Aegina is a Greek island not far from Attica; it is well known for the Temple of Aphaia, situated on an elevated site.

On the island, there is also a city named Aegina, at the northwestern end of the island, with a famous little harbor. The temple of Apollo was the main sanctuary in the town of Aegina. The remains of the foundations are still there and only one upright column stands, named Aegina Colonna, at Cape Colonna, dated from around 500 BCE.[1]

Even before the archaic period, the Aeginetans were using boats to travel far and trade goods. At the small Archaeological Museum of Colonna, a splendid storage vessel dated from 1800–1650 BCE showing four amazing boats attests to the already important use of the sea for trade by the people of Aegina during the Mycenaean period.[2]

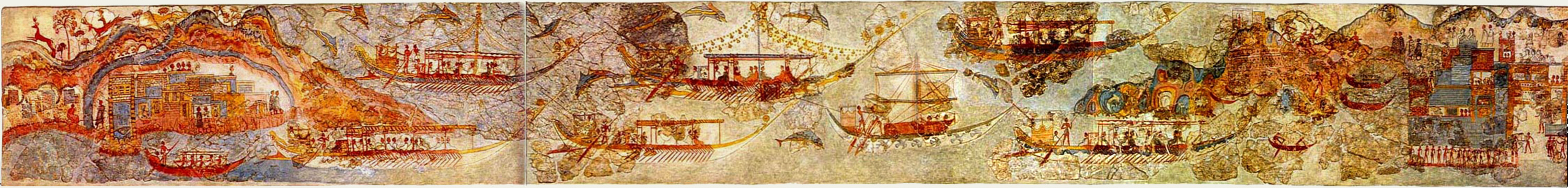

The painted scenes on this and other vases, dated early 2nd millennium BCE, betray the importance of the sea in the lives of the people of Aegina. Four ships in procession occupy the central zone of the vase that is represented in Figures 3 and 4. They are crescent-shaped with a curving stern bifurcation that compares to the ships represented in the Thera flotilla (shown in Figure 5), and on the Hagia Triada sarcophagus[3]. The decorations are framed by the usual geometric motifs. Are these near pharaoic river ships the prototype of the ancient Greek ship?

Around the middle of the 2nd millennium BCE, Aegina traded local products, using her own ships, to the Cyclades, Crete, and mainland Greece.

Strabo tells us that “Aegina was colonized successively by the Argives, the Cretans, the Epidaurians, and the Dorians”[4]

The island being poor, the people developed their sea power, built boats and became sea merchants. The island Aegina again developed itself to be an important trade center, exporting pottery and high-quality metalworking products, including bronze. By about 650 BCE, the Polis Aegina was the first city in the Greek motherland to facilitate trade by the use of coins. They were also the first to coin silver.[5]

Strabo writes also that:

...this is the island that was once actually mistress of the sea and disputed with the Athenians for the prize of valor in the sea fight at Salamis at the time of the Persian War… [6]

The people of the island were at first very close to Epidaurians, but at some point they had some conflict with the city and as described by Herodotus, they decided to build ships and to become independent from Epidaurus.

…at this time, as before it, the Aeginetans were in all matters still subject to the Epidaurians and even crossed to Epidaurus for the hearing of their own private lawsuits. From this time, however, they began to build ships, and stubbornly revolted from the Epidaurians. [7]

Aegina then became a maritime power [thalassokratia], and built boats.

Later on as shown by Herodotus:

This was the beginning of the Aeginetans’ long-standing debt of enmity against the Athenians…. [8]

The Aeginetans stole some sacred images of the goddesses Damia and Auxesia. Damia and Auxesia were two goddesses of human and agricultural fertility who belonged to the sphere of women. The images belonged to the Epidaurians. Indeed, the people from Epidaurus, having problems with their crops, had obtained authorization from Athenians to use some olive trees, which were sacred trees, since there were none yet in Epidaurus, and they made images of the two goddesses with these trees. Their land was fertile after that; therefore they had an agreement with the Athenians about the images. When the people from Aegina stole the sacred images from them, the people of Epidaurus stopped the agreement, and told the Athenians to deal with Aeginetans who had robbed the images. The Athenians tried to get the images back but it ended badly for them. After that failed attempt, the Aeginetans decided that nothing Attic should be brought to Aegina. [9]

In A Local History of Greek Polytheism Gods, People, and the Land of Aigina, 800–400 BCE, Irene Polinskaya explores the possibility of Auxesia and Aegina being not only deities of agricultural fertility, but also of human fertility: kneeling statues seem to indicate a birthing position. [10]

It is interesting to note that Pausanias says that he himself saw these images, many centuries later.[11]

As for the date for the beginning of the war or for the events which are at its source, it is difficult to find exactly. Douglas Frame at the end of his book Hippota Nestor has a note about it.

