The year 2020 may not be the best time to travel with the pandemic. And yet, who does not want to discover the islands of the Aegean Sea? I offer you a safe and virtual journey through time to an island with many names and a tumultuous past.

The name by which this magical place is often mentioned in ancient Greek literature is Thera.

Pindar, who takes so many ancient myths at heart, in Pythian 4 and 5 reminds us of the history of the inhabitants of this island who lived there for a rather long period of time, ancestors of Pindar himself. And the island of sea-beaten Thera is described by him as a “metropolis of mighty cities”.

The Aegidae, he writes, coming from Sparta settled in Thera and remained there for 17 generations, not by choice but because of a decision by fate. Thus Pindar in Pythian 4[1] mentions the prophecy made by Medea at Thera as in his ode he is celebrating the victory of a descendant of Battos, Arkesilas IV, son of Battos IV, king of Kyrene.

…on a day when Apollo happened to be present, gave an oracle naming Battus as the colonizer of fruitful Libya, and telling how he would at once leave the holy island and found a city of fine chariots on a shining white breast of the earth, and carry out [10] in the seventeenth generation the word spoken at Thera by Medea, which once the inspired daughter of Aeetes, the queen of the Colchians, breathed forth from her immortal mouth. She spoke in this way to the heroes who sailed with the warrior Jason….

That token shall make [20] Thera the mother-city of great cities, the token which once, beside the out-flowing waters of lake Tritonis, Euphemus received as he descended from the prow, a clod of earth as a gift of friendship from a god in the likeness of a man…Pindar Pythian 4, translation by Diane Arnson Svarlien

In Pythian 5 Pindar celebrates the same victor as in Pythian 4, and he mentions that he shares the same ancestors from Thera[2].

But it is my part to sing of the lovely glory that comes from Sparta, where the Aegeidae were born, and from there [75] they went to Thera, my ancestors, not without the gods; they were led by a certain fate.

Pindar Pythian 5, translation by Diane Arnson Svarlien

Herodotus recounts in great detail the story of Thera, in Book 4.147–162. A man called Theras, from the line of Cadmus, was a regent in Sparta while his nephews were young, but when they became kings he went to Thera, as we call it now but at his time it was called Kallistē, “the most beautiful,” to join his family, the descendants of Membliaros left there by Cadmus. Then Theras sailed with three thirty-oared ships. And the island Kallistē changed its name to Thera after Theras. Herodotus goes on with the story of the children of the Aegidae at Thera and the different kings of Thera, Grinnos king of Thera, a descendant of Theras, and Battus, a descendant of Euphemos of the Minyan clan….

Herodotus[3] goes on with many digressions, as usual. Was Thera part of the trade routes? The island was inhabited by Phoenicians before the Spartans. Phoenicians and people from Crete, a murex fisherman, and a Samian ship sailing for Egypt are mentioned in the Theraeans’ quest about Libya, where they are ordered by an oracle to start a colony at Cyrene.

But Herodotus gives a confirmation of the change of name of the island:

As for the island Calliste, it was called Thera after its colonist.

Herodotus The Histories 4.148, translation by A,D Godley

Pausanias[4] adds that there was a hero cult in Thera in honor of Theras.

And Theras changed the name of the island, renaming it after himself, and even at the present day the people of Thera every year offer to him as their founder the sacrifices that are given to a hero.

Pausanias, Description of Greece 3.1.8. from A Pausanias Reader

Apollonius[5] gives a slightly different version in his resumé of the story:

[1755] Thus he spake; and Euphemus made not vain the answer of Aeson’s son; but, cheered by the prophecy, he cast the clod into the depths. Therefrom rose up an island, Calliste, sacred nurse of the sons of Euphemus, who in former days dwelt in Sintian Lemnos, and from Lemnos were driven forth by Tyrrhenians and came to Sparta as suppliants; and when they left Sparta, Theras, the goodly son of Autesion, brought them to the island Calliste, and from himself he gave it the name of Thera. But this befell after the days of Euphemus.

Apollonius, Argonautica, Book 4.1755–1764, translation by R.C. Seaton

However, none of these authors knew about the distant past of this volcanic island. There is no mention of the gigantic explosion of the volcano, but the fascinating Bettany Hughes in her book Helen of Troy presents a detailed account of what happened around 1600 BCE.

