~ A guest post by Jenna Cole and the Oinops Study Group ~

I can remember when I first became intrigued by the Greek word oinops, at the very end of the first offering of HeroesX. In Hour 24 of the Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours (H24H), the Homeric Hymn (7) to Dionysus was given as Hour 24 Text C, which begins as follows:

|1 About Dionysus son of most glorious Semele |2 my mind will connect, how it was that he made an appearance [phainesthai] by the shore of the barren sea |3 on a prominent headland, looking like a young man |4 at the beginning of adolescence. Beautiful were the locks of hair as they waved in the breeze surrounding him. |5 They were the color of deep blue. And a cloak he wore over his strong shoulders, |6 color of purple. Then, all of a sudden, men seen from a ship with fine benches |7 — men who were pirates — came into view, as they were sailing over the wine-colored [oinops] sea [pontos].[1]

Just these first seven lines of the poem captivated me – Dionysus’ blue hair and purple cloak, pirates, and sailing a wine-colored sea. It was there that I saw the word oinops – this word of diverse translations – sometimes appearing as ‘wine-dark,’ or ‘wine-blue,’ or simply ‘dark.’ Other times in our Sourcebook[2], it is omitted from the translation, and all we are left with is ‘sea’ [pontos].

What does oinops mean? On the surface, oinops is a compound adjective that combines οἶνος [oinos, ‘wine’] and ὤψ [ōps, ‘eyes’ or ‘face’]. While ‘wine-dark’ has become a common translation for oinops in English, dark really isn’t part of the Greek word. In the video for Hour 24 Text C on HeroesX, Nagy and Muellner discuss this etymology, and suggest that we might think of the word as meaning ‘having the looks of wine’ – a similar translation is ‘wine-faced.’ So this is the literal meaning, but why are some things described as looking like wine?

As Jacqui stated in the introduction to this series, a number of us independently became interested in this phrase, and we began our word study together. This “word study” is modeled after the approach that Nagy took in H24H. Each Hour focused on the context of one or more keywords, and explored its context and related themes. To get to the significance of oinops to the ancient Greeks, we needed to look at the occurrences of the word in Greek poetry. But, unlike the scholars, the majority of us on the team know little to no Greek language. So how were we going to do this?

First Steps

The first step of our project was to become familiar with various online tools for Greek word study, many of which have articles introducing them elsewhere on Hour 25. For example, here is an article on Hour 25 about investigating Greek words: Investigating Greek Words; and video tutorials that introduce the Greek alphabet: The Greek Alphabet, with Joel Christensen and the Perseus Digital Library: Using Perseus Digital Library, with Anna Krohn. There are more tutorials under the “Learn” tab on this site: Greek Learning Modules .

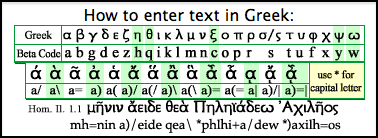

The Perseus website has a variety of powerful search tools (see below, most captions are hyperlinked), and the Word Study Tool is just one of them. You can access it via the Search Tools page at the Perseus website. You will find it on the far right of that page. Just above it is a key for entering Greek words into the tool. This is an important point: I have found it easiest to use the Perseus Word Study Tool when you have word you are interested in Greek letters (i.e., not transliterated). It is also useful to note that it is not necessary to enter the accents on the Greek vowels.

In this word study, we are interested in οἶνοψ [oinops]. To find this word, we can see from the key that we should not type “oinops” – doing so would yield no results because the Greek word does not end with pi + sigma, but rather psi. So we must type “oinoy” in the text field of the Word Study Tool because “y” is the symbol for ψ that Perseus uses.

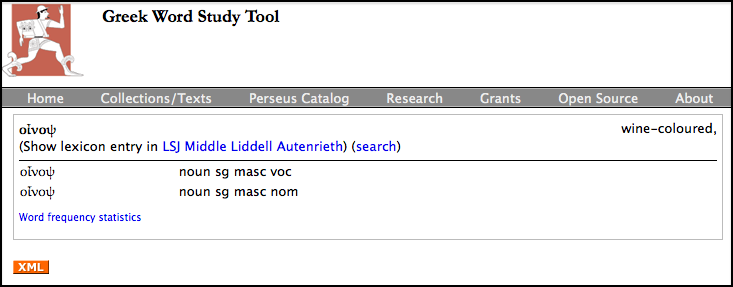

This is the result of a search for “oinoy” in Perseus:

This result shows us the lemma (dictionary form) entry for the word οἶνοψ with a brief definition as “wine-coloured.” There are a number of places to click on this page to access more information about the word of interest.

