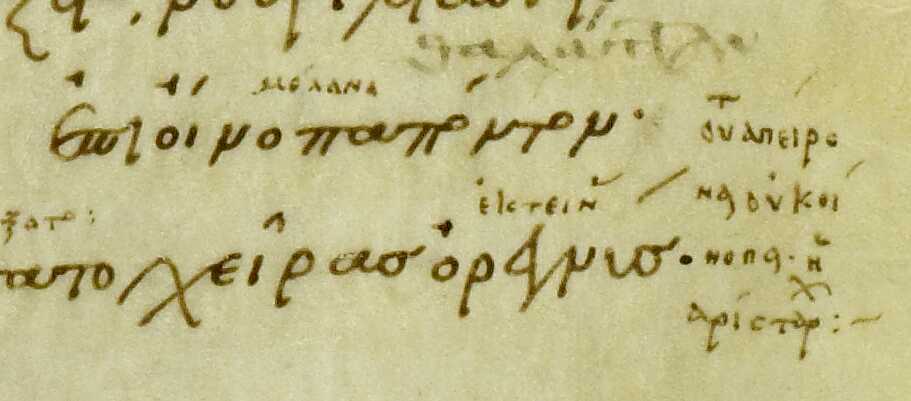

The main text that you can see in the image at top is:

…ἐπι οἴνοπα πόντον·

…[ἠρήσ]ατο χεῖρας ὀρεγνύς·

Lines 350 and 351 of Iliad I can be transliterated and translated as (the portion of the text that is visible in the image above is underlined):

thin’ eph halos poliēs, oroōn epi oinopa ponton

polla de mētri philē ērēsato kheiras oregnusthe shore of the grey sea, looking out upon the wine-faced sea.

He raised his arms in prayer to his dear mother

You will recall this scene in Iliad Scroll I when Achilles goes to the shore of the sea to pray to his mother Thetis following his conflict with Agamemnon.

Can you see the ἐπι in the image at the top of the post? I ask because, though I enjoy looking at this beautiful, handwritten script, I find it a little hard to read the text. To me, the ἐπι looks a bit like a capital ‘C’, then a ‘w’ with a line over it, that connects to an ‘i’ on the right and back to the ‘C’ on the left. Also, it appears that the scribe didn’t always use spaces to separate words, so the next word, οἴνοπα, begins immediately following ἐπι. The researchers – including undergraduate students as well as professors – at Homer Multitext have deciphered this handwriting, which looks different than our modern fonts, and have posted their transcriptions and research online. In the image below, I have marked off the words in Greek and transliterated Latin letters. Note that the manuscript uses a final σ, not ς.

There are other groups of words called ‘scholia’ – marginal notes, especially those made by ancient grammarians on classical passages – around the main text on the manuscript. On the right-hand side, in smaller letters, is this marginal text:

οὕαπείρο

ναοὐκοί

νοπα·ἡ

Αριστάρ

The scholia are small and hard to read because they often lack spaces between words and lines. The good people at Homer Multitext are transcribing scholia, and in this case they have:

οὕτως απείρονα οὐκ οίνοπα · ἡ Αριστάρχου ⁑

which can be roughly translated to ‘thus apeirona not oinopa, according to Aristarchus’.

Wow! So here, in a 10th century manuscript, we have a reference to commentary by Aristarchus, famed Homeric editor and librarian at Alexandria, displaying multiformity of the Homeric Iliad. The focus of our word study has been οἶνοψ [oinops], but there is clearly room for studying its variant, ἀπείρων [apeirōn], and its meaning within the ancient Greek poetic tradition.

And there is something else relevant to our word study: another bit of tiny text, squeezed between lines, located just above the word oinopa, reads:

μέλανα

Melana is a form of μέλας [melas, ‘black, dark’].

Could this mean what I think it means? Are we seeing evidence for that poetic, but not literal, translation of oinopa ponton as ‘wine-dark sea’? I don’t know the answer; I don’t know what scholars think of this. I looked through images of the Venetus A to see if there were other scholia associated with oinops, but I did not find any. So for the time being, in my mind, this tiny bit of text has lent support in Greek to a phrase that for many English speakers is connected with Homer and the ancient Greeks. I think that is kind of awesome!

How I Found My Evidence with Homer Multitext

Below is a step-by-step description of how I found the image at the top of this post and learned more about the text it captures. Note that the captions beneath the screenshots provide hyperlinks to those pages on Homer Multitext.

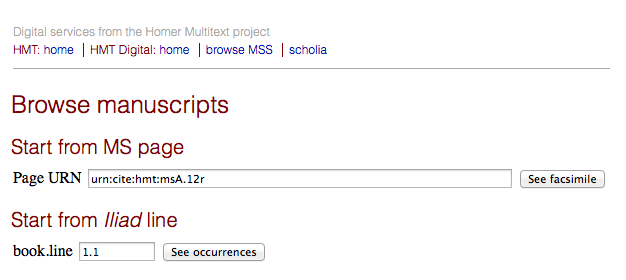

Starting on the Homer Multitext website, click ‘MS Browser’ at the top of the page. This takes you to a new search page:

Homer Multitext Browse manuscripts search page

Homer Multitext Browse manuscripts search page

If you have a specific section of the text that you would like to explore, as I did, enter the location as book number [dot] line number in the text field under ‘Start from Iliad line’. I entered 1.350 to call up Iliad Scroll I, line 350. Then press the button ‘See occurrences’.