As so often, the discovery of the archaeological site of Thera was carried out following excavation work. By accident the workers while digging discovered the remains of what seemed like a Minoan/Mycenaean city dating back to pre-Homeric and pre-Classical times; the city that was thus revealed dated from the Aegean Bronze Age era.

The volcanic eruption was monstrous, and probably followed by a gigantic tsunami. Most of Thera Island exploded along with the volcano.

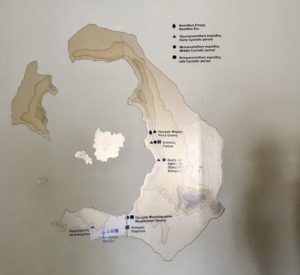

The map below shows what remains of the island, with, in the middle, small islands on each of which remains a volcano, the largest being the one that exploded around 3,600 years ago.

As Hughes states, “The Bronze Age World was brutalized.”

Since the excavations did not reveal any bodies, it is clear that the inhabitants had time to leave the island before the eruption.

Hughes was particularly interested in one fresco showing a woman saffron-gatherer, who, she thinks, could look like how Helen might be pictured (on the right in the image below).

Here is what Hughes[6] writes:

The women and girls who harvest the saffron crop are clearly the highest-born …these frescoes present detailed impressions of a Bronze Age princess. This is how Helen would (almost certainly) have looked had she walked through a Mycenaean citadel.

Hughes, B. 2006. Helen of Troy,

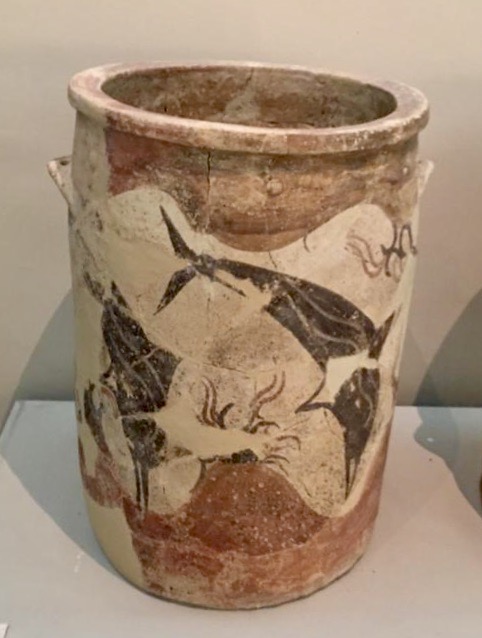

The following pictures show some of the artifacts found at the archaeological site.

This last jar shows some dolphins:

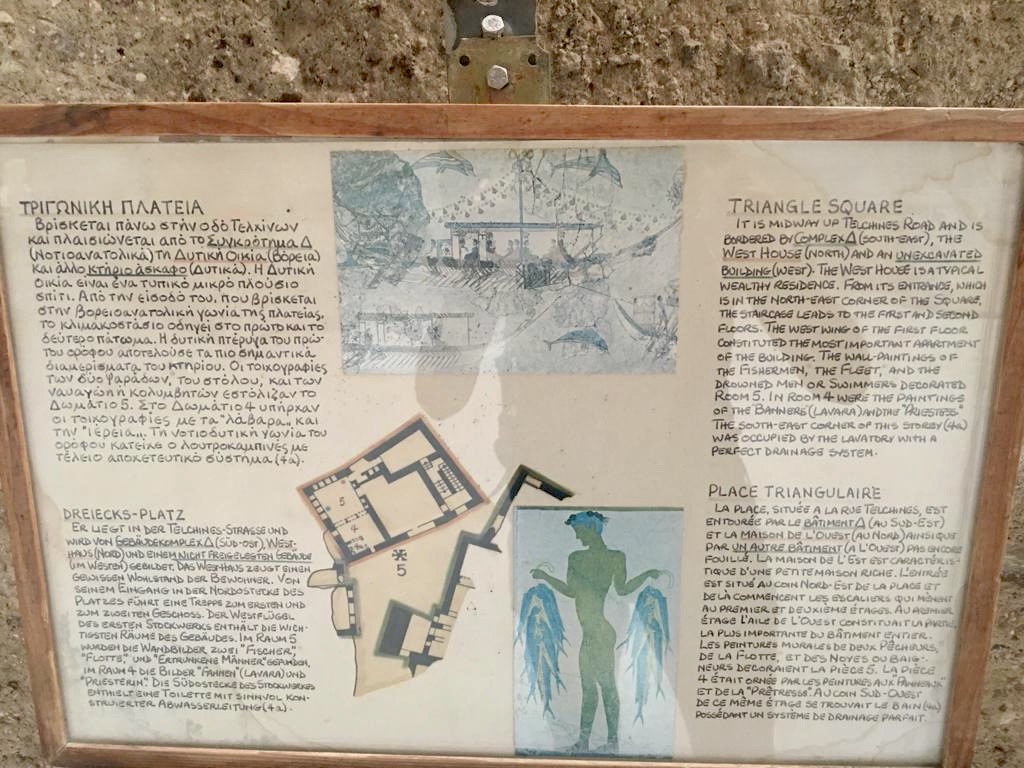

The excavations at Akrotiri, the place where there was a very complex and well developed city before the explosion, are a project of the Archaeological Society at Athens. This project was started in 1967 by Professor of Archaeology, Spyridon Marinatos, and is still in progress. The city had a dense network of streets. Many rooms were found with marvelous frescoes, others were storerooms, some pipes were also discovered, indicating the presence of an aqueduct that brought water from the foot of a mountain where there were fresh water springs. A complex drainage-sewerage system was also discovered.

Some tablets with Linear A writing were also found:

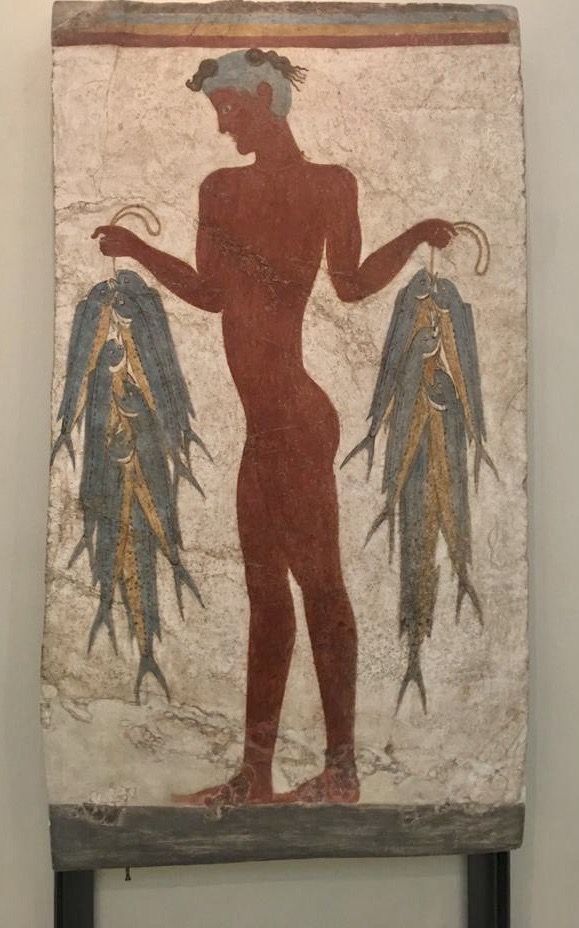

This amazing fresco of a young boy holding fishes is at the Museum in the small town of Fira, in Thera, at the Museum. We may deduce that they were eating fish during Bronze Age. There are few mentions of fish as food in Homeric poetry.

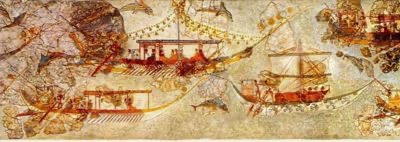

The fresco was found in what is called the “Triangle square” and in the same room the famous flotilla fresco was also there on the walls.

Nagy[7] in H24H, Hour 23, gives some insights of the meaning of the Fleet fresco found at Akrotiri.

The primary attestation comes from the evidence of pictures painted on the plastered surface of inner walls at the site of Akrotiri on the Aegean island of Santorini, the ancient name of which was Thera. This evidence can be dated back to the time when the prehistoric volcano that once occupied most of this island exploded, some time around the middle of the second millennium BCE, leaving behind a gigantic caldera that now occupies the space where the mountain once stood. The wall paintings to which I refer were preserved by the volcanic ash that buried the site of Akrotiri in the wake of the explosion. I concentrate here on a band of paintings that line the inner walls of “Room 5” in a building known to archaeologists as the West House – although there is currently no agreement about what exactly is meant by the term “house” in this instance. This band of paintings, known as the Miniature Frieze, has been described as “one of the most important monuments in Aegean art.” …

23§20. What we see painted on the wall of Room 4 shows the same garlanded frame of vision that we see painted in the Miniature Frieze decorating the south wall of Room 5. But there is a big difference. Whereas the man who is seated in the “cabin” positioned at the stern of the ship in the picture painted on the plaster wall of Room 5 can look through the garlanded frame of vision and see the sights to be seen as he sails ahead on his sea voyage, a viewer who looks at the plaster wall of Room 4 and sees a picture of the same garlanded frame of vision could merely imagine the sights to be seen in the course of such a sea voyage….