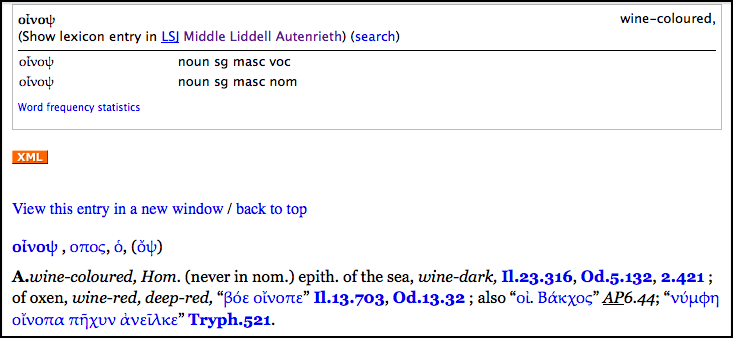

On the second line, there are multiple lexicon entries, including “LSJ,” which is a standard Greek-English lexicon[3]. Clicking on LSJ yields this:

Here we see more information about the context of the word, e.g. it is an epithet of the sea, and a few occurrences. Clicking on Il.23.316 would take you to the occurrence of oinops on line 316 of Iliad Scroll XXIII.

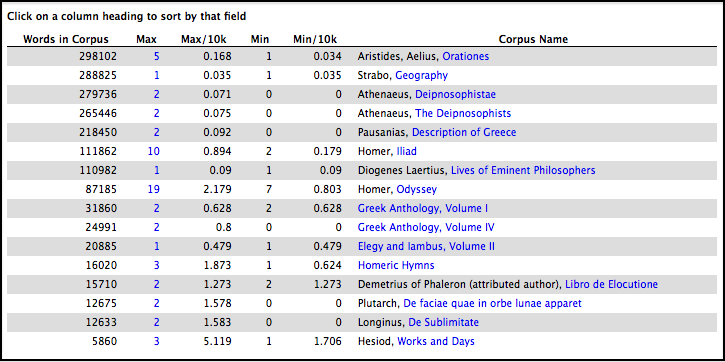

Near the bottom of the box that contains the results of the Perseus Word Study Tool search, there is another clickable link, “Word frequency statistics.” Clicking there brings up the following page:

The table above shows all of the occurrences of oinops in the texts archived on Perseus. The column labeled “Max” shows the maximum number of times that word is found in a particular work. It is clear that oinops is not a particularly common word, and it occurs most frequently in Homeric poetry.

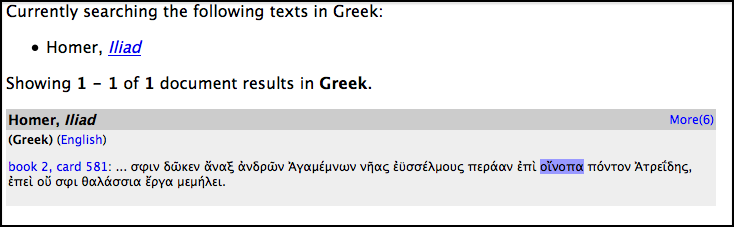

Since this was our first adventure in word study, we decided to tackle the Homeric epics first, with plans to expand to the Homeric Hymns and Hesiod. Clicking on the number “10” in the Max column for Iliad brings up this page:

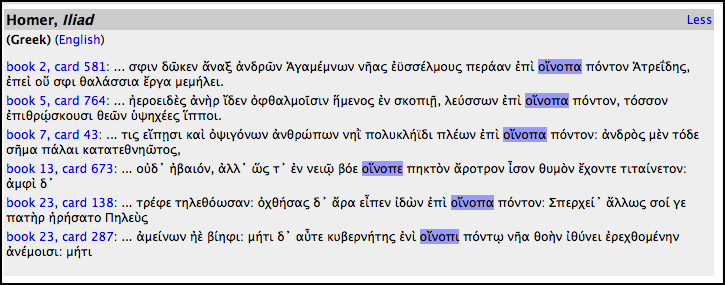

Clicking on “More(6)” will show all results from the Iliad.