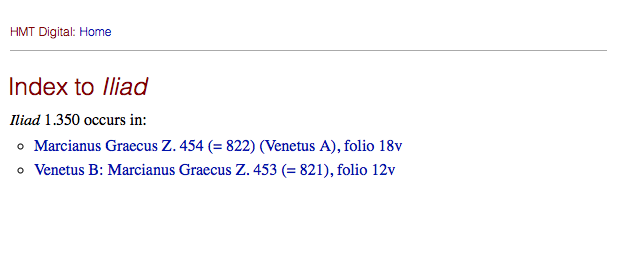

Homer Multitext HMT Digital: Index to Iliad page

Homer Multitext HMT Digital: Index to Iliad page

This is the ‘HMT Digital: index to Iliad‘ page. Clicking on the first line takes you to the appropriate page in the Venetus A.

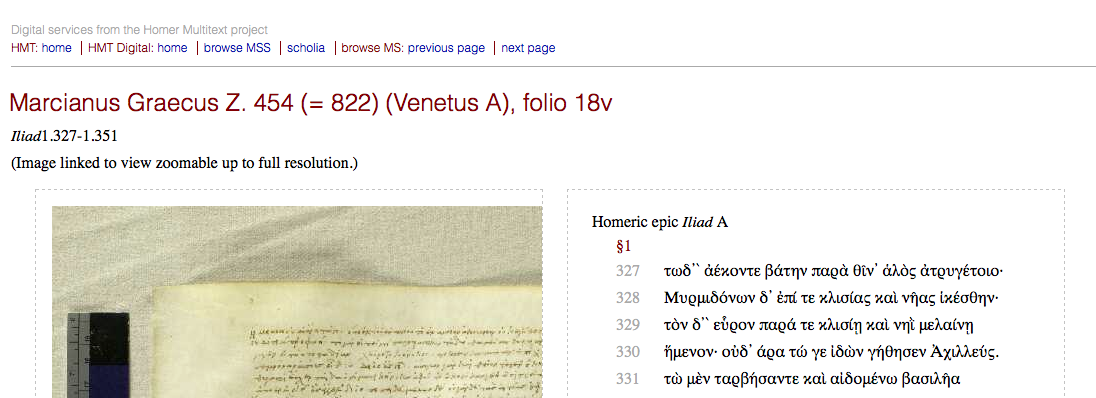

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital: facsimile reader

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital: facsimile reader

This is the ‘HMT Digital: facsimile reader‘. The page contains an image of the manuscript itself on the left-hand site, and transcribed Greek with line numbers on the right-hand side. If you would like to zoom in on the image, click on it and you will be brought to a new page with controls that look like this:

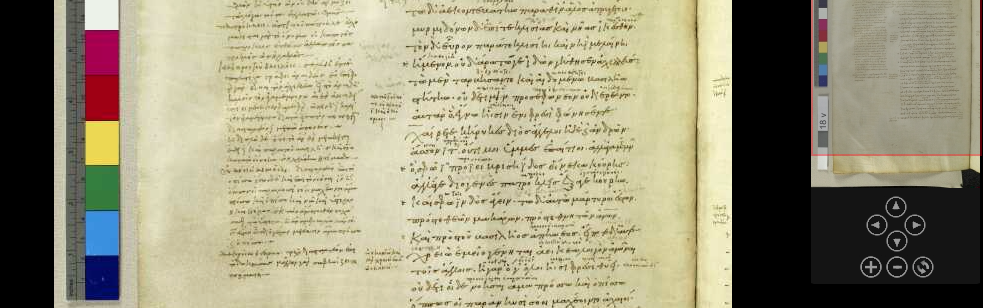

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital: facsimile reader: zoomable image page

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital: facsimile reader: zoomable image page

On this zoomable image page, you can use the arrow and zoom button to control your view, or can double-click to zoom and click-and-drag to move around on the image.

Selecting an image

If you would like to select a portion of the manuscript that is citable so that other people can locate it with a standard reference, use your back arrow to return to the HMT Digital: facsimile reader. Scroll all the way down to the bottom and you will see the following text:

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital: facsimile reader: citation section of page

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital: facsimile reader: citation section of page

Click on ‘Cite & Quote Image’ and you will be taken to a new page.

