This latest exploration of Core Vocabulary terms from The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours[1] and the associated Sourcebook[2] is esthlos [ἐσθλός] “‘genuine, good, noble’; synonym of agathos.”

The first thing I noticed is that it is far less frequent than agathos.

In poetry I wondered if it was employed for metrical reasons (two syllables, starting with a long, as opposed to three syllables starting with two short) or whether there were any specific usages, in particular the sense of “genuine.” And how should the word best be translated in different contexts?

Here are a few examples to start the discussion.

Here are a few examples to start the discussion.

In Homeric epic we sometimes find this adjective (and others) used as a substantive, for example when Agamemnon rails at Kalkhas for suggesting he return the daughter of Khrysēs:

Seer [mantis] of evil, you never yet prophesied good things concerning me, but have always loved to foretell that which was evil. You have brought me neither comfort [esthlon] nor performance

Iliad 1.106–108[3]

For this passage Benner’s notes[4] suggest: “[108] ἐσθλόν = Attic “ἀγαθόν”, here in sense of ‘pleasant,’ ‘gratifying.’”

Theognis also has examples of the adjective as substantive, as, for example, in this passage, where he also uses agathos apparently as a synonym:

For you shall learn good (things) [esthla] from good (men) [esthloi]: but if you mingle with bad (men) [kakoi], you shall lose your existing noos. Having learnt this, consort with good (men) [agathoi], and some day you will say that I advised my friends [philoi] well.

Theognis 35–38[5]

Instead of simply translating as esthlos and agathos as “good” and kakos as “bad,” perhaps “noble” and “ignoble” respectively would work in this context: what do you think?

Penelope, in conversation with a dream version of her sister (sent by Athena), refers to her husband twice with the adjective esthlos within a couple of lines:

You are even ordering me to stop from misery and many mental-pains,

which provoke me through my mind [phrēn] and through my heart [thūmos],

(I) who before lost my noble [esthlos] lion-hearted husband,

who surpassed in all kinds of noble-goals [aretē] among the Danaans,

the noble-one [esthlos], whose glory [kleos] was broad through Hellas and middle ArgosOdyssey 4.812–816[6]

The word esthlos most frequently collocates[7] with kakos [κακός] “‘bad, evil, base, worthless, ignoble’” (Core Vocab), sometimes as a direct contrast (as we have already seen in the Theognis passage above).

Here, the Chorus has been telling Antossa about Athens which her son Xerxes has been attempting to attack:

I think that you will soon learn the truth of the matter. For here comes one who is beyond a doubt a Persian courier. He bears clear tidings of some issue, be it good [esthlon] or bad [kakon].

Aeschylus Persians 246–248, adapted from translation by Herbert Weir Smyth [8]

In this next passage, Diogenes Laertius is discussing Crantor, who quotes the poet Antagoras addressing Love (Eros):

And it is said that there are extant these lines of the poet Antagoras, spoken by Crantor on Love: My mind is in doubt, since thy birth is disputed, whether I am to call thee, Love, the first of the immortal gods, the eldest of all the children whom old Erebus and queenly Night brought to birth in the depths beneath wide Ocean; [27] or art thou the child of wise Cypris, or of Earth, or of the Winds? So many are the goods [esthla] and ills [kaka] thou devisest for men in thy wanderings. Therefore hast thou a body of double form.

Diogenes Laertius Lives of Eminent Philosophers 4.5.27, adapted from translation by R.D. Hicks[9]

Another frequent collocation is kleos [κλέος] “‘glory, fame (especially as conferred by poetry or song); that which is heard’” (Core Vocab). With kleos the combination is most frequent in epic, and is also found in the poetry of Pindar and Theocritus. Here are a some examples:

Good friend, truly the father of men and gods greatly honors your head and the bull-like Earth-Shaker also, [105] who keeps Thebe’s veil of walls and guards the city,—so great and strong is this fellow they bring into your hands that you may win great [esthlon] glory [kleos].