The information presented here shows occurrences of oinops in the Greek text of the Iliad. Do not despair if you do not read ancient Greek! Simply click on one of the entries, for example “book 23, card 138” and you will see a new page:

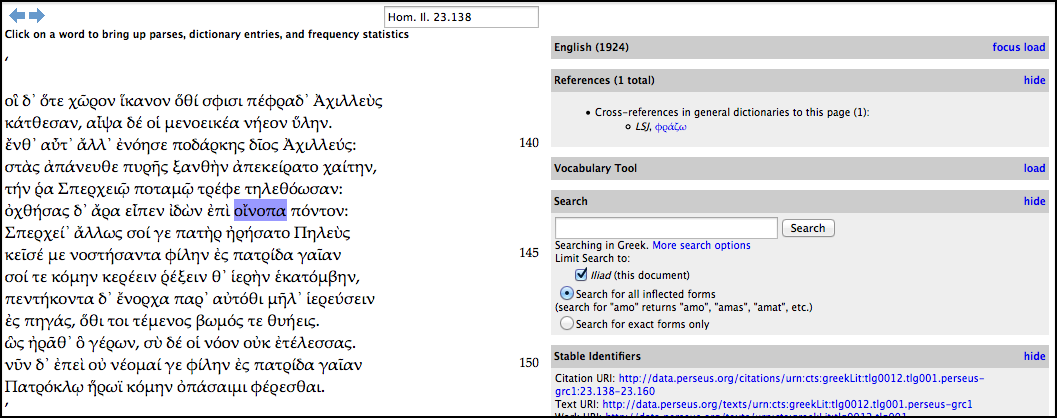

On the left is the Iliad in Greek, and you can see the occurrence of oinops (in a different form), highlighted in blue at line 143. Note that each Greek word is clickable – the link will open another page with a dictionary entry for that word (or sometimes more, depending on if that spelling is common to multiple words). To see an English translation side-by-side with the Greek, click on “load” in the line that says “English (1924)” (note that some entries have multiple English translations to pick from, including the Nagy-modified Butler from our Sourcebook). In this passage, mournful Achilles looks out over the oinopa ponton prior to the funeral of his fallen therapōn Patroklos.

Coming Together

We met via Google+ Hangout and decided to divide up the occurrences of oinops in the Iliad and Odyssey. This meant each person had two or three instances to research in each epic, which allowed time for “close reading” of the text surrounding each occurrence. We took note of where oinops occurred in the Greek passage (for example, at the end of a line, in the middle of a line), what noun the adjective modified, and what was the overall context of the usage. We compared multiple translations, including the ones in Perseus and our Sourcebook, and reported our findings in another Google+ Hangout. A favorite part of this project was participating in close reading together during these hangouts. Often times each one of us would be inspired to make connections and see patterns within the text based on others comments and insights. We kept a log of our studies in a set of shared documents on Google Drive.

We found that oinops appears 24 times in early Greek epic (Homeric epics, Homeric Hymns, and Hesiod), and was used to modify only two different nouns: πόντος [pontos, ‘sea’] and βοῦς [bous, ‘ox’]. How strange, we thought! What connects these two nouns with oinops? If we start with the literal translation of ‘wine-faced’ for oinops, why wine-faced sea and wine-faced oxen? Is there a deeper meaning? What do you think? Forum discussion starts now!

Coming next time: Connecting with Oinops

Download Oinops Passages here: Oinops Word Study Passages (PDF)

Notes

[1] Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor.

[3] LSJ: Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek-English Lexicon. revised and augmented throughout by. Sir Henry Stuart Jones. with the assistance of. Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940. Online at Perseus.

Image credit

Exekias Dionysos kylix, Dionysos in a ship, sailing among dolphins. Attic black-figure kylix, ca. 530 BC. From Vulci. Wikimedia Commons,