The date of Athens’ war with Aegina, which followed these events (Herodotus 5.85–88), has not been established. How and Wells 1928 on Herodotus 5.86.4 date the war to the time of Solon, perhaps 590–570 BC, citing Solon’s substitution of the Euboic for the Aeginetan standard in coinage and his prohibition of the export of grain; the Aeginetan embargo on Attic pottery (Herodotus 5.88.2) is also noted. But earlier dates for the war are generally preferred: the early seventh century (Dunbabin 1936/1937; Bradeen 1947:239), or even mid-eighth century (Coldstream 1968:361n10 and 2003:135). The context of the earlier part of the story involving only Athens and Epidaurus may have been the Calaurian Amphictyony of which both cities were said to be members (How and Wells on Herodotus 5.82.3)…. Lenschau 1944:227–228 believes that a Mycenaean origin is probable; Harland 1925 likewise proposes an early foundation of the league, noting (164n6) that late Helladic remains have been found at the sanctuary of Poseidon on Calauria, the cult center of the amphictyony. Harland 1925:162 imagines that the league had its highpoint in the eighth century and declined thereafter. [12]

Were there other reasons than the theft of the sacred images for the enmity between Aegina and Athens?

The Aeginetans who were the first Greeks to coin silver, a sign that they were active traders, used the turtle as an emblem for their coins

As noticed by Polinskya about the turtle:

Of the sea creatures, it was rather sea turtles that were chosen as a symbol of the island, as they appear on Archaic Aiginetan coins and give them their characteristic name [13]

The coins with this motif (an animal sacred to Aphrodite), spread out over a large part of the Mediterranean, with Aeginetan ships reaching Egypt[14] and the Black Sea.

Herodotus stresses the presence of an Aeginetan fleet in Egypt by noticing that they were allowed to have a sanctuary to honor their gods in Egypt.

Amasis became a philhellene, and besides other services which he did for some of the Greeks, he gave those who came to Egypt the city of Naucratis to live in; and to those who travelled to the country without wanting to settle there, he gave lands where they might set up altars and make holy places for their gods.[15]

Herodotus mentions Sosastros, a particularly wealthy[16] Aeginetan trader who operated in the sixth century. Sosastros had close connections with Etruria, modern Toscana (Tuscany). He may have once dedicated a marble anchor found in Etruscan Tarquinia to the “Apollo of Aegina”[17]. In Etruria, numerous pieces of Attic pottery from the second half of the sixth century, were found with the signature SO. Probably they were the commodity of Sostratos.

The Athenian strategos Themistoklẽs persuaded the Athenians to build two hundred ships[20] for the war with non-democratic Aegina. In 480, the year of the Battle of Salamis, the Aeginetans balanced their interests and sided with the Athenians in their fight against the Persian domination. With their experience at sea, and their contribution of 40 ships, they contributed significantly to the Greek victory over the Persians. Herodotus 8.64 tells of the images of the Aiakidai being sent for in a naval [naustoleîn] mission from Aegina, before the battle. The sacred images would protect as well as be protected.

In these videos from The Ancient Greek Hero, Gregory Nagy and Leonard Muellner discuss Pindar Pythian 8.95–100 which relates to Aegina.

After the victory at Salamis the relations between Aegina and Athens firstly improved. Doric Aegina was an ally of Sparta and Athens conducted a pro-Spartan policy under Kimon. About 20 years later the alliance between the rivals failed. Athens wanted to put an end to the economic competition of Aegina, and attacked around 460 BCE, forcing it to surrender around 458 BCE. Athens demanded a large tribute from Aegina and forced the island to join the Delian League.[21] To complete the humiliation, the image of the sea turtle, which graced the Aeginetans’ coins, was maybe replaced by that of a land turtle, a tortoise. This symbolically might have indicated the end that had come to the naval power of Aegina.

Notes

[1] Date shown at the site.

[2] Based on information displayed at the site.

[3] “Ahhotep’s Silver Ship Model: The Minoan Context.” Shelley Wachsmann, Institute of Nautical Archaeology, Texas A&M University. Journal of Ancient Egyptian Interconnections.