What is being represented in both paintings, I argue, is a prototype of a theōriā in the sense of a ‘sacred journey’ that leads to the achievement of a mystical vision. And that view of that vision is framed by the two semi-circular garlands through which the viewer views what is seen. To borrow from a modern idiom, the vision is viewed through rose-colored glasses.Nagy, Gregory 2013, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, Harvard

Below are pictures of the Flotilla and the garlands.

As we may read in Nagy’s passages above, Santorini is another name given to the island, so it is possible to trace a sequence from Kallistē to Thera and then to Santorini.

A fourth name for Thera, Strongili, is suggested by Eric Cline[8] in “Finding Atlantis?,” the ninth chapter of Three Stones Make a Wall, as he is looking at the possibility that Thera could be the “lost Atlantis”, if the myth holds some truth.

I, and many other archaeologists, suspect that if there is any kernel of truth underlying the myth of Atlantis at all, it is probably the volcanic Greek island of Thera, also called Santorini, which erupted during the middle of the second millennium BCE…

The name Santorini is rather recent—it was the Venetians who gave the island that name, after Saint Irene. An older name, frequently used by archaeologists, is Thera, which the Greek historian Herodotus says comes from the name of a Spartan commander named Theras, who was the leader of a colony established there during the first millennium BCE. Even before that, the island was called Kalliste, meaning the “beautiful one” or “fair one,” which Herodotus said was the name that the Phoenicians gave to the island (even though kalliste is a Greek word). Some suggest that the very first name of the island may have been Strongili, which translates as “the round one” and which makes sense, since it is circular in shape. It is actually a volcano and is still active today.

Chapter nine “Finding Atlantis?” from Eric H. Cline, Glynnis Fawkes, Three Stones Make a Wall, Princeton

The myth of Atlantis has been told by Plato[9] in two of his dialogues, Timaeus and Critias.

….the island of Atlantis, which we said was an island larger than Libya and Asia once upon a time, but now lies sunk by earthquakes and has created a barrier of impassable mud

Plato Critias 108, translation by W.R.M. Lamb

You may read the whole argument about the symbolism of a perfect city and perfect life in the Critias. The myth was reported to Plato through the words of Solon’s descendants, and Solon heard it from Egyptian priests.

Notes

[1] Odes. Pindar. Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

Pythian 4, online at Perseus

[2] Odes. Pindar. Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1990.

Pythian 5, online at Perseus

[3] Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920.

Online at Perseus

[4] Pausanias Description of Greece, Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. The translation is edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy. Available online at:

https://chs.harvard.edu/CHS/article/display/5896.description-of-greece-a-pausanias-reader#III

[5] Apollonius, Argonautica, Book 4.1755

Online at theoi.com

[6] Hughes, B. 2006. Helen of Troy, Epub ISBN 9781446419144, Pimlico.

[7] Nagy, Gregory, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, Harvard Press, 2013. Available online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013

[8] “Chapter nine Finding Atlantis?” from Cline, Eric H. and Glynnis Fawkes. 2018. Three Stones Make a Wall: The Story of Archaeology. Princeton University Press.

Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/64583

[9] Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925.

Online at Perseus

Image credits

Saffron gatherers fresco, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Akrotiri Thera ship as depicted on the fresco of the West House at Santorini. Details of some ships of the “Thera Flotilla Fresco”: Akrotiri Westhaus Schiffsfresko 16-9 03.jpg. Public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Remaining photographs, credit: Eva & Jane, Kosmos Media Library

Most of the pictures were taken in Thera at the archaeological site of Akrotiri, and at The Prehistoric Museum of Thera.

____

Hélène Emeriaud is a HeroesX Team member. She studied ancient Greek at school in France and for several years at the University of Minnesota. She holds a degree in Education from Montreal University, and a Master of Education from McGill University. She is an active participant and member of the Editorial Team in the Kosmos Society with a particular interest in ancient Greek and Latin language learning.