Hesiod Shield of Heracles 103–107, adapted from translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White[10]

Athena wishes for Telemachus to gain glory by traveling to Sparta and Pylos:

And I will conduct him to Sparta and to sandy Pylos, 94 and thus he will learn the return [nostos] of his dear [philos] father, if by chance he [= Telemachus] hears it, [95] and thus may genuine [esthlon] glory [kleos] possess him throughout humankind.”

Odyssey 1.93–95, from translation by Gregory Nagy[11]

Referring to the Patroklos in connection with the immortal horses which he used to drive for him, Achilles says:

you know how much my steeds are better in excellence [aretē] than all others—for they are immortal; Poseidon gave them to my father Peleus, who in his turn gave them to myself; but I shall hold aloof, I and my steeds [280] that have lost the genuine [esthlon] glory [kleos] of their kind driver, who many a time has washed them in clear water and anointed their manes with oil.

Iliad 23.276–282, adapted from Sourcebook[12]

Theocritus refers to the kleos as in terms of its being through poetry or song, being genuine or noble, compared to material wealth:

[115] But it is not for his wealth that the interpreters of the Muses sing praise of Ptolemy; rather is it for his well-doing. And what can be finer for a wealthy and prosperous [olbios] man than to earn a fair [esthlon] fame [kleos] among his fellow-men? This it is which endures even to the sons of Atreus, albeit all those ten thousand possessions that fell to them when they took Priam’s great house, they lie hid somewhere in that mist whence no return [nostos] can be evermore.

Theocritus Idylls 17.115–120, adapted from translation by J.M. Edmonds[13]

Although Edmonds translates esthlon as “fair,” perhaps “genuine” would suit the sense just as well here.

The formula also occurs in an anonymous epigram:

Not even when dying have you lost all your good [esthlon] fame [kleos] on the earth,

but still the splendid gifts of your life [psūkhē] all remain,

all you were endowed with and learnt, you, best of all [pan-aristos] in intelligence [mētis] by nature:

therefore you have gone to the island of the blessed [makares], Pytheas.Greek Anthology 7.690[14]

Other collocations with esthlos include anēr [ἀνήρ] “man,” hetaîros [ἑταῖρος] “companion,” patēr [πατήρ] “father,” and paîs [παῖς] “child, son.”

In Euripides Andromache the Nurse chastises Hermione:

Your husband will not, as you think, end his marriage to you, [870] won over by the insignificant words of a barbarian woman. For you are not his as a prisoner taken from Troy, but he has received you with a large dowry and you are the daughter of an important [esthlos] man [anēr] and come from a city [polis] of no ordinary prosperity.

Euripides Andromache 869–873, adapted from the translation by David Kovacs[15]

The poet Bacchylides also uses the term:

The finest thing is to be envied by many people as a noble [esthlos] man [anēr]. I know also the great power of wealth, [50] which makes even a useless man valuable. Why have I steered my song in its straight course so far off the road? Delight is appointed for mortals after victory.

Bacchylides Ode 10.47–53, adapted from translation by Diane Arnson Svarlien[16]

With hetaîros, “companion,” it occurs only in Homeric epic. Here, for example, Arēs (in the likeness of Akamas) is encouraging the Trojans to fight:

With hetaîros, “companion,” it occurs only in Homeric epic. Here, for example, Arēs (in the likeness of Akamas) is encouraging the Trojans to fight:

“…Aeneas the son of great-hearted Anchises has fallen, he whom we held in as high honor as radiant Hector himself. Help me, then, to rescue our brave [esthlos] comrade [hetaîros] from the stress of the fight.”

Iliad 5.467–469, adapted from Sourcebook[17]

However, we find esthlos used to describe patēr, “father,” also in later contexts, such as in tragedy. For example:

My lord, I have listened and I pity these for what has befallen them. Nobility overwhelmed by mischance—this I now see in its full. For these children, [235] born of a noble [esthlos] sire [patēr], are suffering undeserved misfortune.