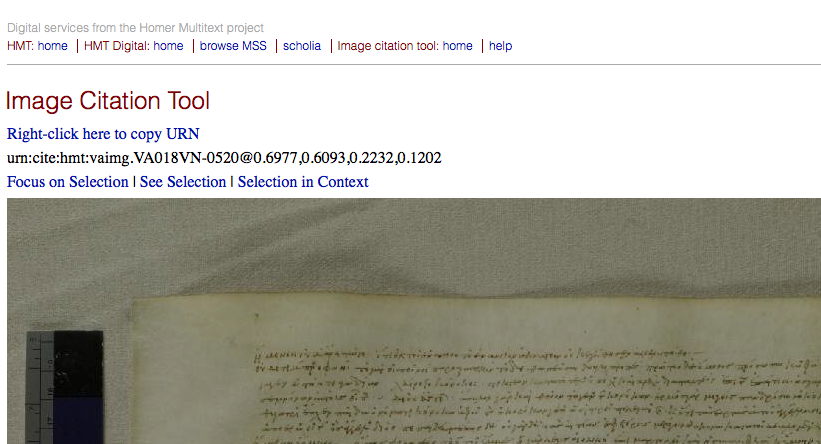

Homer Multitext: Image Citation Tool

Homer Multitext: Image Citation Tool

Now you are at the Homer Multitext: Image Citation Tool. You can scroll around to find the portion of the document that you want. Click-and-drag your cursor to highlight a portion of the image, which you will see zoomed in at the top-right portion of the webpage. This area is called the Region of Interest. Click inside the box to drag the Region of Interest around. Drag the edges of the selected Region of Interest to change its dimensions.

If you would like to see a larger image of the region that you have selected, go to the top of the page and click ‘Focus on Selection’. If you click on that image, you can also create a smaller selected region. Once you are happy with the selected region, you need to copy the URN. This URN is the code that you can use to cite this exact portion of the manuscript image that you are interested in and wish to share with others. Right-click on ‘Right-click here to copy URN’ and then paste it into your document. Here is my URN:

urn:cite:hmt:vaimg.VA018VN-0520@0.7424,0.6437,0.1679,0.0555

To save your image, click on ‘See Selection’ and you will be taken to a new page that contains an image of the Region of Interest that you selected. You can then right-click to download or save that image to your computer.

Exploring scholia

I have already shown that the HMT Digital: facsimile reader presents a transcription of the Greek text of the Iliad on the right-hand side of the webpage. Note, however, that this transcription does not include scholia. There are different types of scholia in the Venetus A, including marginal and interlinear.

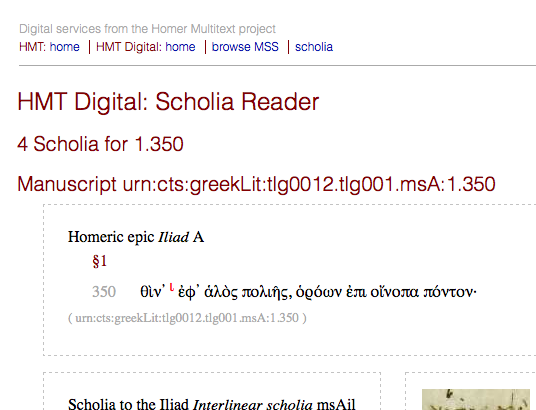

To explore these, go to the search page on the Homer Multitext site: http://beta.hpcc.uh.edu/tomcat/hmt-digital/ . There is a section called ‘Read scholia’. To use this, you must enter the text URN that you want to explore. The field is already pre-filled with the following text: urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0012.tlg001.msA:1.1

This URN will take you to msA [Venetus A, Iliad] 1.1 [Scroll I, line 1]. I modified this URN to: urn:cts:greekLit:tlg0012.tlg001.msA:1.350 , since I was interested in Iliad I, line 350. Then press ‘See texts’.

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital Scholia Reader

Homer Multitext: HMT Digital Scholia Reader

Scrolling down, you can see four occurrences of scholia associated with Iliad I, line 350. There are notes associated with these occurrences, and sometimes the Greek is transcribed. This is what is provided for the scholia about Aristarchus:

Scholia to the Iliad Interior scholia msAint

§1

§943

οὕτως απείρονα οὐκ οίνοπα · ἡ Αριστάρχου ⁑

( urn:cts:greekLit:tlg5026.msAint.hmt:1.943 )

There is also an image of the relevant region from the manuscript, and an image URN that you can reference. Note that literature URNs contain ‘greekLit’, while image URNs contain ‘img’.

Searching by URN

If you have a reference to a URN that you would like to see, you can go to the HMT Digital: lookup by URN page: http://beta.hpcc.uh.edu/tomcat/hmt-digital/svcforms. Under ‘Examples: see details’ you can enter URNs for images, passages, and other objects. Be sure to paste the whole URN, including the ‘urn:’ prefix.

Comments:

If you would like to comment on this post, members please join in the discussion in the forum.

UPDATE: March 2021. The techniques for displaying the images were based on a beta version of the Homer Multitext site as it was in August 2014. Some links may no longer be active, and the navigation on that site may have changed.

Homer Multitext home page

Homer Multitext home page