[4] Strabo 8.6.16

[5] Strabo 8.6.16

[6] Strabo 8.6.16

[7] Herodotus 5.83.1

[8] Herodotus 5.82.1

[9] Summarized from Herodotus 5.82–89

[10] Polinskaya, Irene. A Local History of Greek Polytheism Gods, People, and the Land of Aigina, 800–400 BCE, chapter 7

[11] Pausanias 2.30.4

[12] Douglas Frame. 2009. Hippota Nestor Endnotes, part 3

[13] Polinskaya, Irene. 2013. A Local History of Greek Polytheism Gods, People, and the Land of Aigina, 800–400 BCE, chapter 7. Brill.

[14] For example, Aeginetan coins were found in Egypt, as listed in https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/hoards-and-overstrikes/

[15] Herodotus 2.178.1–3

[16] “Now this [= Tartessus] was at that time an untapped market; hence, the Samians, of all the Greeks whom we know with certainty, brought back from it the greatest profit on their wares except Sostratus of Aegina, son of Laodamas; no one could compete with him.” Herodotus 4.152.3

[17] Nancy Thomson de Grummond; Erika Simon. 2006. The Religion of the Etruscans. University of Texas Press. pp. 61ff.

[18] The emphasis on the depictions of ships on Attic kraters during this period may relate to Athenian naval campaigns against Aegina and other contemporary adversaries in the Aegean.

[19] “That island state, more predominantly maritime in its interests than Athens, seems to have kept an establishment of sixty galleys to Athens’ fifty, and in the recent hostilities Aeginetans had harried the Attic coast.” Burn, A.R. The Pelican History of Greece page 166

[20] Herodotus, Histories, 7.144.2

[21] “[1] The battle was fought at Tanagra in Boeotia, and the Lacedaemonians and their allies, after great slaughter on both sides, gained the victory. …. [4] Soon afterwards the Aeginetans came to terms with the Athenians, dismantling their walls, surrendering their ships, and agreeing to pay tribute for the future.” Thucydides The Peloponnesian War 1.108

Bibliography

Burn, A.R. 1966. The Pelican History of Greece. Penguin. Harmondsworth.

de Grummond, Nancy Thomson & Simon, Erika 2006. The Religion of the Etruscans. University of Texas Press. Available online at

http://www.academia.edu/15279416/THE_RELIGION_OF_THE_ETRUSCANS_Nancy_Thomson_de_Grummond_and_Erika_Simon_2006_

Frame, Douglas. 2009. Hippota Nestor. Hellenic Studies Series 37. Washington, DC: Center for Hellenic Studies

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Frame.Hippota_Nestor.2009

Herodotus Histories. Herodotus, with an English translation by A. D. Godley. Cambridge. Harvard University Press. 1920.

Available online at Perseus

Homeric Odyssey, Translated by Samuel Butler, Revised by Soo-Young Kim, Kelly McCray, Gregory Nagy, and Timothy Power.

Online at the Center for Hellenic Studies

Pausanias A Description of Greece. Translation based on the original rendering by W. H. S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes of Jones. Edited, with revisions, by Gregory Nagy. Online at CHS:

https://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.prim-src:A_Pausanias_Reader_in_Progress.2018-

Polinskaya, Irene. 2013. A Local History of Greek Polytheism: Gods, People and the Land of Aigina, 800-400 BCE. Leiden, Boston. Brill.

Strabo Geography. Strabo. Jones, H. L. (ed). 1924. The Geography of Strabo. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass.; William Heinemann, Ltd. London.

Online at Perseus

Thucydides The Peloponnesian War. Jowett, Benjamin. 1881. Thucydides translated into English, Volume 1. Clarendon Press. Oxford.

Online at Perseus

Image Credits

Figures 1–4: Kosmos Society image library

Figure 5: pano by smial [Public domain], Fresco of a ship procession from bronze age excavation at Akrotiri, on the greece island Santorini, Part 2 via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 6: Silver stater Aegina 485-480 BC. Obv. sea-turtle with single row of dots. Rev. incuse square with five sections. Pergamonmuseum. Berlin. O Mustafin (photo). Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 7: Boats cup, detail of the interior showing a frieze of five boats in contest. Attic black-figured cup, ca. 520 BCE. From Cerveteri. Leagros Group. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Photographer: Bibi Saint-Pol, own work, 2007-05-31. Public domain. From Wikimedia Commons

Figure 8: Drachm, Aegina, after 404 BCE. Land tortoise, head turned, seen from above. Inscription Α Ι Γ, dolphin in angles. BMC Attica: 193. SNG Copenhagen 524. Source = http://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=30243 Creative Commons CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

Attributions are based where possible by those shown by museums, or on Wikimedia Commons, at the time of publication on this website.

Websites accessed November 2018.

____

Rien, and Hélène Emeriaud, are members of the Kosmos Society.