Euripides Heracleidae 232–235, adapted from translation by David Kovacs[18]

And here, also in tragedy, we see it used with paîs, “child, son,” and also by implication for the father (although the word patēr doesn’t appear in the Greek!), when Rhesus greets Hector:

Brave [esthlos] son [paîs] of one as brave [esthlos], Hector, prince [turannos] of this land, hail! After many a long day I greet you. [390] I rejoice at your success, to see you camped hard on the towers of the enemy [ekhthroi]; I am here to help you raze their walls and fire their fleet of ships.

Euripides Rhesus 388–392, adapted from translation by E.P. Coleridge[19]

Coleridge chose to translate as “brave,” perhaps because he reads Rhesus as flattering Hector’s efforts in the fighting so far. In the context he also refers to Hector’s status, so would you choose to translate esthlos any differently?

Overall, though, the word seems to fall out of use—although I found a few examples in later prose, in many cases the author is quoting Homer!

Please join me in the forum to discuss how best to translate the word in these and other contexts, and to share any further passages you find or notice where esthlos is used.

Notes

[1] H24H: Nagy, Gregory. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA: 2013. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[2] Sourcebook: The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours Sourcebook of Original Greek Texts Translated into English, Gregory Nagy, General Editor. 2020-07-17. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

https://chs.harvard.edu/book/the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours-sourcebook/

[3] English text: Homeric Iliad, Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power. Rhapsody 1: 2019-07-31. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Online at Perseus.

[4] Benner, Allen Rogers, Selections from Homer’s Iliad, with an introduction, notes, a short Homeric grammar, and a vocabulary. Allen Rogers Benner. New York. Irvington Publishers, Inc. 1903. Online at Perseus.

[5] Greek text: Elegy and Iambus. with an English Translation by. J. M. Edmonds. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. 1. Theognis: Section 1, elegies, online at Perseus.

[6] Greek text: Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online at Perseus.

[7] Collocation search at Perseus under PhiloLogic Some words that collocate, for example anthrōpos [ἄνθρωπος] “man(kind),” mainly form examples with simple proximity that do not usually agree in case or number with the adjective.

[8] English and Greek texts: Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. 1. Persians. Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1926. Online at Perseus.

[9] English and Greek texts: Lives of Eminent Philosophers. Diogenes Laertius. R.D. Hicks. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1972 (First published 1925). Online at Perseus.

[10] English and Greek texts: Hesiod. The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White. Shield of Heracles. Cambridge, MA.,Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online at Perseus.

[11] English text: Homeric Odyssey. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power. 2019-07-31. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

Greek text: Homer. The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online at Perseus.

[12] English text: Homeric Iliad. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power. Rhapsody 23 2019-12-12. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Online at Perseus.

[13] English text: The Greek Bucolic Poets. Translated by Edmonds, J M. Loeb Classical Library Volume 28. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1912. Online at theoi.com.

Greek text: Idylls. Theocritus. R. J. Cholmeley, M.A. London. George Bell & Sons. 1901. Online at Perseus.

[14] Greek text: The Greek Anthology. with an English Translation by. W. R. Paton. London. William Heinemann Ltd. 1917. 2. Online at Perseus.

[15] English and Greek texts: Euripides, with an English translation by David Kovacs. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. forthcoming. Online at Perseus.

[16] English text: Bacchylides. Diane Arnson Svarlien. Odes. 1991. Online at Perseus.

Greek text: Bacchylides. The Poems and Fragments. Cambridge University Press. 1905. Online at Perseus.

[17] English text: Homeric Iliad. Translated by Samuel Butler. Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power. Rhapsody 5 2019-07-31. Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies.

Greek text: Homer. Homeri Opera in five volumes. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 1920. Online at Perseus.

[18] Greek and English text: Euripides. Euripides, with an English translation by David Kovacs. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. forthcoming. Online at Perseus.

[19] English text: Euripides. The Plays of Euripides, translated by E. P. Coleridge. Volume I. London. George Bell and Sons. 1891. Online at Perseus.

Greek text: Euripides. Euripidis Fabulae, vol. 3. Gilbert Murray. Oxford. Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1913. Online at Perseus.

Image credits

Detail of Kalkhas from Fresco of the sacrifice of Iphigeneia, from House of the Tragic Poet, Naples.

Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

A Persian soldier of the Achaemenid army. Detail of the tomb of Xerxes I, c 480 BCE

A Davey, Diego Delso: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic license, via Wikimedia Commons.

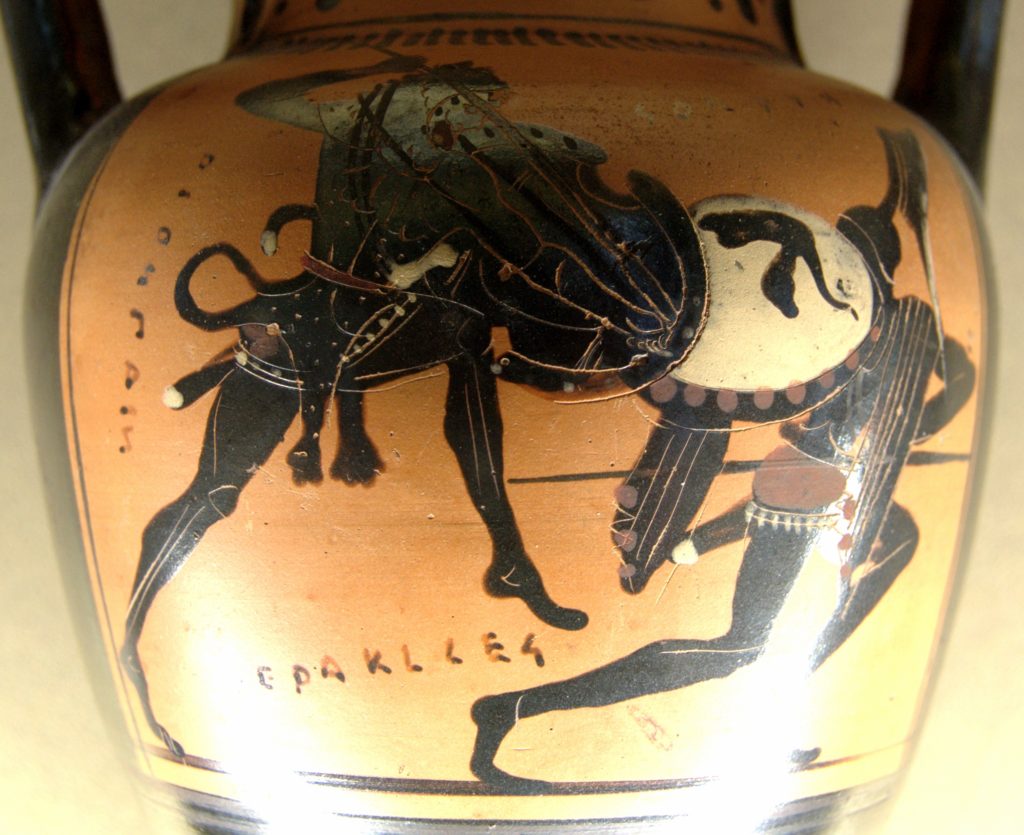

Diosphos Painter: Herakles and Kyknos, side A, Attic black-figured neck amphora. Louvre.

Bibi Saint-Pol, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Hermione, depicted on a coin

trlkly, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Young warrior, so-called Ares. Plaster replica of Roman copy of Greek original. Canope at Villa Adriana.

EricMachmer (derivative work) Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Note: Images have been selected from pictures that are freely available with open source or Creative Commons licenses or from photographs sent in by community members for the purpose. The images in this post are intended to suggest the subject, rather than illustrate exactly—as such, they may be from other periods, subjects, or cultures. Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Online texts and images accessed December 2020.

___

Sarah Scott has a degree in Language from the University of York, and has worked as an editor, technical author, and documentation manager. She is the Executive Producer for the HeroesX project, and one of the Executive Editors of the HeroesX Sourcebook. She is an active participant and member of the editorial team in Kosmos Society, with a particular interest in content development, document management, word studies, language learning, comparative linguistics, and digital humanities.